Creativity and the art of bass liberation. How Stanley Clarke made Up...

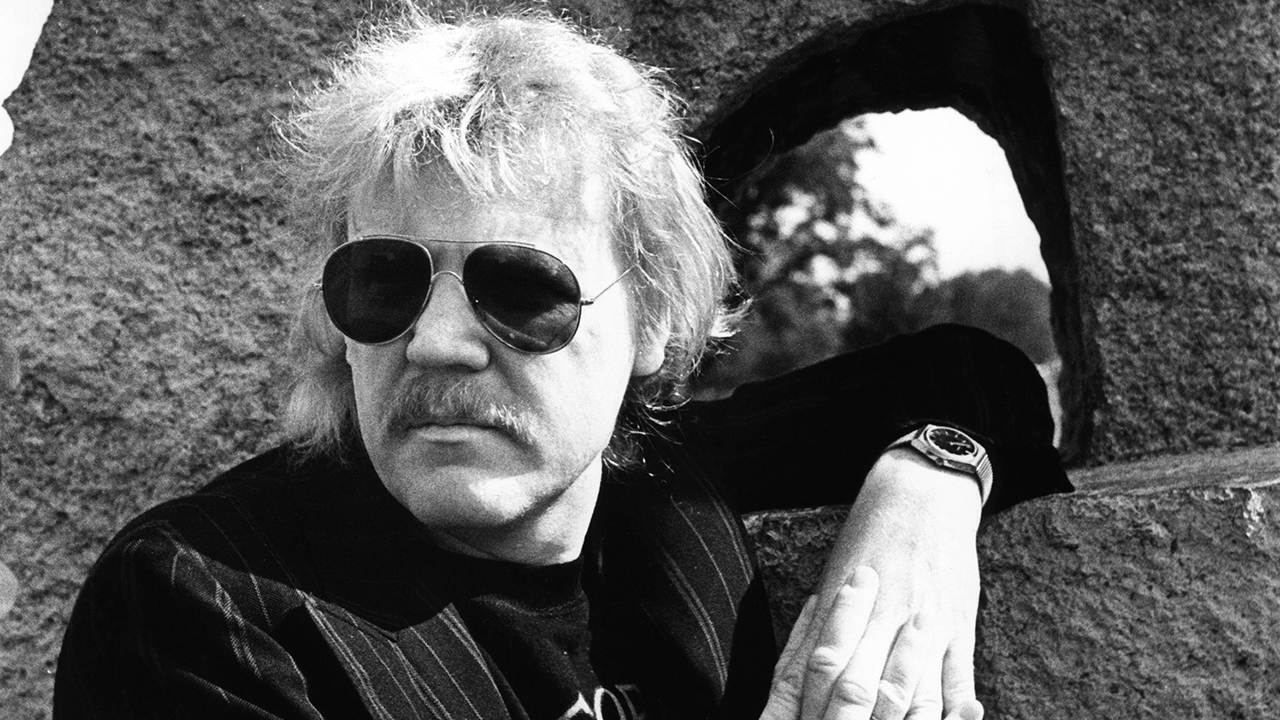

On 2014's Up, the ever-innovative Stanley Clarke nodded to his past while continuing to explore the outer reaches of bass, in another love letter to the instrument

Stanley Clarke likes to use the phrase “bass liberation”. Liberating the bass is pretty much his thing.

Breaking through in the 70s, he redefined what the previously much-neglected instrument could do, what vocabulary it could work with, where it could go and how it was perceived. After Clarke had schooled that decade, bass players didn’t necessarily have to stand at the back, avoiding attention and looking humble.

Sure, that was still an option, but Clarke had torn up the rulebook and taught us that the bass had the right to take up space in your face – especially if you could play as divinely as he could.

Weaving between genres ever since, he’s driven the golden phase of jazz fusion and a variety of other vehicles with his wonderfully fluid hooks, snaps, slaps and rotations.

