Chicago: prog, jazz rock or AOR? The truth was a mix of all three!

We chart the development of Chicago, from jazz-flecked prog rockers to multi-million selling hitmakers

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

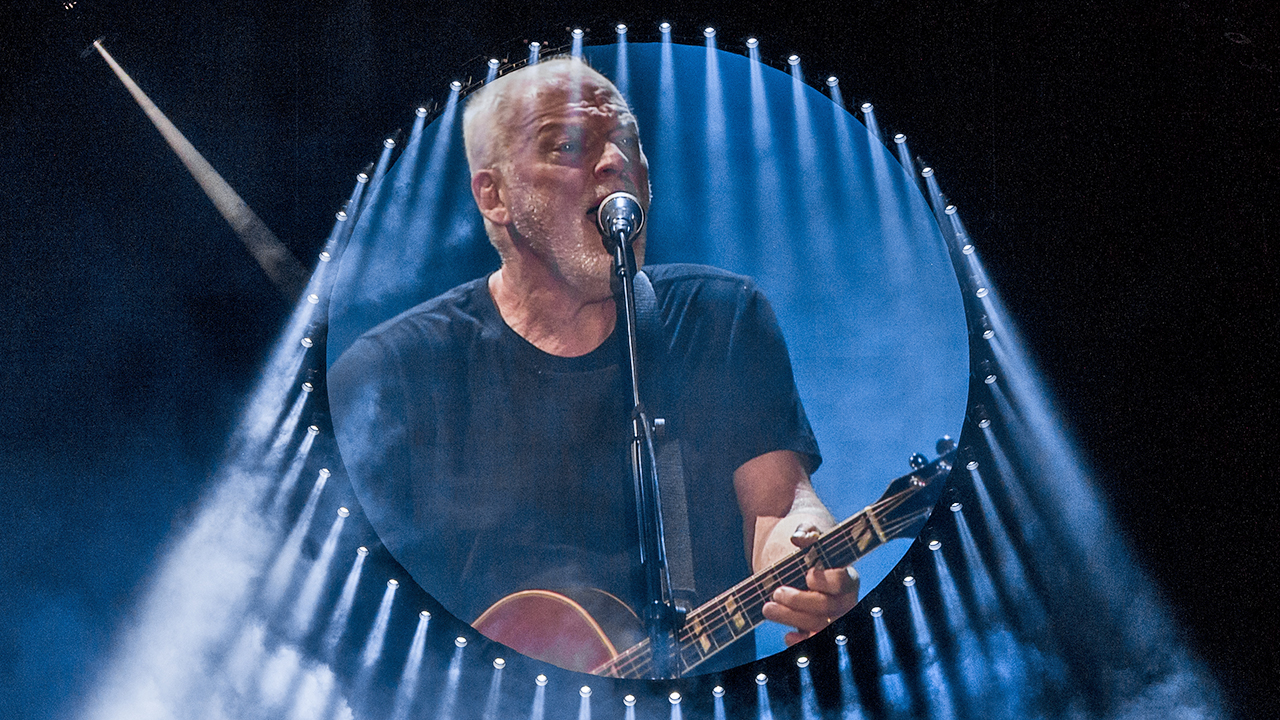

Robert Lamm has no doubts at all about Chicago’s musical pedigree. “We are a progressive rock band, and always have been,” he says confidently. “There’s nothing I like more than going into a record store and finding our back catalogue filed in the prog section, alongside greats such as Yes and Genesis.”

The keyboard player/vocalist, who co-founded the band in 1967 under the name The Big Thing, dismisses the notion that Chicago should be defined by a string of soft rock hits like If You Leave Me Now and Hard Habit To Break.

“They are part of our repertoire, but to suggest this defines what Chicago are all about is like claiming that Owner Of A Lonely Heart is the real Yes, or that Land Of Confusion tells you everything about Genesis. We have always felt blessed enough to try anything at any time. There’s a freedom to our music that probably comes from the era in which we started. Never in our career have we been pressurised to do something in a certain way.”

