Nick Cave's best albums: your essential, chronological guide

Over the last 40 years, Nick Cave's albums have marked him out as a singular talent in alternative music – here, we go through his most significant musical moments

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

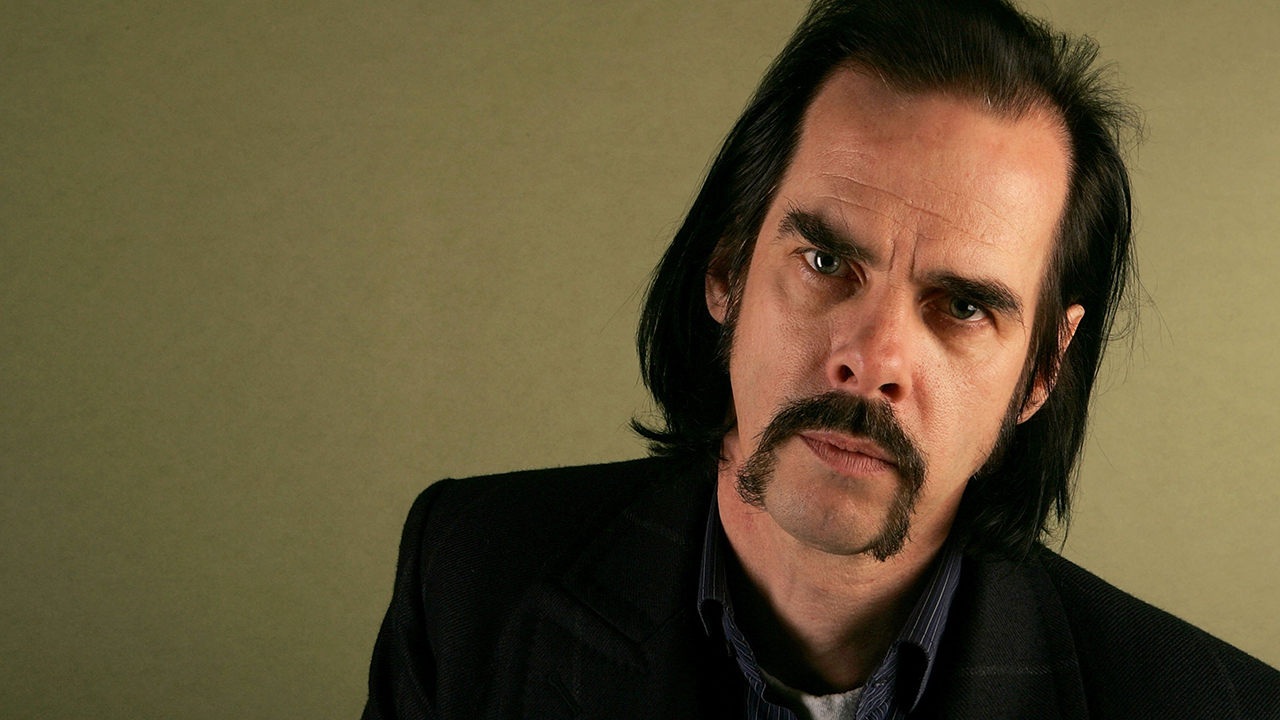

With the best will in the world, few musicians would expect, at the age of 62, to be hitting the peak of their critical and commercial appeal. And yet, with the surprise release of the new Bad Seeds album, Ghosteen, this is exactly the position Nick Cave finds himself in today.

Thanks in part to the exposure of his music on the likes of TV show Peaky Blinders, his presence in the mainstream consciousness is stronger than ever. But after four decades of delighting his unfailingly loyal fanbase with unique and vivid songs of violence, religion, madness, intense love and great beauty, it’s his ever-deepening relationship with his audience, triggered by personal tragedy, that has reignited the fire that’s burned throughout his finest moments.

This stands in concert – intense congregations in which he takes the lead as shadowy preacher bordering cult leader; in his unflinchingly honest, emotionally open Q&A sessions; or in the Red Hand Files, a series of emails answering fans’ questions (“you can ask me anything”) and offering advice that veers from wryly hilarious for more flippant correspondents, to deeply moving (his thoughts on grief are, understandably given the death of his son Arthur in 2015, particularly beautiful), but always reveal a sense of kindness and empathy that has clearly come with age and experience.

It’s a vast change from the drug-fuelled, emaciated aggression and antagonism of his early days in The Birthday Party, a band dubbed the most violent in Britain at the time and one who openly despised their own audiences, or from the shamelessly salacious garage rock he produced with Bad Seeds offshoot Grinderman. But with each new chapter, Cave reveals a part of himself previously unseen, and his back catalogue becomes a little more complete.

