“Lyrically, it’s something that makes Samuel Beckett sound like Tommy Cooper." Tim Bowness and the story of Flowers At The Scene

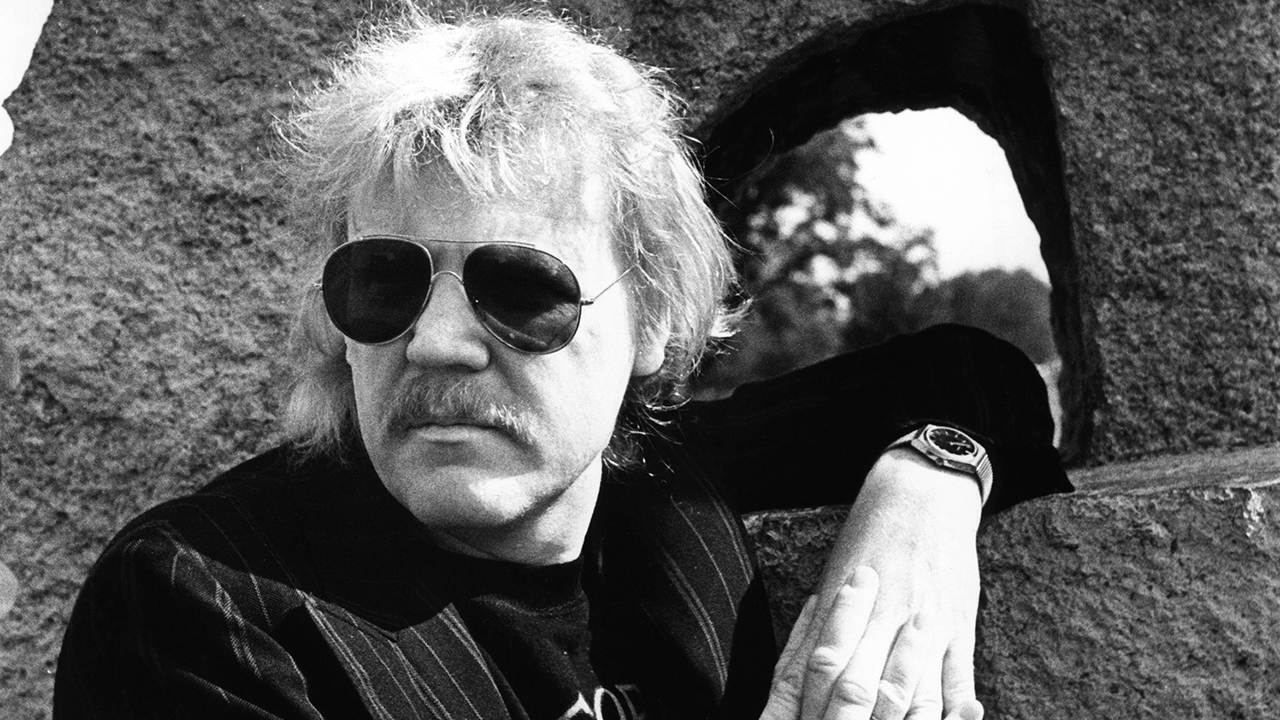

Tim Bowness may explore morose subjects like murder and divorce on his new album, but this collection of “cinematic short stories”, featuring an impressive prog line-up, is certainly not all doom and gloom…

He may adopt the facade of extreme drollness but when Prog spoke to Tim Bowness about his fifth solo abum Flowers At The Scene in 2019, he pointed out that there’s something distinctly uplifting about his music.

“I’m alive! Which is something, I suppose.”

So begins our conversation with Tim Bowness, as he responds to the traditional greeting, “How are you?”

If that makes the Bath-based songwriter sound like a downbeat, morose character, you’ve read him wrong. And the same can be said for his sometimes desolate-sounding music. For all the apparently gloomy subject matter found on his new album Flowers At The Scene, he rightly points out that there’s something distinctly uplifting about his music. It runs through his beautifully evocative, if often melancholic, solo material, right back to the early 90s No-Man records that put him and erstwhile musical partner Steven Wilson on the map.

