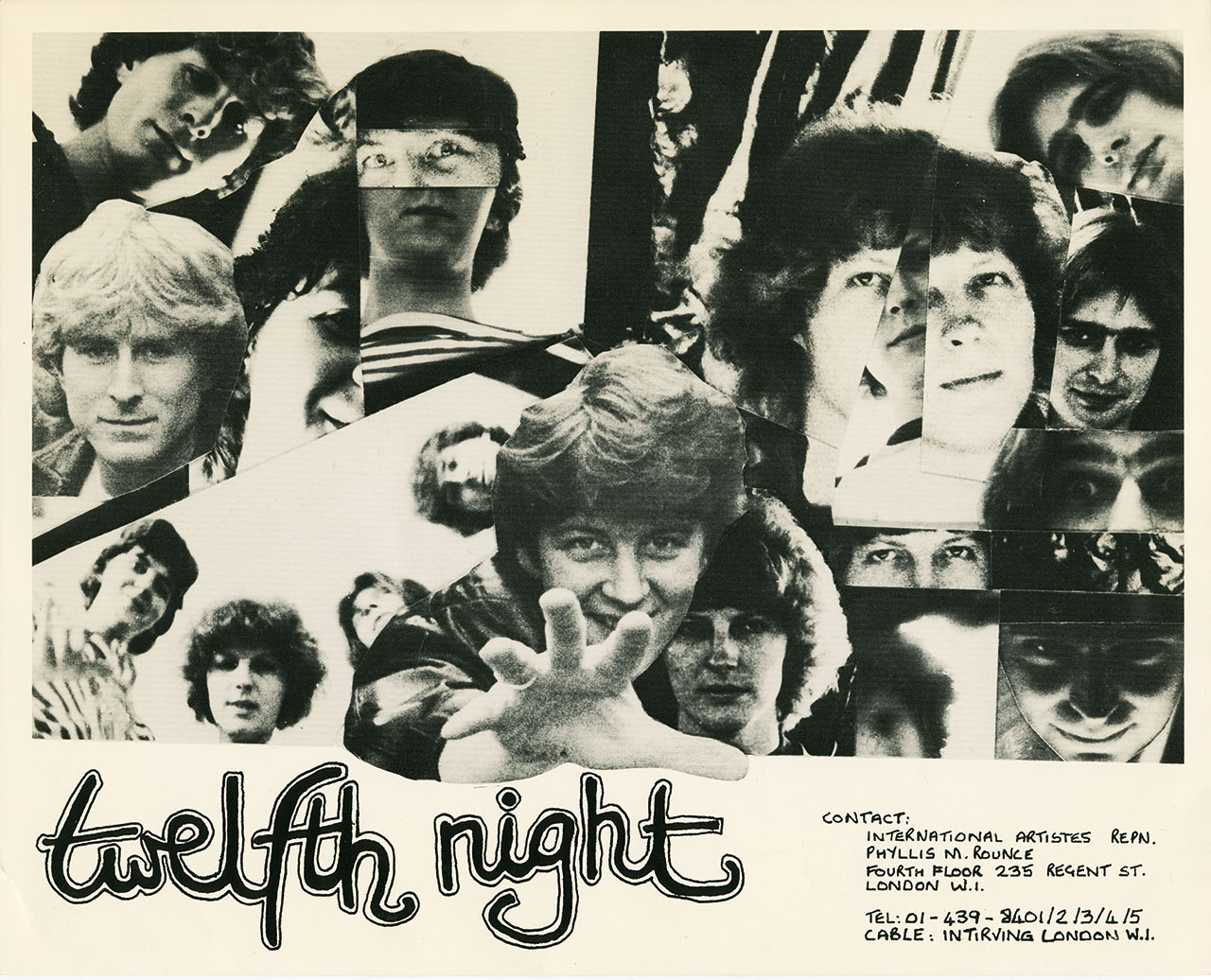

“There was this theory that once one major label had got a prog band, all the others would follow suit, but it didn’t really work like that.” The story of Twelfth Night's Fact And Fiction

