A beginner's guide to Dire Straits in seven essential albums

More than Brothers In Arms: The Dire Straits albums you need to know

From 1978’s self-titled debut to the hit-and-miss coda of 1991’s On Every Street – via arguably the best live record of all time – Dire Straits’ back catalogue runs far deeper and richer than Brothers In Arms.

This is the story of Mark Knopfler's men, told through seven very different albums.

Dire Straits (1978)

You can trust Louder

The late-70s pub circuit of South London was an inauspicious launch pad (“Deptford was an armpit back then”) and Knopfler’s men – career sloggers perilously close to their thirties – could easily have ossified into the no-hoper jazz band he so candidly observed on Sultans Of Swing.

But with no small irony, the demo of that song – chronicling the small, sad, thwarted lives of wetback working musicians – pricked up the ears of BBC Radio London’s Charlie Gillett, which helped speed Dire Straits to a deal with Vertigo/Warner and sessions at Basing Street Studios.

On the debut album they made there, what had seemed like an impediment – Knopfler’s old-soul earthiness and lack of Jagger-style pizazz – emerged as a strength, the lugubrious singer spinning tales of his native Newcastle’s smoky shipyards on highlights like Down To The Waterline with an authenticity that was plainly under his fingernails. “If you haven’t unloaded a lorry,” he once reflected, “you can never quite come to grips with reality.”

As a guitarist, too, Knopfler was already fully formed and in a different class to the punk scene’s stragglers, and the quicksilver bob ‘n’ weave outro of Sultans sent the song to No.8 on home turf, and helped its parent album to UK No.5/US No.2. For better or worse, the boulder was rolling.

Communiqué (1979)

Communiqué sold three million copies. Yet markers of a band on the rise belied a follow-up that Knopfler simply “didn’t think was a very good record”. For some, the rapid turnaround of this second was suspect (“The songs sound like pale imitations,” sniffed the Birmingham Daily Post, “or the cuts that were not good enough for the Dire Straits album”).

In the States, meanwhile, Knopfler complained of Uncle Sam’s “hang-up” as his new material scraped to No.11 and the critics came after him. “Dire Straits appear to be trapped in a creative impasse,” said the Los Angeles Times, “and Communiqué is marked by an overwhelming sense of déjà vu.”

Almost half a century later, with the weight of expectation lifted, there’s gold here: try Once Upon A Time In The West’s slow-burn shuffle, the mournful strum of Where Do You Think You’re Going? or the effervescent and still lovely Lady Writer. None of that moved the needle in ’79, however, and as implied by Communiqué’s no-show on 2005’s best-of compilation Private Investigations, Communiqué remains an underrated blind spot for all but the most ardent Straits fans.

Making Movies (1980)

Interviewed by Classic Rock’s Dave Everley in 2019, Knopfler claimed to have “always” held the reins of Dire Straits. But the bandleader’s grip palpably tightened with Making Movies, a fantastic third album whose personnel issues (kid brother David dropped out of the line-up during sessions) couldn’t tarnish the first new songs to truly rival Sultans Of Swing.

“Making Movies was closer to what I like to do,” Knopfler told interviewer Bill Flanagan. “On that record I was determined I would not be immobilised by anything.”

The album sales and streaming figures support the official line that Brothers In Arms is Dire Straits’ best record. Revisit Making Movies now, however, and the podium finish is harder to call. These remain uncommonly strong songs: the wounded resonator pluck of Romeo And Juliet, Skateaway’s plaintive, instant-classic chorus, the tough riffing of Expresso Love… Everything, in fact, apart from the honkingly bad ode to the German gay club scene, Les Boys.

Meanwhile, the hiring of Springsteen’s mix-master Jimmy Iovine on production paid the greatest dividends on stunning opener Tunnel Of Love. With its tale of a lost love set against the backdrop of the North-East’s fading seaside towns – capped by a glorious outro guitar solo that aches alongside the lyric – it boasts both the small-town storytelling smarts and skyscraping musical ambition of The Boss at the peak of his powers. Has Knopfler written a better song?

Love Over Gold (1982)

Settling in at the Power Station to self-produce Love Over Gold, Knopfler emerged with a fourth release that, along with Communiqué, is usually missing from the collections of casual fans. At first glance, with just five songs, Love Over Gold smacked more of a stopgap EP than a proper album, but that was to overlook the sprawl of Side A’s two long-form masterpieces.

Of these, Private Investigations remains one of the most obtuse-yet-brilliant hit singles in British rock: a seven-minute film-noir that flows from mournful nylon-string flamenco to a closing section alternating between John Illsley’s spooky staccato bass and Knopfler’s jump-scare guitar blasts (somehow it still made UK No.2). Longer still, at 14 minutes, and even more impressive is Telegraph Road the epic tale of a dirt track’s evolution into a community, written by Knopfler while he sat in the tour bus as it carved along Michigan’s famed Highway 24, thumbing Norwegian author Knut Hamsun’s Growth Of The Soil.

