“The telegram read, ‘You’ve got to come back – your record is in the Top 20.’ I thought, ‘What Top 20?’ We couldn’t understand”: Why Peter Baumann thought Tangerine Dream were weird...

With new solo album Nightfall and a new edition of Phaedra both on sale, the synth maestro says limited ability, cutting-edge gear and raw luck led to success in the 70s, and regrets running out of time to reunite with Edgar Froese

Tangerine Dream fans can rejoice in not just the 50th-anniversary reissue of Phaedra, but also a new album from one of its creators. Synth maestro Peter Baumann makes a welcome return with Nightfall, which continues his ongoing exploration of the human condition. He tells Prog why he prefers to do things in haphazard ways, and why he wishes he’d managed to work with Edgar Froese again.

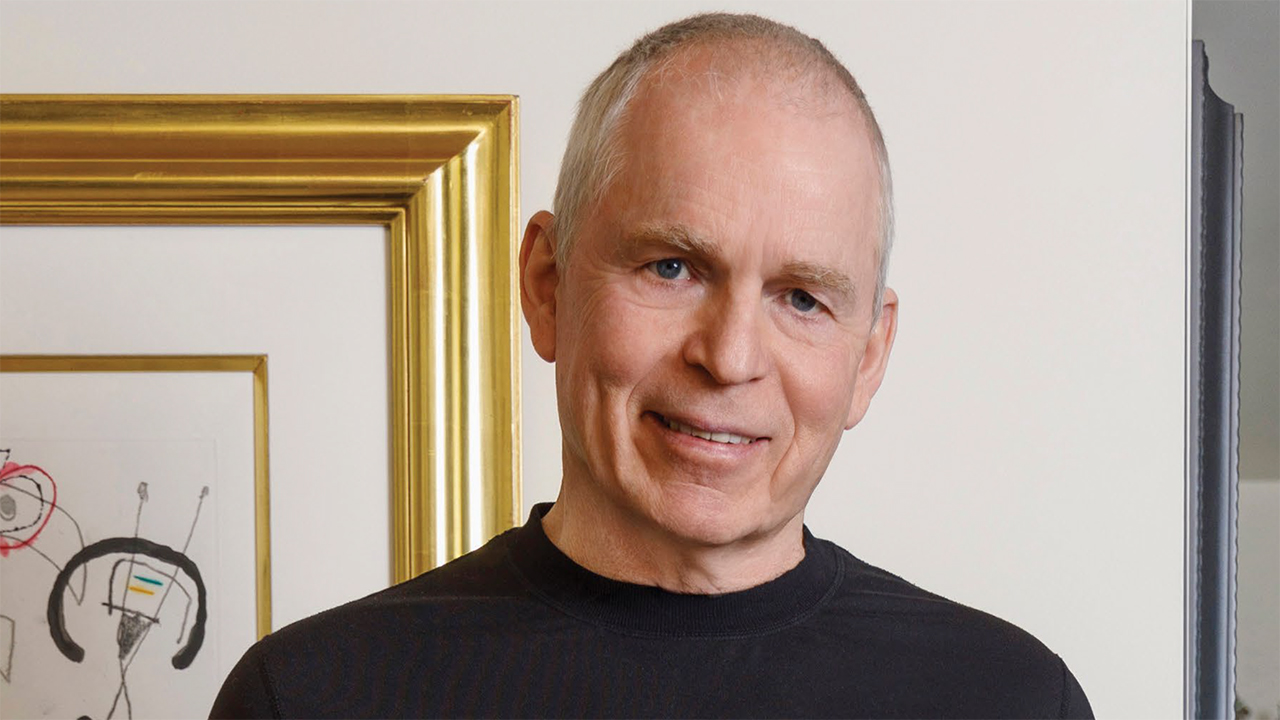

“I’ve never considered myself to be a good musician,” says Peter Baumann. “I’m not a good keyboard player, but the upside is that you reach for more ways to express yourself. It’s all intuitive; it’s all creative. My whole life I’ve never felt like doing what you’re supposed to do. I’ve always kind of moved in haphazard ways.”