“The way I view so-called genres of music,” says Clarke, up with the lark in Los Angeles, “it’s pretty much all the same, just spoken in different languages. I don’t know if other people think that, but I view playing any form of music as finding a way in, a way to do what I do. Y’know, bebop music has a certain language, created by Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie and the way that they played.

"Blues – that’s a language. Southern Rock – another language. African music, another. For some reason, when I go into these different genres, the necessary information and the language comes to me. Sometimes I’ll mix it all up, mix it together. See, if you use the word ‘progressive’ properly, it’s about stretching boundaries, about stepping outside yourself and inviting something else to happen.

“The beautiful thing is that music is the highest form of communication. One of my favourite players I ever played with is Jeff Beck: he has this sensitivity, he plays melody like few others can on guitar. Then at the same time, I love to play with George Benson. And I really, really enjoyed playing with John McLaughlin, and with Carlos Santana.

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

“These are four completely different guitarists, seriously different, but when I played with any of them, the language we were meant to speak together came forth. Because I’m playing with someone who’s progressive in their thinking, meaning that they understand what they do but they’re also interested in someone else showing them something musically. Thus genres mix and all kinds of things happen.

“Music and art – there’s no higher communication than that. It transcends words. I wish some of the popular musicians would open their minds. Once they get big, get to a certain point, they could try so much more. But so many of them play safe, stay stuck. Then they fade away, then wonder why they faded away.

“People want to find and experience new things. Once they trust you, even if it’s ‘difficult’ music, they’ll figure it out. Everyone is capable of getting to love fresh ideas.”

At 63, Stanley Clarke has over 40 solo albums to his name, as well as his breakthrough exploratory work with Return To Forever and a range of collaborations with everyone from Art Blakey to Quincy Jones, Paul McCartney to Keith Richards and Stevie Wonder to Aretha Franklin.

Over a 45-year career, he’s opened up what a bass player can do, and can be. Multiple gold records tell but a fraction of the story. When Philadelphia-born Clarke came along, most bassists outside of jazz kept it simple and maintained a low profile. With Chick Corea and Al Di Meola in Return To Forever, Clarke’s technique and attitude showed that the bass – in the right hands – could be as thrilling, engaging and popular as any other instrument.

Influential early solo works such as School Days and Journey To Love changed the way arrangements were perceived and the way music was listened to. As recently as 2011, his album The Stanley Clarke Band won the Grammy for Best Contemporary Jazz Album, and his new offering Up is a whirl of diverse energy as Clarke – switching between electric and acoustic bass (the latter was his first love, the former made him a star) and bringing in friends like Joe Walsh, Stewart Copeland and Corea – sounds buoyant and rejuvenated.

As for what genres it covers, from funk to cosmic meanderings, be ready and willing to lose count.

“I think it has an upbeat feel,” he says, “but it goes in many different directions. I called a lot of friends in to set the pace and tell stories and jokes and have fun, but fortunately my friends are good players! Stewart Copeland and I go way back, to even before The Police.

“The idea was to have a good time, not get too heavy about anything. But then, y’know, music has a way of getting serious on you! Especially with great players that have such elastic talents who use the whole emotional scale. Melancholy or high-powered, they can do all of it. It’s an album a listener can either glide or fly with.”

Clarke is well aware and perfectly content that his music remains tricky to box.

“I started out playing ballrooms, playing conservatively, because I thought a bass player had to do that. But I learned you could do so much more.

“Much as I love being called a jazz musician, it’s not actually what I really am. I studied the bass and I listened to a lot of excellent music by all kinds of guys. A guy playing saxophone in the street before breakfast would be an influence as much as anyone. And back in those days, I was into what was called acid rock, and Hendrix, as much as I was into classical musicians from another whole world. And my buddies were into Motown. So my musical tastes were with whoever I was in a room with at the time!

