“I remember Nick Mason saying, ‘Pink Floyd is stopping… we’ll leave him to do the big outdoor concerts now!’” But Jean-Michel Jarre argues: “I want to contribute to tomorrow, not yesterday”

Pioneer’s life and times include predicting that electronic music would change the world by thinking “not in terms of notes, but as music that you do with sounds and noise”

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

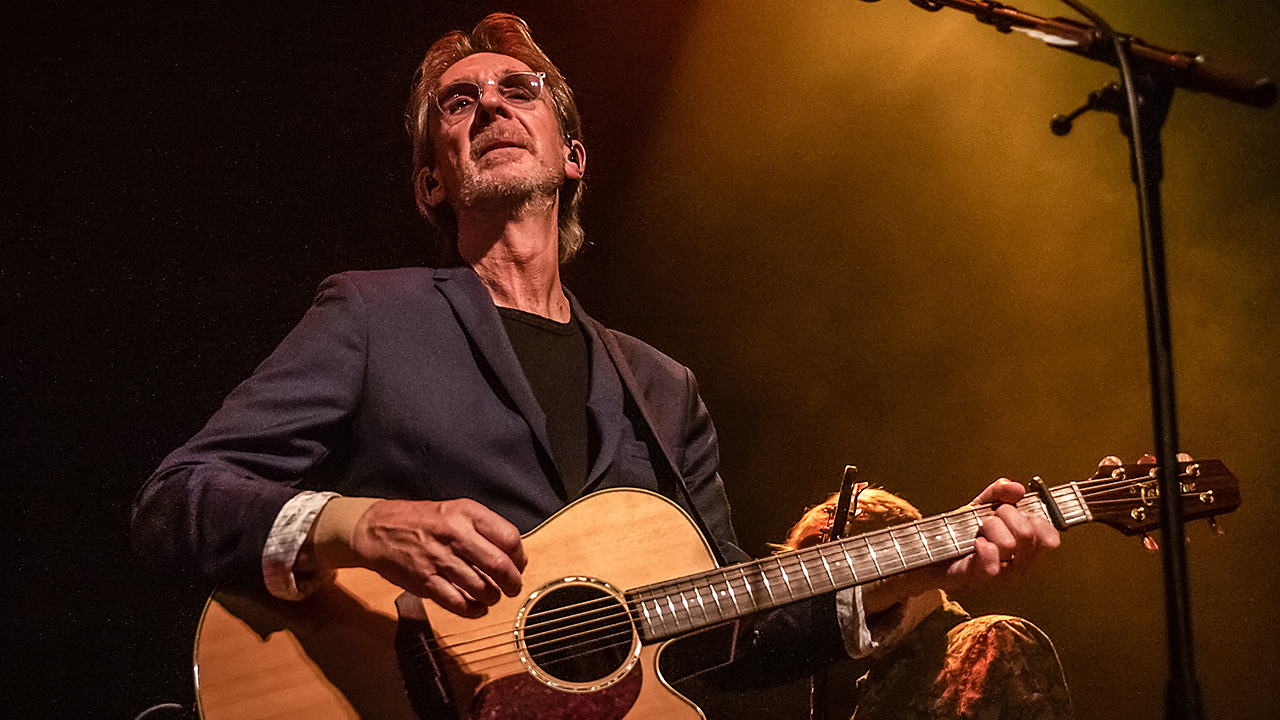

Jean-Michel Jarre’s collaboration on a track with ex-CIA “whistleblower” Edward Snowden was grabbing headlines as his new album Electronica 2: The Heart Of Noise emerged in 2016. It followed the previous year’s Electronica 1: The Time Machine. Like that album, which featured Pete Townshend, Tangerine Dream and John Carpenter, it’s an eclectic set of musical hook-ups with young and veteran like-minds, from Gary Numan to The Orb, from Pet Shop Boys to Hans Zimmer. Speaking about the Snowden cut, Jarre, a ridiculously young-looking 67, told Prog: “It strangely reminded me of my mum, who was a great figure in the French Resistance. She taught me that the line between a traitor and a hero is quite subjective and fragile…”

Jarre’s life story was fascinating even before he found fame. His father Maurice Jarre was a giant of film music who won Oscars for his Lawrence Of Arabia, Doctor Zhivago and A Passage To India scores. Yet Jean-Michel barely knew him. “That was out of the picture,” he responds when Prog probes his musical genes, in the only terse moment in an otherwise chatty, convivial interview.

The young Jarre studied music at the Conservatoire de Paris and had Pierre Schaeffer (father of “musique concrete”) as a mentor, spending time working at Stockhausen’s studio.

