Big Big Train: "We're proud to be defined as a prog rock band"

Quintessential Englishness, astrology and crows: less than a year since their last album, Big Big Train are already back with album number 10, Grimspound

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

In the grounds of Nottingham Castle stands the statue of an airman with an angel at his shoulder. Erected in 1921, the statue has resisted the decades of wind and rain, even if the bronze detail of biplanes on its plinth is beginning to lose its battle with the elements.

The man the statue is based on is Captain Albert Ball VC, a World War I fighter pilot from Nottingham. At a time when military men were heroes, Ball was the equivalent of a rock star. He was a hyper-efficient killing machine – during his brief 14-month career, he shot down 44 enemy planes. But he was a man of letters too, a quiet, reserved thinker who questioned the morality of war.

Like so many of his compatriots, Ball’s career was fatally cut short over the fields of northern France. He may have been shot down by an enemy plane or he may have lost control of his aircraft, no one can say for sure. He reportedly died in the arms of a young Frenchwoman, named only as Mme Lieppe‑Coulon. He was just 20.

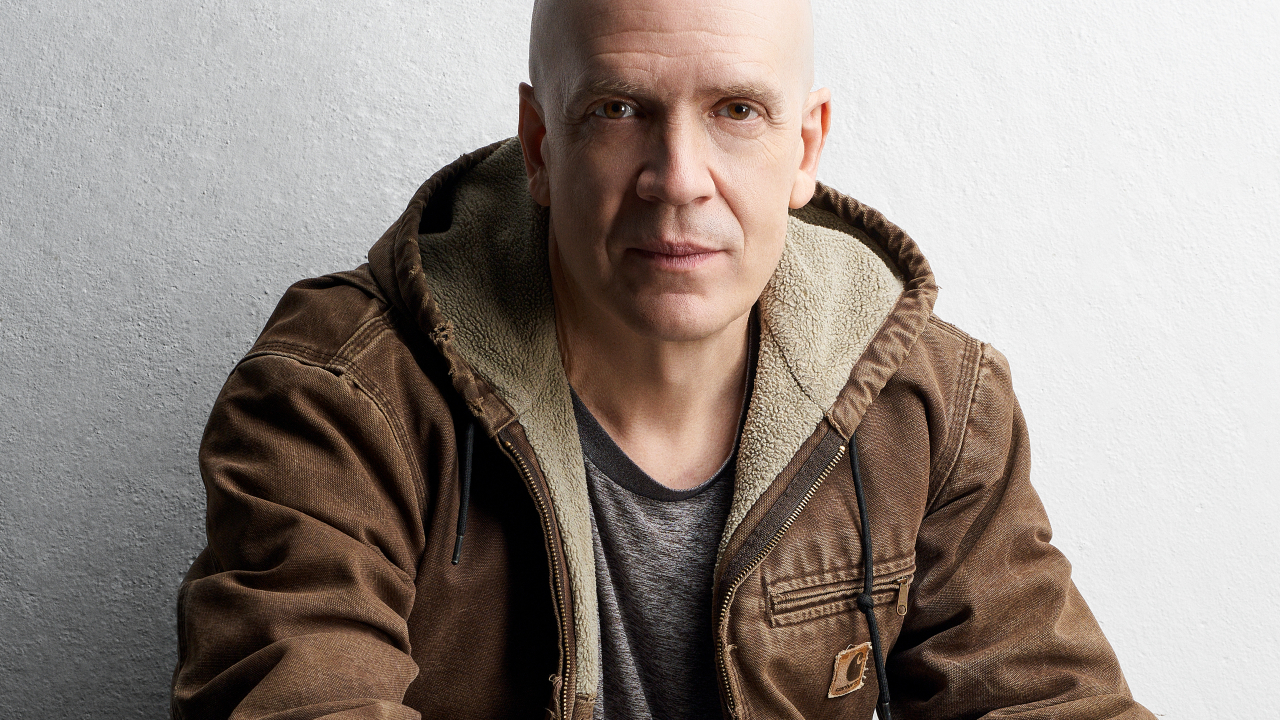

Article continues belowAlbert Ball provides the inspiration for Brave Captain, the opening track on Big Big Train’s 10th album, Grimspound. David Longdon, Big Big Train’s singer, flautist and all-round multi-instrumentalist, vividly remembers first seeing the statue when he was just seven years old.

“Albert was a local hero,” says the Nottinghamshire-born Longdon. “My father was in the RAF, and he was the one telling me about this dashing young airman standing there. You have that triangulation – him, the statue and me. The song is a 51-year-old man looking at what a seven-year-old boy is looking at. I’m older, the statue is older, but Albert is still the same. It’s about the passage of time.”

