“Dismissed as bland, complacent and of the establishment, it was now outsider music. If you wanted to be a true rebel, you came out as a prog fan”: Five essential neo-prog albums of the 80s

The second-wave movement didn’t last long – but its bands revitalised the genre with an attitude and energy that’s still being felt today

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

In 2015 Prog looked back to the short-lived neo-prog era, selecting five albums from the 80s that illustrate the power, energy and lasting influence of the British second-wave movement.

This wasn’t supposed to happen. According to the official, BBC‐approved version of rock history – you know, the one featuring footage of Rick Wakeman in a wizard’s outfit and the Emerson Lake & Palmer trucks rolling down the motorway – progressive rock was consigned to the dustbin five minutes after the Sex Pistols swore on live telly. Anyone who was remotely cool immediately binned every prog album they owned, cut their hair and got with the programme. Year Zero had arrived, and nothing that went before could ever dare to show its face again.

Nonsense, of course. But all the same, by the turn of the 1980s, there had unquestionably been a seismic shift in the UK musical landscape. All of which meant, ironically, that what had been dismissed a few years previously as the bland, complacent music of the establishment was now the ultimate outsider music. In the early 80s, if you wanted to be a true rebel, you came out of the closet as a prog fan.

In many ways, it shouldn’t be surprising that a new generation of prog bands should have come to prominence at that time. It fits in with the usual decade‐long cycle that sees those people who are fans at 13 or 14 soon pick up instruments and form bands of their own, and by the time they’re in their early 20s, they’re writing their own music informed by those teenage influences.

They soon found that there were plenty of people who wanted to hear it. Unfortunately, the neo‐prog scene’s time in the spotlight was a relatively brief one. And for that we can put the blame pretty squarely at the doors of Britain’s major labels.

Pallas, Twelfth Night and IQ all signed major deals after Marillion proved that prog could still prove a commercial force to be reckoned with – but attempts by the industry to build interest in the neo‐prog scene were half‐hearted at best. As the 80s turned into the 90s, the big deals were no longer on the table, and progressive rock’s great second wave had completely lost momentum.

But in many ways, that wave gave progressive music a lift with which to build itself back up. Later on, the rise of the internet helped bands forge more effective links with its audience and sell records and gig tickets directly to fans – a process pioneered by the neo‐prog bands. The revitalising spirit they injected into the genre is still being felt.

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

We present Prog’s selection of the top five essential neo-prog albums.

Marillion: Script For A Jester’s Tear (EMI, 1983)

Undoubtedly the record that put the Second Wave of British Prog on the map. Long-form songwriting and ear-catching musicianship (Steve Rothery’s guitar lines and Mark Kelly’s keyboard hooks have rarely been more sublime) were shot through with a charisma and lyrical bite not seen since the prime of a certain band beginning with ‘G’ to whom Marillion were incessantly compared.

The melancholic melodramatics shot through these six compositions were repeatedly offset by Fish’s intense, angst-ridden vocals, touching on heartbreak, heroin addiction, urban isolation and the troubles in Northern Ireland en route.