Haphazard or not, Baumann’s journey through music is a pretty distinguished one. As a member of Tangerine Dream during their imperial 70s phase, he helped advance the Berlin School of electronica, creating avant-garde music forged from the twin poles of technology and free improvisation. When he quit in 1977 – leaving behind a run of hugely influential albums – he applied a similar working approach, albeit on a less grand scale, to his solo career.

“I would say that the feeling, where it comes from, has stayed the same,” he says. “In Tangerine Dream it was about making the expression as direct as possible. We’d record things like a mattress falling onto a cymbal, then turn it backwards and put it through a phaser. We’d record whale sounds on a Mellotron tape and then treat them. Whenever we played any kind of melody that sounded conventional, we’d change it. It was always about expansion; about transcendence.”

Baumann’s engagement with music has wavered at times. By the new millennium, having sold his new age label Private Music (sometime home to Tangerine Dream, among others), he'd forsaken it altogether. In 2009 he set up the Baumann Foundation, a think-tank exploring “the experience of being human in the context of cognitive science, evolutionary theory and philosophy.” That dovetailed with his activities as part of the California Institute of Integral Studies and the not-for-profit Mind & Life Institute.

It wasn’t until 2014 that he returned to music, building a basement studio and putting together a few songs. Naturally, Tangerine Dream weren’t too far from his thoughts. He and Edgar Froese reconnected. “I’d planned a trip to Vienna to start working with him,” Baumann says. “We spent a little bit of time together in the studio. But when I was planning my next trip, Bianca [Froese’s wife] told me he’d passed away.

“Edgar had always wanted to work together again, but he was busy with some things and I was busy with others, so the time was never quite right.I would have loved to have made more music with him. There was a very interesting chemistry between Edgar and myself – his way and mine were very complementary.”

