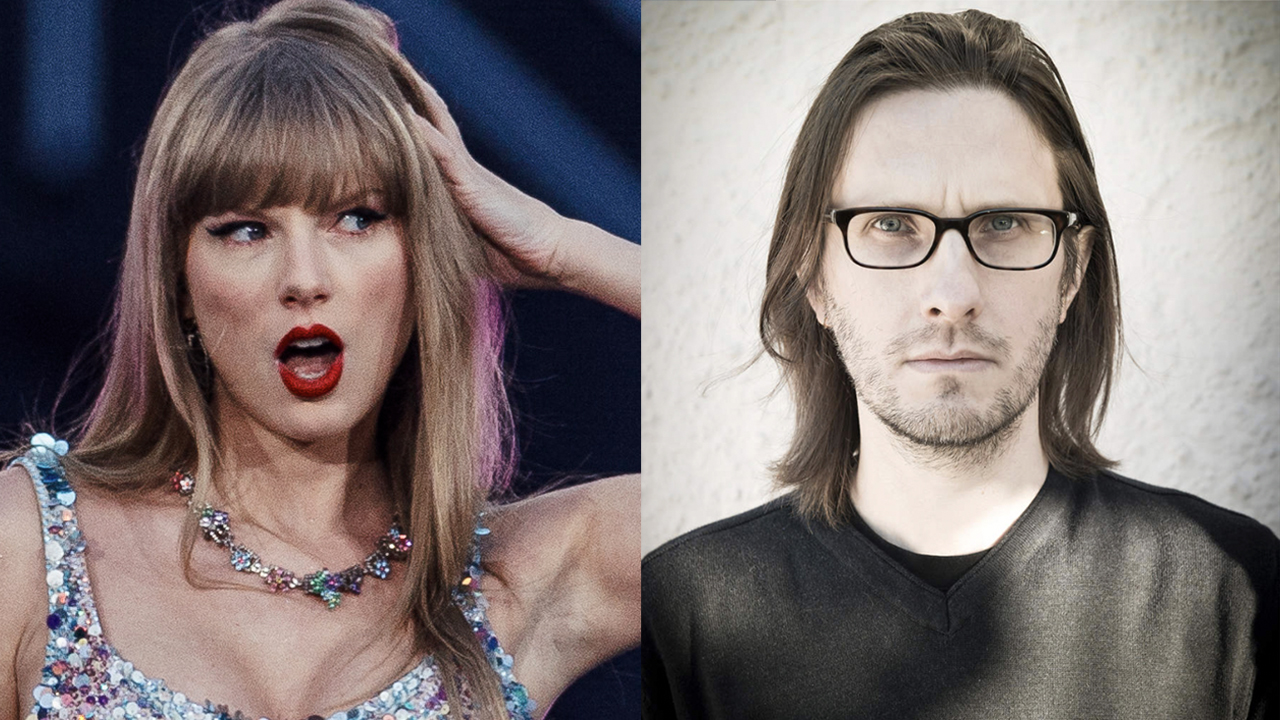

"One song took about seven weeks to do. It was insane": The Moody Blues on their best and worst albums, Charles Manson, and the mood-altering magic of Nights In White Satin

The Moody Blues were just another British R&B band. Then they got into some old clothes, mind-expanding drugs and lashings of Mellotron… and helped invent prog rock