“Lyrically, it’s something that makes Samuel Beckett sound like Tommy Cooper,” he says of the new album. “But as with No-Man, we had bleak lyrical preoccupations but there was something quite positive in the music accompanying them. I think that’s the case with Flowers At The Scene.”

Admittedly, the album’s lyrics sketch scenarios ranging from death to divorce to post-apocalyptic survival, but there’s a warming quality to Bowness’ whispering vocal style, and a romantic yearning on tracks such as Rainmark and Ghostlike that is totally captivating. Meanwhile, on The Train That Pulled Away, despite signing off with the line, ‘If it didn’t kill you then, you knew it’d kill you later,’ the steam train rhythm and elegant strings conjure up images of a majestic old Pullman gliding through a wintry landscape. What’s not to like?

An open, engaging and often drily amusing character, you also sense that Bowness is acutely conscious of his own good fortune to be doing the job he loves. Hence the greeting at the beginning of this piece.

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

In contrast to the concept-driven piece that was 2017’s Lost In The Ghost Light, he describes Flowers… as “11 cinematic short stories” and plays down the notion that the scenarios presented are autobiographical beyond “fragments that are very personal”. Of the title track, which concerns the reaction of a family to the death of their son, he insists, “It wasn’t something I was expecting to write or wanted to write.”

Inspired by a two-line downpage news snippet about an all-too-familiar urban murder, it explores the repercussions beyond the terse reporting.

A moving collage of snapshots creates a mundane but keenly felt domestic drama: ‘breakdowns in the shower’; ‘muffled tears in the hall’; ‘postcards from the team’, along witha sense of typically British difficulty in dealing with heavy emotions: ‘can’t admit to what you’re thinking’.

“It tells a story of a family trying to come to terms with the death of one of their children, who’s been stabbed at a bandstand in a park,” says Bowness. “As a parent you find these stories terrifying. And it’s strikingly pointless – if you think about knife crime in London, or Manchester, where I’m from, they’re just casual gang killings but these people are somebody’s child, husband, boyfriend… it’s looking further into something that’s a two-line article in The Independent.”

That explanation hints at Bowness’ own domestic situation – “common-law married, as they used to say” and father to an eight-year-old boy, Sonny. But he says we’d be wrong to read too much literal relevance into an even more strikingly poignant song on the album, Not Married Anymore.

‘There’s nothing you don’t miss, not the toys, the chaos or the shopping lists,’ he muses despondently. Ouch.

“It’s an exaggeration of reality,” he says. “An extreme version of certain frustrations that anybody would feel. There’s a time in any relationship especially when you’re bringing up young children when it’s incredibly intense and chaotic and there are many times when you feel like giving up on situations. Relationships are hard work.”

The atmospheric, synth-soaked scene of Ghostlike also speaks of relationship strife, as the protagonist watches a woman ‘swimming in a hotel pool’.

“It’s the last vestiges of a relationship, with someone looking on what is about to be perhaps their ex-wife.” The hints that this woman is now consigned to his past is striking and suggests all manner of slightly alarming possibilities.

And yet, for a man whose own life has featured considerably more turmoil and tragedy than most, the 55-year-old takes a dim view of some artists’ tendency towards self-pity.

“We had a lot of tragedy when I was growing up. I was an only child with unhappy parents who continually split up, and when I was about 15, my mum was killed in a car crash, one of my grandparents died within six months of that, and another had nervous breakdowns. So I had bizarre things like coming home from school and seeing men in white coats carrying my grandmother on a stretcher, screaming into an ambulance.”

He describes music, and to a lesser extent books and films, as “a total escape” from that, but he still feels little sympathy for those artists he sees taking out their own troubles on others.

The War On Me is the one track on this album that seems to pick up where Lost In The Ghost Light left off. Where that album concerned an ageing musician mulling over his life, this sees a similar character convinced that the world is out to get him.

“There’s a humorous element to it, because he is ludicrously self-pitying,” Bowness explains.

It’s The World has a similar theme, a lyric he describes as “someone blaming everything external on what was probably an internal problem – self-pity on a global scale.”

For Bowness, it’s important to step back sometimes from what can be a very insular profession.

“When you’re involved in music it’s a complete obsession. It means everything to you. But I’ve always had a realisation that it means utterly nothing to most people I meet – even to most of my family, so you’ve got to get a perspective on what you do.”