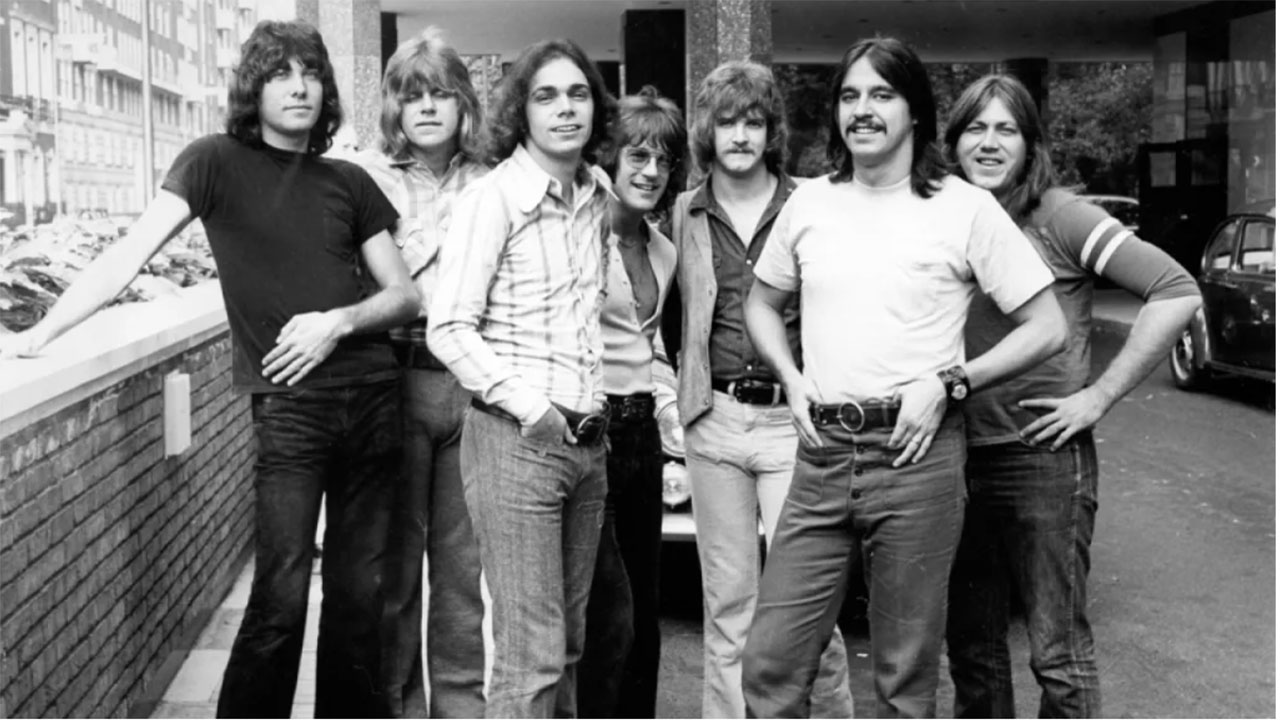

The band members all met at university in the Illinois area and started off as a covers act. Back then, they performed the Top 40 hits of the era but were never content to just mimic the originals. Instead, they would create their own extended arrangements, which would stretch them as musicians. Eventually, this inspired them to start thinking about how they might write their own material.

“Chicago always take me back to what I recall as the sunshine ’70s,” says Mostly Autumn guitarist Bryan Josh. “I remember first being aware of them when I heard the song If You Leave Me Now. That would have been around 1976. To me, the sound the band had was so unique, and even now it’s most definitely timeless. The fact they could be as accepted for their prog tracks as for the mainstream hits says a lot for their ability to be convincing on so many levels.”

In 1968, they became the Chicago Transit Authority and, having moved to Los Angeles, signed to Columbia.

“Our manager, James William Guercio, persuaded the label to sign us,” remembers Lamm. “He was very much our Svengali, and was also the band’s producer. He acted as the buffer between us as musicians and the record company so we never had to worry about the business end of things. All we had to do was write and record. We were artists. And somehow, Guercio got Columbia to agree to release our debut album [1969’s Chicago Transit Authority] as a double, which was almost unheard of for any artist making their first album at the time!”

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

The record was a Top 20 success, going on to sell more than a million copies, setting the pattern for a career that has seen the band surpass the 100 million sales mark.

“We were fortunate that the first record captured the integrity and potential of a young band who were all about celebrating our talent. We had never had any aspirations to be rock stars. What we wanted to do was show off every aspect of what we could do as artists. We never held back on anything. The aim was always to express ourselves.”

The band underwent another name change when the real Chicago Transit Authority legally objected, so they became Chicago just in time for the release of Chicago II in 1970. Another double album, this took them into the Top 5 in the US and made Number Six in the UK, cementing the band’s reputation as one of the most impressive young names on the scene. And as their success grew, so they were strongly drawn not to the more mainstream areas of music, but to those artists who were emerging from the British prog scene.

“We felt connected to the likes of Yes, Genesis and King Crimson. But I have to concede, we were also intimidated by them, because what they were doing was far beyond anything we could imagine. But we were also somewhat inspired by Yes and Crimson. They gave us a template from which to start and it’s because of their influence to some extent that we became confident about writing and recording very lengthy tracks.”

An interest in state-of-the-art studio technology also gave the band the opportunity to enhance their sounds to their maximum potential. However, Lamm is also aware that the band occasionally teetered on the edge of becoming self-indulgent, and this was brought into sharp focus in 1974 with the release of the chart‑topping Chicago VII.

“We’d gotten heavily into jazz by this time,” he admits. “And, if anything, we had too much musical freedom to play with. We were in serious danger of being pretentious, although thankfully it never got that far. But what we ended up with was another double album, with a combination of jazz pieces and also more commercial material. I suppose you could say that songs like If You Leave Me Now [which was a Number One hit for Chicago in 1976, on both sides of the Atlantic] was an antidote to the more experimental musical ambitions we had.”