As with so much of the band’s work, both Brave Captain and Grimspound itself delve deep into Britain’s past in search of forgotten folklore and lost heroes, turning reality into myth and vice versa. The subjects that they write about are in danger of being lost in the eddies of mainstream culture, saved only by the likes of Longdon and his bandmate, Big Big Train bassist and founder Greg Spawton.

We’re sitting in the Old Bank Of England, a beautifully grand pub on London’s Fleet Street, whose history stretches back to the 15th century. Reputedly built on the site of the shop owned by Sweeney Todd, the infamous Demon Barber Of Fleet Street, it’s precisely the kind of location you’d find in a Big Big Train song.

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Longdon has travelled down from Nottingham, and Spawton up from his home in Bournemouth. Geographical separation seems to be one of Big Big Train’s defining characteristics: guitarist Rikard Sjöblom lives in Sweden while drummer Nick D’Virgilio resides in Indiana (the eight-piece’s remaining members are based in Britain).

Physical separation hasn’t slowed down their work rate. Grimspound is the band’s second album in just over a year, following on from 2016’s Folklore. Where its predecessor drew musically and lyrically on the folk heritage of the British Isles, Grimspound returns to the band’s prog roots.

“We’re totally proud to be defined as a progressive rock band,” says Spawton, who founded Big Big Train in 1990 and has been steering it ever since. “Ten or 15 years ago it was the genre that dare not speak its name. Now there’s much less of an issue with that. For us, it’s a genre where you can let yourself run free, and that’s what we did on this album. Letting the songs play out and draw to their natural conclusion.”

What it does share with Folklore – and with every album since 2009’s The Underfall Yard, Longdon’s debut with the band – is a propensity towards ‘story songs’. Whether it’s Albert Ball in Brave Captain or the ghostly fireside tale The Ivy Gate (featuring a guest appearance from original Fairport Convention singer Judy Dyble), their most memorable songs are driven through historical or mythological narratives – or sometimes a conflation of both.

“Those songs dial into a great tradition of folk music,” says Spawton. “Folk music is based on story songs – and some of those are incredibly bleak as well. But even our story songs capture personal stuff as well.”

There’s a very identifiable Englishness to Big Big Train. It’s not the Englishness of Nigel Farage or crusty old colonels reading the Daily Telegraph in their conservatories (“We’re definitely not Little Englanders,” says Spawton firmly). Instead, it’s the Englishness of Peter Gabriel or nature author Robert McFarlane or comic book legend Neil Gaiman – fascinated by the past but conscious of the present, and proudly eccentric with it. It’s there in the music they play, in the imagery they use, even in the name of the band – it comes from a toy train set that Spawton played with as a child.

“People write about what they know,” says Longdon. “Psychologically, we all do. Being brought up in small-town England, you have this connection with the landscape and with communities.”

“And the weird thing is that it seems to connect with people who aren’t from England,” says Spawton. “There’s something about the songs that speaks to people who were brought up in, say, a mining town in Germany. There’s a resonance there for them too. England is a funny old place. Perhaps it’s because of the old empire days, but it does still speak to the world at large. Maybe our songs help to continue the impression that people have.”

There’s also another, more visual connection between Grimspound and Folklore: the image of the crow that adorns both of the album covers. It’s an image that brings together nature and ancient history, astrology and astronomy.

The song Grimspound was inspired by an ancient settlement on Dartmoor, itself named after the raven-carrying Anglo-Saxon god Grim (according to some experts, a nickname for Woden, or Odin in Norse mythology). It was written for Folklore, but didn’t fit in with the themes of that album and the band held it over for the follow-up, as Longdon explains.

“Sarah [Ewing, cover artist for both albums] painted the crow and she asked me, ‘What’s it called?’ And I thought, I said, ‘Grimspound.’ It’s such a brilliant name for a crow. It sounds like something out of Gormenghast. And the crow has always had a lot of symbolism – in certain folklores, they’re the carriers of souls. They travel between the lands of the living and the lands of the dead. And they can bring somebody back.”

“And there’s a constellation, Corvus – the crow – which ties in with astronomy and astrology,” adds Spawton. “Astrology is the idea of As Above, So Below – the stars affect our destiny. The Corvus constellation will somehow affect things.”

The web of interconnecting stories and mythologies that Big Big Train have created for themselves is a gloriously vivid realm. But it could also be viewed as a bubble they have built around themselves to keep the real world at bay. It’s an idea that both men shoot down instantly.

“When you write about the past, you are writing about the modern world, because we are people of our time,” says the singer. “It’s very hard not to be engaged in the 21st century. I think it’s riveting what’s happening at the moment within the world. Amazing stuff. Off-the-scale stuff.”

So why not write about it directly?

