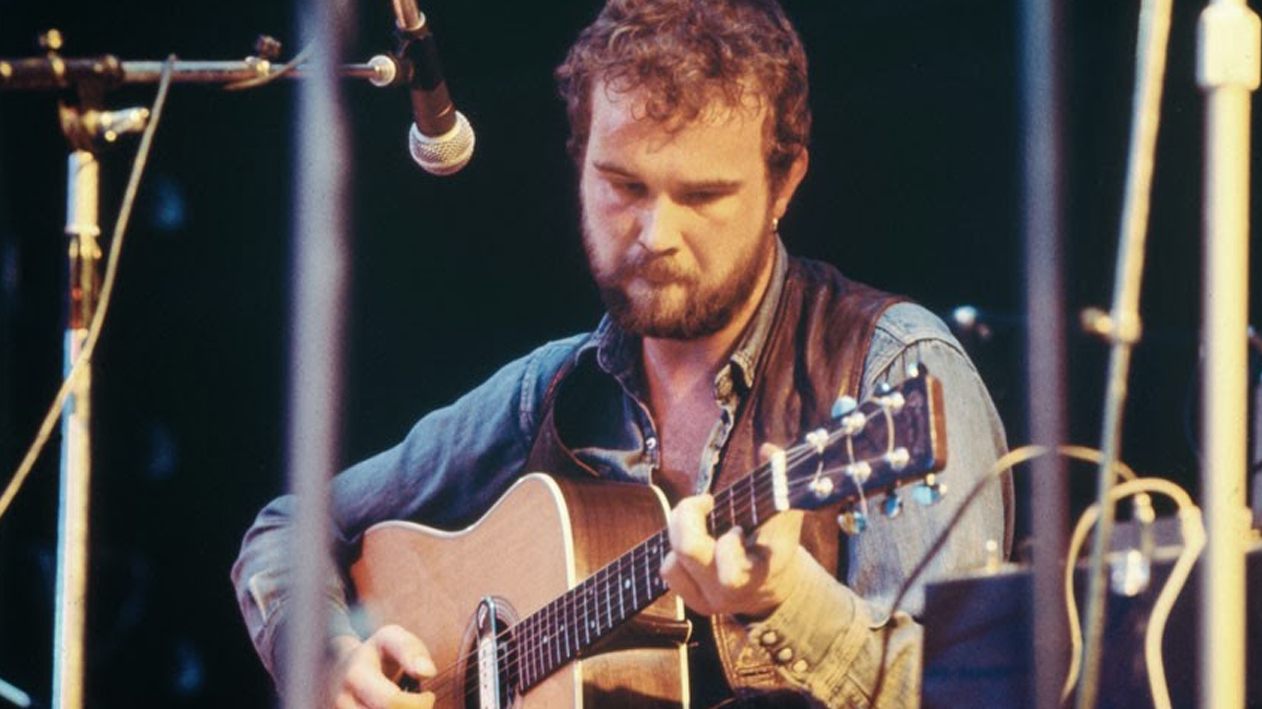

Bearded men with acoustic guitars always appeared to be the antithesis of prog: by their very nature, folkies seemed to be making regressive music, retreating to “tradition”, to rootsiness. They also seemed to epitomise that most nausea-inducing spectacle: the sensitive young man, the lonely boy outsider, the bedroom poet who can’t get a girlfriend and tells the world so in dreadful, self-pitying verse. Who among us has not guffawed uproariously at the scene in National Lampoon’s Animal House when John Belushi, descending the stairs to find some anaemic beatnik with an acoustic guitar serenading a girl with a sensitive folk ballad, seizes the guitar and smashes it savagely against the wall? Who among us hasn’t wanted to do the same to the whey-faced, bum-fluffed fun-annihilators who produce their bloody 12-strings and start picking out Neil Young’s The Needle And the Damage Done at parties?

Growing up in Glasgow in the late 70s and early 80s, one of the party favourites of the acoustic guitar and scraggy beard massive was John Martyn’s May You Never, a haunting, Celt-tinged blues ballad from his classic 1973 album Solid Air. You probably heard it murdered many times by some flat-voxed James Taylor wannabe before actually hearing the original.