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

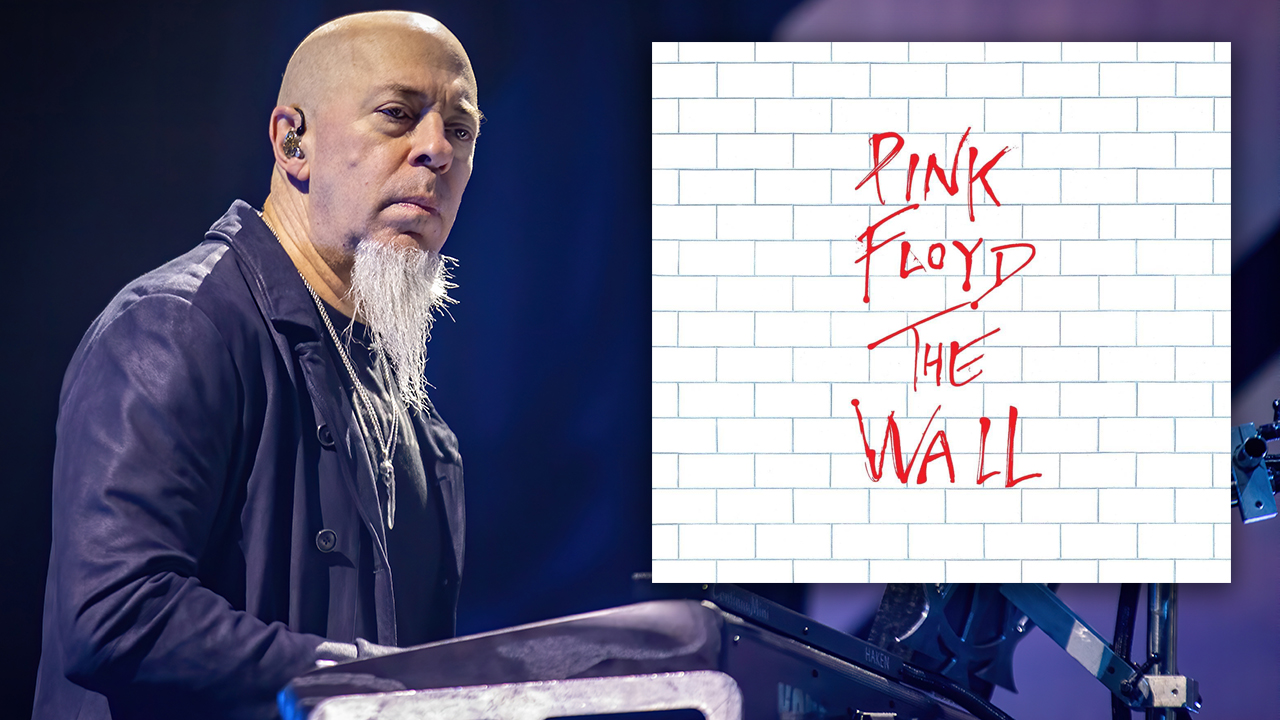

Baumann then channelled his creative energies into 2016’s Machines Of Desire, his first solo album for decades. Soon Paul Haslinger, keyboardist and guitarist with Tangerine Dream from 1986 to 1991, got in touch. “He said he’d been listening to Machines Of Desire and would love to work together,” Baumann recalls.

“Paul is a real musician – he really knows how to play the piano – and I’m not. But the advantage is I can play melodies that don’t always land on the beat – I kind of drag it over the beat – and I play unusual sequences. He brought a degree of sophistication and I brought more of an unhinged quality, a little off the beaten path.”

The resulting collaboration, Neuland, came out in 2019. For a while afterwards, it looked as though Baumann had retreated from music once again. But now comes a fresh solo product in the shape of the compelling Nightfall. As with his previous work, it’s an instrumental album rich in atmosphere and mood, a series of endlessly mutating soundscapes that convey something mysterious and intangible.

“I always keep some sketches around,” he says. “I already had a couple of ideas when I was working with Paul, then I started developing them properly about a year and a half ago. The idea was an album that’s relatively quiet – no fast rhythms, no aggressive melodies, but very moody. I let all the pieces grow organically. They all influence each other and they morph; it’s like a garden that keeps growing.”

There are a lot of parallels between philosophy and music, and my default is always the balance

That sensation of music in constant flux is reflected in the song titles: Lost In A Pale Blue Sky, On The Long Road, From A Far Land, Sailing Past Midnight and so on. Nothing sits still for long, if at all. Woodblock rhythms slip in and out of ambient guitar figures; slow synth waves are permeated by monastic choirs; muffled subterranean beats underpin lines of woozy piano; eastern percussive vibes are punctuated by shrill sax. The title track feels akin to Vangelis’ Blade Runner soundtrack – all austere synths and gliding cityscapes.

Baumann points out that such tendency for motion “is my go-to mood. It’s always been towards the ephemeral, the transient, the otherworldly, moving. Instrumental music lends itself very well to that kind of expression. I tried working with lyrics many years ago, but words immediately trigger some kind of association. Without lyrics you have much more of a differentiated feeling. For instance, if you have a song about sitting on a beach with your lover, you’ll have a specific idea of that. With instrumental music, that doesn’t happen.”

For him, the value of instrumental music is that you never hear a piece the same way twice. “This is where music and philosophy come together: you can go to a restaurant and it’s never the same meal, even if you order the same thing. Taking a walk through the park is never exactly the same – we’re influenced by how well we slept, how well we ate, what’s on our calendar. So nothing is ever really still. There are a lot of parallels between philosophy and music, and my default is always the balance.”

So is he constantly discovering new things about himself through music? “The patterns and the big picture don’t change, but the specifics do,” he replies. “The philosophy behind it is that we only feel something in the actual moment. You can’t really compare how you felt in the past; you only have a memory of that feeling, and that’s different.”