Falling in love with synthesisers, he set up his own makeshift “studio” in his kitchen. There, in 1976, he recorded his third album, Oxygène, which struggled to find a release. When it did, despite sneering reviews, it sold 12 million worldwide. Equinoxe, two years later, was followed by a Place de la Concorde concert which drew a million-strong crowd, placing Jarre in the Guinness Book of Records. He went on to surpass that with 1.5 million in Houston in 1986, and then 2.5 million, again in Paris, in 1990. In 1997, he attracted 3.5 million in Moscow. His shows became orgies of futuristic, sci-fi spectacle, replete with lights, lasers and fireworks. The 1988 shows on floating stages at the then-desolate London Docklands, subjecting his fan Princess Diana to apocalyptically bad British weather, are carved in London folklore.

Jarre’s now sold over 80 million albums and was the first Western musician officially invited to play in China. It’s safe to say that his electronic/ambient/trance/New Age music – while, at heart, is closer to experimental than commercial – “translates”.

Off duty, he hasn’t been dull. He married Charlotte Rampling, his second wife, in 1978. They separated almost 20 years on, and Jarre, after a high-profile romance with Isabelle Adjani, was married to another actress, Anne Parillaud, for five years from 2005. So it’s been quite a life, but the man previewing his album to assembled guests in a chic London club today has the demeanour of a bright-eyed enthusiastic newcomer. He’s evidently thrilled with the latest work.

Settling down with Prog, he says he’s so eager to hear feedback that he wishes he could ask questions rather than answer them. He soon remembers that’s not how the “oxygene” of publicity works, and relaxes into discussing his deceptively left-field music, his links with the moon, his visual extravaganzas, and his symbiotic relationships with prog, Krautrock, cinema and art. He describes his track with The Orb as “a spacey Pink Floyd vibe meets a Marcel Duchamp collage”, while Hans Zimmer is “my only serious competitor for collecting modular synthesisers”. Then there’s the matter of NASA naming an asteroid after him…

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

The album is a lot to take in; there are so many different sounds and styles. Yet overall it feels more contemporary, more 2016 than some might expect.

That’s interesting. Having spent so much time in the studio, for five years with the two albums, I wanted to create something that took a journey through all of electronic music but could be perceived as very much now in terms of production and sounds. This was one of my dogma from the beginning. Utilising the mixing, the digital sounds, it’s something that wasn’t possible for me only 10 years ago. Now I consider digital sounds able to compete with the warmth and precision of analogue.

Where it’s getting interesting these days is we now have digital instruments that do things analogue instruments cannot. It’s something else. You have virtual synths now which can make sounds a Moog or classic synth cannot. I took great care with the production because I worked with people from different generations. Every day I asked myself: “What is the right sound for today?”

When you collaborate, do you have to reduce your ego? Or give it free rein? When you’re used to being in full control?

I didn’t think about this during the process, because it went very naturally. Perhaps for different reasons with each artist. On my side, I went, OK, I have to prepare this exercise by composing something in the function of the artist I want to collaborate with. I did a piece of music based on the fantasy I had of that artist, from their music.

I remember a discussion I had with Pete Townshend in the early stages. I said: “Y’know, I’ve done something with electronic instruments which are my fantasy of you and The Who.” Because from Baba O’Riley from Who’s Next, Pete had been the first to integrate synthesisers into rock music. But then I left enough space, so that he could go into that space, could be a lyricist, could sing, could do some processed guitar riffs – and it was an immediate connection. Because I left the maximum of space for, not the ego, but the personality, the talent of these artists to enter.

And on the other side, every artist told me – and this was a surprise – that this was my album, and that I had the final cut. Obviously they wanted to hear the final mix and mastering, but they trusted me, they let me produce it the way I wanted to. So that’s the reason I think it has a coherence. I spent a lot of time trying to create a kind of invisible link between tracks, so it wasn’t a compilation. There’s an overall colour, I think.

When you were young, you were a painter. Does that come into the colours in your music?

Yes, I’ve always been heavily inspired by visuals. When I started electronic music I had no references, because nobody before was doing it. So my influences were coming from movies: 2001: A Space Odyssey and all the great sci-fi movies. But also Italian and French movies from the 50s and 60s, like Fellini. And the bright pop colours of Technicolor, as well as the black and white of Fritz Lang’s Metropolis. Then later on, abstract painters like Jackson Pollock or Pierre Soulages. They were also inspirations for me, and for my visuals…

Those live shows of yours are historic, bordering on legendary. They were immensely popular spectacles, which hog the Guinness Book Of Records for attendance figures. Do you ever look back on those nights and wonder if they really happened?

