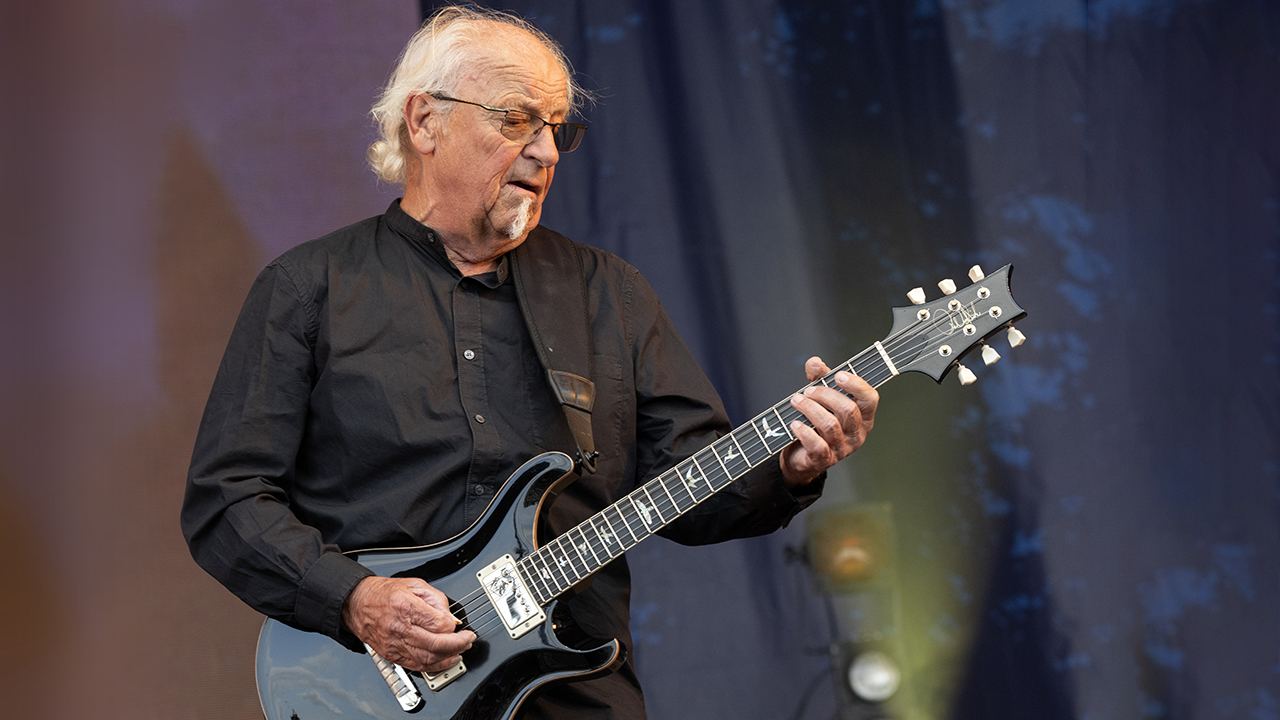

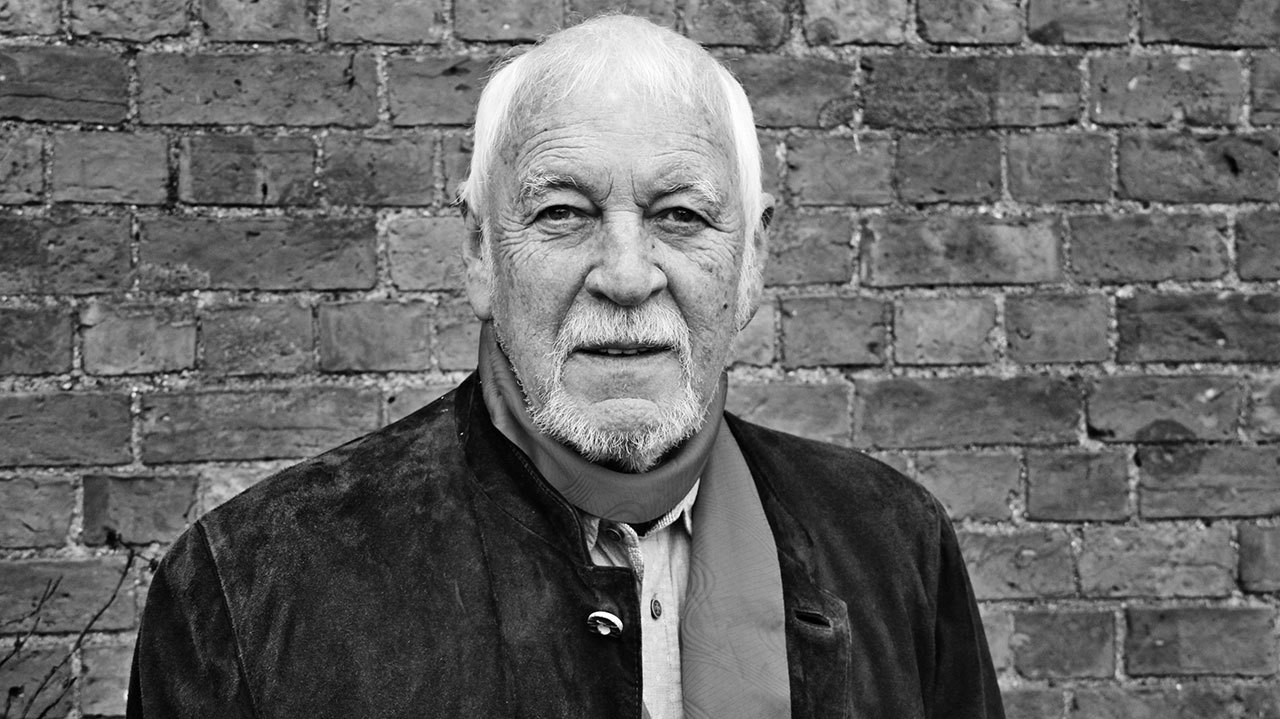

Gary Brooker on 50 years of Procol Harum

The Procol Harum singer/pianist on lyricists, banging his head and losing his hearing, and falling off logs in Finland

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

It might feel as if Procol Harum are emerging from an extended break – it has been 14 years since their last studio album, after all. But, as Gary Brooker is quick to point out, if that is the case, then what are they doing on tour every year? He does admit, however, that the band’s itinerary has included just three British shows in the past decade. Still, in the meantime there’s been a steady flow of live souvenir albums and DVDs, several of them featuring an orchestra in an attempt to emulate the band’s landmark Live With The Edmonton Symphony Orchestra back in 1971.

Now, with a new album, Novum, to coincide with the 50th anniversary of their debut it’s all hands on deck – although Brooker, whose dry wit camouflages an even deeper sense of British reserve, concedes that he was not exactly leading the charge from below deck.

“Obviously there’d been a lot of talk about the fiftieth anniversary from people like promoters, agents and the record company,” says Brooker. “And they were all waiting for me to say something. And I was looking for some kind of inspiration. That came when I went into the studio to start working on some songs, and realised how much I liked the process of making an album.”

Article continues belowThe biggest surprise about the album is that lyricist Keith Reid, who has been with you right from the beginning of Procol Harum, isn’t involved. What happened?

At some point after the last album we came to a crossroads; he turned left and I went straight on. There’s not a lot more I can say about it than that.

That must have been a tough blow, after such a long and successful partnership.

Not tough so much. I would say that it was extremely disappointing that we haven’t seen this thing through to our dying day. Whether he didn’t want to or didn’t see the point or whatever, it was just extremely disappointing

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Keith also seemed to be an integral part of the band. He was often on tour with you, sharing the whole group experience

He was, yes. But there are so many questions in the aftermath – like why was he there? Moral support, maybe. But there’s always people who do that.

