The story of Tim Bowness' Lost In The Ghost Light

Tim Bowness examines the changing nature of the music industry and popular culture through his fictional rock star who has fallen from grace

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

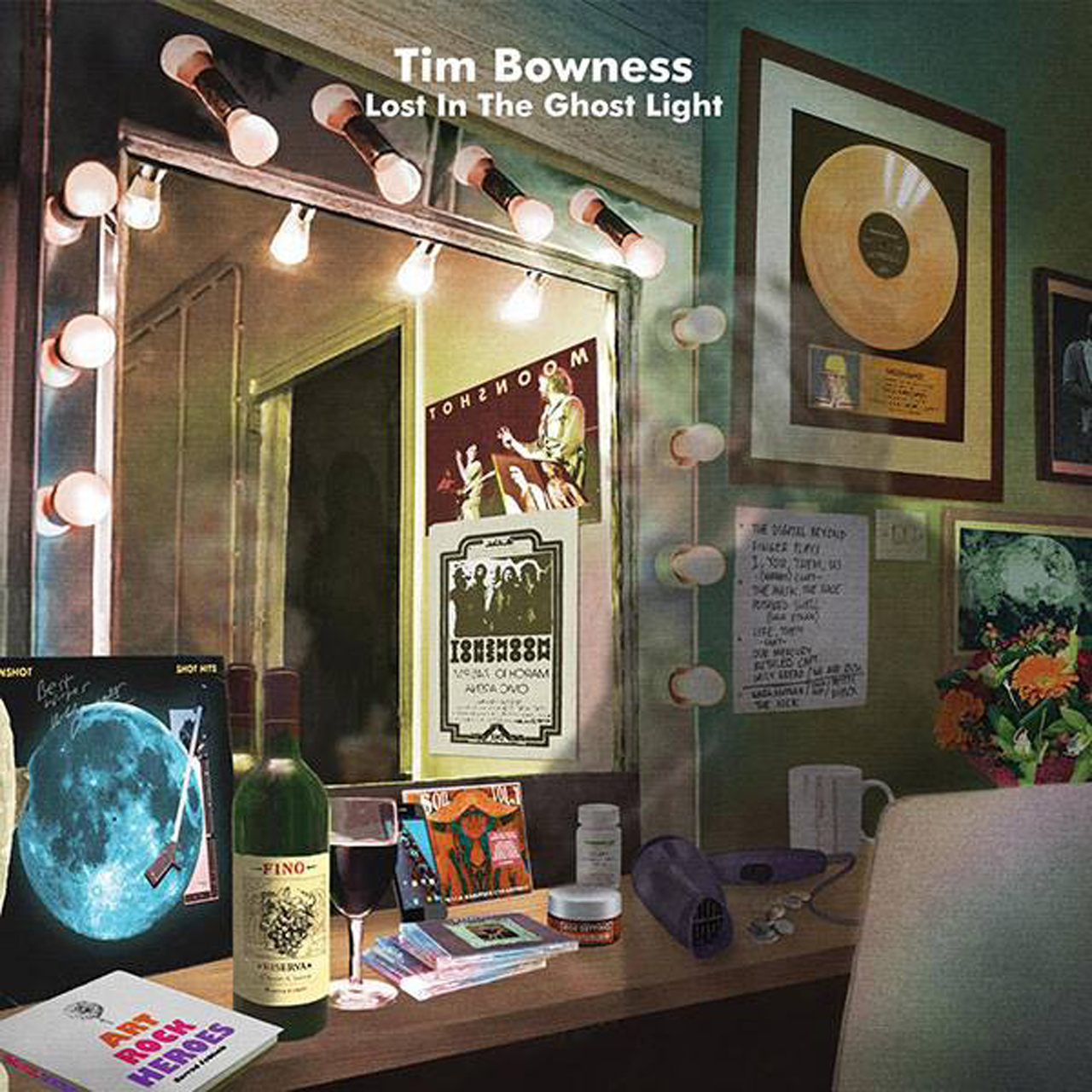

“It’s a fascination with a particular era of music, a fascination with a particular era of music-maker,” says Tim Bowness about Lost In The Ghost Light, his new concept album that tells the story of a once-adored rock star facing his musical mortality as his career enters its final act.