By comparison, the second side inevitably felt a bit slight. Perhaps the tracklisting would have been stronger, and the album more famous, had the Straits not gifted Private Dancer to Tina Turner. Then again, the thought of Knopfler singing it is ridiculous.

Alchemy: Dire Straits Live (1984)

Cherry-picked from two Hammersmith Odeon shows at the tail end of 1983’s Love Over Gold tour, Dire Straits’ first live album remains their best. Listen to Alchemy now and there’s a case that no band ever batted their material around more daringly live. The prelude to each song is often as long as the track itself, as if Knopfler’s players are composing in real-time, with the audience audibly surprised as a familiar hook finally arises from the jam.

You could argue that the timing of its release inevitably means Alchemy feels a little incomplete (there’s no Brothers In Arms songs here, for example), while the occasional iffy synth tone plants it unmistakably in the early 80s. Yet these performances take the studio originals right to the wire and sometimes beat them (after hearing Alchemy’s bone-rattling spin down Telegraph Road, the Love Over Gold version sounds treacle-torpid).

Sultans swings, and the Tunnel Of Love outro solo is milked to shiver-and-tingle effect. But the ace in the hole here is Knopfler’s Going Home theme from the Local Hero movie: a wordless yet profound instrumental finale whose wistful preamble is punctured thrillingly by the sunbeam of that Celtic-sounding fanfare.

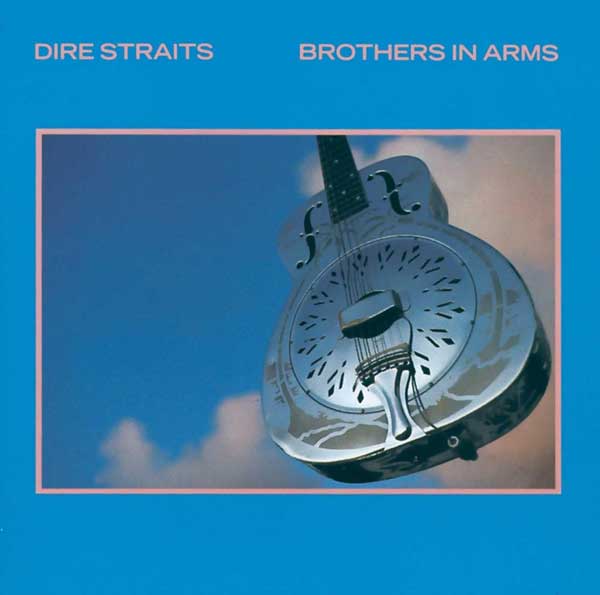

Brothers In Arms (1985)

Accepted wisdom has it that Brothers In Arms was Dire Straits’ most brazenly commercial record, a near volte-face from its intricately layered predecessor of 1982, Love Over Gold. Certainly, BIA is home to a couple of Mark Knopfler’s most everyman songs, Walk Of Life and, but of course, Money For Nothing. Equally, the then-trailblazing digital production made it a perfectly polished fit for both FM radio in the US and the dawning age of the compact disc.

And yet, the actual truth is somewhat more nuanced. For not so far beneath its gleaming hood, Brothers In Arms was trickier, not so easy to pin down. If lugubrious opening track So Far Away could have resided on any of the band’s previous four albums, Your Latest Trick evoked an altogether different sense of weary, late-night melancholy. Then there were Ride Across The River and the closing title track, Knopfler stretching both himself and his band out across more cinematic and hauntingly atmospheric terrain.

With Omar Hakim’s dazzling percussive embellishments and the fact Knopfler had never sung or played better added into the mix, the Straits’ biggest selling record is also their most consistently excellent. Timeless, in a catch-all word.

On Every Street (1991)

The silence following Brothers In Arms said it all (“After that tour,” Illsley told this writer, “there was a definite feeling we had to put this to bed for a while and recover from all the attention”).

Released six years later into a post-Nirvana universe, On Every Street felt like it came from another century entirely. Yet while the zeitgeist was by now a distant dot to Knopfler and co, this sixth album is far from a death rattle. From the bee-in-a-bottle groove of Calling Elvis to the title track’s aching pre-internet search for a lost lover, there was enough here to sign off Dire Straits’ studio career with credit. But when On Every Street misfired – the faux-hellraising Heavy Fuel, or Knopfler’s baffling host-with-the-most persona from My Parties – you couldn’t argue with the lukewarm reviews.

Whatever. By then the bandleader was counting down the tour dates until he would at last be free. “I was burnt out, shredded,” he told Classic Rock of the final straight. “I remember being in Amsterdam, lying on my bed, feeling like somebody had pulled all the wool out of me.”

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Paul Rees been a professional writer and journalist for more than 20 years. He was Editor-in-Chief of the music magazines Q and Kerrang! for a total of 13 years and during that period interviewed everyone from Sir Paul McCartney, Madonna and Bruce Springsteen to Noel Gallagher, Adele and Take That. His work has also been published in the Sunday Times, the Telegraph, the Independent, the Evening Standard, the Sunday Express, Classic Rock, Outdoor Fitness, When Saturday Comes and a range of international periodicals.