A really useful guide to the music of George Harrison in 24 albums - and none are by The Beatles

An album-by-album guide to Beatle George’s greatest songs, solos, milestones and innovations

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Earlier this year, George Harrison would have turned 82. But, as is often the case, the universe had a different plan in mind, and the former Beatle left us at age 58 way back in 2001.

Despite his early exit, Harrison left behind a staggering amount of recorded music to listen to, much of which is – inarguably at this point – historically important, if not the fodder of legend.

While he was an intrinsic part of the Fab Four, here we’ve attempted to pinpoint, album by album, his greatest songs, guitar solos, guest appearances and production credits away from The Beatles’ albums.

We’ve begun the timeline at 1968, excluded anything unofficial but included his most impactful cameos. No, it’s not complete (not gonna happen!), but all the biggies (and a few smallies) are here.

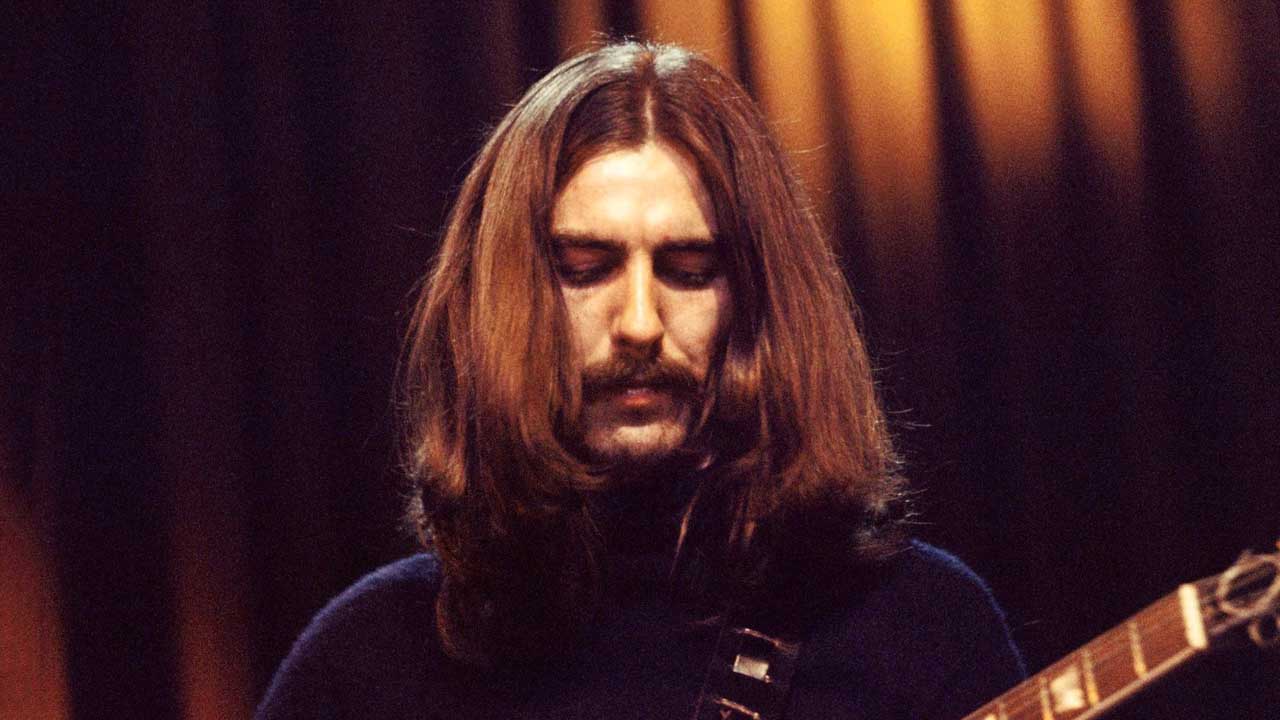

George Harrison - Wonderwall Music (1968)

You can trust Louder

This unassuming little record represents a slew of firsts. It’s George’s first solo album. It’s the first solo album to be released by any Beatle (unless you count 1967’s The Family Way, but that’s technically a McCartney/Martin project).

It’s the first album to be produced entirely by George. It’s the first time Harrison and Eric Clapton recorded together. And because it beat the White Album (more on that soon) by three weeks, it was the first album to be released via Apple Records, The Beatles’ new label. On top of all that, its title inspired Oasis’s 1995 hit, and with all its Indian music and musicians (in addition to all its Western music and musicians) it was decades ahead of the world music scene of the 80s.

But for all its firsts, Wonderwall Music is, well, underwhelming. But when you consider that it’s just an instrumental soundtrack album – for Wonderwall, an interesting little film by Joe Massot (the same gent who co-directed Led Zeppelin’s The Song Remains The Same) – you’re easily able to adjust your expectations and welcome it as a bit of ‘bonus 60s George’. Make that – on some songs – bonus 60s George plus Ringo, plus Clapton.

Unlike later big-budget soundtrack albums, there’s no hit song here – no Live And Let Die, For Your Eyes Only or My Heart Will Go On. The closest thing to a catchy, standalone tune that you might hear on SiriusXM’s The Beatles Channel is the oddly pleasing Party Seacombe. Red Lady Too is pretty cool too. DF

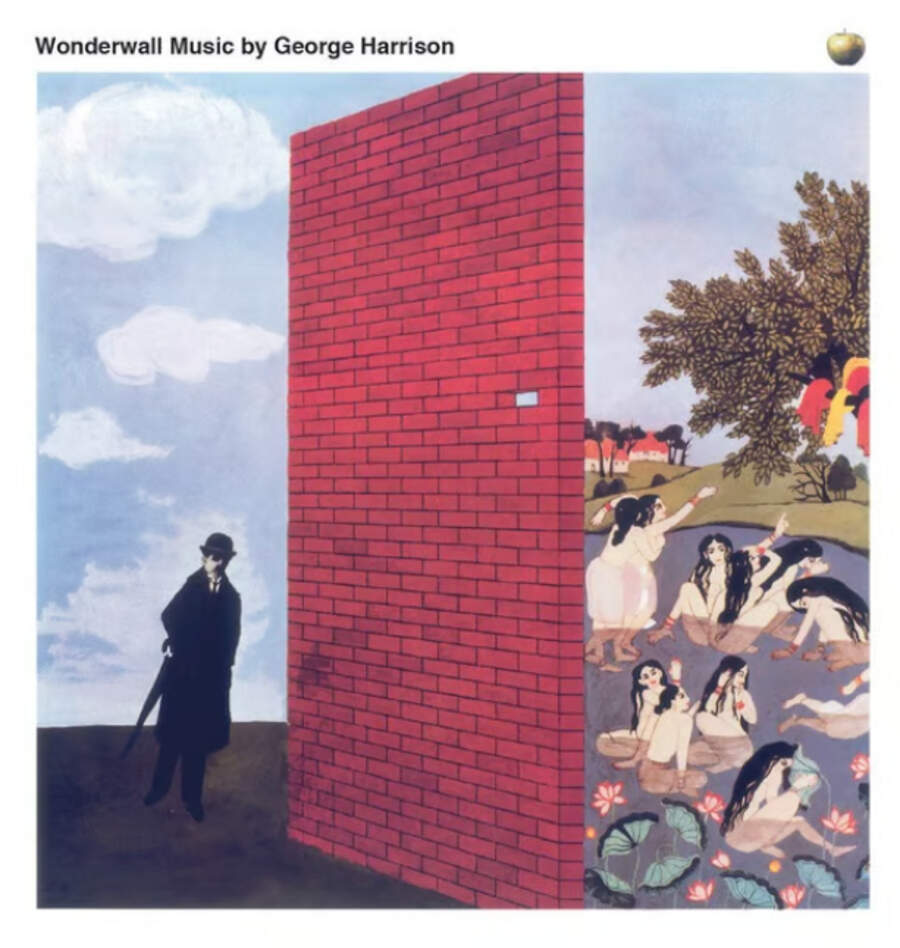

Jackie Lomax - Is This What You Want? (1969)

This brief stop in our timeline represents another rung on the ‘producer George’ ladder. Jackie Lomax, formerly of Liverpool rockers The Undertakers, had a big, booming voice and should’ve been much more famous than he was. And you’d think Harrison’s production of this Apple Records release would’ve helped a bit. It didn’t.

What’s even crazier is that the album features musical contributions by Harrison, McCartney, Starr, Clapton, Nicky Hopkins, John Barham and Klaus Voormann, not to mention members of LA’s Wrecking Crew. On top of that, lead-off single Sour Milk Sea was written by Harrison and features every Beatle besides Lennon, making it arguably more of a Beatles song than some of the stuff on the White Album and Let It Be.