We started to play and I couldn’t hear anything. The PA wasn’t switched on! We didn’t even have a professional roadie

Constructing Nightfall saw Baumann adopt the creative strategy in the studio that he’s always utilised. “I like to work on a track, step back for a couple of days, or maybe even a week, then come back to it. You hear it differently that way. Even going back to [solo debut] Romance ’76, I did that. I was working on different pieces, revisiting them and rebuilding them a little more each time.”

The release of Nightfall roughly coincided with a belated 50th-anniversary edition of Tangerine Dream’s groundbreaking, sequencer-driven Phaedra. Their first album for Richard Branson’s Virgin label, it notched up six-figure sales in the UK and nestled inside the Top 20 – a feat made all the more remarkable given that it received only minimal radio airplay.

Baumann isn’t given to nostalgia, but the six-disc reissue – featuring a full recording of the band’s first-ever UK gig at London’s Victoria Palace Theatre in 1974 – inevitably prompts a few memories. “I was on holiday in Italy with my girlfriend when I got a telegram from Richard,” he recalls. “It read: ‘Peter, you’ve got to come to London. Your record is in the Top 20.’ I thought, ‘What Top 20?’ The idea that our music could ever reach any kind of chart was never on our radar. We couldn’t understand it. Then suddenly here we were, having a limousine pick us up at the hotel.

“I remember very vividly how we started to play at the Victoria Palace, and I couldn’t hear anything out of my side of the PA. Then I realised it wasn’t switched on! We didn’t even have a professional roadie. But I loved the setup there. There were a lot of people – it was very dense, but it was also very intimate. I look back on all that very fondly.”

When the three of us were together, it felt like there was something extra in the room, like a fourth player

He reflects: “The best concerts we had were when we would get completely lost in a track and lose sight of how long we’d been playing. Between Edgar, Christopher [Franke] and myself it was just a unique combination. None of us were brilliant musicians; but it was the time, the instruments that were available, and a lot of luck in many ways. It was truly three individuals with music as the main focus. When the three of us were together, it felt like there was something extra in the room – like we had a fourth player.”

Much like Baumann the solo artist, Tangerine Dream worked by intuition.“There was never any discussion before we went into the studio. The band that Edgar had played in before was much more conventional, but with us he totally broke from that and used the guitar in very unique ways. He enjoyed that I didn’t try to play conventionally. Sometimes I rolled my eyes at what Edgar would do and say, and sometimes he’d react the same way to me. But that tension made it interesting.

“I never felt that we were part of the progressive scene – we were more into electronics and Ligeti, more obscure music. That formed most of our inspiration. We would just call our music ‘weird.’ I think our closest link to popular music was Pink Floyd’s The Dark Side Of The Moon. At the time, that was also considered to be pretty far-out.”

I’ve never planned for the future. There’s no rhyme or reason to my life

His final album with Tangerine Dream was Sorcerer, the soundtrack to William Friedkin’s 1977 action-thriller. And while the band spent much of the next two decades immersed in further Hollywood soundtracks, Baumann preferred to operate in the margins. It’s essentially where he’s stayed ever since, making music on his own terms and in his own time.

There remains a purity to his creative drive, unspoiled by notions of commercialism. He has no plans to follow up Nightfall anytime soon – which is exactly as it should be in Baumann’s world. “I’ve never planned for the future,” he says. “There’s no rhyme or reason to my life; I’ve never known where it will go. When an idea strikes me, musical or otherwise, I’ll really go for it.”

Freelance writer for Classic Rock since 2008, and sister title Prog since its inception in 2009. Regular contributor to Uncut magazine for over 20 years. Other clients include Word magazine, Record Collector, The Guardian, Sunday Times, The Telegraph and When Saturday Comes. Alongside Marc Riley, co-presenter of long-running A-Z Of David Bowie podcast. Also appears twice a week on Riley’s BBC6 radio show, rifling through old copies of the NME and Melody Maker in the Parallel Universe slot. Designed Aston Villa’s kit during a previous life as a sportswear designer. Geezer Butler told him he loved the all-black away strip.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.