Much of Bowness’ own musical journey has been a history of partnerships – the No-Man duo with Steven Wilson, Memories Of Machines with Nosound’s Giancarlo Erra, and co-piloting Henry Fool alongside Stephen Bennett. After releasing one album under his own name in 2004, My Hotel Year, Bowness’ solo career began in earnest with Abandoned Dancehall Dreams in 2014, which was initially conceived as the follow-up to No-Man’s 2008 album Schoolyard Ghosts.

“It was something I discussed with Steven Wilson and we were set to do it,” says Bowness, “but then eventually Steven was too busy with his solo career and said, ‘Look, I think this is mainly you anyway so why doesn’t it become the start of your solo career?’”

Working alone proved inspiring. “I found a voice while making the album that was quite different from my voice in No-Man, from my voice in Memories Of Machines or other projects I’ve been involved in,” he says.

Stupid Things That Mean The World followed in 2015, setting the stage for Lost In The Ghost Light, where Bowness examines the changing nature of the music industry and popular culture through his fictional rock star who has fallen from grace.

“There are people from that late 60s and 70s creative explosion who retained their idealism, their vision, but equally there are people who, due to commercial pressures or collapsing family lives or merely disinterest and indulgence, lost their way,” he says.

“In some ways, I was trying to map a progression of music through a particular type of musician who would have felt very threatened by the late-1970s punk and New Wave explosion, one who would have suddenly felt perhaps irrelevant after being feted. Certainly, I’ve met musicians who this happened to, very good musicians who were completely derailed by the process, actually felt worthless because of the press abandonment and who questioned the nature of their own work.”

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Although Lost In The Ghost Light is a solo release, Bowness wanted the music to have the feel of a band behind it. “I’ve been restricting myself to certain sound palettes,” he says. “With a lot of solo projects they can be quite diffuse, so for me, from album project to album project, I wanted them to be very focused in terms of the sounds used, the musicians used and the way it comes across as a coherent, almost band-oriented whole.”

He also didn’t want to release a sprawling, unfiltered flood of music. “I was very aware that when you’re working on your own, indulgence is a possibility so perhaps I’ve been far stricter on myself than I would be even in collaboration. I’ve been anticipating criticism and I think when you have a very specific idea of what you want, let’s say on a particular vocal take, nothing else will do.”

This pursuit of the perfect take meant that on two songs, Moonshot Manchild and You’ll Be The Silence, more than 50 hours went into realising the final vocal track. “Left to my own devices, part of the problem is that yes, 50 hours can go on one particular vocal take,” Bowness admits. “But this is not the case for all of it. A couple of tracks on the album were pretty much first or second takes and I knew they worked and so there was no questioning, there was no point in going back. It wasn’t about technical perfection: it’s more about the feel that you want for the song, the expression for the song. If I wasn’t hitting what I heard in my head, I would do it again and again.”

Bowness drew upon the talents of an impressive group of players to craft the band‑oriented sound he was after, with Henry Fool’s Stephen Bennett on keys, bassist Colin Edwin, Pineapple Thief’s Bruce Soord on guitar and the drumming talents of both Hux Nettermalm and Andrew Booker, plus guest appearances from two prog legends, Kit Watkins and Ian Anderson. However, they were never all in the same place at the same time: everyone recorded their parts remotely.

“On the previous two albums I’d assemble a band in the studio, we’d perform and then whatever we did was subject to post‑production and the occasional overdub,” says Bowness. “In this case it was almost exclusively sending files. The interesting thing is that having done both approaches, quite often it’s difficult to tell the difference. I’ve not found it particularly restrictive compositionally, nor have I found it restrictive in terms of what you can then do with the material, because sometimes you can still take it into unusual places based on the contributions that are coming in remotely because something might suggest two or three new ideas.”

Despite being a self-confessed fan of both Watkins and Anderson, who plays the featured solo on the track Distant Summers, Bowness says he never felt star-struck about asking them to contribute.

“When you’re making music, no, I don’t think you ever feel like that, but actually I’ve got say in these cases I didn’t really need to. Certainly, with Ian Anderson, I have to say he did what I wanted and beyond. It was just a wonderful solo and the moment where the fanboy kicks in is when you’ve got the completed piece and you listen to it and you think, ‘That’s Ian Anderson playing on my piece!’ There’s a real sense of astonishment. The 15-year-old you would be in awe of this moment and, in fact, the present you is in awe of this moment as well. That never goes away.”