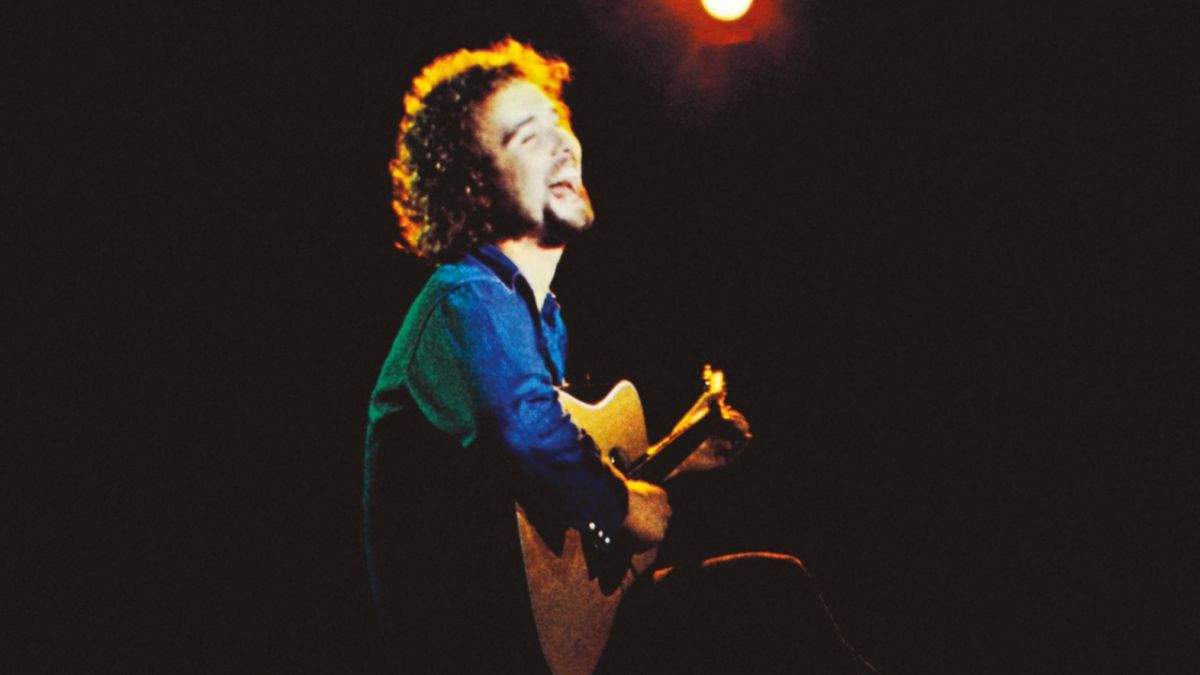

Your reporter, then, was probably not alone in having, for many years, an unreasonable prejudice against Martyn based solely upon those who sought to interpret his work. This prejudice, like so many, was a stupid one that was happily blasted to pieces in 1978 when he performed Big Muff from the astonishing One World album in a live film for The Old Grey Whistle Test. Fed through a labyrinth of effects pedals, it sounded like the madder end of dub, it sounded like music that had more in common with Can than with any of the rootsy folkies that I then so detested. It was one of those what-the-fuck?! moments that we have all experienced upon being confronted with music that blows our minds. Man.

And any preconceptions that Martyn was some knock-kneed, introspective bedroom wallflower were soundly destroyed a year later when he headbutted my mate in a bar in Glasgow.

Martyn had been enjoying a small sherry after dinner, as it were, and my pal had, metaphorically speaking, spilled his pint. Martyn drew his head back and cracked him on the nose. There was blood. Soon, after a few minutes spent tearing lumps of flesh from each other’s faces, Martyn put him in an armlock and rammed him face-first into the wall. “Stay the fuck down, cunt!” he growled in the sort of Glasgow accent that can loosen the bowels. My chum, slumped in a heap, was no longer in a position to argue. At which point one of the bar staff tried to calm John down and get him to leave. Martyn grabbed him by the throat: “You want some too, ya fuckin’ fanny? Do ye?” The hapless pint-puller acknowledged that he did not, in fact, want some or indeed any. Martyn slowly released him and was led out of the bar.