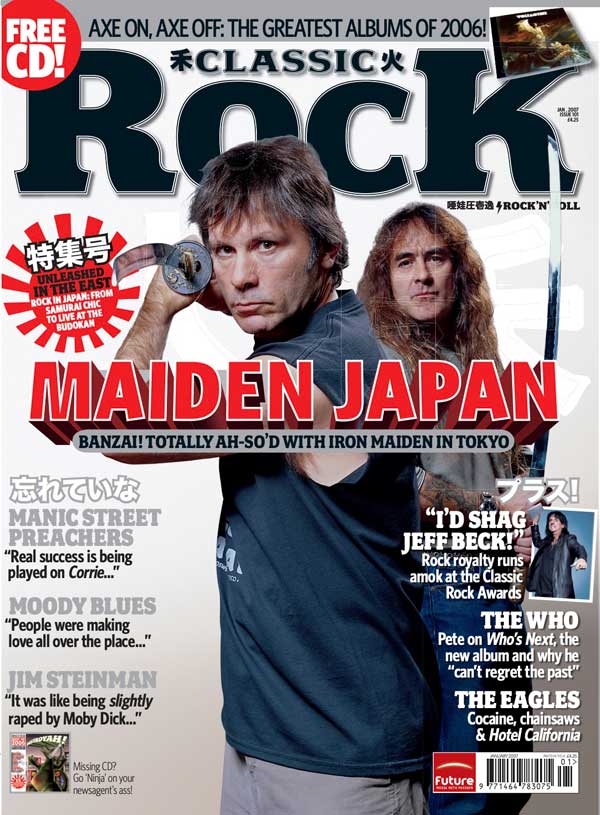

In 2006, the Moody Blues released remastered and expanded SACD versions of five albums put out at their symphonic peak, from 1967's Days Of Future Passed to 1970's A Question Of Balance. Classic Rock sat down with the band leaders John Lodge and Justin Hayward to discuss those recordings, and the conversation took in acid trips, Charles Manson and the peculiar magic of Nights In White Satin.

There are some songs that feel so warm and familiar they almost become part of your DNA, hard-wired into the nervous system. As soon as you hear them, a mood-altering experience occurs. It could be memories of childhood, fumbling adolescence, or a crap relationship. Then there are tunes that worm their way into your head and are as unwelcome as a bad hangover.

Everybody has a soundtrack to his or her life. Not always the coolest or hippest selection, nowadays these are referred to as Guilty Pleasures. Which brings us to Nights In White Satin.

This song has followed me over the decades like a relentless, rabid stalker. It’s the one with those excruciatingly pompous lyrics that are just as perplexing as the opening lines of that other 60s musical conundrum, A Whiter Shade Of Pale.

"Nights in white satin, never reaching the end/Letters I’ve written, never meaning to send."

What the hell does that mean? Until recently, I thought the opening line was ‘Knights in white satin’ – with a ‘K’ – which just added to its mystique. (Apparently, it was inspired by a set of satin bed sheets given to the songwriter by a friend.) One minute it sounds as vacuous as a theme tune to a hair shampoo commercial, yet at the right moment it can have me blubbing uncontrollably like an infant with a newly scraped knee.

It has reappeared in the charts countless times, been covered numerous times (the latest being by Glenn Hughes on his new album) and has featured in some of the coolest films, including Easy Rider, A Bronx Tale and Casino.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Straddling the boundary between genius and embarrassing parody, the song encapsulates the sound of its creators, The Moody Blues: po-faced, awash with Mellotrons and flutes, but also imbued with beautiful, timeless, enduring melodies, making it the ultimate Guilty Pleasure.

Currently celebrating 40 years in the business, the Moodies are enjoying a new wave of success. After 20-odd albums, they are still one of the highest-grossing live acts. In October, their UK tour culminated with three sold-out dates at The Royal Albert Hall. I tracked down two of the three remaining original members: bassist John Lodge and vocalist/guitarist/Nights… author Justin Hayward (drummer Graeme Edge is the other).

While Lodge is taking a well-deserved break between tours, Hayward has been busy appearing in Jeff Wayne’s War Of The Worlds, performing his solo chart topper from it, Forever Autumn. Yet in terms of press and general recognition, the Moodies fly well and truly beneath the radar and have still to be endorsed by the Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame.

“I wonder sometimes if that’s a bad thing,” ponders Hayward. “I have so many friends who are hip, and that doesn’t necessarily mean they are never going to be unhip. It’s only a few people, like Bono, who keep that balancing act going. We occasionally get reviewers saying, ‘God, they’re still going.’ Can’t say that it bothers me.”