Sour Milk Sea tends to get all the attention (such as it is) these days, but be sure to check out the title track (the redheaded stepchild of I Am the Walrus), and Harrison’s very out-front backing vocals on Going Back To Liverpool. DF

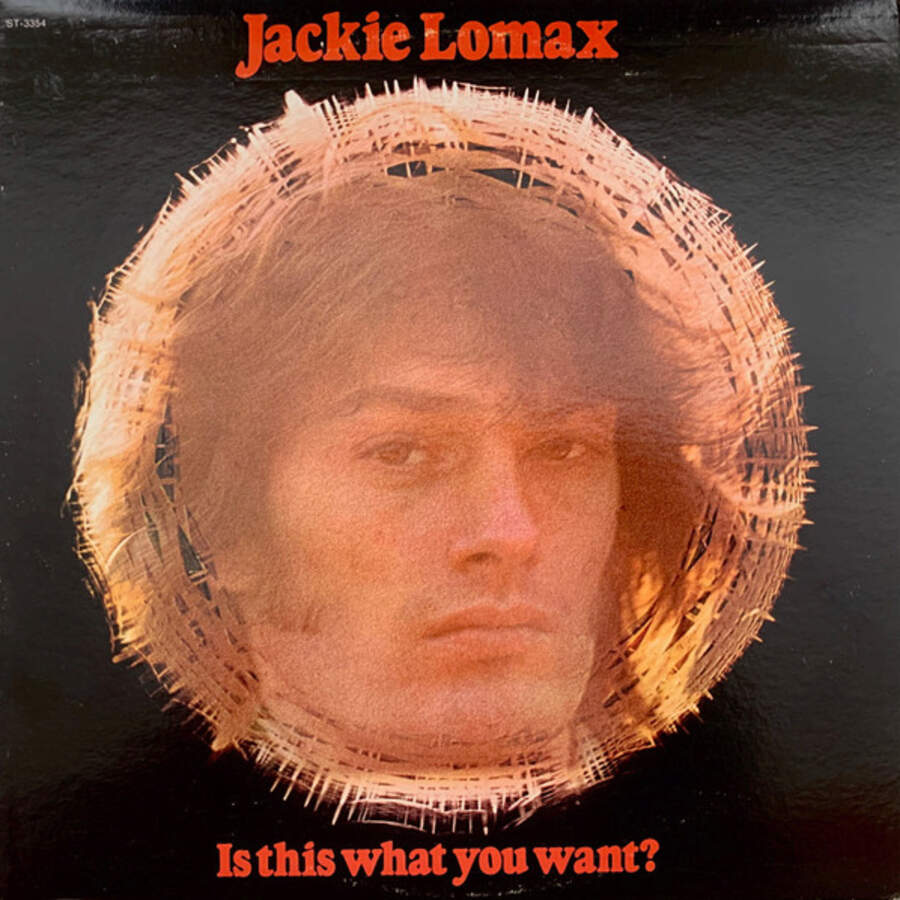

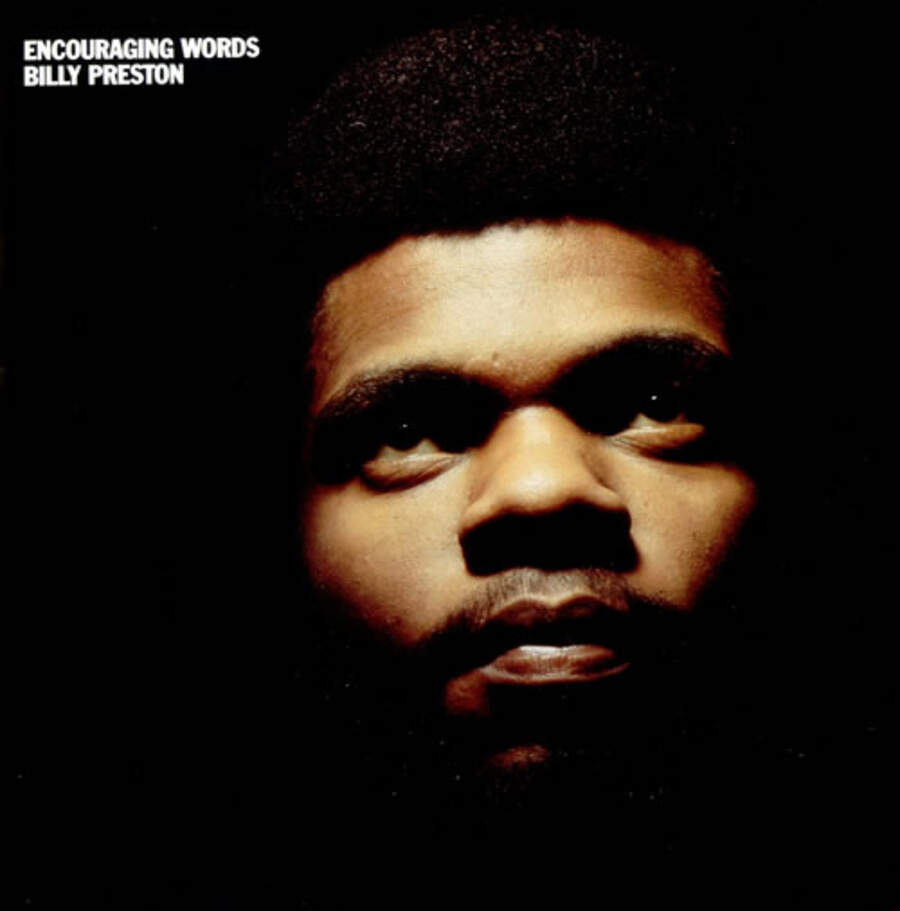

Billy Preston - Encouraging Words (1970)

From the moment Billy Preston galvanized The Beatles’ Let It Be sessions in early 1969, he and Harrison became fast friends and collaborators. Preston was all over All Things Must Pass and The Concert For Bangladesh, and Harrison co-produced and played on both of Preston’s Apple Records releases. Because the title track of his debut album That’s The Way God Planned It was a hit, that one’s better known. But this 1970 follow-up is more consistent.

Preston was a fierce keyboard player, so it makes sense that Harrison would naturally fall into more of a supporting role here. But there are standout guitar moments throughout – the fast, funky strumming and Steve Cropper-style hammered chord inversions on You’ve Been Acting Strange, the wah-wah fills laced into Use What You Got, the Leslie-swirled picking and fuzz tones on Sing One For The Lord (which George co-wrote). For more guitar power, Eric Clapton and Delaney Bramlett are also part of the all-star session crew.

If you need further proof of Harrison’s generosity as a collaborator, he gives Preston first dibs on two of his best songs from that period – My Sweet Lord and All Things Must Pass (Encouraging Words was released a full two months before All Things Must Pass). Preston takes the former straight down the aisle of a rollicking southern Baptist church, while he invests the latter with grandeur and classical flourishes. The two friends were definitely in tune musically and spiritually. BD

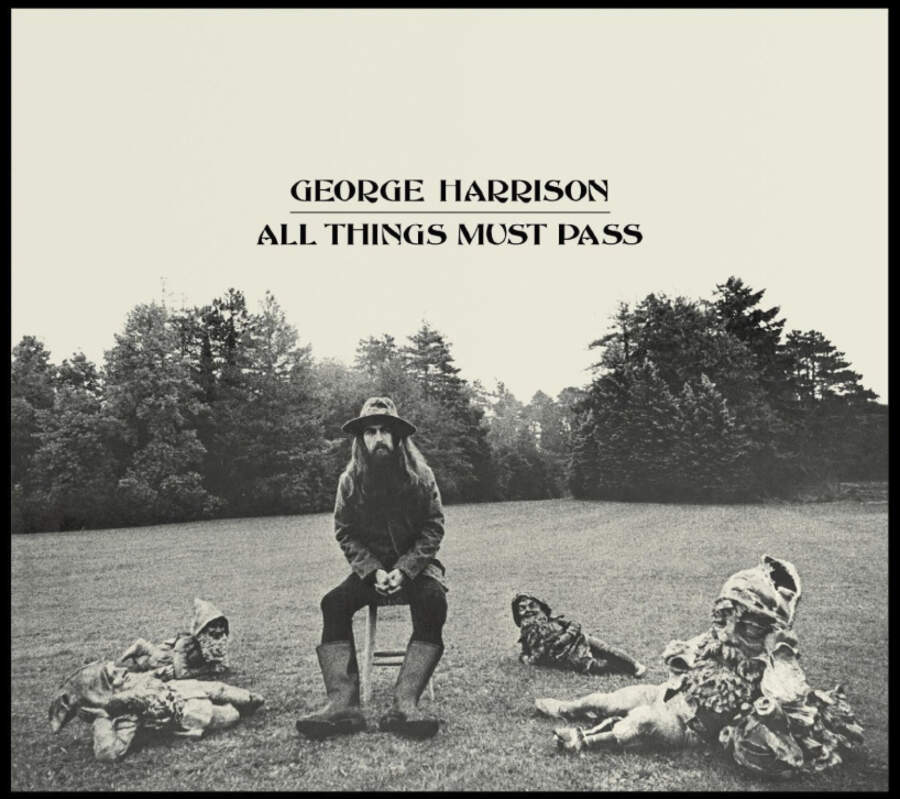

George Harrison - All Things Must Pass (1970)

Consistently constrained by his distinctly third-fiddle role in The Beatles, upon the band’s ultimate dissolution Harrison the songwriter came into his own (and then some) on this mammoth triple album. It’s packed with choice material, much of it accumulated during his latter tenure as a Beatle, and many songs had been simmering on his back burner for some years.