Reading prog rockers Twelfth Night were the first of the 80s proggers to release their debut studio album

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

In many ways the history of Twelfth Night is a history of bad luck and what-ifs. A bad call here, some bad luck there, a band blessed with an abundance of ideas and spectacular musicianship who always seemed to be in the wrong place at the right time and vice versa. And yet, through it all, they left a significant body of work that helped fuel the re-emergence of progressive rock in the 1980s and cultivate a new generation of fans. At its heart is Fact And Fiction, their only full-length studio vinyl release with late and much-missed vocalist Geoff Mann.

Think 80s prog revival and the first name on most people’s lips would be Marillion. And yet, for a while, it seemed possible that Twelfth Night would be the first of the new bands to break through. They already had the instrumental vinyl album Live At The Target (February 1981) and three cassette albums (which included 1982’s celebrated Smiling At Grief) under their belts. They even opened the 1981 Reading Festival. It was all looking incredibly promising.

Released in December 1982, three months before Marillion’s Script For A Jester’s Tear, Fact And Fiction could, and quite probably should, have been the album that catapulted Twelfth Night to greatness. That it didn’t owes much, perhaps, to the long period of time it took to record. This was primarily down to the recording deal (of sorts) they had struck with Andy MacPherson, the owner of Revolution Studios in Cheadle Hulme, near Manchester. As drummer Brian Devoil explains: “It was recorded, for free, in down-time in a professional studio thanks to the generosity of the owner.” As it turned out, however, MacPherson was only really interested in the band’s cover of Eleanor Rigby. “He thought he was going to get a hit,” says Devoil.

Article continues below

The history of the recording of Fact And Fiction is meticulously chronicled in Andrew Wild’s biography Play On. Suffice to say that circumstances were somewhat unusual. Not only did the band lose time to a studio rebuild, which put the start date back from March to May, but, given the nature of the studio time on offer, they had to take what they could get, when they could get it. With the whole band except Geoff living in Reading, they would often stay at his Salford home, rehearsing in his cellar by day, and pitching up at the studios to record by night, with engineers who sometimes seemed less than devoted to the cause. For guitarist Andy Revell, who was also working as a research scientist at Reading University at the time, the arrangements were a logistical nightmare. As he told Andrew Wild: “I remember once running experiments from about 9am until about 4pm, driving to Heathrow and flying up to Manchester, recording all night and then flying back south for more experiments the next morning. I was shattered and deeply frustrated.”

These arrangements also meant a period of inactivity as a live band. As Devoil explains: “We couldn’t plan to do any gigs because we didn’t know when we were going to be recording.” Not that this stopped the band from appearing on BBC1’s The David Essex Showcase – a kind of television talent show – in June ’82, miming to a re-recorded version of East Of Eden. Despite the exposure, it can’t be said that the band was shown off to best effect.

Their ability to perform live was also affected by the loss of keyboard player Rick Battersby during November ’81’s Smiling At Grief sessions. While keyboard duties for Fact And Fiction were handled admirably by bassist Clive Mitten (“I’d never owned a keyboard, let alone played one”) playing live was a different matter. The band did return to the road as a four-piece in September ’82, but this proved difficult, and by November, after the completion of Fact And Fiction but before its release, Rick had made a welcome return.

Taking time over the recordings meant that the songs were better rehearsed and more fully developed, but there is a view that the time off the road proved crucial. “We were out of the public eye, without gigs, for quite a long time,” says Brian Devoil, “and that certainly gave Marillion the chance to catch us up and overtake us.” Not that, initially, he saw that as being too much of a problem. “I always felt there was room in the market for four or five big bands,” he explains. “There was this theory that once one major label had got a prog band, all the others would follow suit, as they had done with the punk bands in an unseemly scramble, but it didn’t really work like that for the prog bands.”