Remastered versions of five of their most successful albums – Days Of Future Passed (1967), In Search Of The Lost Chord (1968), On the Threshold Of A Dream (1969), To Our Children’s Children’s Children (1969) and A Question Of Balance (1970) – have recently been released, each restored and expanded with a bounty of out-takes and live tracks.

The Moody Blues were fortunate to have originally signed to Decca, a label with the foresight to realise the value of preserving material for posterity, which Hayward is forever grateful for. “Our old label had a consumer division that made stereo sound systems, and these albums were recorded perfectly, unlike many others – including some by The Beatles.”

“Decca also made an exact copy of each master that was never even used,” says Lodge. “So when we decided to do the re-releases, we had access to these. A bit of a fluke, really, as we never thought there would be any future other than vinyl. It was a bit like resurrecting the Dead Sea scrolls, I suppose.”

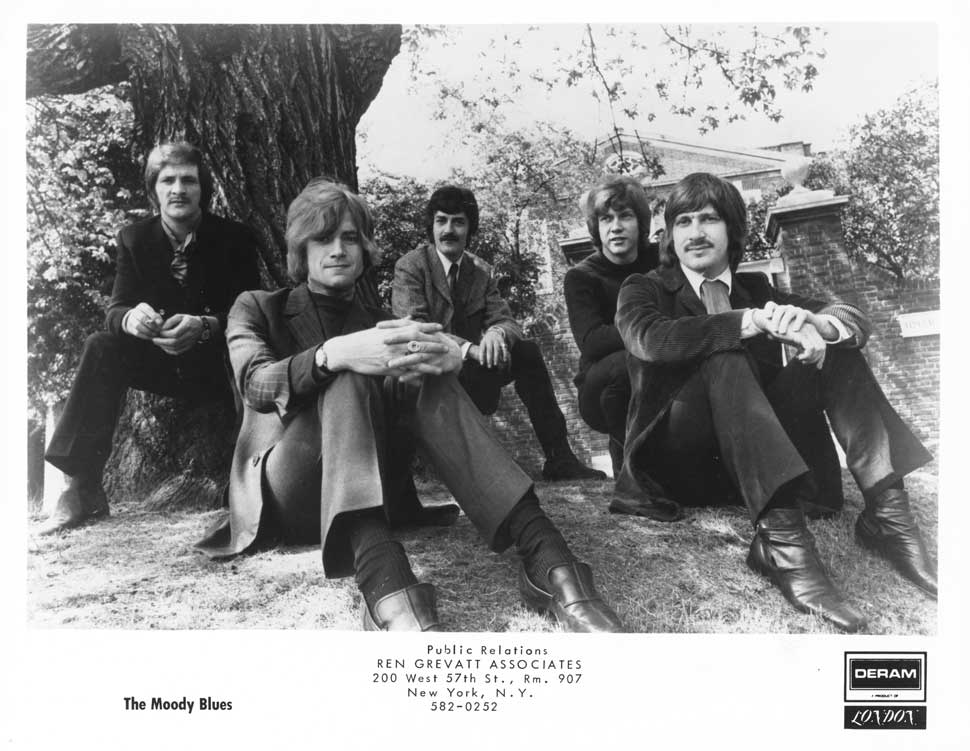

When John Lodge joined The Moody Blues in 1966, they were much like many of the other regional R&B outfits in Britain, slogging away on an endless circuit of dancehalls.

“In the 60s, all the bands looked the same,” Lodge recalls with a shudder. “They all had the same type of suits and hairstyles. We were playing the same copies of American music, but the audiences were dwindling.”

The band had scored a No.1 hit with Go Now!, a cover of an R&B standard, but a long-forgotten debut album that included it and similar material – The Magnificent Moodies – didn’t set the chart alight. The band realised that there was a dramatic musical sea change occurring, and that releasing 45s would not sustain them for long.

When the group’s lead vocalist Denny Laine left (he eventually achieved success with Paul McCartney’s Wings), the remaining members – Lodge, Edge, Mike Pinder (Mellotron, vocals) and Ray Thomas (flute, vocals) – found themselves in search of a replacement frontman. He arrived following a phone call from former Animals frontman Eric Burdon.