Isn’t It A Pity and Art Of Dying date from as far back as ’66, I’d Have You Anytime (co-written with Bob Dylan) and Let It Down stem from late ’68. An entire batch of material – All Things Must Pass, Hear Me Lord, the brash Wah-Wah – had its genesis during The Beatles’ Get Back rehearsals of early ’69.

Driven and inspired, Harrison remained prolific throughout his transmutation from Beatle to solo entity (What Is Life, Behind That Locked Door, Beware Of Darkness), but it was the album’s lead single, My Sweet Lord, that demonstrated the veritable sea change in Harrison’s approach to guitar playing.

Total immersion in studying sitar with Ravi Shankar had coincided with Harrison losing interest in the apparent possibilities of his lead instrument, but he constructed a mellifluous signature style that was to largely define the remainder of his career. IF

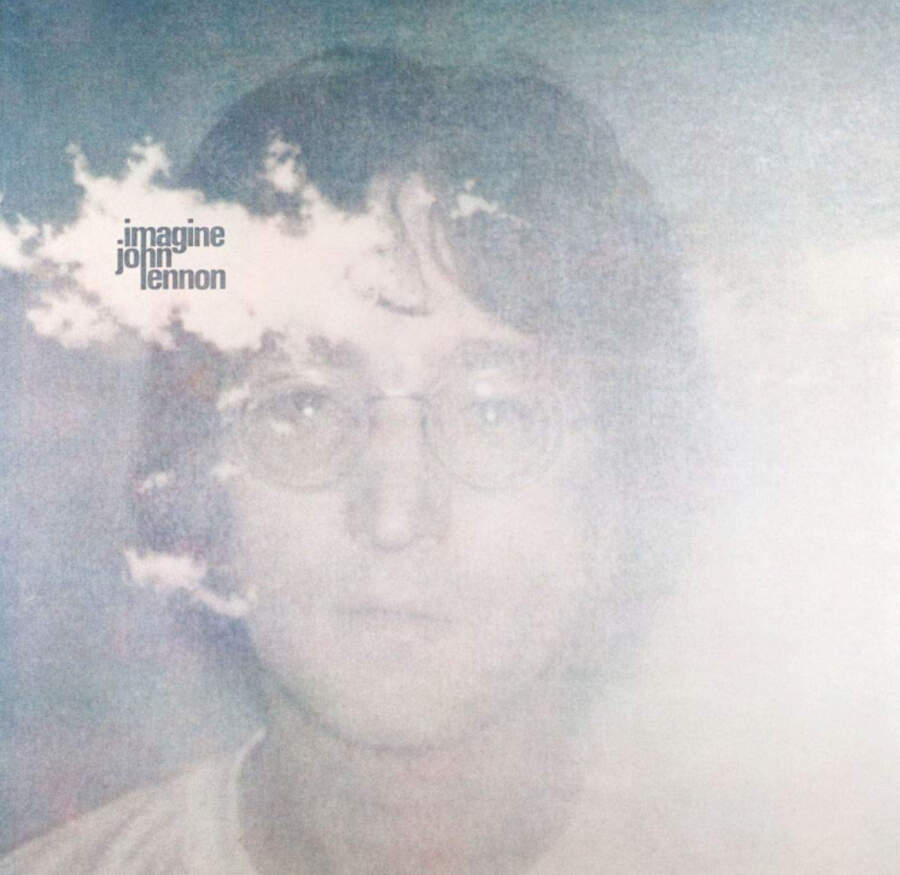

John Lennon - Imagine (1971)

Can you imagine the seeming awesomeness of long-haired, cross-legged guitar picker George Harrison’s life in the very early 70s? His songs and guitar playing could be heard on The Beatles’ Let It Be, his own All Things Must Pass and The Concert For Bangladesh (more on that soon), songs by Gary Wright (Two Faced Man), Badfinger (Day After Day), Harry Nilsson (You’re Breakin’ My Heart), Billy Preston, Doris Troy, Ronnie Spector and Ringo Starr (again, more on that soon).

Then there’s Imagine, John Lennon’s best-known (if not outright best) solo album. Harrison plays on half the album, adding brilliant slide solos to Gimme Some Truth, Crippled Inside and How Do You Sleep? and provides some sympathetic backing to I Don’t Wanna Be A Soldier and Oh My Love.

Harrison’s slide approach and tone would change over the years), but his playing on Imagine represents the high point of that make-believe thing called George Harrison On Slide, Phase 1. DF

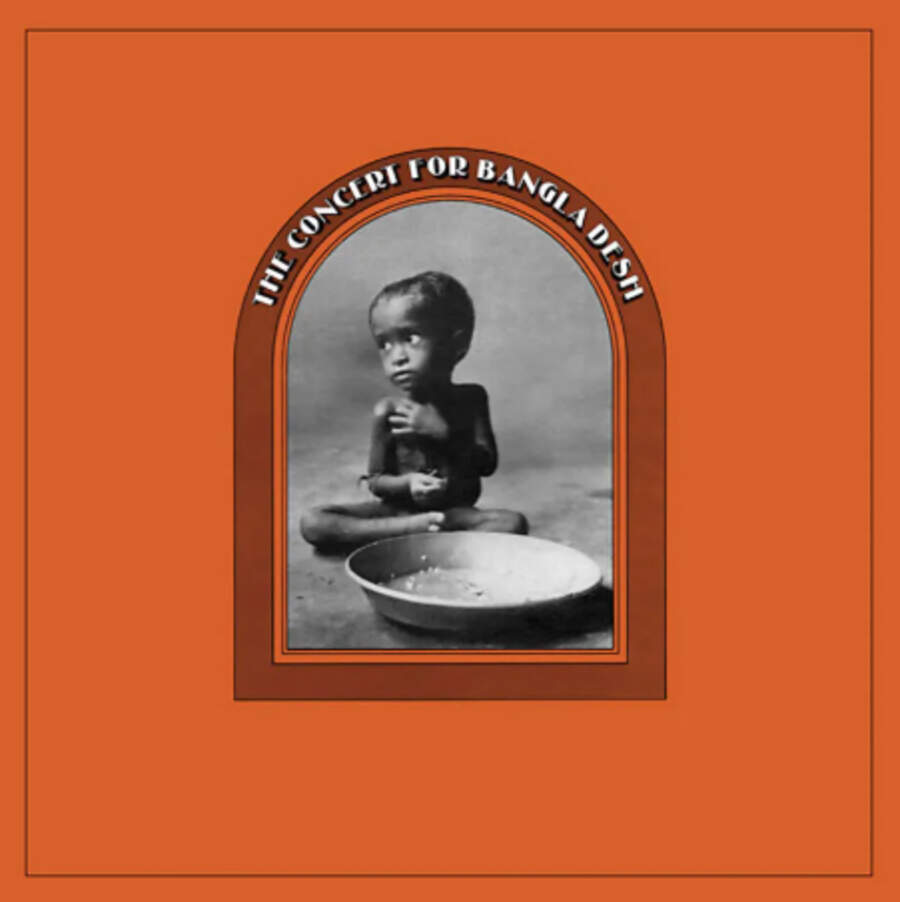

George Harrison & Friends - The Concert For Bangladesh (1971)

A year after the epic, three-disc All Things Must Pass made a wave or two, Harrison followed it up with yet another triple album, The Concert For Bangladesh, fed by two charity shows recorded on August 1, 1972.

We’re intentionally keeping the spotlight on Harrison’s studio work, but we can’t ignore this monstrosity’s many fine points, including: The first ever live recordings by a Beatle of Something, Here Comes The Sun and While My Guitar Gently Weeps. The first joint US on-stage appearance by George and Ringo since The Beatles’ Candlestick Park show in August 1966. More Ravi Shankar than you can shake a sitar at. A spirited live performance of Ringo’s Harrison-produced 1971 single It Don’t Come Easy, which features sparkling, Leslie-infused guitar playing by George.