“I remember The Beatles on The Ed Sullivan Show and I didn’t like anything my sister liked so I pretended not to like it, even though instinctively I did! There wasn’t a lot of British music we’d hear then. But then the Stones came on and I thought: ‘That’s my group!’ Yet the bass player, Bill Wyman, always looked so sad. I thought: ‘What’s wrong with this guy?’

"It turned out that was just his personality, but I remember being fascinated that he seemed a little different: it made me think about being a bass player differently. I wrote music, but I’d stand at the back and the trumpet player was out front – and that guy couldn’t write shit! So I thought that was strange. As a joke, initially, I wrote songs on the bass and took a bunch of buddies into the clubs as The Stanley Clarke Band.”

It’s hard to believe The Stanley Clarke Band began as a joke…

“Kinda, yeah! It was just a nice, unusual experiment. And we never looked back.”

It was probably the mid-70s albums, especially 1976’s School Days, which made Clarke’s name in the UK. He co-produced it with British one-time Beatles engineer Ken Scott, who also worked on Supertramp’s Crime Of The Century and with Mahavishnu Orchestra and Billy Cobham (as well as on Bowie albums such as Hunky Dory and Ziggy Stardust).

“Ken was tremendous,” recalls Clarke. “When I finished the track School Days, Kenny said, ‘Now that’s a bass solo.’ Everybody in the studio said, ‘Um, but isn’t the bass mixed up a bit too loud?’ There was a moment. And Ken said, ‘When it’s played like that, it’s never too loud.’ So he was a big part of that breakthrough. It was a real milestone in both bass playing and ways of recording.” Clarke’s love affair with the four strings knows no bounds.

“See, I try not to go on about it too much, but I’m probably more of a true fan of the bass than most people. I get such a kick out of seeing bass players make albums, even now. That was completely unheard of back in the day. If some kid posts some bass-playing online, it might be the most godawful, terrible thing in the world, but I love it ’cos the guy’s doing something on bass!

“I’m all for creativity, for anything that falls under the category of bass liberation. I mean, I was so happy when Jaco Pastorius came on the scene. You have the right to be great, you have the right to be terrible, whatever. Bass will never again be, like, something that you think of last.”

Stanley detours to enthusiastically discuss other Up album tracks. Last Train To Sanity, which he considers one of the best pieces he’s ever written, shows “another side to me, the film-scoring side”. Gotham City is so called because his son is a big comic book fan. “I came to associate the track with some kind of parallel universe… it sounds from another world.” The liberally scattered “bass folk songs” form part of “a history of myself as a bass player”, while the 2013 live acoustic track La Canción De Sofia, a duet with old co-pilot Chick Corea “felt sacred”.

Perhaps oddly, Clarke also revisits School Days on the new album, presenting a new version of the much-loved song, with Jimmy Herring taking the lead guitar part.

“I knew people might think, ‘Why is he doing that again?’ Some people might say it’s blasphemy or suchlike. ‘How dare he?’ I apologise to anyone who feels I need to. But y’know what? I’m not a rock musician. Miles Davis re-recorded his classics; so did Coltrane. Like three or four times. And I have so many musicians asking me to play on it.

“If you notice my bass solo, I don’t try to outdo the original – I never could. Because what you hear on that isn’t just music. What you hear is a 20-something kid, who to all intents and purposes was wild, was trying to prove something to the world, was out there trying to change people’s impressions of the bass. That was me.

“And now as an older guy, I feel some of us really did create and document a new language, with melody, rhythm and harmony, for the bass. We’ve done a job. We’ve put it out there."

This feature originally appeared in Prog 51, in December 2014.

Chris Roberts has written about music, films, and art for innumerable outlets. His new book The Velvet Underground is out April 4. He has also published books on Lou Reed, Elton John, the Gothic arts, Talk Talk, Kate Moss, Scarlett Johansson, Abba, Tom Jones and others. Among his interviewees over the years have been David Bowie, Iggy Pop, Patti Smith, Debbie Harry, Bryan Ferry, Al Green, Tom Waits & Lou Reed. Born in North Wales, he lives in London.