Twenty minutes or so later he was onstage at the Glasgow School of Art and we were in the audience, my friend still pressing a wet towel to his now-ruined nose. Martyn was mesmerising in a performance that I remember clearly: much of the material was drawn from One World, at times spacey, dub-crazed, at others jazzy and late-night. May You Never had the hairs on the back of everyone’s necks bristling. In a month when I also went to see The Pop Group, James ‘Blood’ Ulmer, Kevin Coyne, Suicide and Pere Ubu, Martyn’s was the most disconcerting and memorable show. Was it really 30 years ago? Well, Jesus.

Afterwards I saw him and bass player Danny Thompson and my busted-nosed friend sitting together in the bar. All pals together after some eye-to-eye apologies and manly handshakes. Martyn was by now very convivial, a beardy uncle, telling us about his trip to Kingston, Jamaica, to record at The Black Ark with Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry (“Now Scratch, he is really fucking mental, by the way,” said the pot of the kettle) and recommending that we listen to Pharoah Sanders and Davy Graham. We did. He also said he’d come and see our band the following week. He didn’t, of course. Probably just as well. He’d probably have kicked fuck out of us for crimes against music.

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Martyn was many things. He was actually a sensitive poet, though a proper one, firing off autobiographical despatches from a life that was happy but knew more than its share of sorrows. He was a Glasgow hard man when it suited him, though he was born Iain David McGeachy in New Malden in Surrey and spent only part of his early childhood in Scotland. He grew up in the respectable South Side of the city, brought up by his father and grandmother. Still, to outsiders, when he lapsed into that Glasgow snarl which he sometimes did, he may as well have been the Razor King from the violent streets of the Gorbals.

When he was in his teens, Martyn straddled the sub-cults of beat and mod, dressing like a tramp to go to folk clubs but donning a sharp suit on a Saturday night to go to the dancing with his girlfriend.

Glasgow had a thriving folk scene in the 60s, thanks in part to the influence of the great Scottish traditional song revivalist Ewan MacColl and the active encouragement of the Communist Party who had decided that this was authentic people’s music in opposition to commercial trash like rock’n’roll.

By 1965, a new generation – Martyn among them – inspired by Dylan was discovering folk music. New clubs, particularly Clive Palmer’s Incredible Folk Club in Sauchiehall Street, catered to this less traditional traditionalism. Clive’s group The Incredible String Band, regulars at the club in 1965, were already starting to branch out and experiment with other ethnic musical sounds. Martyn was a contemporary of the ISB as well as Billy Connolly and Bert Jansch. His biggest inspiration and mentor was the now largely forgotten Hamish Imlach, who taught Martyn to play blues guitar and allowed him to play the odd song of his own between sets. At 17 he was a prolific writer and performer, though hadn’t seriously thought of music as a career.

Like many Scots, Martyn permanently migrated south of the border almost as soon as he had the bus fare. He started playing in folk clubs in London, then a meeting with label boss Chris Blackwell resulted in his becoming the first white artist to sign with Island Records, until then best-known as a UK outlet for Jamaican bluebeat, ska and reggae. John’s 1967 debut album London Conversation is a fairly standard folk album of the time (mostly self-penned, obligatory Dylan cover) though the flute and sitar on Rolling Home hint at a more expansive sound to come. His voice had yet to develop into the slurred instrument that he said was his attempt to sound like a tenor sax.

The second album The Tumbler was still more adventurous, thanks in part to the happy fusion of Martyn’s pastoral songs with jazz flautist Harold McNair’s ethereal woodwind sound. But John was dissatisfied with his recorded output.

“I got bored with the folk/acoustic thing. Churning that out stifles innovation, kills the personal touch,” he said.

In 1970 John was hired as guitarist on an album by Beverley Kutner that was to be produced by Joe Boyd, who had been instrumental in the success of Fairport Convention, The Incredible String Band, Pink Floyd and Nick Drake, who would become a close friend of Martyn’s. John and Beverley became an item, began writing together and released the subsequent album Stormbringer! as a duo. Stormbringer! marks a big departure for John. It was the first time he used the Echoplex on his guitar, a sound that would become his signature. On the next album, The Road To Ruin, Martyn fell out with Boyd over the multiple overdubs. He also worked with a band for the first time, one that included his long-time collaborator bassist Danny Thompson, a muso for hire who had worked with The Incredible String Band, Fairport Convention and Pentangle. Thompson moved John in a jazzier direction, becoming the perfect foil for Martyn’s guitar and voice. They worked together right up until John’s death earlier this year.