This seems as good a time as any to mention that Harrison’s playing also graced two other Ringo tracks from this era: 1971’s Early 1970 and 1972’s Back Off Boogaloo (produced by Harrison), which arguably features one of his greatest slide solos. DF

George Harrison - Living In The Material World (1973)

Having successfully unbound himself from the creative limitations symptomatic of his former life as Beatle George, Harrison set his sights on his other ongoing obsession: the search for spiritual enlightenment. But nirvanadashing distractions uniquely associated with being an ex-Beatle weren’t that easy to shake. Throw the massively commercially and artistically successful All Things Must Pass monolith into the mix, and expectations of its vinyl successor were unhelpfully stratospheric.

The first indicator of what was to come from the most keenly anticipated album of the year was Give Me Love (Give Me Peace On Earth). Outwardly self-explanatory (George asking his Lord for guidance, with a side order of universal fraternity and – as is his usual modus operandi – some sort of indication that he’s actually there), it captures a George still searching for enlightenment and possibly a little help on the career front. ‘Help me cope with this heavy load,’ he pleads soulfully, as only a man contractually obliged to deliver yet another hit record can.

Harrison’s exhortations are again accompanied by a trademark My Sweet Lord-esque slide, plaintively mimicking human supplication. So yes, there’s God. But, being George (remember Taxman), there’s also Mammon with Sue Me, Sue You Blues bemoaning acoustically the ferociously litigious nature of ex-manager Allen Klein.

Living In The Material World itself contrasts materialism with spirituality to the dual accompaniment of A-list Western rockers (a name-checked Ringo included) and Indian classical tabla player Zakir Hussain. But the Harrison slide is probably put to use best on Don’t Let Me Wait Too Long, a no-nonsense, Brill Building-style pop song that really ought to have been a single. So did the album sell? By the truckload. IF

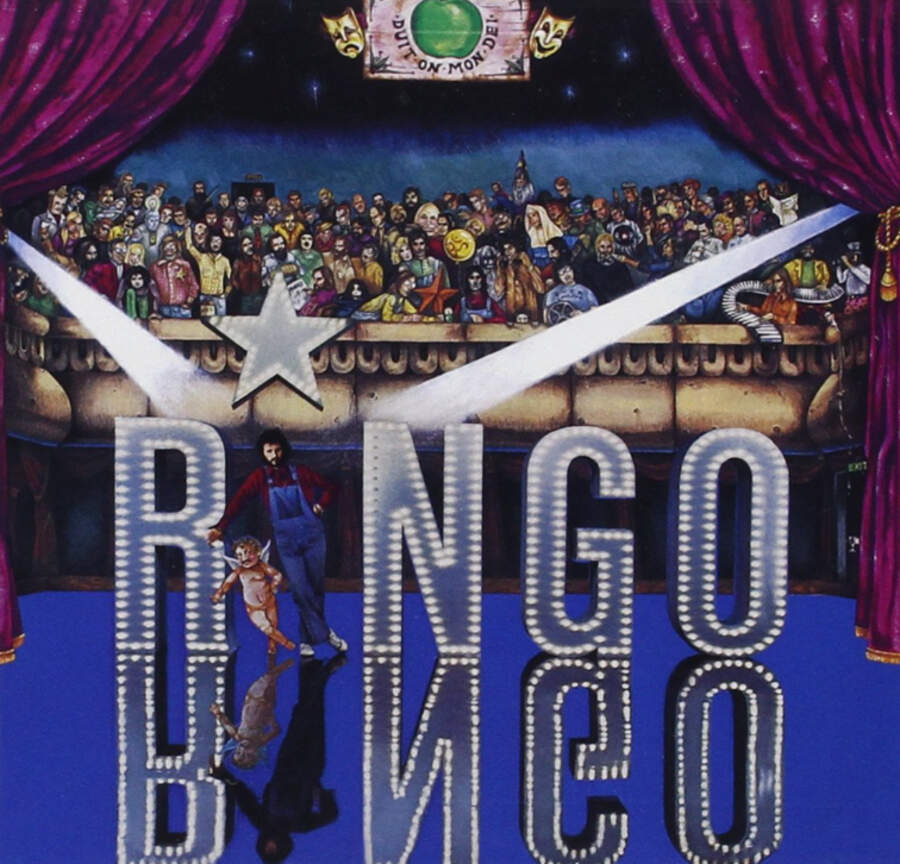

Ringo Starr - Ringo (1973)

While there was significant, widely documented acrimony behind the ultimate break-up of The Beatles, all evidence appears to suggest that no one ever managed to successfully fall out with Ringo. He’s clearly as likeable as his lugubrious public image would have us believe, and when he put out calls for assistance to the great and the good prior to recording his third solo album, they were all answered in the affirmative.

Ringo features contributions from, among others, Robbie Robertson, Levon Helm, Garth Hudson, Rick Danko and, most notably, Lennon, McCartney and Harrison. It was the first and only time all four Beatles turned out for a former band member’s solo album. Its opening track, Lennon’s I’m The Greatest, is arguably the closest The Beatles ever truly came to fully re-forming.

Harrison’s playing on I’m The Greatest recalls some of his own greatest Fab moments, from descending Help! arpeggios to sharp, Back In The U.S.S.R. rhythmic stabs; it’s as dead-on as even The Rutles could have managed.

Other standout Harrison moments include Photograph, a co-write with Starr on which he contributes up-front chiming 12-string acoustic; his Sunshine Life For Me (Sail Away Raymond), a decidedly countrified folk-rock, proto-Americana knees-up featuring David Bromberg and various members of The Band fiddling fiddles and plucking banjos as if their lives depend on it while Harrison adds Vini Poncia-abetted gang vocals and fluid picking.

Album sign-off You And Me (Babe), which(Babe) provides a sentimental coda to Ringo’s all-star bash (an M.O. he clearly warmed to, if his various subsequent All-Starr Band tours are anything to go by) that saw neat supporting flourishes – including a further series of bold attention-grabbing arpeggios and a solo that, while celestial, has no intention of overstaying its welcome – from Harrison, prior to a spokenword farewell from everybody’s favorite Liverpudlian drummer. IF

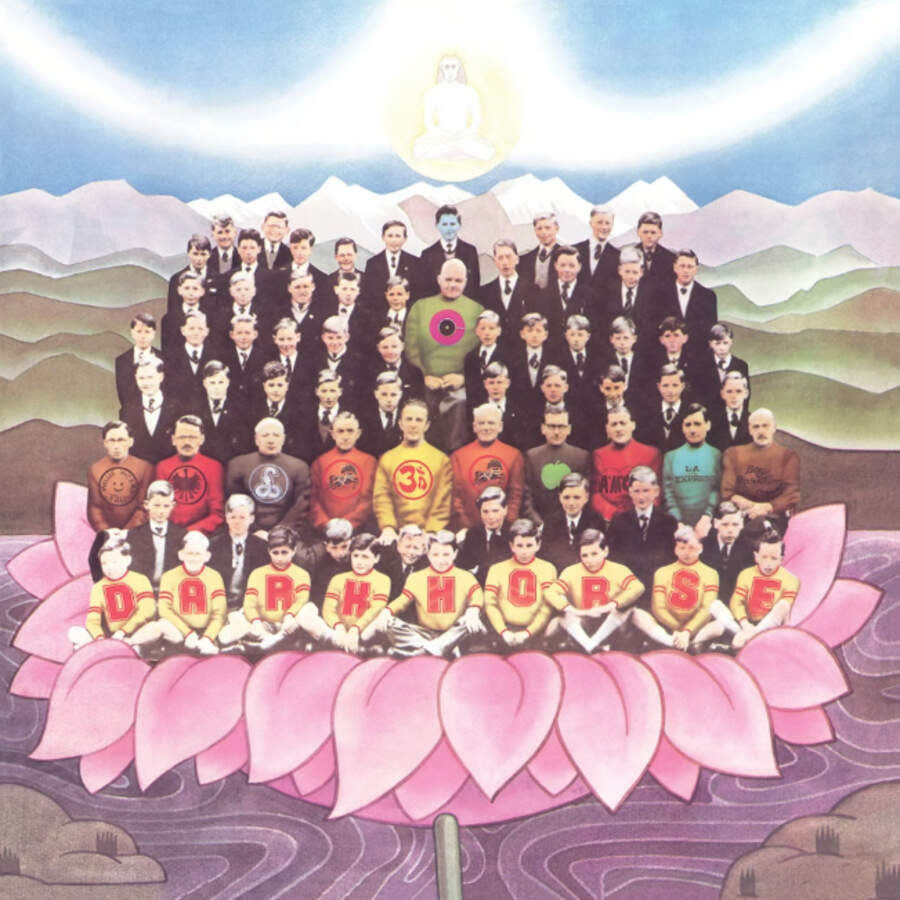

George Harrison - Dark Horse (1974)

Things weren’t great in Harrison’s life during Dark Horse’s creative process. There was the unexpected criticism levelled at Material World, his long-percolating split with first wife Pattie Boyd that had spilled over into soap opera (she conducted affairs with Eric Clapton and Ronnie Wood as George found solace in the arms of Ronnie’s wife Krissy and Ringo’s wife Maureen).

