The story of Pallas' major label debut The Sentinel

The Sentinel was supposed to make Pallas stars. Instead it's a tale of ill fortune and a fabled producer whose eye came off the ball

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

Pallas’ debut album should have been the launch pad for a career to rival the success subsequently enjoyed by Marillion. But behind The Sentinel lies a convoluted tale of high expectations dashed by ill fortune and a fabled producer whose eye came off the ball.

While The Sentinel was Pallas’ first studio effort, their first release was Arrive Alive, a 1981 live album. Arrive Alive and some energetic live shows, most notably at London’s iconic Marquee Club, brought the band to EMI’s attention. “We were going to London a lot, gaining a solid following and good press reviews,” recalls bassist Graeme Murray of the band’s exhilarating early southern forays.

Having been signed by EMI, Pallas started work on what would become The Sentinel, renting a farmhouse in north east Scotland. “We just shut ourselves in there,” Murray continues. “We wrote a couple of atmospheric, late night compositions and I remember that we had the opening sequence of Rise And Fall with its rising chords.” With the band conjuring up the visual image of “something huge rising up out the ocean”, the seeds were sown for the album’s concept. “We had this idea of the Atlantis legend and came up with a storyline.”

“Atlantis was the track which gave rise to the whole album,” adds singer Euan Lowson. “I had been away for a couple of months in the summer on a Euro railcard. When I got back the other guys had completed about three minutes of the big intro. It was particularly inspirational and I saw down and wrote a lot of the storyline around it.”

Murray describes Pallas as “a band that has always written musical pictures” and The Sentinel painted a very visual picture adding a modern gloss to the Atlantis story. “We found that visual images helped us in the creative process to come up with musical ideas. We started forming the lyrics around the storyline.” The band proceeded to spend considerable time jamming to create some of the tracks on the album and embellishing musical themes which they would weave across different tracks. “It’s something that we have done since,” Murray adds. “I think it gives coherence to an album if you have some recognisable melodies cropping up in different tracks.”

Arrive Alive was an obvious candidate for inclusion on The Sentinel as the band felt that it had radio appeal (and it did flirt briefly with the singles chart). But all the material on the album otherwise was created for it in a dedicated manner and honed through live performances.

Beavering away in their rented farmhouse Pallas wrote far more material than necessary or physically possible for a single album. And that was one issue that would hamper The Sentinel. “Back then you were constrained by the fact that you were putting your album out on vinyl,” Murray points out. “So realistically you required 40 minutes but we could have easily had a double album.”

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Discussions were held with EMI on the topic – they baulked at the idea. “They just about had a heart attack at the prospect of signing and launching a new band with a double concept album in the midst of the new wave!” laughs Murray.

With the wonderful wisdom of hindsight Murray recognises that Pallas’ gameplan was imperfectly conceived. “In retrospect our first EMI album shouldn’t have been The Sentinel. We should probably have re-done the stuff that was on the Arrive Alive album. And then we could have done a double album next.”

EMI may have demurred at the idea of marking Pallas’ debut on the label with a double studio album but having asked the band which producers they’d like to work with, they pushed the boat out by securing Yes producer Eddy Offord. Other names mooted were Steve Lillywhite and, bizarrely, Chic’s Nile Rodgers. Working with Offord held enormous appeal. Not only was Offord available, but he also liked the demos that he’d heard. “We were huge Yes fans,” says Murray. “The prospect of going out to record the first album in America with him was like a dream. We were swayed not only by a trip to Georgia but also the chance to work with someone who was a hero to us, a legend.”

Immediately prior to departing the UK for their American adventure, Pallas played the Reading Festival, airing much of the material that would feature on the album. Murray remembers: “We were on stage at teatime on Friday and then flew to Atlanta the next day so it was a very exciting time in our lives.”

Being in the studio with Offord was everything Pallas had hoped for, professionally and socially, as they spent the next two months sequestered in his Atlanta studios. “There were so many stories about Eddy and they turned out to be true – he was a real character to work with,” Murray chortles. “It was a busy time and we learned a lot obviously. He certainly made us work harder on the vocal front with the big harmonies, which I suppose came down to the work he had done with Yes.”