Here, we look back at some of the significant musical moments in Cave’s history.

The Birthday Party: where it all began (1976-1983)

Having formed in the early 70s at school in Melbourne as The Boys Next Door – featuring Cave, guitarist Mick Harvey and drummer Phil Calvert, and later bassist Tracey Pew and guitarist Rowland S Howard – it took a while for the band to find their feet, the fizzy post-punk of their 1979 debut Door, Door since described by the frontman as “complete wank”.

Renamed The Birthday Party and taking on an inky, chaotic and bold discordance for their 1980 self-titled debut, they then relocated to London, signed to 4AD and become almost instantly disillusioned with the scene and the bands surrounding them.

A sense of aggressive isolation flows through 1981’s Prayers On Fire, where Cave’s persona as theatrical, shoelace-thin, shock-haired ringmaster emerged, with a dark, carnivalesque feel that’s only really comparable to Tom Waits in full flight.

By the time of Junkyard (1982), The Birthday Party’s final (and finest) hour, a shamanic and magnetic Cave had perfected a Southern Gothic style that became his signature, a sense of rat-infested humidity and overheated religious fervour leading his characters down dark, violent and murderous paths.

This was nihilistic blues entirely reinvented for the punk generation, so wonderfully vivid you can practically smell the blood. Unfortunately, by now, much of the audience was made up of people turning up just to fight the band and each other ("I don't know of another group who are playing music that is attempting in some way to be innovative that draws a more moronic audience than The Birthday Party,” he told NME. “There's always 10 rows of the most cretinous sector of the community”), while addiction to alcohol and heroin within their ranks were amping up the tension, signalling a sour end for The Birthday Party.

But new beginnings around the corner in the shape of the Bad Seeds.

Nick Cave And The Bad Seeds: the first wave (1983-1986)

Having reconvened with Mick Harvey, alongside a new band including Einstürzende Neubauten’s Blixa Bargeld and Magazine’s Barry Adamson, Cave’s Bad Seeds debut, From Her To Eternity (1984), moved further away from their punk roots, bringing in an atmospheric sense of experimental musicianship that paved the way for the lush orchestration to come, while keeping the foundations rooted in a dark blues.

Its follow-up, 1985's The First Born Is Dead, though, took the blueprint and sent a bolt of lightning through it – literally, opener Tupelo’s opening crack of thunder and downpour offering the most cinematic use of weather in a song since Black Sabbath. Its tale of devastating floods in Elvis Presley’s hometown set the stage for the album’s stunningly handled fixation with the original blues masters and the deep south, the band embodying the genre without ever falling into pastiche.

Ingeniously, they followed it up with Kicking Against The Pricks (1986). A magnificent album of covers featuring blues classics from Leadbelly and John Lee Hooker, Cave mixed it up with country (Jimmy Webb’s By The Time I Get To Phoenix, Johnny Cash’s The Singer), epic pop (Gene Pitney’s Something’s Gotten Hold Of My Heart), classic rock’n’roll (a creepshow take on Jimi Hendrix’s Hey Joe) and stoned east-coast art-rock (a spiky version of The Velvet Underground’s All Tomorrow’s Parties), and not only demonstrated the vast range of styles they could take apart and remould in their own image, but also deftly ensured they’d never run the risk of being pigeonholed again.

Nick Cave And The Bad Seeds: a stylistic shift (1986-1990)

After years of swagger, there’s a sense of wintery sadness running through 1986's Your Funeral, My Trial, and its difficult not to attribute it at least in part to the heroin addiction Cave was plagued by at the time it was made.

Even at its most theatrical, as on the vivid tale of a missing circus performer on The Carny, it often feels more like a novel set to music than a traditional rock album. It’s more collaborative, too; its centrepiece – the beautifully melancholy Stranger Than Kindness – written by Bargeld and Cave’s then-partner Anita Lane, who clearly had an intense understanding of what made the singer tick.

Their dark Berlin period continued into Tender Prey (1988), although sonically it was an about-turn from its predecessor. Opening explosively with The Mercy Seat, a terrifying testimony from a condemned man as he graphically describes his final moments in the electric chair (and later brilliantly reimagined by Johnny Cash), it flows from spunky Bonnie and Clyde garage rock (Deanna) to sparse moments of bleak drama (City Of Refuge, with its distant weeping harmonica willing a man on the run along his way).