Then there was all the post-Apple, post-Klein, post-My Sweet Lord plagiarism litigation. Plus pulling together his own record label (also called Dark Horse), the drink, the drugs, and the laryngitis he contracted during the latter period of recording, which carried over into a widely anticipated, if ultimately badly received, ’74 tour with Ravi Shankar.

But misery often engenders surprisingly fertile creative ground, and Dark Horse has its moments, not least its title track. Weirdly placed near close of play, it’s an inoffensive acoustic ditty, often weighed down with academic interpretations it doesn’t really deserve. So Sad, laden with Here Comes The Sun-contrasting grey, wintry imagery, captures a post-Pattie George at his most despondent (cue lashings of lachrymose slide).

Harrison history wouldn’t be any poorer for the loss of either a largely wretched near-cover of the Everly Brothers’ Bye Bye Love or the repetitions of Ding Dong, Ding Dong, but these clangers are more than offset by Simply Shady, a wordy, distinctly Dylan-esque examination of karmic consequences, rich in stinging, country rocking guitar asides with a lead vocal that actually benefits from the short-term ravages of laryngitis, and Far East Man, a co-write with Ronnie Wood that cogitates upon the power of friendship. Dark Horse failed to make a dent in the UK album chart. IF

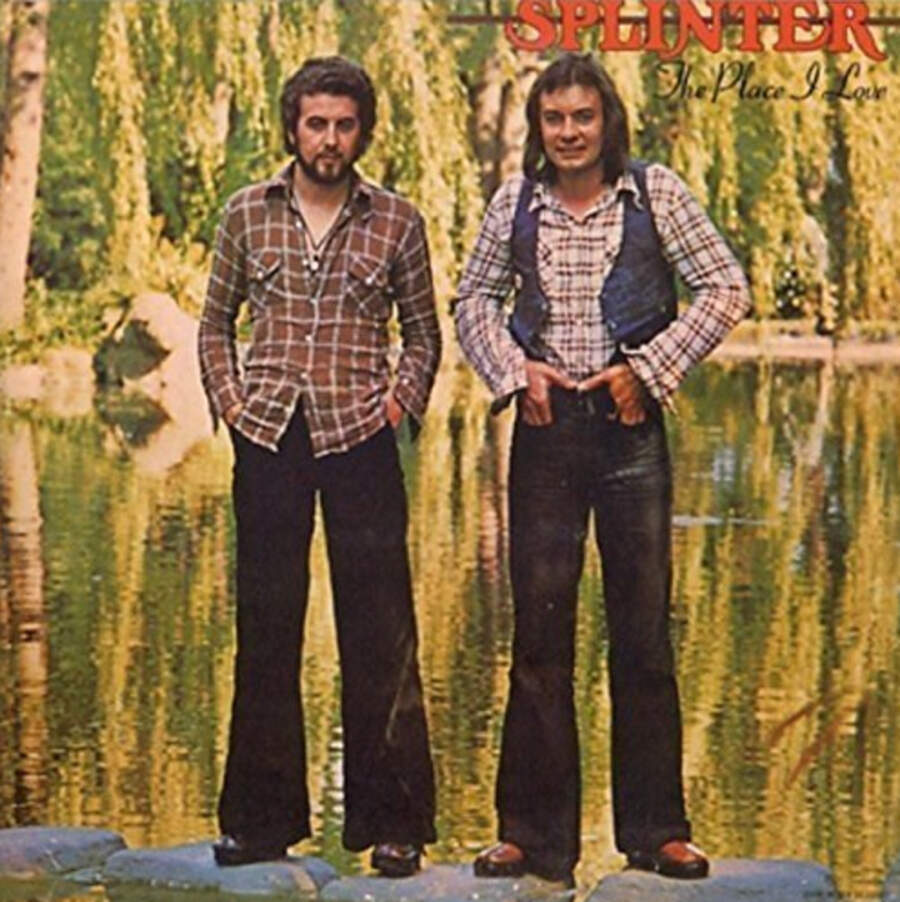

Splinter - The Place I Love (1974)

Splinter’s overlooked debut album actually came out a few months before Dark Horse, but we’ve taken some liberties here with chronology because it’s easier to explain The Place I Love in the context of Dark Horse.

Ya see, The Place I Love was actually one of the reasons Dark Horse was rushed, not to mention one of the (alleged) causes of his infamous case of laryngitis. He simply put so much of himself into the album – contributing 95 per cent of the guitars, plus bass, harmonium, percussion, mandolin, synthesiser and backing vocals; assembling the band, which features usual Harrison suspects Klaus Voormann, Willie Weeks, Billy Preston and Jim Keltner; recording it at Friar Park, his home studio; and releasing it on Dark Horse Records, his own label.

He didn’t write any of the songs, but that doesn’t mean the album isn’t full of beautiful Badfinger- and late-Beatles-esque songplay, the spine-tingling highlight of which is probably the addictive China Light. In terms of guitar, check out Somebody’s City – it’s interesting to hear Harrison employing his Strat and easily identifiable 1974 Dark Horse sound on someone else’s song. It’s the sort of thing that makes you think he could have put out a flawless album in 1974 if he somehow could have combined the best parts of The Place I Love with the best parts of Dark Horse.

Anyway, for a few more “Wait! That’s George sounding exactly like George but playing on someone else’s track!” moments, have a listen to Situation Vacation and the heart-melting slide on China Light, which – have you noticed? – we keep mentioning.

Around this same time, George also produced and played on Ravi Shankar’s Shankar Family & Friends, which only seems to support the case that in mid-74 he really was burning the candle at both ends. DF

George Harrison - Extra Texture (Read All About It) (1975)

Harrison certainly wasn’t above revisiting his invariably profitable Beatle George persona should circumstances demand it, and considering the degree to which Dark Horse had stiffed in the marketplace, demand it they did. So Harrison combined every ounce of his creative power and mercenary acumen and basically threw everything at Extra Texture, his final album for Apple.

Largely dispensing with the services of his Dark Horse band (which was built around a core of keyboard player Billy Preston, bassist Willie Weeks, drummer Andy Newmark and sax player Tom Scott), Harrison relied on David Foster, Gary Wright and Leon Russell (keyboards), Jim Keltner (drums), Jesse Ed Davis (guitar) and Hamburg chum Klaus Voormann for Extra Texture’s more commercial material.

Aside from freshening things up with a distinct whiff of Smokey Robinson-inspired soul, there’s significantly less spiritual yearning for universal karma, and a lot more trad George. Not taking any chances, lead single You was co-produced by Phil Spector, pivots on a dynamite hook and features that most simplistic of all Beatles stand-bys: a chorus that repeats the word ‘love’ until every listener succumbs to the inevitable and gets their wallet out.

Sharing its feel and message of tolerance with Isn’t It A Pity, The Answer’s At The End echoes All Things Must Pass before This Guitar (Can’t Keep From Crying) mimics While My Guitar Gently Weeps to demonstrate that the bad reviews Harrison’s ’74 tour garnered were so hurtful that even his guitar broke down. Featuring excellent guitar solos from Jesse Ed Davis, it’s the standout six-string-based element of a largely piano-centred record. It returned Harrison to the UK Top 20. Mission accomplished. IF

George Harrison - Thirty Three & 1/3 (1976)

While primarily released on a slice of vinyl that revolved at 33 1/3 revolutions per minute, Harrison’s seventh solo album was also coincident with his having attained that particular age. It also marked something of a return to form.

Ill fortune might still have dogged his days outside the studio – hepatitis set in shortly after recording commenced, and during production his My Sweet Lord case was ultimately found in favour of the plaintiff – but, backed by a watertight band, his artistic output suffered no ill effects. Urban country/funk-fuelled opener Woman Don’t You Cry For Me, with its roots that date back as far as Harrison’s ’69 slide epiphany, is a stormer. It perfectly suits its soul-centred ’76 zeitgeist, Harrison’s slide tessellating perfectly with Willie Weeks’s slapped bass, Alvin Taylor’s tight-but-loose drums and David Foster’s driving, post-Superstition clavinet.

Dear One is a light (Hindu monk/yogi/guru) Paramahansa Yogananda-inspired near-solo ditty perked up significantly by Richard Tees’s keyboards. This Song, written following a week in court trying to convince a New York City judge that his My Sweet Lord wasn’t a mere cynical rip-off of The Chiffons’ He’s So Fine, is defined by its bittersweet, plagiarism-based lyric, but it’s Billy Preston’s piano and Tom Scott’s sax solo that elevate it into the arena of the excellent.