Absolutely! When people ask about it, I think – was that me? Did I really? We’re talking about me? Because it was so… impossible to describe. I felt so privileged. Having so many followers, an audience like that. From the first one, I started to think about the visualisation of electronic music. How it could be brought onto a stage. Because it’s not the most sexy thing to stand on your own before your laptop or keyboards for two hours onstage. Or to stare at your gear. So I thought about involving visual techniques of my generation, with electronics and videos and lights and lasers and all that. It was quite a prominent shift. Because in those days, even in rock and roll, you didn’t do that.

I mean you had, probably, Pink Floyd and myself. In those days, even big bands, U2, the Rolling Stones and bands like that, were just playing with some lights and that’s all. Then later they embraced the whole visual concept. And obviously the whole electronica scene now, when I see Tomorrowland or some other festival, I see things

I was doing 30 years ago. Which is fun! I loved rave, at first, because it was like my early concerts – hijacking a place then changing this place forever, so it was never the same afterwards. Like my show at the Docklands…

Everyone in London has a story about your ’88 Docklands shows, despite the biblical rain. Do you remember it vividly yourself?

Yes, to tell you the truth I think I’ll write a book about it one day. Because behind the scenes it was an absolute… saga. So many things were involved. From the police, from some religious sects… and also Princess Diana.We were quite friendly and she was a fan of my music. She’d said to me that next time I played in the UK, she’d be there. She said, “The Docklands? No problem, I’ll be there.” But – if people remember now – it was in the middle of nowhere then. It was just being built up at the time.

So now we had to build a Royal Box, for security reasons, and the whole thing got outrageous. The Royal Navy got involved, because suddenly this canal, which was usually so calm, like a lake, became as choppy as the Atlantic, with big waves and everything, because there was a storm. The Navy said the stage had now to be legally considered a boat, and everybody must wear a safety jacket. So then we had the London Symphony Orchestra wearing safety jackets. It was all so ridiculous and crazy. It was totally off the system.

Off the system?

Yes! That phrase fits, because when I think now about all my collaborators on these two recent albums – they might be very popular, big name legends, or they might be beginners, but they are all slightly off the system. Different. Outsiders! That’s the word. I could have called the whole project Outsiders.

When Oxygène broke in the 70s, it sounded like music from the future. Although you talk about outsiders, in a way electronica has become the predominant music of the 21st century. What was the future is now the present. Did you ever, back then, think it would become so successful and familiar a sound?

Personally, I had no idea. But I was convinced that electronic music was going to change the world. That’s why I was involved at that early stage. For one very simple reason: it’s not like punk or rock or hip-hop, it’s not a genre of music. It’s simply a different way of approaching music composition. By considering music for the first time not in terms of notes, but as music that, basically, you do with sounds and noise. That changed the whole perception of how to approach music. We all became sound designers. A DJ today is a sound designer. Music is like cooking. Our job is cooking frequencies and wave forms in a very organic, sensual way. This sound’s simmering, this sound’s boiling…

Didn’t you once say you wanted your music to sound like going to the Moon?

Yes! It’s interesting how electronic music has been linked with space and the future. Even if I never tried for it. My music at the time was maybe aiming for space, but more between the ground level and the clouds. Like, 10 metres above the Earth. Not “outer” space…

But it’s funny, how I’m linked to space. I became a very good friend of Arthur C Clarke after he wrote 2010: Odyssey Two, the sequel to 2001…. I was a big fan of the first book. I remember I bought 2010… in London, and was surprised to see my name in the acknowledgements, because he wrote it while listening to my music. I said: Wow! So we started a correspondence, before the internet, before emails – and became friends. He said, “You know Jean-Michel, you’re going to play on the Moon one day!” I said, “Come back to Earth, Arthur, it’s not possible!” He said, “Ah, maybe not today… but you should project something onto the Moon while you play, that’s possible…”

And then I did this concert in Houston involving NASA, and also there was the tragedy of Challenger… when I was linked with the Space Centre. Later on I did the concert in Moscow with the Mir station, live, and I discovered that the cosmonauts were playing one of my albums, Equinoxe, in space. They said it was their favourite music to listen to up there. So there’s always been this connection, without me pushing for it.