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Nevertheless, the announcement of Marillion’s deal with EMI, in September 1982, did influence Fact And Fiction, as the band rethought both the running order and track selection. Notably, some of the shorter, more commercial songs were dropped, and Human Being was reworked and extended, even incorporating a bass solo. The decision was also taken to leave Eleanor Rigby off the album, which meant that although it was finally released as a single on REVO records in October – the same month as Marillion’s Market Square Heroes – little effort was made to promote it. Feeling they had little left in common with Revolution, the band took a loan to buy the recorded tapes, quickly remixing them and eventually putting Fact And Fiction out on their own label, Twelfth Night Records.

We’ll never know what would have happened had Fact And Fiction been recorded with major record company backing and a well-chosen, committed producer, but what we do know is that Fact And Fiction is chock-full of exciting, stimulating and emotive material that made a huge impression on new and existing fans alike.

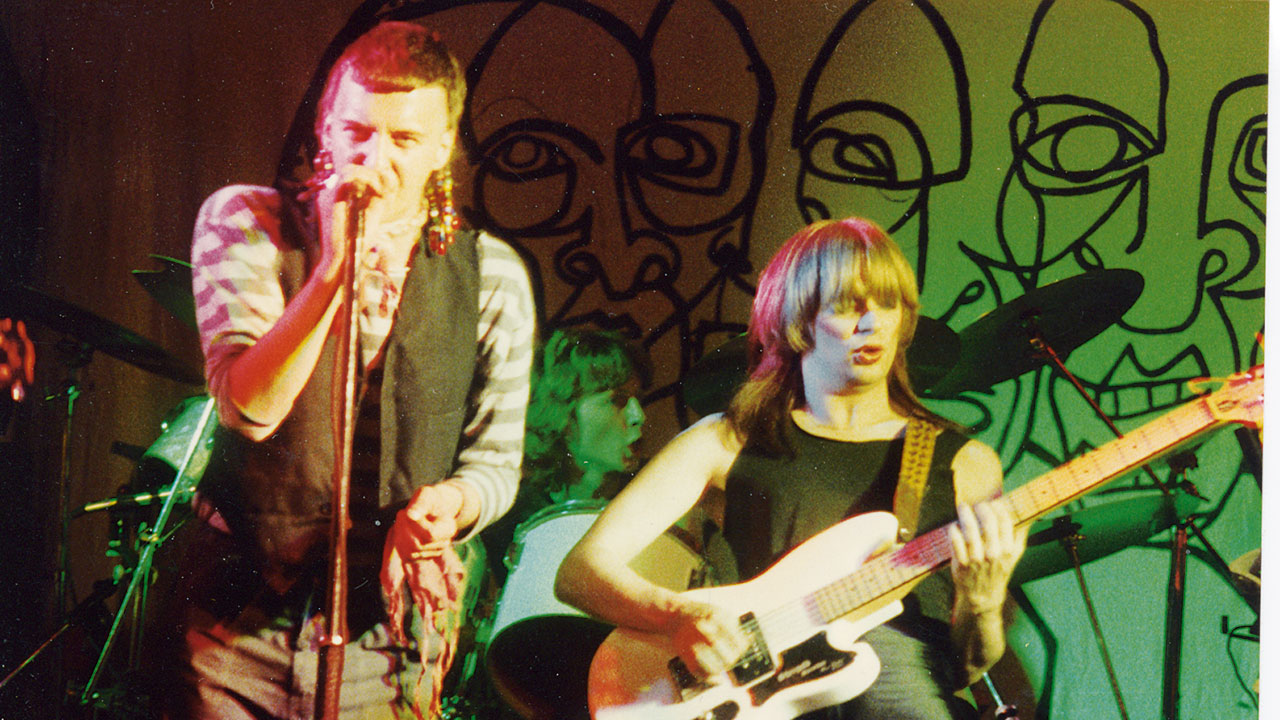

So what of the music? Well, while few would quibble with the ‘progressive rock’ tag, there’s an aggression and sense of purpose on Fact And Fiction that sets Twelfth Night apart from most of their predecessors. At times, too, there’s a discernible new wave or indie edge, a glorious harshness of sound that’s not at all typical of the genre, and which sets Twelfth Night apart from their peers. Listen, for example, to the third part of the epic album opener We Are Sane, or the keyboard (Clive’s Korg PolySix synth) dominated title track, or the more unsettling parts of Creepshow. “Punk Floyd” was the term coined by Andy Revell to describe the music at the time – that said, there are plenty of more familiar prog traits on display in their songs: gentle and subtle musical passages, layered synths, soaring solos, inventive drum patterns and wonderful bass lines. And in-keeping with prog tradition, Fact And Fiction is also home to the instrumentals World Without End and The Poet Sniffs A Flower.

Though the whole band would contribute to the later-stage development and arrangement of the songs, the original album sleeve credits Clive Mitten and Geoff Mann with the “initial composition” of music and lyrics respectively. Mitten is quick to point out the extent to which he and Geoff worked together, with Mitten’s music displaying strong influences from progressive and heavy rock, and Mann bringing a U2 and Joy Division influence to the table. “We Are Sane was written in one afternoon,” says Mitten. “The music was designed absolutely to fit the words, which is why the track is such a one-off oddity, really, and my favourite.”

According to Mann’s widow, Jane (who, incidentally, contributes backing vocals on the album), “Geoff was very proud of the album, particularly his contribution to the lyrics and the artwork. He was very fond of This City as he felt it encapsulated the Salford we lived in.”