As Hayward recalls: “I wrote to Eric with some of my songs and, unbeknownst to me, he gave them to Mike Pinder. I met Mike first. A couple of weeks later, I met the rest of the ban,d and we were off.”

Already a successful musician, Hayward came on board armed with a collection of songs, including the formidable Nights… The band, realising that such fresh input could provide the thorough musical overhaul they needed, shut themselves away in a farm in France and wrote new material, which they tested out at local venues on their return to Britain.

“All the old clubs weren’t interested in what we were doing,” Lodge recalls. “But there were these new underground clubs opening up where nobody wanted to dance, they just sat down and listened. We also got rid of the old stage clothes and started to wear what we felt comfortable in. It was all part of the newfound freedom of the late 60s. That’s where it all developed.”

At the same time, Decca were working on a pop/ rock version of Dvorák’s New World symphony, and asked the Moodies if they would like to be involved. They initially said yes, but then decided they would prefer to embark on an orchestral concept of their own they had been working on during their creative hiatus in Europe, based on the passing of 24 hours in a day.

Fortunately, they found an ally in orchestral conductor Peter Knight, who was quite happy to shelve the Dvorák project after going to one of the Moodies’ concerts. They got support from Decca chairman Sir Edward Lewis, who was still smarting from being known as the man who turned down The Beatles. It was also their introduction to the label’s house engineer, Tony Clarke, who went on to produce the Moodies’ next eight studio albums.

Described as an ‘evocative mixture of symphonic rock music, orchestral arrangements and spoken word’, Days Of Future Passed sounds rather twee and harmless today, with its painting-by-numbers conceptual tones and light, fluffy orchestral arrangements, but the overall effect can still be mesmerising. It provided a template for future Moodies releases, and its success allowed the band to produce music on their own terms.

In the 60s, The Moody Blues were recognised as being an experimental band that successfully fused orchestral music and rock’n’roll. With their cod poeticism, whimsical imagery and soaring harmony vocals, they captured the essence of early British psychedelia and were, without a doubt, one of the progenitors of progressive rock.

Oh, and there was that monster hit song. Did Hayward feel obliged to come up with a follow-up to Nights In White Satin? “I often thought I had,” he laughs, “but five million people didn’t agree with me most of the time. There was a tremendous amount of pressure from people who said, ‘Can’t you do another one of them?’ But our whole idea of ourselves was consolidated when we went to the States. That’s when FM radio was being born, and these guys weren’t interested in singles at all. That cemented our resolve not to concentrate on singles and to start making albums.”

In America in the late 60s, The Moody Blues were immediately embraced by the burgeoning flowerpower generation, who were hypnotised by the band’s cosmic meanderings, and who were also looking for new musical gurus to replace The Beatles, who had retired from the road in 1966. This was quite apt, given that at one time both groups shared the same manager (Brian Epstein), and it was Pinder who introduced The Fab Four to the wonders of the Mellotron. Both groups also wholeheartedly embraced the hippy lifestyle, some members dabbling in hallucinogens.

“I did acid for a couple of years,” Hayward admits. “It wasn’t my number one drug of choice, but I did it and I suppose it became a part of our 60s stuff, our childlike way of looking at things.”

Titles like Om, House Of Four Doors, and I Never Thought I’d Live To Be A Hundred do suggest that their lysergic indulgences informed their music. “Oh… I don’t know,” says Hayward. “I remember having a notebook by my bed during one particular trip, and then looking at it perfectly straight a couple of days later and thinking: ‘What a load of crap!’

"But, having said that, acid has given me total recall, which is something very rare in my life,” he laughs. “You have to remember that this was during the era of free concerts – or love-ins, which were even better. Our music was perfectly suited for these occasions – smooth, gentle, mind-expanding. People would come along and make love all over the place.”

Profligate use of mind-expanding drugs produced more than a few casualties in the 60s, and the Moodies found themselves with some rather crazy and controversial followers, including infamous Manson (Charlie, not Marilyn) disciple Lynette ‘Squeaky’ Fromme.