There was light at the end of the tunnel though. By the time of 1990’s The Good Son, Cave was sober, in love and living in Brazil with his first wife Vivienne Carneiro, and the record takes on an entirely gentler tone, opening with Brazilian hymn Foi Na Cruz woven into Cave’s own musings on the struggles of romance.

The highlights, though, are The Ship Song, a delicate and deeply beautiful love song, and The Weeping Song, a singular sea shanty that shows the Cave and Bargeld partnership at its most mesmerising.

Nick Cave And The Bad Seeds: the darker side of love (1992-1994)

While 1992’s Henry’s Dream offered up Cave’s most unashamedly straightforward romantic song to date in the sweeping Straight To You, the more dangerous side of human relationships rears its ugly head in its follow-up, 1994's Let Love In.

From the aggressive and disturbing infatuation of opener Do You Love Me – a song so sodden with obsession it raises itself from the dead for a reprise at the end of the record – to the bleak abandonment and heartbreak of Nobody’s Baby Now, a song that sees him examine his own destructive cruelty and subsequent trail of emotional destruction, Cave digs deep into the darker side of love.

Indeed, the intense and threatening Loverman ('there’s a devil waiting outside your door') paints a portrait of a stalker and control freak, just one more of the disturbing characters Cave has created from the depths of his psyche over the years.

It’s not all lustful entanglements, though. There’s murder too. With its tolling bells and creeping melody, Red Right Hand is a spectacular piece of storytelling from the criminal underworld, a vivid portrayal of a man who can bring about absolute destruction. No wonder the team behind Peaky Blinders based the show’s entire soundtrack around it – this is cinema made into song, and remains as electrifying today as it was 25 years ago.

Nick Cave And The Bad Seeds: songs of depravity and death (1996)

As concept albums go, 1996's Murder Ballads takes some beating – and dishes plenty out, too. An orgy of violence and death, it takes in traditional songs of slaughter as well as some originals, leaving a landscape strewn with bodies slain for reasons both righteous and evil.

As with early Tarantino, there’s a blackened gallows humour to much of the carnage, not least in Stagger Lee, in which the protagonist’s crimes reach ever more extreme depths of depravity, or O’Malley’s Bar, a one-man western shootout of madly epic proportions.

Elsewhere are moments of beautiful tragedy, not least in Where The Wild Roses Go. Their biggest hit to date was a duet that saw a wide-eyed and innocent Kylie Minogue lured to her doom with the promise of a romantic happy-ever-after, bathed in a southern-swamp humidity that elevates it to literature.

Another duet, Henry Lee, with Cave’s then-partner PJ Harvey, turns the tables, the female suitor turning aggressor. The album the Bad Seeds had been building towards for years, Murder Ballads remains an immersive listening experience that few musicians could hope to compete with.

Nick Cave And The Bad Seeds: heroin and heartbreak (1997)

In a recent Red Hand Files entry, Cave was asked about his split from PJ Harvey (“I was so surprised I almost dropped my syringe,” he wrote with typical irony in response to being told it was over). Aside from discussing the relationship itself, he goes on to talk about the “lunatic energy” it gave him: “Songwriting completely consumed me at the time.” He also sites a more “feminine energy” leading to a “wiser, more empathetic” record as a reason it appealed to a wider audience than anything he had previously worked on.

Certainly, there is a gentleness at work in 1997's The Boatman's Call that may have been obscured before, the longing piano ballad Into My Arms stripping away all machismo to reveal pure emotional transparency that can break a heart in seconds.

There’s also the impression that it is being sung directly to one person: Harvey. Her face, her mannerisms, tiny little parts of her character are gazed upon and obsessively worshipped in West Country Girl, Black Hair and Green Eyes, while (Are You) The One That I’ve Been Waiting For? finds Cave ripping his bloody heart out of his chest and nailing it to his sleeve.

Richly enhanced with religious imagery, and without the veil of fictional characters, this is mid-period Cave at his most vulnerable and is absolutely essential.

Nick Cave And The Bad Seeds: a mended heart and a new millennium (2001-2004)

A four-year hiatus followed The Boatman’s Call, during which time Cave struggled with alcohol and heroin addiction. The band returned in 2001 with the remarkably tender, philosophical No More Shall We Part, although its follow-up, 2003’s Nocturama, is a rare inessential misstep, which is a shame as it was Blixa Bargeld’s parting shot before leaving the band.

Double album Abattoir Blues/The Lyre Of Orpheus, though, came back swinging in 2004. Rollicking opener Get Ready For Love features a knockout appearance from the London Community Gospel Choir, and Cave himself sounding like a man reborn.