John began to experiment with effects pedals, feedback and keyboards. He collaborated widely, most notably with Steve Winwood of Traffic, Free’s Paul Kossoff, Richard Thompson, late of Fairport Convention, improvisational jazz drummer John Stevens, and Phil Collins and bassist John Giblin who were then working together in Brand X.

The music became free ranging, from the complex 1973 classic Solid Air (written about the decline of Nick Drake,who would die the year after its release) to the echo-laden 1977 masterpiece One World. Island boss Chris Blackwell became a close friend and encouraged Martyn in his collaborations. Other Island artists like dub producer and certifiable genius/madman Lee Perry worked with John, a fruitful if unlikely combination. While in Jamaica he played on Burning Spear’s roots reggae classic Man In The Hills as well as some sessions with Lee Perry and Max Romeo. He later claimed that he was paid in Tia Maria and porn films.

He was no record company darling. Chuffed with the success of Solid Air, Island received the follow-up Inside Out anticipating more of the same, some nice mellow, pastoral jazz folk. What they got was about 40 minutes of wild electronics, free jazz and vocals that sounded like a drunk in space. In retrospect, it anticipates the Island era of Tom Waits nicely. But at the time, to put it mildly, it was totally misunderstood and critically panned. Martyn had a serious disregard for the press ever since.

Martyn’s music was not difficult in the sense of being unapproachable. It was definitely ‘progressive’ by any definition. Not all of it: much that was recorded after 1980’s harrowing Grace And Danger was conventional by comparison. He was always a great songwriter, though, and songs covered by Eric Clapton, Dr John and Wet Wet Wet probably earned him far more in royalties than any of his own recordings.

Martyn never settled into a comfort zone. In the 90s he signed with then hip-

as-fuck label Independiente. His 1996 album And saw him experimenting with trip-hop and drum & bass. Later he made an album of startling covers called The Church With One Bell, where he played music by Lightnin’ Hopkins, Portishead, Dead Can Dance, Elmore James, Randy Newman and others. And on his 2000 album Glasgow Walker he abandoned the guitar and wrote the whole thing on keyboards.

The last time I spoke to him, interviewing him around the release of the CD box set Ain’t No Saint in 2008, he was still wildly enthusiastic about music, chuffed to bits that Pharoah Sanders had asked him to work on a new album, and generous about younger bands. He was also talking about releasing music on the internet.

Sadly, now that he’s dead, there’s an almost inevitable process of rediscovery and reassessment going on, not unlike the cult which grew up around Nick Drake.

“I don’t want to talk about Nick. It’s creepy, ghoulish and strange; this lionisation is too late when you’re dead. If they’d dug him enough then, he’d still be here now. I’ve often thought of faking my own death and watching the record companies fucking drum up all the shit they can,” he told Classic Rock in 2000.

So beware of cashing in on his incredible legacy: if there’s one guy who would get so pissed off up in Heaven that he’d jump back down to Earth and stick the heid on you, it’s definitely him. Definitely.

Allan McLachlan spent the late 70s studying politics at Strathclyde University and cut his teeth as a journalist in the west of Scotland on arts and culture magazines. He moved to London in the late 80s and started his life-long love affair with the metropolitan district as Music Editor on City Limits magazine. Following a brief period as News Editor on Sounds, he went freelance and then scored the high-profile gig of News Editor at NME. Quickly making his mark, he adopted the nom de plume Tommy Udo. He moved onto the NME's website, then Xfm online before his eventual longer-term tenure on Metal Hammer and associated magazines. He wrote biographies of Nine Inch Nails and Charles Manson. A devotee of Asian cinema, Tommy was an expert on 'Beat' Takeshi Kitano and co-wrote an English language biography on the Japanese actor and director. He died in 2019.