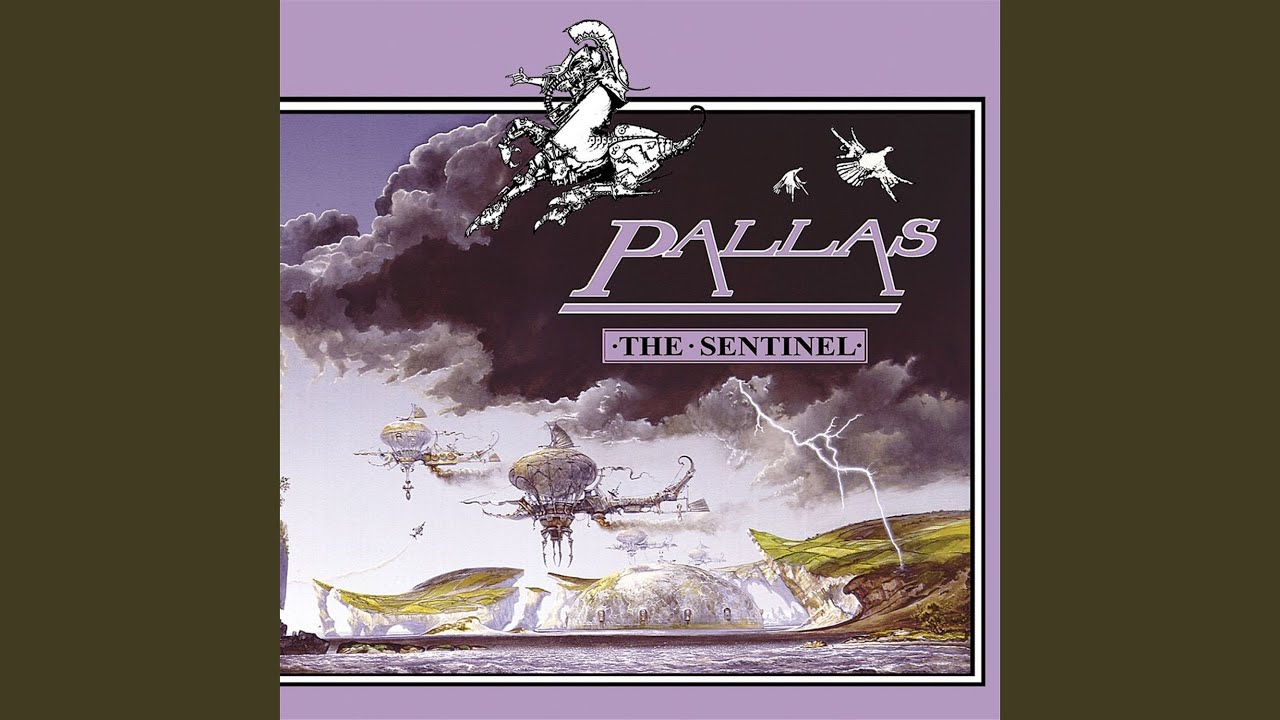

Pallas: The Sentinel (Harvest, 1984)

The Aberdeen outfit’s initial intention to make a concept album out of their Atlantis Suite song cycle was scuppered by their label switching the running order and including more commercial tunes. Yet this is still a fine record, even if the central conceptual narrative is somewhat disjointed by the rearranged tracklisting.

The driving synth-rock of Arrive Alive (Eyes In The Night) grabs your lapels with its instant hook and jumpy tempo, then Cut And Run and Shock Treatment reinforce the dystopian sci-fi theme with some gusto. But more lasting pleasures can be found in the sweeping symphonic pomp of final track Atlantis.

Pendragon: The Jewel (Elusive, 1985)

Neo-prog had gone fully overground by the time Pendragon released their first full-length album. The upbeat prog-pop of Higher Circles that opens the set reflects the distinctly radio-friendly style it was now adopting, but the plot thickens considerably on the trippy, windswept Alaska and the staccato rhythms of Circus.

Yet throughout, the stirring, heart-on-sleeve romanticism that has characterised their best work since this album is already high in the mix, courtesy of Nick Barrett’s distinctly English, folk-influenced vocals, the Moog-heavy melody patterns and piercing guitar excursions.

IQ: The Wake (GEP, 1985)

The Southampton neo-prog survivors’ second album is widely regarded as their defining early statement, and the 1985 long-player manages to marry a distinctive, soaring synth sound with a punky, agitated tempo and some seriously dizzying time signatures.

Peter Nicholls’ fragile, uneasy vocal has a drowning-not-waving quality to it that’s strangely magnetic, even if his years listening to Peter Gabriel have obviously rubbed off heavily. What really stands out, all these years later, is the sheer strength of the melodies – something that has helped IQ endure as a band to this day.

Twelfth Night: Fact & Fiction (Twelfth Night, 1982)

From the eerie, childlike singing that fills the opening bars of We Are Sane, it’s clear that this first studio album release from the neo-prog pack was taking a distinctly different tack to the Tolkien-esque textures associated with the original prog movement. The use of samples on that track and This City add spooky atmospherics to the sonic stew, and there are strong hints of Peter Hammill in Geoff Mann’s malevolent, theatrical vocals.

Mann would leave the band soon afterwards, and the group would pursue a broader, more accessible style on subsequent albums. But as a startling statement of how the new breed could shake up a supposedly moribund genre, this takes some beating.

Johnny is a regular contributor to Prog and Classic Rock magazines, both online and in print. Johnny is a highly experienced and versatile music writer whose tastes range from prog and hard rock to R’n’B, funk, folk and blues. He has written about music professionally for 30 years, surviving the Britpop wars at the NME in the 90s (under the hard-to-shake teenage nickname Johnny Cigarettes) before branching out to newspapers such as The Guardian and The Independent and magazines such as Uncut, Record Collector and, of course, Prog and Classic Rock.