The band were almost derailed in 1978 when guitarist Terry Kath died from a self-inflicted gunshot wound – it was accidental, and there was never any question of suicide. The timing couldn’t have been more significant because it happened just a short while after Chicago split with Guercio. These changes marked the start of what was to become their most successful period.

“We embraced the times, but we always did it in a way that never compromised what Chicago had always stood for. Essentially, we remained a prog rock band at heart, but what the soft rock hits did in the ’80s was allow us to carry on pushing the envelope on our albums. So, we might have had a big hit with something like You’re The Inspiration in 1984 [Number Three in the States and Number 14 in Britain], but if you listen to the album it comes from, Chicago 17, what you’ll hear is more challenging music. We weren’t just going for FM radio or MTV popularity, but like Genesis and Yes, we understood that if we gave the record company a hit single or two, then they’d leave us alone to be more creative on the rest of the album. It’s a policy that has served us well down the years and the eclectic nature of Chicago has been left intact.”

Just how determined the band have always been to resist imposed record label demands came to light when they made Stone Of Sisyphus in 1993.

“We recorded this on our own terms for Warner Brothers,” recalls Lamm. “Peter Wolf, our producer, encouraged us to be as adventurous and daring as we wanted. The idea was to forget entirely about trying to go for radio airplay and get fully back in touch with our progressive roots.

“When we finished it, the initial response from the label was positive. But then they changed their minds and wouldn’t release the album as it stood. We wouldn’t change anything on the record, so it was shelved.”

Although a few tracks did eventually emerge, it wasn’t until 2008 that the full album finally came out, under the title Chicago XXXII: Stone Of Sisyphus. The title track tells the story of a mythical king called Sisyphus whose punishment for deceitfulness is to eternally push a boulder to the top of a hill, only to watch it roll back down to the bottom. In some ways, this reflected the fact that Chicago were having to resist the temptations of going for the easy option of hit singles, merely to keep their record company on their side and off their back.

“We were never interested in coming up with hit songs for their own sake,” says Lamm. “They happened, of course, but not because we wanted to go in that direction. We’ve kept pushing ourselves and taking on board musical and technological changes. Even in our most successful periods, we have never sought the approval of the tastemakers, or those who choose radio playlists. We’ve had pressure applied to do more ballads, for instance, but have never done any album where that type of song was dominant.”

In a career that has seen them release 23 studio albums, Chicago have had more chart success in the US than any other American band, apart from The Beach Boys. They’ve had five Number One albums over there, as well as 21 Top 10 singles. And yet this is a band who appear to be ignored when it comes to acknowledgment of their influence on the prog scene. However, this is a situation Lamm that now feels is slowly changing as they begin to attract a younger audience.

“There appears to be a new reverence for Chicago and what we stand for. It seems a lot of prog fans have re-examined our music, which has been great for us. Of course, we have a lot of hardcore fans who’ve stuck with us for years and they’ve always understood that the big singles were never what we were about. But in more recent years, we have attracted fans who are a lot younger yet in tune with progressive music. Sometimes I look out at our audience and am amazed to see people who must be less than half my age! They don’t care when our music was made.”

But Lamm’s interests aren’t just in the music that was made during prog’s glory years – he’s also very enthusiastic about the younger bands who’ve made their mark on the scene more recently.

“Those who’ve emerged from the ’90s onwards are technically so much better than we are, but I love that. There are some very gifted musicians on the progressive scene and I love discovering new talents. I’m always on the hunt for exciting bands.”

At this point, Lamm enthusiastically asks Prog to recommend some younger artists he should be listening to. And, having been given a shortlist, just a day or two later he gets back in touch.

“I enjoy hearing fresh tunes and extended compositions, rather than just songs; the music does have a connection with early Chicago, in that sense. A lot of the best new sounds demand patience and perseverance from the listener, which is really positive. It’s a treat to hear bands like TesseracT, Transatlantic, Coshish, No-Man, Bigelf…”

Lamm, one of four original members still in Chicago, believes the prevailing sense of prog rock that’s encouraged and pursued by these fresh bands has fired the veterans to move forward artistically.

“We’ve opened our horizons on the new album, XXXVI: Now. We’re in touch again with the prog ideals which got us going in the first place. A lot of this has come from the younger elements in the genre. We aren’t trying to compete with them, but do relate to what they’re doing.”

Chicago – pioneers who are still committed to learning.

This feature originally appeared in issue 49 of Prog Magazine.

Malcolm Dome had an illustrious and celebrated career which stretched back to working for Record Mirror magazine in the late 70s and Metal Fury in the early 80s before joining Kerrang! at its launch in 1981. His first book, Encyclopedia Metallica, published in 1981, may have been the inspiration for the name of a certain band formed that same year. Dome is also credited with inventing the term "thrash metal" while writing about the Anthrax song Metal Thrashing Mad in 1984. With the launch of Classic Rock magazine in 1998 he became involved with that title, sister magazine Metal Hammer, and was a contributor to Prog magazine since its inception in 2009. He died in 2021.