Was progressive rock an influence on you? You mentioned Pink Floyd, and your music has prodded the boundaries…

Absolutely. I always felt a connection with early Pink Floyd. We were the first two, probably, to start doing audio-visual statements in our concerts. I remember once Nick Mason saying, “Oh no, Pink Floyd is stopping, we’ll leave Jean-Michel to do the big outdoor concerts now…”

There’s a big link between prog rock and electronic music anyway. The early electronic acts in Germany, Can and Tangerine Dream for instance, they were prog rock acts first. When I worked with Edgar Froese (from Tangerine Dream), I mentioned that we’d started out around the same time. Edgar said, “No, you started in electronic music before us, because when you started we still existed as a prog rock band.” Well, Phaedra and Ricochet came out before Oxygène, so he was being modest, but still. I was talking with Bobby Gillespie on the plane from Berlin to London yesterday, and he said Primal Scream are a “prog rock punky noise band”. There are links everywhere. Prog has locked into people like Nine Inch Nails, with an industrial touch, where it’s linked to sound processing. And of course Krautrock, with its hypnotic, trance-y feel, I’m linked with that…

Indeed.You were a sculptor of repetition, motifs, almost of mantras, on your early work…

Oh yes, and you can find this too in Indian music, in Terry Riley, in jazz, in Philip Glass. Repetition as a motif. I mean, the guy who invented it was Johann Sebastian Bach. He was the king of sequences! And we all owe so much to Pierre Schaeffer, who in the late 40s was the first one to say music should be done with sounds and noises, not only notes. He was recording loops, playing with speeds and reverses, while working on 78s… before even tape recorders! Frippertronics, the Fripp and Eno thing? Schaeffer was doing that 30 years earlier! When I studied music as a kid, this is what we were doing. We were taught that electronic music really comes mainly from Germany and France, with Schaeffer, Stockhausen – nothing to do with American pop or blues. And when John Foxx presented me with an award a few years ago, he pointed out that British musicians had been colonised by American sounds, but then Oxygène sounded like a fresh notion of European roots.

Do you feel distinctly European?

Well I have a lot in common with England, a country I love deeply. The mother of my children, Charlotte Rampling, is English, and my kids are half-English half-French. But I always kept my French accent! I love the pride that Great Britain has as a nation. There’s nothing bad about that: the opening ceremony of the 2012 London Olympics was just the perfect example of how a country should promote itself. Faithful to its values, but also rebelling against itself. I love the subversion. Yes, I feel European, but also – it’s a bit cheesy to say – a citizen of the world, because I travel so much. But I relate to the Pet Shop Boys’ lyrics, they remind me of my roots in Lyon, my home town. The frustrations and emotions of poor people, rich people – it’s universal but has a special European resonance.

Did fame change your view of the world at all? Some high-profile romances made you a tabloid target…

Frankly, no. I’ve been lucky. When I became successful and all that, being married to an extraordinary woman in Charlotte, we had and still have a fantastic complicity and relationship. We’ve always been quite remote from this. I always considered fame or success, like failure, to be an accident in life. That’s what we teach our children. Don’t be trapped by success or so-called failure like a rabbit in the car lights. A simple philosophy, but true.

While the Edward Snowden track has been causing a stir, wasn’t there talk of a David Lynch collaboration? Did that fall through?

Well, he was the very first to respond to the project, he’s been very nice. I gave him three tracks, and he mixed them all together as one track! So then I worked on it, but we both agreed it was… not really appropriate. And then he was starting work on Twin Peaks. We said we’d maybe work on it again after Twin Peaks is finished. So we’ll return to this later on. Hopefully.

You’re playing some big festivals and shows of your own this year. Can we expect spectacle?

I’m working on it! The problem is that people are expecting so much visual stuff, because of my past. Festivals are “communist” concepts, where all the acts have to deal with a similar canvas, so I’m trying to find a solution to that. I hope I’ll have an exciting, cinematic production which we can transport without 40 trucks! But after five years in the studio, the whole idea of opening the window is such a shock to me already. I just hope it makes sense for 2016 – I want to contribute to tomorrow, not yesterday.

You’re the first man I’ve met who’s had an asteroid named after him…

Yes, but… it’s quite an ugly one! It’s not a beautiful stone. Anyway, it’s kind of an achievement, I guess. It’s number 4422. I was in NASA, and when they told me they’d given it my name I was quite proud. Although I’d rather it kept its distance; we don’t want it coming too close to us. It’s OK where it is. Where he is. Or where she is. I must find out whether it’s male or female. Its shape makes it difficult to say…

Chris Roberts has written about music, films, and art for innumerable outlets. His new book The Velvet Underground is out April 4. He has also published books on Lou Reed, Elton John, the Gothic arts, Talk Talk, Kate Moss, Scarlett Johansson, Abba, Tom Jones and others. Among his interviewees over the years have been David Bowie, Iggy Pop, Patti Smith, Debbie Harry, Bryan Ferry, Al Green, Tom Waits & Lou Reed. Born in North Wales, he lives in London.