“I refused to believe the negative things he said because I couldn’t lose hope. But everything he said came to pass”: Terry Bozzio asked a question when he joined Frank Zappa. He asked the same question when he left

Drummer, composer and painter recalls his experiences with Captain Beefheart, UK and others, names the best band he’s ever been in and reveals how long it takes to set up his Big Kit

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

In 2017 drummer, composer and painter Terry Bozzio looked back on a career that features experiences with Frank Zappa, Captain Beefheart, UK and others, and summarised what he’d learned from it all.

Terry Bozzio isn’t known for sitting back and taking things easy. The Grammy-winning drummer, who came to prominence with Frank Zappa albums such as Zoot Allures and Sheik Yerbouti in the 1970s, is a self-confessed workaholic. His turbocharged drumming helped propel UK’s Danger Money and Night After Night after Bill Bruford and Allan Holdsworth left the ranks. Boasting stints with Jeff Beck, Quincy Jones and Mick Jagger, Bozzio has also fronted his own bands, including his post-punk synth-tinged pop outfit, Missing Persons, and the eclectic improv-supergroup HoBoLeMa, with Holdsworth and King Crimson’s Tony Levin and Pat Mastelotto.

Encouraged by Zappa and famed musicologist Nicolas Slonimsky, he developed a taste for composing music that took him beyond rock and jazz, resulting in his contemporary classical chamber works performed by the Metropole Orchestra in 2003

When he’s not up to his neck in some aspect of music production, he’s an avid painter. Captain Beefheart suggested the idea when they toured together in Zappa’s band. Bozzio’s abstract canvases have become collectible in recent years.

When Prog speaks to Bozzio at his home in Southern California, we enquire, only half-jokingly, how he manages to stay alert and on-track with it all. “Coffee, Ritalin, nicotine!” he quips.

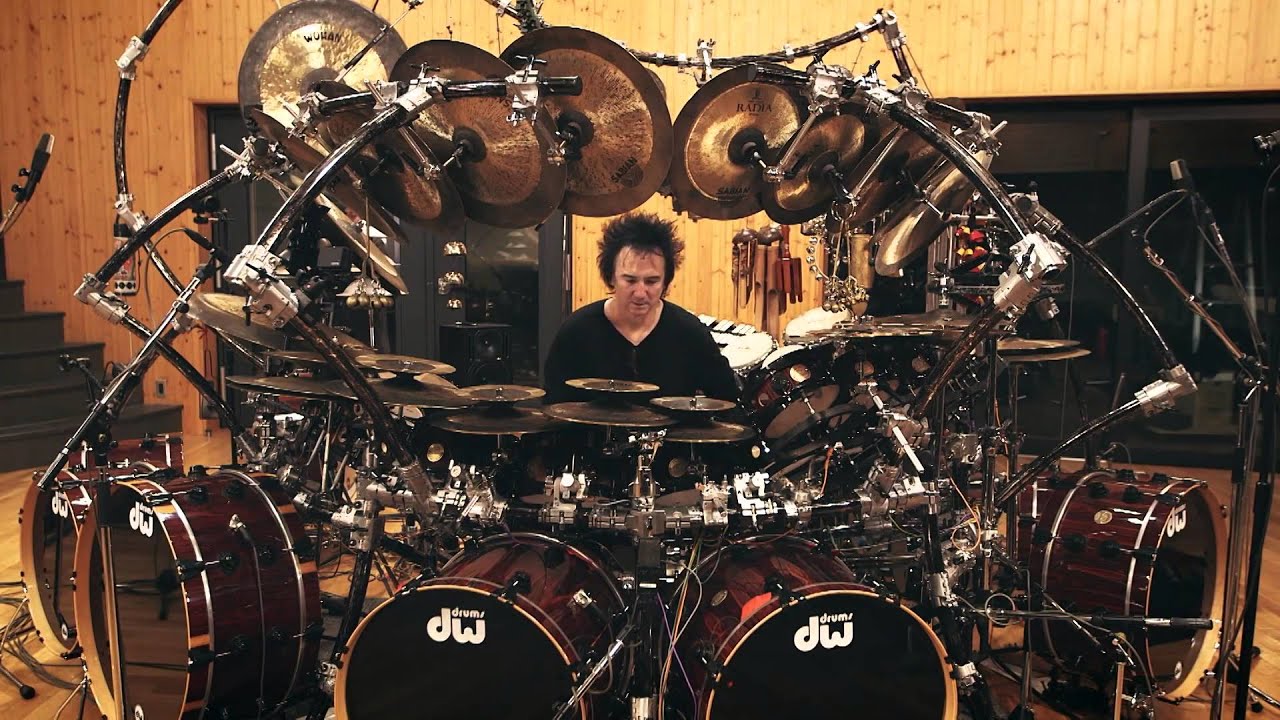

Given the complexity of The Big Kit, with its hundreds of individual drums, cymbals, mallet instruments and so on, it seems safe to assume you’re a details kind of guy.

I spend more time under the hood with that thing, building and tweaking it, than I do actually playing and practising it, because if these little things aren’t right then I’m distracted from this creative flow. You have to get all those little things right.