“Well, we do obliquely,” says Spawton. “A Mead Hall In Winter, on the new album, is about the Enlightenment – 150 years of deep thinking that led to modern democracy. But it’s also despairing of how things are now. That was The Age Of Reason. Now we’re in The Age Of Unreason. All the stuff that’s out there at the moment… there’ll be a tax on free speech soon. But there are different ways of tackling it. You can do it in a Roger Waters-style, head-on. The danger there is that you alienate people, and one of the purposes of music is to bring people together. But you can draw on past lessons to write about current affairs, without alienating people or dating it. If we wrote an album about Brexit or Donald Trump, in 10 years’ time it would be a period piece.”

It’s a fair point. And it’s not as if Big Big Train are completely disconnected from the real world. They’re engaged enough to be aware of the pitfalls of the modern music industry, keeping all the important things in-house, whether that’s releasing their records themselves or forgoing a traditional manager. It’s not inaccurate to call them a cottage industry – one that’s had an extra wing added here and there over the last few years.

“We’re a fortified cottage industry,” says Longdon with a laugh.

“A castle industry,” adds Spawton. “I think five or six years ago we would have shied away from that description. I wouldn’t want to have revealed so much of that side of things. But it’s strengthened our band immeasurably to have total control. Plus you’re not being bled dry by a record label.”

That control extends most noticeably to the band’s approach to live shows. In August 2015, the band played three spectacular shows at London’s Kings Place – their first public gigs in 17 years. The shows, recorded and released as A Stone’s Throw From The Line, bagged them a Prog Award in 2016 for Best Live Event (they picked up another award the same night for Band Of The Year). The group will build on those appearances with another trio of shows at London’s grand Cadogan Hall this September, plus they’re currently in talks to appear at the Night Of The Prog Festival in Loreley, Germany in 2018. Are this once gig-shy band unexpectedly about to turn into a global touring monster? Apparently not.

“It takes a lot of planning and economics to put on our shows,” says Spawton. “We tend to hire expensive venues, our drummer lives in America, one of our guitarists lives in Sweden, so you have to fly people over and find somewhere to rehearse where you can accommodate eight people plus a string section, plus a brass section. And it’s got to be good. Anything we do live costs a fortune.”

“We could play the Frog & Trumpet every Thursday,” says Longdon. “But we probably wouldn’t get many people after a few weeks.”

It’s probably for the best that BBT have no plans to transform themselves into a live behemoth. Their plates are full enough as it is with Grimspound, plus the ongoing Station Masters project, which sees the current line‑up revisiting tracks from the band’s distant past. And then there’s the upkeep of the magical-realistic world they have built and continue to build. The future – just like the past – is bright.

This article originally appeared in issue 76 of Prog Magazine.

Art Attack

Prog speaks to Big Big Train’s cover artist Sarah Ewing to discuss her stunning artwork for the band.

The striking art of Grimspound and its predecessor Folklore come courtesy of artist Sarah Ewing. She first connected with the band in 2015, when Greg Spawton asked if she was interested in producing the artwork for the Wassail EP.

“I was delighted as I was a huge fan of English Electric Part 1 and 2,” she says today. “We kicked off with the two main images used on the Wassail EP: the front cover and the green man. At this time we also looked at developing the crow motif.”

The Cotswolds-based artist’s work is inspired “by my rural environment and sense of connection to the land… a sense of place and the stories therein”, as well as BBT’s music. “The songs always have a strong narrative. It’s up to me to present and express those stories visually. Greg, David and myself spend a lot of time discussing the themes. We pass each other relevant reference material, drill down on what’s trying to be said. Once they feel we’re all on the same page, I go and get my pencils out.”

The crow that appears on both album covers – also named Grimspound – represents a meeting of minds. “I’ve used crows in my work for many years,” she says. “They are a potent symbol of the middle ground between the natural world and a more ethereal one. They’re intelligent, resourceful, linked to many folklore narratives, both dark and light. It fits the band really well.”

The cover also features the constellation of Corvus – aka the crow. “Having spoken to the band about their themes for the new album, I felt drawn to look at old astrological charts and maps, and also to research antique instruments of measurement and navigation. The sense of exploration seemed to fit well with this album – whether on land or sea, or somewhere a little more heavenly.”

See www.facebook.com/SarahLouiseEwing for more information.

Big Big Train premiere Experimental Gentlemen

Big Big Train - Grimspound album review

Big Big Train's Greg Spawton gives us a glimpse into his prog world

Dave Everley has been writing about and occasionally humming along to music since the early 90s. During that time, he has been Deputy Editor on Kerrang! and Classic Rock, Associate Editor on Q magazine and staff writer/tea boy on Raw, not necessarily in that order. He has written for Metal Hammer, Louder, Prog, the Observer, Select, Mojo, the Evening Standard and the totally legendary Ultrakill. He is still waiting for Billy Gibbons to send him a bottle of hot sauce he was promised several years ago.