Away from home, the band worked hard and played hard. “We would work until past midnight and then Eddy had his favourite pub which was a Florida crab shack – he would take us there every night. I think Eddy was pleased to be working with a British band again because he had gone out to live in America and was working with lots of southern rock bands. He enjoyed the fact that we were so fired up and enthusiastic too.”

That said, Murray has sometimes questioned whether the band would have done better to work with a more contemporary producer, recalling Offord’s reaction when they listened to Yes’s 90125 together. “I was blown away by it, but I think Eddy found some of the things that were happening on there a bit radical.”

Offord’s working methods were very organic with his studio set up in an old cinema. “His studio was unconventional. We set up on the stage in the cinema and his desk was down in the stalls. There was no control room and live room. Basically it was like setting up for a live gig and he was down in the front stalls doing the mixer and monitors. Effectively the control room was set up in the front stalls but there was no physical barrier between Eddy and his desk and the band!”

“Eddy was sometimes doing three things at once, while watching his beloved baseball team on a monitor on top of the second desk,” adds Lowson.

Offord had some useful contacts which he milked for Pallas’s benefit. Steve Morse (then of the Dixie Dregs, subsequently of Kansas, Deep Purple and Flying Colors) lent the band guitars while another contact provided a synclavier. “That gave us what were then some very new keyboard sounds,” says Murray. “We were trying to make it more modern; we didn’t just want to sound like we were replicating something from 1972. We were trying to update things within a reasonably limited budget. We had taken all of our own stuff over with us as luggage!”

While Offord’s studio and recording techniques may have been unusual, recording of the album went smoothly. However The Sentinel swiftly ran into problems thereafter. Having run out of time in Atlanta and with their visas expiring, Pallas returned home to the UK with some rough mixes, leaving Offord alone to mix the album properly. It was just as Offord was invited to record The Police live on tour.

Back in the UK, the final mixes arrived, and Pallas were shocked by the flimsy-sounding results. “We were gutted,” says Murray. “We were absolutely 100 per cent convinced that someone else came in and mixed it for Eddy because it just did not sound like it had when we were in the studio working with him. Anybody who

has seen us live knows that the band is really powerful and we felt that it just didn’t convey that power we’d heard in the rough mixes as we’d been going along.”

This wasn’t the only mystery in Pallas’ time at EMI. “When we signed to them there was a team put together to make the Harvest label great again,” Murray reveals. “They’d had Deep Purple and Pink Floyd had been on there at some point. Now they wanted it to make Harvest a signature rock label again.” Pallas were involved in this project in its infancy. But on their return from the US they discovered that the entire team had been sacked. “We came back to head office with our new album and they were going, ‘Who are you again?’”

Thirty years later what happened to The Sentinel mixes still perplexes the group. “It was a disappointment. We were never happy with the way it sounded because we knew that in the studio it was more exciting and had far more of an edge.” Allied to the weak mixes was the double-album concept reduced to a single disc with a jumbled running order and a slug of key material excluded.