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

How long does it take to set up ?

Now it has a MIDI set-up, micing and my own sound system, it’s gone up to about four hours comfortably. We could get it up in two at a push. The best it’s ever been put up in with soundcheck and everything was 45 minutes – a real record with a bunch of people who knew my kit helping out.

Where did the idea for it come from?

The first rack I made was like a cage. I was looking at it and thinking, “Why am I putting these beautiful round drums and cymbals in this square cage?” So I made the rack curved and more sculptural, following the form of the instruments and how they graduated from high to low, large to small.

I sometimes build these racks and I don’t even want to put drums on them, they’re so beautiful as sculptures! There’s a quote by Neil Peart about when he sat down at my drumset – he said, “Wow, this is his mind. This is his mind in drums!”

In your solo work there’s something almost ceremonial about what you do. Is the look of the thing as important as the sound?

Yes. Every detail is important. In a live performance you see with eyes as well as your ears. You listen on many levels: intellectual, physical, emotional and intuition. I think I’m more balanced sitting behind the drums in those four areas than anywhere else. The fifth element is the divine – that Big Bang that animates this whole thing.

Some artists prefer to let their music speak for itself. But in your Composer Series box set, you wrote precise notes for each track.

I can think back to things that inspired me, like The Rite Of Spring by Stravinsky. I loved that music, then I happened to read some liner notes that were on an album of it and I realised then it was a ballet, and there was choreography and a whole mythological storyline to it as well. There was all this depth that I didn’t know about. Reading all that enhanced the listening experience. Initially I was just happy listening, but then there’s all these other levels going on which made a difference to how I heard it and helped me appreciate it even more.

Many times Frank used words I didn’t understand and I’d just laugh because I didn’t want to appear stupid. I wish I’d asked what the words meant

What’s your approach when composing?

It’s like working a crossword puzzle: this has to work this way and that way, horizontally and vertically on a line of time. You follow where these things take you. I work in intervals with music – if there’s one note, I can hear where the next note should be and I go there. After a while of chipping away at it, day after day, you have this body of work. When I played with the Metropole Orchestra I remember talking to the bass clarinet player and he said, ‘Did you really write all this stuff?’ I told him: ‘One note at a time!’

Is it important to pull pieces together into one place – a grand statement of sorts?

People know me as I played with this guy or that guy, and they know my solo drum music, but they don’t really know about this other side of me, the art and the compositions. So I wanted to share what my experiences are and what my approach is to each tune. I enjoy writing about the music and sharing my feelings and the technical aspects with others so they can learn or grow from it – if they’re interested.

Somehow this is the essence of us; it’s what we need to do to find our own bliss: knowing I’ve created something that satisfies me. And if I can like it – as critical and as cynical as I am – then maybe others will like it too. Maybe not in my lifetime, but it’s there. It really is that kind of feeling when you do something that you love and you finally got it out. Whether it sells or not doesn’t matter. You did it.

You’d had quite a lot of experience before your audition for Frank Zappa. But was it still daunting?

It was amazing! He said he wanted to hear me after he’d heard the rest of the guys, and nobody wanted to audition after me. He said, “It looks like you’ve got the gig if you want it.” My words were, “Are you sure I can do this?” He said, “Do you want to do it?” I said, “Yeah!” I wasn’t sure if I was heavy enough to work with his guys – he told me that if I was willing to work hard I could do it. So like a good father, he took me in.

What do you think is the most common misconception that people have about Frank Zappa?

I don’t know anything about brain surgery, right? When neurosurgeons start talking shop I’m lost, and I don’t really care. I care that they’re helping people. To really understand a musician or another human being, you’ve got to live it, be it and have something in common. I don’t think rock journalists have much in common with a guy like Frank. He probably had at least seven talents and could have made a successful career out of any one of them. He was 10 years older than me and a real genius on all those levels.

I came to him so naive. Every negative thing he said about the music business or politics I almost refused to believe because I couldn’t go there – I couldn’t lose hope, you know what I mean? But everything he said has come to pass. Everything he ever said, as cynical as it was, was true. He was really one of these guys who was like an arrow. He could cut through anything, get right to the heart of it and sum it up in the most succinct way.

Frank told Don Van Vliet how shocked I was at his music, and Don and I became more friendly

How did you come to leave Zappa’s band?

I’d been playing with Patrick O’Hearn, Mark Isham and Pete Maunu as Group 87 and we’d been to audition for a deal at CBS. I was late for rehearsals with Frank because of it. He sensed what had happened. We started playing something but he felt that I didn’t have the heart for it any more. He said, “Bozzio, step into my office.” We went behind the little riser in the rehearsal studio and he said, “I think it’s time to go out and do your own thing.” And once again, I said, “Are you sure I can do this?” Like a good father he kicked me out of the nest.

What’s the thing you regret the most about that period with Zappa?

That I didn’t ask questions. I didn’t want to show my ignorance. Many times he used words I didn’t understand and I’d just laugh because I didn’t want to appear stupid. I wish I’d asked what the words meant. Stuff like that. But I was young and just happy to be there, going through all the rock’n’roll, groupie bullshit. Nobody can tell you how to handle success. When it comes you’re on your own, and you just get swept along with whatever’s happening. Later, you learn through experience that it may not have been the best way to do this or that.