Harrison was never more comfortable than as a member of a band, be it as a Beatle or a Traveling Wilbury, and on high-calibre compositions like See Yourself, the Eric Idle-sparked surrealism of Crackerbox Palace and It’s What You Value, the Thirty Three & 1/3 studio band sounds like a solid working unit rather than a cast of sessioneers putting in the hours. IF

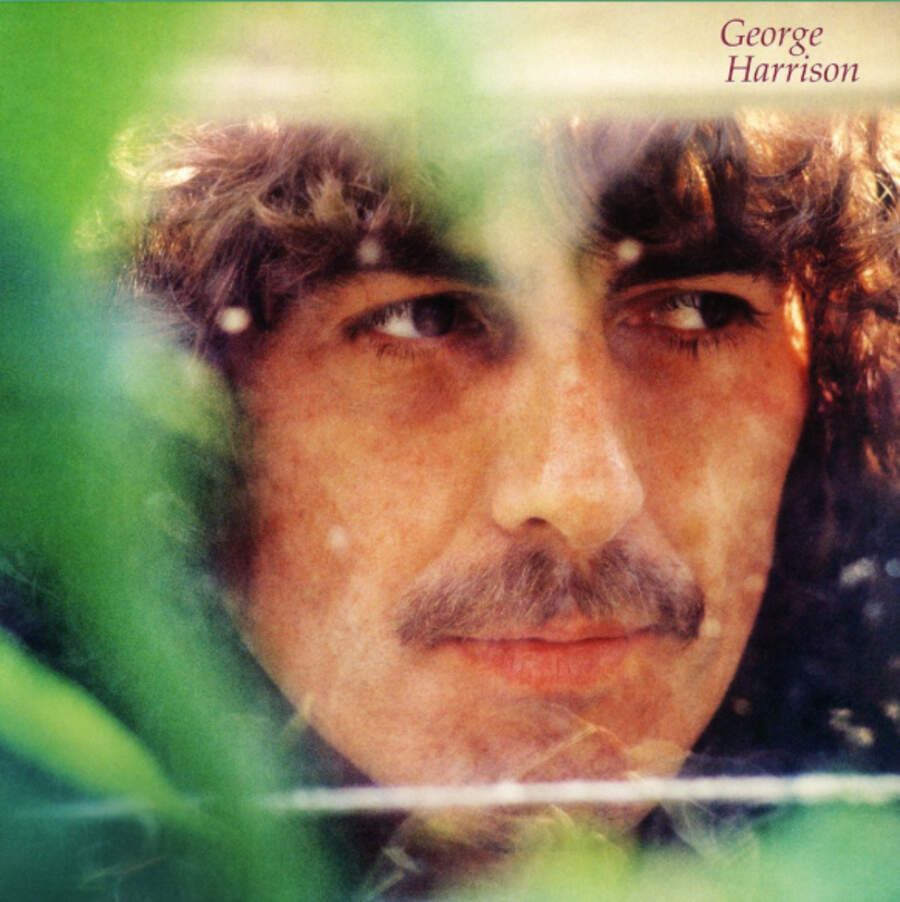

George Harrison - George Harrison (1979)

‘Sky cleared up, day turned bright,’ an unusually optimistic Harrison sings on Blow Away, the first single from a self-titled album that garnered unanimous critical approval. George was evidently in the pink; he’d married Olivia Arias and become a first-time father, to Dhani, during the album’s gestation. Consequently, while contemporary opinion likened George Harrison positively to his All Things Must Pass solo zenith, it offered little darkness of which to beware.

Shot through with infectious optimism and featuring a politely insistent hook, a signature guitar intro from Eric Clapton and Stevie Winwood on synth (and backing vocals), Love Comes To Everyone (covered by Clapton and Winwood in 2005) is a portent of the mega-commercial, coffee-table-smooth rock that came to dominate the coming decade.

Not Guilty, written in ’68 to debunk unfounded accusations thrown at the Maharishi by George’s fellow frontline Beatles, and previously recorded during the fraught sessions for The Beatles’ White Album (it’s available on Anthology 3), takes on a keyboards-driven (Winwood again, with Neil Larsen) featherlight jazz inflection.

Here Comes The Moon, Soft-Hearted Hana and Your Love Is Forever boast McCartney levels of likeability, but it’s Blow Away – with its ample portions of inimitable slide and Beatles-era cheeriness – and a Phil Spector-mimicking Gary Wright co-write If You Believe (oddly reminiscent of contemporary ELO) that truly set a seal on the album’s well-deserved reputation as a mid-career Harrison essential. That, again somewhat bafflingly, managed to garner only relatively modest chart action.

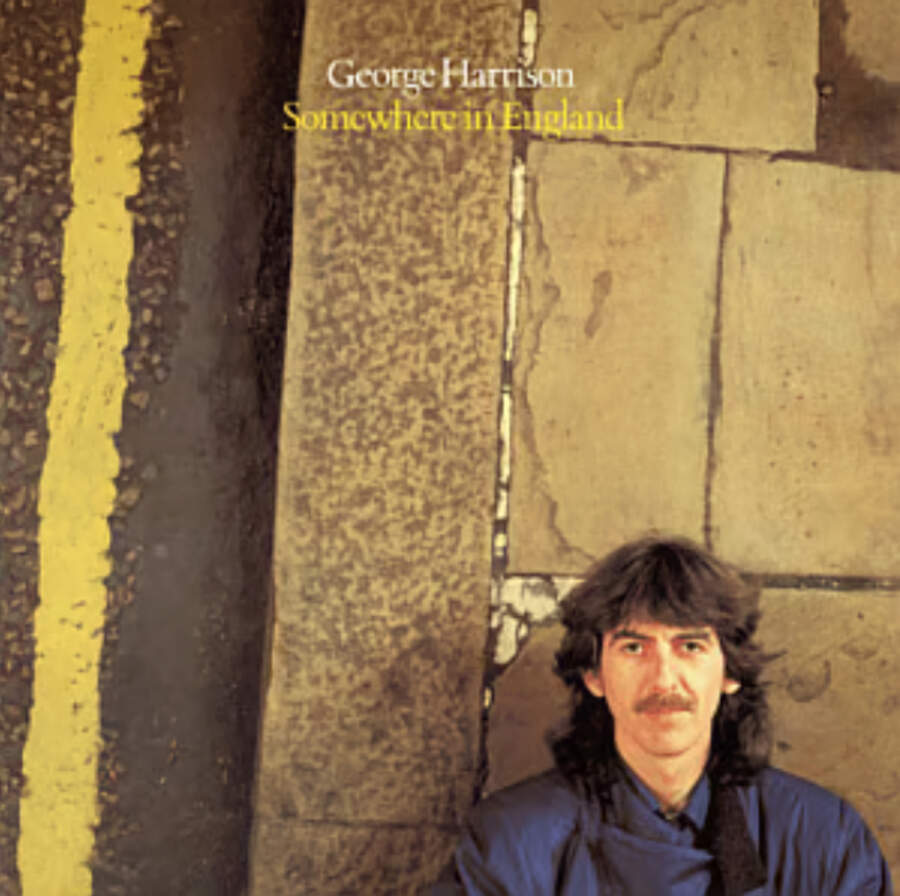

George Harrison - Somewhere In England (1981)

After 1970’s invocation of My Sweet Lord, Harrison never really stopped praying on his albums. Sometimes it was in the background. But when it found its way to the foreground, as on Life Itself, the standout track on Somewhere In England, it could make even an atheist feel devout. With its circular chord progression and gospel-like melody, the song yearns upward. And Harrison’s slide guitar acts as a second voice, answering his lead with a sympathetic ache.

Harrison needed prayer power in 1981. He was at odds not only with a changing music scene, but also label Warner Bros, who rejected the first version of the album as “too laid back” (Blood From A Clone was Harrison’s bitter riposte). It was only when he tweaked lyrically the already recorded All Those Years Ago to be a tribute to recently deceased John Lennon that they heard a hit. It is a hooky tune, and features Ringo and Paul (not to mention Wings’ Linda McCartney and Denny Laine), but what remains puzzling is that after the ultra-tasteful slide licks throughout, Harrison then forfeits the solo to that wonky synthesiser. Surely it deserves a Beatle-esque guitar break.

More satisfying is the rockabilly pluck of That Which I Have Lost and Save The World. Of Harrison’s solo albums, this one sounds the most dated and distant. That’s due to the excessive use of chorus effects, perfunctory songwriting and the inclusion of musty covers Baltimore Oriole and Hong Kong Blues. BD

George Harrison - Gone Troppo (1982)

‘They say I’m not what I used to be/All the same I’m happier than a willow tree,’ Harrison sings on Mystical One. In that one couplet, he addresses the two most common criticisms of this, his tenth studio album, which are that it’s his worst (it’s definitely not), and it’s his happiest (well, why begrudge the once-melancholy Beatle a breezy moment?).