He’s not the only one in his immediate circle of collaborators who feels this way.

“It’s one of the things I have in common with Steven Wilson,” he says. “We share a profound passion for what we do but also a realistic perspective of how important it is in the wider world. When we were signed to One Little Indian in the 90s we certainly met a lot of people who probably thought they were the descendants of Christ! [Laughs]

“And sometimes it was a licence to treat others very badly. Have you seen the film Round Midnight? It’s a depiction of a struggling jazz musician in Paris who’s pretty horrible to the people around him. Regardless of the talent of that individual, it’s not an excuse to treat everybody around you like dirt.”

It’s The World features a guest vocal from a man who epitomises, for Bowness, almost the opposite of the clichéd charming entertainer who is a monster in real life – Peter Hammill.

“I’ve known him for a few years, and he does embody that contrast: his music’s intense, it’s forbidding, it’s frightening. And yet he is perhaps the friendliest, most generous person you’re ever likely to meet.

“The only problem with that is I’m now scared for myself because when I think about people like Chet Baker, John Martyn, Stan Getz, like me they’ve got a more gentle style of music, and yet as people they’re monsters. Ha! So I could be on the opposite end of the scale from Peter Hamill and not know it…”Based on our encounter, I think we can safely reassure him otherwise.

For a man who seems unsure about how amenable he is, Bowness has no shortage of friends among his fellow musicians. His 30-year professional relationship with Steven Wilson is reflected in the latter’s mixing skills and occasional instrumental contributions, while, in addition to Peter Hammill, long-time Bowness heroes Kevin Godley and Andy Partridge also appear. Meanwhile, the licks of Fates Warning guitarist Jim Matheos light up several songs, as does the jazz drumming of Dylan Howe, Ian Dixon’s atmospheric trumpet, and flute and backing vocals from Big Big Train’s David Longdon. Meanwhile, Alistair Murphy, aka The Curator, wrote a breathtaking, Philip Glass-style string score to The Train That Pulled Away.

The key contributor to this record, however, is arguably the least high-profile. A man described as “fellow Northern miserablist” Brian Hulse was Bowness’ creative foil in his first band, Plenty, an art-pop project they reincarnated last year, re-recording their original 80s output.

“We continued to write together for this record, and he was my creative sounding board,” says Bowness. And if that reflects Bowness’ urge to revisit previous projects, we are also awaiting the long-promised new album from Tim and Peter Chilvers, a sequel to 2002’s stunning California, Norfolk. “It’s complete but I’m not sure when it will be released,” he admits. “Peter works as Brian Eno’s main assistant, and other work has got in the way.”

Another rekindled project that has also jumped the queue in the meantime is No-Man, whose first album in 11 years has already been written and recorded.

“Over the past couple of years there’s been a real sense of coming home. The Plenty album we called It Could Be Home, because it really felt almost like a place you lived 20 or 30 years ago, forgot about and then thought, ‘God! This is really nice!’ When I’m writing with No-Man there’s a similar sense; a return to some place special that you’ve not been to for quite a long time. Although I think what we’ve come up with is going to surprise a few people because it is very different to the other albums.

“I got together with Steven and it was one of the most exciting and enjoyable recording sessions we’d had since the 90s. We had a kind of three-day all-day, all-night session of just seeing what could happen with the music and that was tremendous fun, as well as being quite emotional.

“We’ve written the album basically and between now and April I’ll re-record most of the vocals, and we’re getting some other players to overdub on the album. Then in April, when Steven comes back from tour, he’ll be doing the final mixing. So we’re hopefully looking at an August/September release. I’m excited about that, and we’ve also talked about doing a No-Man tour, so we’ll have to see about that.”

All told then, not a bad time to be alive…

Johnny is a regular contributor to Prog and Classic Rock magazines, both online and in print. Johnny is a highly experienced and versatile music writer whose tastes range from prog and hard rock to R’n’B, funk, folk and blues. He has written about music professionally for 30 years, surviving the Britpop wars at the NME in the 90s (under the hard-to-shake teenage nickname Johnny Cigarettes) before branching out to newspapers such as The Guardian and The Independent and magazines such as Uncut, Record Collector and, of course, Prog and Classic Rock.