“Squeaky was a big Moodies follower,” Hayward says. “I think there might have been a time when we almost went to have a look at the Manson ranch. She was, of course, later convicted of trying to wipe out the president who couldn’t chew gum and walk at the same time [Gerald Ford, in 1975]. We’ve always attracted a lot of very, very strange people as well as a lot of beautiful people.”

By 1972, the Justin Hayward-fronted Moody Blues had recorded seven albums – the other two in the remastered series, Every Good Boy Deserves Favour (1971) and Seventh Sojourn (1972) are scheduled to be released in the near future. Coupled with the constant touring, burnout was inevitable. An extended break was needed during which various members worked on solo projects. The group also formed their own label, Threshold, which, as well as being a vehicle for Moodies releases, was also an outlet for new talent (including rock/funk stalwarts Trapeze, featuring future Deep Purple vocalist/ bassist Glenn Hughes).

In ’77, the Moodies reunited and recorded Octave. It was an unexpected success. “What people can’t have, they want even more. And that was very much the case with the Moodies,” Hayward says. “But while we maintained our stature, we lost our independence. When we came back with Octave, we were at the mercy of A&R men and people in the business. Up until then, we pretty well managed our own affairs.”

Soon after the release of Octave, founder member Mike Pinder left, refusing to go on tour. He was soon followed by producer Tony Clarke. The late 70s/early 80s, then, was a particularly unsettling time for the group, as Hayward acknowledges: “Mike had given us what we didn’t have any more: the Mellotron sound that he created. Tony gave us the direction.”

Left to their own devices, some of the band succumbed to the excesses of rock’n’roll. A “disastrous” album (Hayward’s description), The Present, followed in 1983.

“This was the lowest point for us,” says Hayward. “The Present was a cocaine record – rubbish, really. One song took about seven weeks to do. It was insane. The drugs became a struggle for a couple of people in and around the band. It was a very uncomfortable and stupid time. The only good thing about it was that I met producer Tony Visconti [who produced their next album, 1986’s The Other Side Of Life]. Meeting him turned me around as a writer and a person. The success we had with him in the mid-80s is certainly the reason we are here now.”

Even though The Moody Blues still produce new material, Hayward accepts that it’s their early records that are responsible for, and still underpin, the band’s continued success.

“The obsession with the old is very time-consuming,” sighs Hayward. “We get offered so much work we could gig every day of the year. In fact, we’re offered more work now than we were in the early days. I think there’s always an interest in The Moody Blues, and that surprises me. Even talking about it now, the fact that Classic Rock are interested, I think it’s just wonderful, because I can re-live all that stuff again. Fantastic!”

Ever optimistic, grateful and steeped in the old hippy idealism, it’s hard to dislike The Moody Blues. They are the big woolly jumper of prog. Never dangerous but often adventurous, they are the ultimate Guilty Pleasure. And their self-effacing sense of humour helps.

As Justin Hayward concludes, “The whole thing has been so Spinal Tap. I can always see that element when I read reviews. I look back and sometimes think: ‘God, we never smiled in a picture until 1983.’ All I can say is that everything we’ve done has been honest and from the heart. Whether it’s sad or not, we really meant it.”

This feature originally appeared in Classic Rock 101, published in January 2007. The Moody Blues were inducted into the Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame in 2018.

Pete Makowski joined Sounds music weekly aged 15 as a messenger boy, and was soon reviewing albums and doing interviews with his favourite bands. He also wrote for Kerrang!, Soundcheck, Metal Hammer and This Is Rock, and was a press officer for Black Sabbath, Hawkwind, Motörhead, the New York Dolls and more. Sounds Editor Geoff Barton introduced Makowski to photographer Ross Halfin with the words, “You’ll be bad for each other,” creating a partnership that spanned three decades. Halfin and Makowski worked on dozens of articles for Classic Rock in the 00-10s, bringing back stories that crackled with humour and insight. Pete died in November 2021.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

![Moody Blues - Go Now [HD] - YouTube](https://img.youtube.com/vi/V2L3UzM_FfE/maxresdefault.jpg)