(After a short silence) So you needed to find another lyricist?

We needed words, certainly. I mean, I have worked on albums myself and I’ve worked with other lyricists, such as Pete Sinfield. I knew Pete Brown and he knows my producer. I’ve always liked his writing. We talked about it and he seemed keen. As a person he was able to throw himself into making a set of songs.

According to Pete, you used to sing Keith’s lyrics without making any changes, whereas Pete was happy to come into the studio and change the lyrics if they didn’t fit the music.

That’s correct. Pete was far more adaptable. He told us in advance that he would be coming to the studio so that he could solve any problems that might arise. And that’s just what happened. As much as you might think you know what I like singing, it’s not that easy. It’s not just about the content. It’s also the phrasing. Sometimes it’s only when you sing it that you find there’s a problem, particularly if you’re trying something different, which is what I like to do, not just the obvious.

There were a couple of times when I was singing something in the studio and it was sounding awkward however hard I tried. I just couldn’t get around it. And we had to discover whether it was just the word, or whether the phrase just didn’t fit. And he’d say: “Okay, I’ll rewrite it.” But in order for him to do that he had to know what I can sing.

Did Pete’s words open you up to trying new things vocally as well?

Oh, I think I’ve sung quite a lot of things on here that I’ve never sung before. Particularly some of the tones. It was very refreshing. Some of that was also down to the lads in the band as well, the way they were playing on the day.

Was the album recorded in the traditional manner,with everybody playing together in the studio?

It was. It seemed natural to us to do it that way. And our producer, Dennis Weinreich, definitely wanted to get that live vibe in the studio. There’s also that particular way you play songs that you’ve just written but are not fully familiar with yet.

It was a fairly straightforward album to make. It was a question of let’s make a new album, write some songs, us boys. I mean, we are Procol Harum, whatever that may be. Luckily that gives us fairly wide boundaries. We have our style but we are not constrained.

But the combination of grand piano and Hammond organ is surely an essential ingredient of that style.