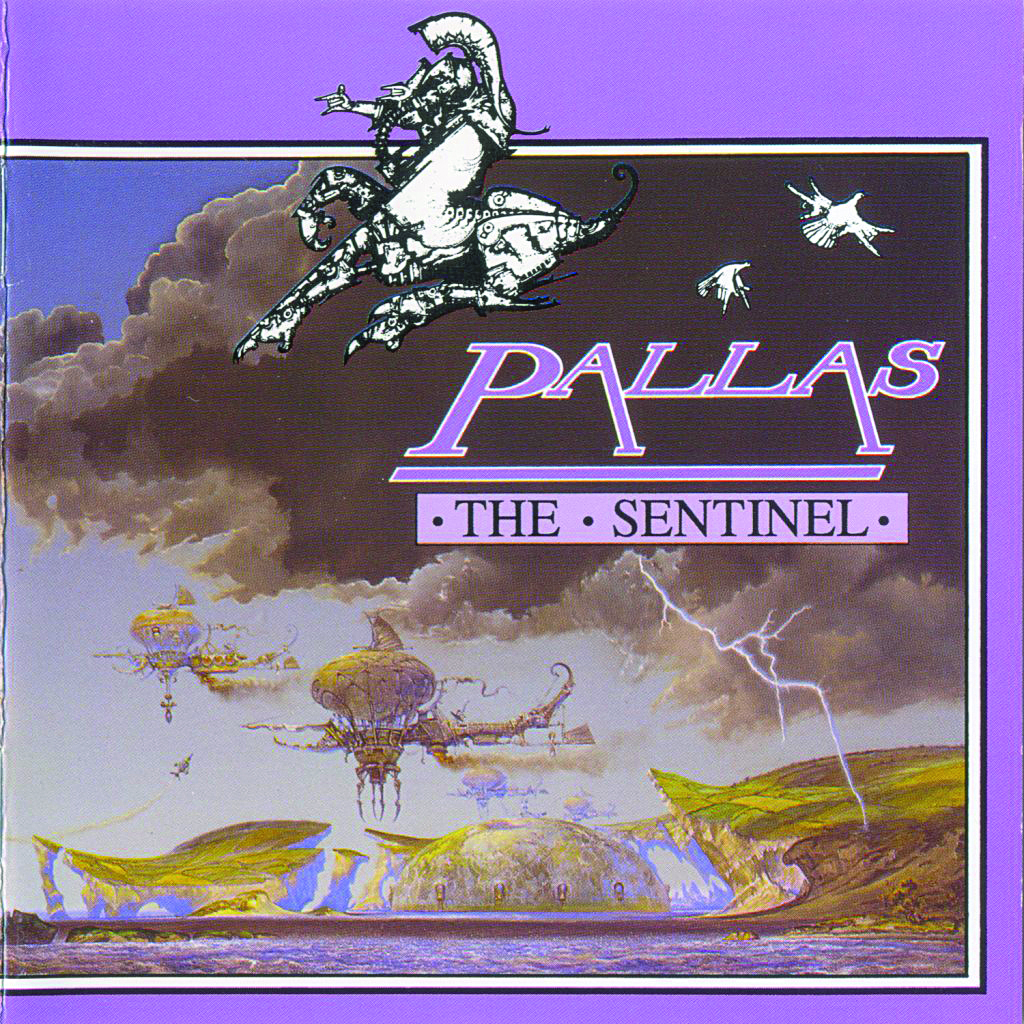

The Sentinel was remixed for its US release and the album benefited from the addition of Patrick Woodroffe’s timeless artwork. And while EMI’s PR machine got behind the album and the band would tour it, ultimately Pallas were promoting something that was a pale shadow of what they had planned. “It was difficult for us to enthuse about it knowing that we had all heard something so much better,” says Murray.

Pallas would eventually release The Sentinel as they’d intended with The Atlantis Suite intact – tracks Eyes In The Night, Cut And Run and Shock Treatment were parts of this, redistributed across the first disc – on a 1992 reissue for the Centaur label. But the original album was hardly a disaster, reaching Number 41 in 1984 – not bad for a band who had not had Marillion’s run of luck with radio play, press and charting singles.

What would throw a further spanner in the works was the departure of singer Lowson prior to the recording of second album The Wedge. In a smart move, the band drafted in Abel Ganz singer Alan Reed, who would front the band until 2010. However drifting into a semi-dormant state after The Wedge nearly halted the band’s aspirations, and only with new singer Paul Mackie and 2011’s XXV album have Pallas started to amass serious momentum once again.

This article originally appeared in issue 38 of Prog Magazine.

Nick Shilton has written extensively for Prog since its launch in 2009 and prior to that freelanced for various music magazines including Classic Rock. Since 2019 he has also run Kingmaker Publishing, which to date has published two acclaimed biographies of Genesis as well as Marillion keyboardist Mark Kelly’s autobiography, and Kingmaker Management (looking after the careers of various bands including Big Big Train). Nick started his career as a finance lawyer in London and Paris before founding a leading international recruitment business and has previously also run a record label.