How would you describe the difference between Don Van Vliet in private and Captain Beefheart in public – or were they both the same?

He was just out there, man; he was his own person. When I first met him I thought he was like an acid casualty from Frank’s past. Then I got to know him a little better and realised how deep he was. He loved some rough and dirty blues that not a lot of people know about – or rather, didn’t know about then.

The big revelation came when we were in Austin, Texas, recording Bongo Fury. Frank asked me to come over to his room. He’d sent someone out to buy a portable record player and he put on Trout Mask Replica. I listened to this stuff and it was just out. I mean, completely random noises. It didn’t seem organised in any way. Frank said, “You know, they played this exactly the same way every time.” And then I went, “Oh my fucking God!”

I began to realise that on a whole other level, Beefheart was just as deep as Frank. I think Frank told Don how shocked I was at his music, and Don and I became more friendly. I got into the drawing thing and he encouraged me; that was really sweet. He’d say, “I really like the freedom of what you’ve got going on here,” and it helped me move into more abstract areas.

I have much respect for Eddie Jobson; but as people we have different ideas about how things should be

He’s still regarded as something of an enigmatic figure, isn’t he?

As a person, you need a thesaurus of mythological and symbolic and maybe even jazz bebop terminology to even understand what he was saying. He spoke in symbols, and they were very idiosyncratic symbols. It was really a journey and adventure to be around the guy.

One time, in my second year with Frank, Beefheart had finished his stint and was forming his own thing. Frank rented a suite at the Beverly Hilton hotel where there was a record company convention going on. We got into the elevator. There was Patrick O’Hearn, who’s got an amazing sense of humour; myself; Frank, who’s just on another level of being really funny; Gail, his wife, who’s really smart and capable; and there’s Beefheart.

We’re in this elevator and out comes Herb Alpert’s muzak version of A Taste Of Honey. The space in there was electric, everybody’s eyes were darting around, wondering who was going to say something first – who’s gonna rip this music? Beefheart jumps in and says, “Y’know, there’s only one kind of thing you can do with this music.” He snaps his fingers and shouts, “Dig it!”

What was the transition from Frank Zappa to UK like?

It was painful. It was depressing. I did the Group 87 record, but as a sideman – looking at the record contract was really shocking so I’d decided not to sign. A year later I think I had an audition for Thin Lizzy that didn’t come together. I’m not a drink-fight-and-fuck kind of guy. Gary Moore wanted me and we got on great, but I was not in that same headspace as the rest of those guys. So it was the right thing.

Eddie Jobson talked to me about Bill Bruford and Allan Holdsworth wanting to be more jazz, whereas John Wetton and he wanted to go more rock. So I started in UK in ’78. That was a tough transition. I was still just a sideman; I didn’t want to sign another contract where the company owns everything into perpetuity.

Eddie and John made all the decisions, and there’s always that Upstairs, Downstairs thing when you deal with the English! Eddie and I just cannot see eye to eye. He looks at it like a corporation and he’s the CEO, and I don’t feel I’m respected as somebody who contributed to what they are, and even what they can be today. I have much respect for Eddie as a composer and a musician; but as people, we have two different ideas about how things should be.

Out of all your varied bands and projects over the years, what stands out for you?

My stint with Allan Holdsworth, Tony Levin and Pat Mastelotto in 2010 under the name HoBoLeMa was one of the best experiences I ever had. I regard that band as incredibly important. Allan was playing his ass off! He’s a complete master of that instrument and he’s taken it places that nobody else has.

Louis Bellson said, ‘Don’t forget about notes and chords… it’s not just about drums.’ That stuck with me

How important is connecting with an audience in those circumstances?

There’s something about recorded music, whether video or audio, that’s nowhere near the magic that happens when real humans play music for other real humans in a room. Something is transcendent there. It just can’t be duplicated.

What’s the best advice you’ve received?

One time I met drummer Louis Bellson and he said, “Don’t forget about notes and chords; study music; learn how to play the piano - it’s not just about drums.” That stuck with me to this day.

It’s a tough environment for musicians to make a living. How do you stay optimistic?

With my work. I release my music and my art on my website, so now I can sell directly to the public. I’ve been very, very lucky and I’m grateful to have had the life experience I’ve had. I’ve never had to have a day job. I’ve been lucky to just survive and learn and try to grow from all the experiences I’ve had. I’m very blessed to have had many brushes with greatness.

Sid's feature articles and reviews have appeared in numerous publications including Prog, Classic Rock, Record Collector, Q, Mojo and Uncut. A full-time freelance writer with hundreds of sleevenotes and essays for both indie and major record labels to his credit, his book, In The Court Of King Crimson, an acclaimed biography of King Crimson, was substantially revised and expanded in 2019 to coincide with the band’s 50th Anniversary. Alongside appearances on radio and TV, he has lectured on jazz and progressive music in the UK and Europe.

A resident of Whitley Bay in north-east England, he spends far too much time posting photographs of LPs he's listening to on Twitter and Facebook.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.