Yes, I guess if there was no piano or electronic keyboard it wouldn’t sound so Procolly.

It also sounds like it was an enjoyable album to make, judging by the laughter that’s been left in at the end of the track called Neighbours.

Yes, and because it was after I’d finished singing that song it was absolutely real. But what wasn’t there was a gun – a starting pistol, actually – that I had in the studio that I fired right at the end of the song, which finishes quite abruptly. Nobody knew I had it. I was singing about my neighbour, who I hate. I really wish him ill. So I fired this pistol, right next to the microphone, and then I started to laugh because it sounded like a cap gun going off. It didn’t record very well either. So that got taken out.

The album sleeve by Julia Brown includes several elements from Procol’s first album cover. Was that your idea?

It certainly wasn’t. In fact it’s been a bit of a bone of contention. [He glares at his manager who is sitting at the next table, tapping away on his laptop.] There’s been a few discussions. I mean, I can see what Julia is doing. The girl looks a little more wispy but she’s surrounded by a little more comfort and luxury. Anyway, we move on. I expect I’ll get a free T-shirt of it and then I may change my mind.

That debut album caused some controversy at the time because it didn’t include A Whiter Shade Of Pale or your second single, Homburg.

Exactly. We didn’t want to give people something they’d already bought. Instead it had all the other songs that we’d written. But the record company didn’t see it that way.

We also made things worse for ourselves by throwing out the guitarist and drummer just three weeks after Whiter Shade Of Pale had been number one. We got a lot of flak for that.

Was that when Robin Trower and BJ Wilson joined from your previous band The Paramounts?

Yes. And that made it look as if The Paramounts had just morphed into Procol Harum, which was not the case at all. The Paramounts had disbanded as a group, and I went off and met Keith Reid and we started writing songs together. And that’s how Procol Harum got started. I had become a new person, really. I’d never written any songs in The Paramounts apart from a couple of B-sides. When we needed a new guitarist and drummer I got in touch with Robin and BJ and put their names on the audition list. But I’m not sure anyone else turned up.

In 2012, you fractured your skull while on tour in South Africa. What happened?

We were out there touring with 10cc and the Moody Blues – a very late British invasion, if you like. Except that we never got to play. We arrived in Cape Town, and it was my birthday so we went out and had a meal and a couple of beers. On the way back I was talking to a couple of locals, and that was the last thing I remember. Apparently I got doped with Rohypnol. I woke up with no memory of anything. I was taken to hospital for a scan and they found my brain was swollen.

So you were mugged?

Yeah, that’s basically what it was . I’m not sure if I was hit on the head or whether I just fell and hit my head. [The manager looks up from his laptop and interrupts: “You fell. Your wife was trying to carry you back to your room because you were passing out.”] Oh, I didn’t know that. I remember asking the doctor if I’d been hit and he said no. But I thought he was just trying to protect the South African tourist industry. I mean, Procol Harum getting mugged wasn’t good for business.

But you were back on tour again just five weeks later.

No way. I don’t think I did anything for at least three months. I stayed in South Africa for three weeks afterwards while they kept me under observation. At one point they thought they might have to drill into my skull to relieve the pressure.

But no lasting side effects?

Unfortunately I lost my hearing in my left ear, as well as my sense of taste and smell. And they haven’t come back. [The manager interrupts again to confirm that Procol Harum were indeed back on tour in Scandinavia just five weeks after the accident.] Was it as quick as that? I remember that trip because I was under guard. I kept falling down because I was having dizzy spells. I would be lying in bed and thinking that I was falling. That’s a horrible feeling. Actually, about two years earlier I’d injured myself falling off a pile of logs in Finland.

What were you doing on top of a pile of logs?

I was trying to get a photo. The coach had stopped in the middle of nowhere for us to have a pee. There was the Spencer Davis Group and The Animals as well as Procol Harum… I thought: “I must get this on camera.” But I fell off this pile of logs that I clambered up, and hit a sharp rock when I landed. It could have killed me if I’d landed on my spine or head. I survived, but it didn’t half hurt.

Just a week after this interview, Brooker had another fall, this time at London’s Royal Festival Hall when he missed a step and tumbled from the stage while walking off at the interval. He returned after an extended break, saying he had “a broken hand and a broken head”. The band’s touring schedule has been unaffected by the incident.

Novum is available now via Eagle Records. Procol Harum’s 50th-anniversary tour runs through Europe until October.

Procol Harum - Novum album review

Procol Harum: "We've been going 50 years, it's time to make some effort"

Hugh Fielder has been writing about music for 50 years. Actually 61 if you include the essay he wrote about the Rolling Stones in exchange for taking time off school to see them at the Ipswich Gaumont in 1964. He was news editor of Sounds magazine from 1975 to 1992 and editor of Tower Records Top magazine from 1992 to 2001. Since then he has been freelance. He has interviewed the great, the good and the not so good and written books about some of them. His favourite possession is a piece of columnar basalt he brought back from Iceland.