With his heart clearly mended from The Boatman’s Call days, Abattoir Blues – the rock side of the pairing – hums with Cave’s unique wit and a new sense of joy, while drummer Jim Sclavunos drives the whole thing along mercilessly, and it all points to the garage rock to come with the Grinderman project.

The Lyre Of Orpheus side, meanwhile, is more considered and artful, delving to the Ancient Greek mythology of musician and poet Orphus, tackled brilliantly with Cave’s tongue placed firmly in his cheek. A staggering return to form, the album acted as a reset button for Cave to stretch his creative muscles away from a strain of maudlin balladry he could so easily have settled into.

Grinderman: Cave cuts loose (2007-2010)

There’s a great joy to be found in listening to a favourite artist kicking loose from the shackles of commercial expectations and industry needs and just having an absolute blast, and Bad Seeds offshoot Grinderman offers just that.

Recorded in a four-day flurry, with a mandate of no love songs and no God stuff, Grinderman (2007) is the most raw and rude Cave has sounded since The Birthday Party days, as evidenced on the entirely shameless No Pussy Blues. Grinderman 2 followed in 2010, a little more polished but still a refreshing outlet for the band.

Dig!!! Lazarus, Dig!!! (2008) followed the first Grinderman album, and it was an instant return to weightier topics – although Cave’s sense of inky wit was fully at the fore of the opening title track, a blast of garage rock that shifts the biblical story of Lazarus to the grubby modern-day streets of New York City, wryly questioning whether he actually wanted to be raised from the dead.

There’s a wonderful, rejuvenated looseness to the record, and a pure poetic enjoyment in playing with words from the frontman, all providing an admirable last hurrah for founder member Mick Harvey, who left shortly afterwards.

Nick Cave And The Bad Seeds: Growth and grief (2013-2016)

The Bad Seeds took a minimalist approach to their 2013 album Push The Sky Away, an elegant but enigmatic record described by Cave as a “ghost-baby in the incubator, and Warren [Ellis]’s loops are its tiny, trembling heart-beat”. The recording process was documented in the film 20,000 Days On Earth, a glimpse into the creative process and into the complex relationships between the key players.

During the recording of its follow-up, Skeleton Tree (2016), unimaginable tragedy hit Cave’s family when his 15-year-old son, Arthur, died after falling from a clifftop. While most of the lyrics had been completed by that time, the frontman revisited some of them, and with its minimalist sound and musings on grief, it’s impossible to separate the record from that terrible loss.

It was again accompanied by a documentary, One More Time With Feeling, but this time it was an overwhelmingly emotional affair that served to put the album in context and also allowed Cave to avoid the additional pain of talking to the media during its promotional run.

With an emphasis on ambient sound, Skeleton Tree is a delicate thing of avant-garde wonder, a tough listen but a truly rewarding one.

Nick Cave And The Bad Seeds: Ghosteen (2019)

As David Bowie’s Blackstar showed, great personal trauma can lead to great artistic triumph. With Ghosteen, the first album written entirely in the aftermath of the loss of his son, Cave and the band have conjured a work of such astonishing, devastating, thoughtful beauty it transcends genre and even medium to aim straight for the soul.

As with its two most recent predecessors, the music here is ambient, floating in space, dreamlike and softly cushioning Cave’s warm vocals to allow them to take centre stage.

Where once you would have expected rage, fire and brimstone, revenge, here Cave is philosopher and poet, a man with no layers left to strip away as he explores the days, months and years after the initial gut-punch of grief.

Religious imagery once again plays its part, from Christian to Buddhist, while love has moved on from romantic to both paternal and something more universal (“Everybody’s losing someone,” he laments in devastating closer Hollywood, from the second part of the album that speaks of nights spent in extreme torment). At moments it feels overwhelming, as if we shouldn’t be listening in on something so personal.

But listen we must, as it’s a masterpiece, and the greatest tribute of all.

The latest news, features and interviews direct to your inbox, from the global home of alternative music.

Emma has been writing about music for 25 years, and is a regular contributor to Classic Rock, Metal Hammer, Prog and Louder. During that time her words have also appeared in publications including Kerrang!, Melody Maker, Select, The Blues Magazine and many more. She is also a professional pedant and grammar nerd and has worked as a copy editor on everything from film titles through to high-end property magazines. In her spare time, when not at gigs, you’ll find her at her local stables hanging out with a bunch of extremely characterful horses.