In terms of maintaining artistic control over his creations, Bowness has the enormous benefit of co-running his own label and outlet, Burning Shed. Once again, however, he’s keen to point out that this happy circumstance isn’t a recipe for self-indulgence, but a further impetus to apply strict quality control.

“One of the benefits of Burning Shed is I was always quite bloody-minded and idealistic in terms of what I did, and I think it has made me more bloody-minded and idealistic because I don’t have to put these things out,” he says. “These things that are going out are very much a labour of love for me, and I’ve always favoured the classic 40- to 45-minute album statement, partly because I think there’s something in that in terms of the concentration of creativity and the concentration of a listener’s attention span that works. Even in the early days of No-Man, in the CD age, when we were signed to labels like One Little Indian and Epic in the early 1990s, I would insist on our albums being short because I felt that although the CD was a fabulous medium in some ways, it did encourage waste; it did encourage indulgence that there’s 70 to 80 minutes of time.

“There was a period of incredibly padded-out albums – and that’s not to say there aren’t great, classic double albums because of course there are, and certain music benefits from it. Ambient music, for example, is absolutely liberated when it’s outside of the 40-minute restriction. But for me, with song albums and rock albums, the statement is often more potent if it’s more focused and curtailed.”

Despite the introspective feel of Lost In The Ghost Light, Bowness says it isn’t intended to be autobiographical – rather, he was inhabiting a character as he wrote the album.

“What’s interesting about that is it was no less emotional and seemingly no less personal,” he says. “Of course there are elements of my own experience, whether it be people that I’ve met or experiences I’ve witnessed, that are a part of it. There are a couple of lyrics on the album that a couple of older musicians of my acquaintance – I won’t mention who – said, ‘By God, that’s me!’”

Although there’s no formal overarching ‘trilogy’ theme linking the three records that Bowness has released under his own name since 2014, all of them share the virtue of being conceptual. “I’ve found increasingly as I’ve made albums that I can write songs in isolation, but generally speaking, it only truly feels satisfying when I have a larger theme to work towards, something that excites me. I find that brings out unexpected qualities because you have this end goal in sight and this overall atmosphere and theme.

“In a sense, it’s more like working towards the novel than a series of short stories. That is one thing with the three albums: they do have overriding themes. The difference with this is it’s slightly more narrative and specific in that it’s very much about a particular character, time and subject, but again I find sometimes that limitations both in terms of sound and theme can actually produce more creative and intense work. Bizarrely, you find you can better yourself in some way or do something that surprises you through trying to actually fully realise that singular theme.”

But will any of this material ever be performed live, perhaps even as a complete concept piece? “It’s very difficult to do musically,” says Bowness, “and also it’s how it would be presented as a stage show. Although I’ve always been a huge fan of bands who have used theatricality, whether it be The Who, Kate Bush, Pink Floyd or David Bowie, in my own work I’ve always been more interested in emotionally presenting something on stage with no distractions. So I don’t know. In a way this would almost suggest something theatrical and certainly something larger scale, so it’s something I’d have to think about seriously if I was considering taking this particular album on tour.”

For Bowness, the classic model of record-tour-repeat doesn’t apply, meaning he has a different relationship with his music compared to his progressive predecessors, even as he confronts the musician’s equivalent of post-natal depression.

“Once you’ve actually created something and finished it to your satisfaction, there’s always a tremendous slump,” he says. “In some ways you do everything you can for the album. You put yourself into it for quite a long period of time and then you eject it from your system and try to immerse yourself in something else that excites you as much.”

Don’t expect Bowness to stumble into a creative slump any time soon though – he’s already working on new music and, unlike the unhappy protagonist of Lost In The Ghost Light whose peak has long since past, Bowness is just hitting his stride.

This article originally appeared in issue 74 of Prog Magazine.

After starting his writing career covering the unforgiving world of MMA, David moved into music journalism at Rhythm magazine, interviewing legends of the drum kit including Ginger Baker and Neil Peart. A regular contributor to Prog, he’s written for Metal Hammer, The Blues, Country Music Magazine and more. The author of Chasing Dragons: An Introduction To The Martial Arts Film, David shares his thoughts on kung fu movies in essays and videos for 88 Films, Arrow Films, and Eureka Entertainment. He firmly believes Steely Dan’s Reelin’ In The Years is the tuniest tune ever tuned.