If there’s anything detrimental on this record, it’s the sequence. The weaker material – the island-flavoured Wake Up My Love, the silly 50s doo-wopper I Really Love You – makes Side One feel slight. It’s rescued somewhat by the mostly instrumental Greece, with Harrison’s subtle gathering of volume swells, bell-like harmonics and dual slides rendering a dappled postcard.

The much weightier Side Two reminds us of how singular his songwriting could be. Mystical One features those deft, major-to-minor harmonic shifts that are instant George. Album standout Unknown Delight, an ode to his wife Olivia, feels like a sequel to Something – Harrison even briefly quotes a figure from it in his exquisite, shivery solo.

Circles, a meditative tune written in India in ’68, is rescued from oblivion and given a synth-heavy treatment; hey, at least those synths were played by Deep Purple’s mighty Jon Lord. And let’s not forget that the whimsically catchy Dream Away was both the theme song for Terry Gilliam’s film Time Bandits and a prescription for creativity. ‘Measure the mystery and astound,’ George sings. BD

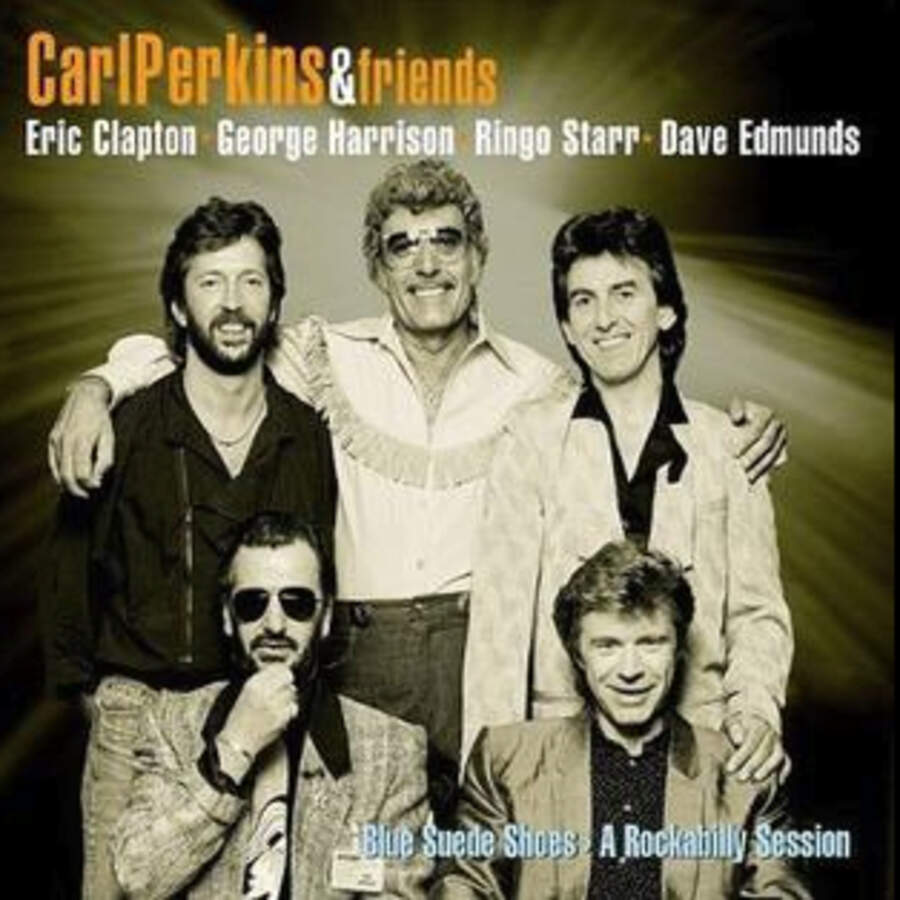

Carl Perkins & Friends - Blue Suede Shoes: A Rockabilly Session (1986)

Rock’n’roll pioneer Carl Perkins did a fine job when assembling the talent for the televised October 1985 concert that was meant to showcase his classic 50s tunes, many of which were covered by The Beatles. You had your Clapton, your Dave Edmunds, your Ringo and your Rosanne Cash. But Perkins’s biggest get was George Harrison, who was practically a recluse at that point. So Perkins was technically the star of the show, but Harrison was – you know what I’m sayin’ here – the star of the show.

Playing a late-1959 Gretsch 6120 – with delay so thick and friendly that Cliff Gallup and Brian Setzer were probably salivating – George bopped his way through Everybody’s Trying To Be My Baby, which The Beatles recorded for Beatles For Sale. Your True Love, which The Beatles tackled during the Get Back sessions, is another winner.

Also around this time, Harrison’s otherwise lost cover of Bob Dylan’s I Don’t Want To Do It appeared on the soundtrack to Porky’s Revenge. Two mixes were released, one of which highlights Jimmie Vaughan on guitar.

“[Harrison] was great,” Vaughan said in 2011. “We were trying to be cool, like, I wanted to go ask him all these questions. I asked a couple, and then I kind of shut up because I didn’t want to be just another guy pestering him.”

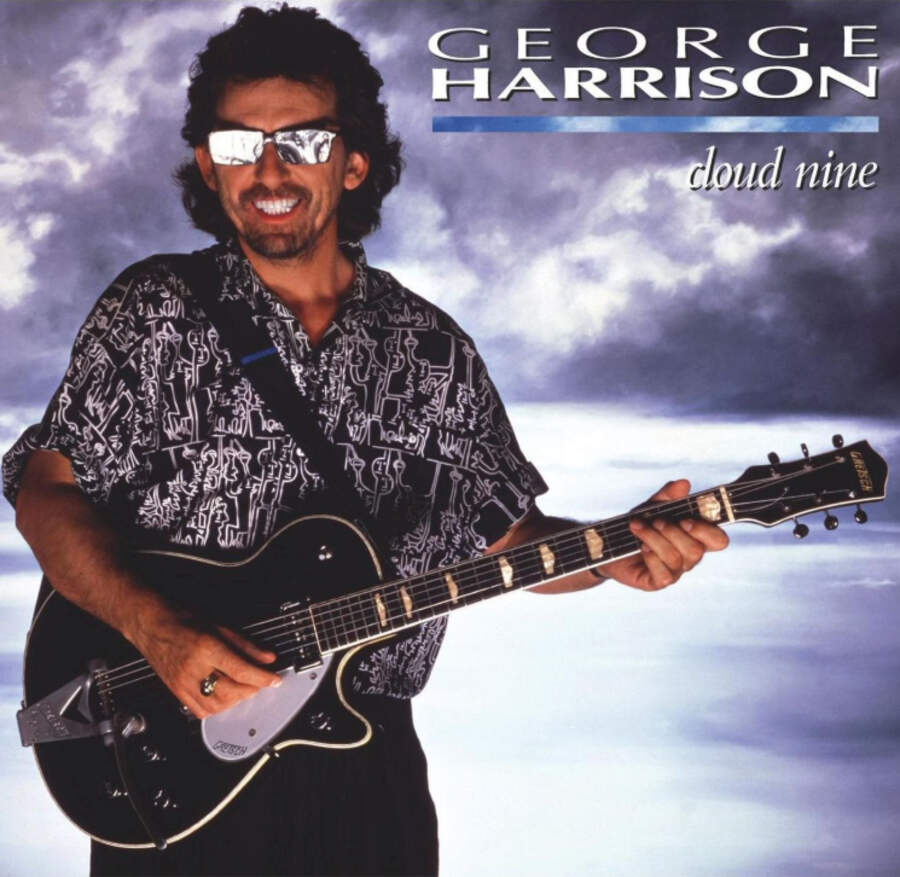

George Harrison - Cloud Nine (1987)

In 1974, when John Lennon was a guest DJ on WNEW in New York City, one of the records he played was ELO’s Showdown. In a bit of cosmic foreshadowing, he said: “I call them Son Of Beatles.” Lennon didn’t live long enough to see that son grow up to become an honorary Beatle; ELO main man Jeff Lynne would produce John’s fleshed-out demos-turned-Beatles tracks Free As A Bird and Real Love.

But it was Cloud Nine, Harrison’s eleventh album, where Lynne first entered the story. George was coming off a five-year hiatus, and he hired Lynne, who, amazingly, he’d never met, as his creative co-pilot (“It’s handy to have someone to bounce ideas off of,” he said). It was a smart move. Harrison sounded refreshed, he had his first hit album in more than a decade, and Got My Mind Set On You and the Beatles pastiche When We Was Fab were all over the radio and MTV.