Throughout, in fact, Geoff’s lyrics are rousing and incisive as he turns his wit and way with words against rampant consumerism, social conformity, suppression of the individual, the nuclear arms race, and ‘selfish desires’ that ‘simply lead to pain’. And then there’s Love Song, an anthem to top all anthems, and as strong an illustration as you will find of the vision and belief that lay behind all of Mann’s work.

Mann also contributed all the album artwork – the interlocking heads on the cover, the handwritten lyrics, the gatefold illustrations – drawing words and images together to give the album a strong coherence. It’s powerful stuff.

Initial reviews were mixed, with Prog’s own Malcolm Dome, then writing for Kerrang!, critical of the production and the vocals, but describing Fact And Fiction as ‘an unfulfilled masterpiece’.

In his book, Andrew Wild calls it the band’s “breakthrough album”, but Devoil is not too sure: “I don’t really feel it was particularly. Fact And Fiction helped us get into the Marquee and become a headline band there and do Reading in ’83, but it wasn’t like there was a sea change, like with Live And Let Live, for example, which came out on a proper label and had more effective distribution. Musically it was a very significant album, but it wasn’t a breakthrough in terms of commercial success.”

And perhaps it is as a musical statement that Fact And Fiction has, over time, revealed its true hand, with the staples it served up for Twelfth Night’s live set becoming some of the band’s most revered, anticipated tracks. It is a triumph of talent over circumstance and can quite rightly be regarded as one of the pillars of the progressive rock revival.

According to Clive Mitten, “It is cited frequently as an album that stands apart from much other ‘prog’ from that period. It’s a complete mish-mash of styles and there was no limitation really on what you should be thinking or trying.” (A claim borne out by some of the intriguing bonus tracks on the 2002 reissue.) He says he is “pleased but a little surprised” to see the album featured in an Albums That Saved Prog series.

Jane Mann says that Geoff “would probably be astonished, particularly this far down the line”.

Is Devoil surprised by this accolade? “Yes, because we don’t think in those terms, and it’s a very big, grandiose title. But then again, if it means the albums that brought prog back a bit in the 80s, post-punk [Which indeed it does – Ed], then I suppose I’m not surprised, because it was one of the first and it’s stood the test of time. We’re still selling the album now and I think the quality of the ideas and songs is still very good.”

Perhaps Devoil has found the key to the band’s lingering frustrations. “Musicians are always able to ponder what might have been,” he says, “whereas listeners tend to accept an album for what it is.”

This feature originally appeared in issue 37 of Prog Magazine.