But there was a trade-off. Any artist who works with Lynne – such as Dave Edmunds, Ringo Starr or Bryan Adams – can end up sounding more like ELO than like themselves. And Lynne’s sonic fingerprints are all over this record – the arid, bluesy Cloud 9, the celestial synths and Xanadu-like churn of This Is Love, the lush vocal stacks on Devil’s Radio. The ELO-ness can be very distracting, so much so that sometimes on this record it even overpowers the presence of starry guests Ringo, Clapton and Elton John.

What’s more difficult to explain is how Lynne’s entrance marked a shift in George’s guitar playing. The previous decade and a half’s lyrical solos, the honeyed dual slide harmonies, started to give way to a leaner, bluesier approach In a career that saw him undergo much stylistic evolution – from rockabilly picking to Indian sitar to psychedelic fuzz to lyrical slide – it’s still a mark of Harrison’s touch that the variation that began on Cloud Nine is immediately identifiable as him. BD

Traveling Wilburys - Traveling Wilburys Vol. 1 (1988)

In early 1988, Warner Bros asked Harrison to come up with a B-side for This Is Love, a single from Cloud Nine. At the time, he and Jeff Lynne were hanging out with Tom Petty and Roy Orbison at Bob Dylan’s studio in LA. So as long as he was surrounded by his pals, George thought why not enlist their help. They wrote and recorded Handle With Care in a day. Harrison knew it was too good to be a B-side. “The only thing I could think of was to do another nine and make an album,” he said. So they did.

Written and recorded in just 10 days, The Traveling Wilburys Vol. 1 captures an infectious live energy – friends having fun. Of course, with such distinctive singers, the emphasis naturally stays on the songs and the vocal round robins. But amid the lush acoustic strumming from all five, George steps out with a few tasteful lead moments – the Carl Perkins-style rockabilly licks on Rattled; the fuzzed, bleating slide on Margarita; the plaintive melodic twang on Congratulations.

‘Supergroup’ is a word that gets overused these days, and sometimes is a misnomer. And often there’s a calculated impulse behind their formation. Traveling Wilburys remain the most organic and musically joyous supergroup of them all (each member of the band even adopted a cheeky fake name).

“If we had tried to plan it, or said: ‘Let’s get this band with these people in it,’ it would’ve never happened,” Harrison said. “The thing happened just by magic.” BD

George Harrison - Best Of Dark Horse 1976-1989 (1989)

A greatest-hits compilation assembled by the artist instead of the label, Best Of Dark Horse 1976-1989 includes familiar hits plus deeper cuts such as Here Comes The Moon and That’s the Way It Goes. But the real attraction is the inclusion of three new tracks.

Poor Little Girl, with its catchy call-and-response chorus and pizzicato strings, is cut from the same cloth as Cloud Nine – George-meets-ELO. The minor-key Cockamamie Business is a takedown of showbiz corporate corruption (‘Didn’t want to be a star, just wanted to play guitar’).

And then there’s the real jewel, Cheer Down (which first appeared on the Lethal Weapon 2 soundtrack). Co-written with Tom Petty, it shares a groove with I Won’t Back Down and pays tribute to Wilburys bandmate Roy Orbison with its swooping melodicism. In the final minute and a half, George cuts loose with a slide solo that folds in everything from early rock’n’roll double stops to Indian raga-style licks. The track is a tour-de-force and one of his all-time best guitar moments. BD

Traveling Wilburys - Traveling Wilburys Vol. 3 (1990)

Two months after the first Travelin Wilburys album was released, Roy Orbison died from a heart attack, at the age of 52. As a way to say things couldn’t be the same without him, the remaining members changed their nicknames and wrote a tribute to their departed ‘Lefty’ in the shape of You Take My Breath Away.

This sequel (for various reasons there was no Volume 2) favours rockabilly romps, like She’s My Baby, Where Were You Last Night? and Wilbury Twist. George gets some tasty licks in on Poor House, where his slide mimics a pedal steel, the 12-string chime of The Devil’s Been Busy, and New Blue Moon with its harmony slide echoing My Sweet Lord.

It’s not as winning as Volume 1, but 35 years on it’s difficult to disagree with Lynne’s assessment: “All these amazing characters in the wild, shouting words and writing them down, strumming a few chords. It’s a rare experience.” BD

George Harrison - Live In Japan (1992)

In late 1991, Harrison hitched a ride to Japan with Eric Clapton and his band, including guitarist Andy Fairweather Low and bassist Nathan East, resulting in Harrison’s first tour since 1974 – and his only live album besides The Concert For Bangladesh, which is more of a George Harrison & Friends thing anyway. We said earlier that we’re here to talk about the studio albums; however, we simply can’t ignore the following:

It has Harrison’s only official live performances of a slew of Beatles-era Harrisongs, including I Want To Tell You, If I Needed Someone and Old Brown Shoe. If you want to hear George playing slide guitar in a live situation, look no further. And we mean that literally; this is it – the only officially released live album featuring George Harrison on slide guitar. At least he made it count; check out Cloud 9 and Cheer Down.

That said, Harrison actually hired Fairweather Low to play some of the tour’s more intricate slide parts, which isn’t too difficult to fathom since Harrison was in frontman mode for most of the set.

“Though I don’t play slide and never did, I knew this was a life-changing moment – one of those moments where everything’s going to change if it happens,” Fairweather Low said last year. “I thought: ‘Well, I’m either going to turn up at the rehearsal and they’re going to realise I’m an absolute no-go, or I can phone George and own up.” Let’s just say it turned out just fine.

Is the one on this record the ultimate version of While My Guitar Gently Weeps? From a regular person’s point of view, no it isn’t; you’ll want to stick with the track on The Beatles’ White Album. But from the point of view of someone who thinks Harrison – and not Clapton – should’ve played the solo in the first place, yes indeed. While the Bangladesh version features some decent interplay between Clapton and Harrison, it’s kinda messy. Twenty years later, they nailed it. DF

Alvin Lee - Nineteen Ninety-Four (1994)

Harrison teamed up with his Thames Valley neighbour, former Ten Years After guitarist Alvin Lee, a few times (Lee plays on Harrison’s Ding Dong, Ding Dong and Splinter’s Gravy Train and Haven’t Got Time; Harrison plays on Lee’s On The Road To Freedom), but their mid-90s hookup takes the guitar-shaped cake.

First there’s the bizarrely delicious few seconds of Harrison playing slide on the intro to John Lennon’s bluesy Abbey Road standout I Want You (She’s So Heavy). Then there’s The Bluest Blues, which is hands-down one of Harrison’s best, most emotional slide guitar performances. As Guitar World magazine wrote in 2017: “It’s a little crazy to hear Harrison playing blues slide guitar, but there it is. In his solo, which starts at 2:15, the former Beatle plays several throaty passages that recall his wicked playing on Lennon’s How Do You Sleep?” DF

George Harrison - Brainwashed (2002)

The first thing you hear on this record is George saying: “Give me plenty of that guitar.” And, sure enough, this is a round-up of his bountiful gifts as a player, from beautifully layered and precise rhythm feels (Any Road) and rockabilly-style licks (Vatican Blues) to lyrical slide playing (Stuck Inside A Cloud) and Indian-influenced meditations (the exquisite, Grammy-winning Marwa Blues).

Released a year after he passed away in 2001, his final album included songs that stretched back over a personally challenging decade. Harrison endured financial problems and court cases (over his production company HandMade Films), three different cancer diagnoses and courses of treatments and, horrifically, an attempted murder by an intruder who broke into his home. Through it all, this project was a place of calm and sanity to which he returned.

Toward the end of the 90s, his health declining, Harrison realised he might not live to see its completion. So he left extensive – and poetic – notes for his son Dhani and Jeff Lynne to finish it. “Sort out middle of Brainwashed; cut down yew trees at back of lodge,” went a typical entry. With that in mind, the pair worked during the year after he passed to provide what Dhani called “a cradle for George’s voice and guitar”.

That sensitive approach keeps the focus on the songs, which encompass all the many sides of George – Buddhist, cosmic consciousness traveller, black-humoured curmudgeon, gardener, guitarist, former Beatle – while he considers this world and the next. As he sings on Rising Sun: ‘Until the ghost of memory trapped in my body, mind, came out of hiding to become alive.’ Another way of saying George is for ever. BD

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Classic Rock’s Reviews Editor for the last 20 years, Ian stapled his first fanzine in 1977. Since misspending his youth by way of ‘research’ his work has also appeared in such publications as Metal Hammer, Prog, NME, Uncut, Kerrang!, VOX, The Face, The Guardian, Total Guitar, Guitarist, Electronic Sound, Record Collector and across the internet. Permanently buried under mountains of recorded media, ears ringing from a lifetime of gigs, he enjoys nothing more than recreationally throttling a guitar and following a baptism of punk fire has played in bands for 45 years, releasing recordings via Esoteric Antenna and Cleopatra Records.