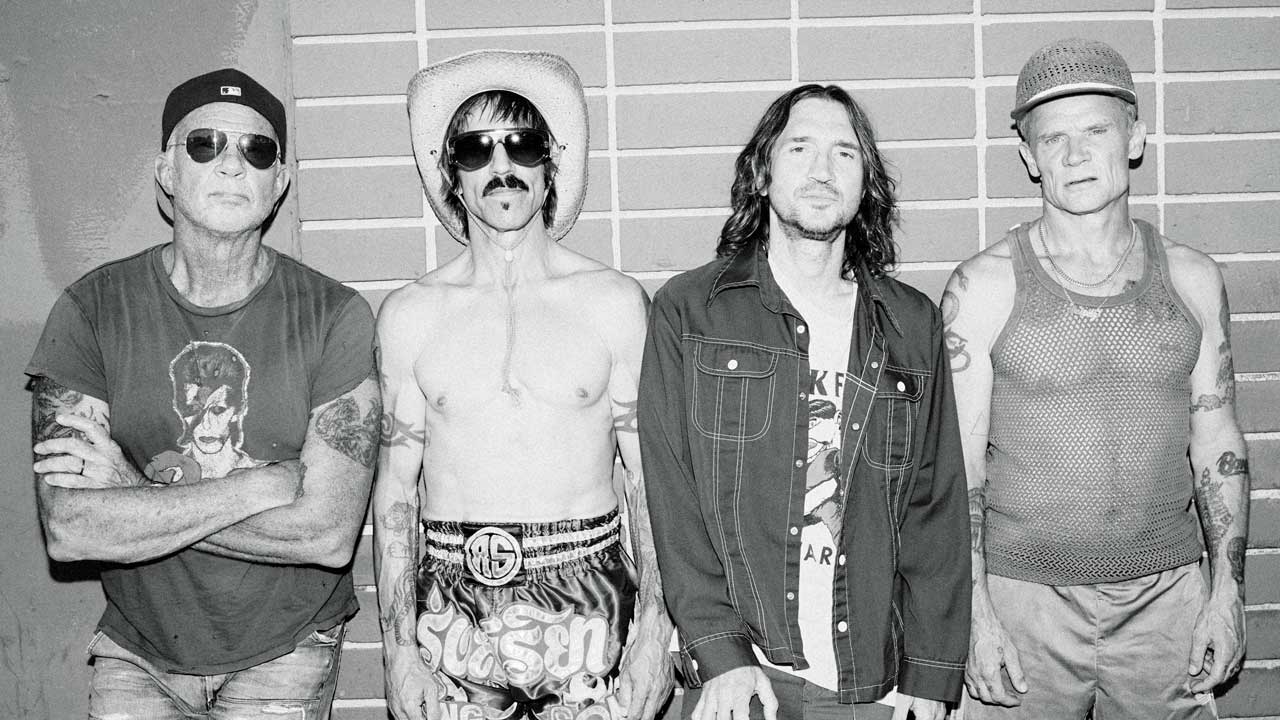

How the Red Hot Chili Peppers rediscovered their hot streak

With guitarist John Frusciante and producer Rick Rubin back on board for their new album, the Red Hot Chili Peppers are once again in the place where their best music is made

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

It was towards the end of 2019 when the conversation took place. Red Hot Chili Peppers bassist Flea was hanging out at home with his former bandmate John Frusciante, the prodigal-son guitarist who 10 years earlier had quit the band for the second time. Frusciante’s departure had been painful, sure, but ultimately necessary for both parties, and the two men had stayed in touch sporadically.

“We were just shooting the shit, talking, eating,” Flea says now of that evening. “We’d never really talked about it [the split] much. At one point my wife and his girlfriend were in the other room and we were sitting alone, and I said: ‘John, sometimes I miss playing with you so much.’ And I started crying when I said it…”

Suddenly his voice is thick with emotion. It’s difficult to tell for sure, but it looks like Flea is welling up.

“…And he looked at me and I saw the tears in his eyes,” he continues. “And he said: ‘I miss it too.’ There was just this moment, but in that moment I remember thinking: ‘Man, you know…’”

That moment was a tipping point. By the end of the year, Frusciante – the guitarist who played on the Chili Peppers’ most successful records – was a member of the band for the third time, replacing his own replacement, Josh Klinghoffer.

Frusciante’s return is more than just the latest twist in a sometimes combustible musical drama that stretches back almost 40 years. It’s a restoration of the finely balanced alchemical formula that powers one of rock’s most successful, innovative and occasionally misunderstood bands. The Red Hot Chili Peppers have made some great albums without John Frusciante, but they’ve made their greatest albums with him.

“If your long-lost family member comes back and says: ‘Hey, I wanna rejoin the family,’ you have no choice,” says frontman Anthony Kiedis. “You cannot say no.”

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

It’s early 2022, and the reconstituted (re-reconstituted?) Red Hot Chili Peppers are readying themselves for the release of their twelfth album, Unlimited Love. It’s a very Chili Peppers title, partly because it exudes exactly the kind of vibe they have long cultivated, and partly because it appears to be a reference to Love Unlimited, late soul titan Barry White’s backing singers in the 70s.

“It is not,” Kiedis says good-naturedly of the latter. He says it’s a lyric from a new song, She’s A Lover, that Unlimited Love producer and long-time Chilis collaborator Rick Rubin picked up on.

“I tried to fight it – ‘I kind of like these other titles I have,’” he says. “But it was titled by majority vote. That’s okay. I have faith in the group.”

Unlimited Love is a great album from a band whose ongoing greatness isn’t always fully appreciated. Sure, the Chili Peppers have been massively popular for the past 30 years: 1991’s Blood Sugar Sex Magik and 1999’s Californication have sold 15 million copies apiece, and songs such as Give It Away, Scar Tissue and Kiedis’s tender junkie’s mea culpa Under The Bridge are ingrained in the DNA of modern rock. But for some, there’s a part of the Chili Peppers that will forever have a sports sock dangling from its cock or be writhing in the desert covered in silver paint.

In reality, the Red Chili Peppers have got better, and certainly more interesting, with age. The punky, funk-powered rush of their earlier albums was exhilarating and ground-breaking (no other band sounded like them when they started in 1983, but plenty did by the end of that decade). But the music they’ve made this millennium has been complex and unique, straddling the various lines between rock, funk, pop, psychedelia and several other styles and sounds. None of the Chili Peppers are slouches musically, but in Frusciante they have had one of the greatest and most innovative guitarists of the past 30 years.

“I’ve never met anyone like John,” says drummer and resident “classic rock guy” Chad Smith, who, like Frusciante, joined the Chilis for 1989’s Mother’s Milk album. “He’s a dedicated person. He’s a hundred per cent in on whatever he’s doing. It’s contagious. It makes you want to bring your best too.”

What Flea didn’t know when he and Frusciante had their little moment together at the bassist’s house was that he wasn’t the only one wondering what it would be like to play together again. The band had begun writing songs for a new album with Josh Klinghoffer, but Kiedis felt something wasn’t right.

“It felt like we had lost a little bit of that eye of the tiger when it came to the urgency of making music and putting your heart on the line,” he says. “It had dialled down a couple of notches.”

The next time Kiedis and Flea met up, Kiedis was wondering if it was time to reach out to Frusciante.

“Flea, I have to tell you something, and it’s been on my mind,” he told the bassist.

“No, no, I have to tell you something that’s been on my mind,” Flea said. “It’s about John…”

Flea and Anthony Kiedis were both 15 years old when they met at Fairfax High School in central Los Angeles. Kiedis was the son of would-be Hollywood actor Blackie Dammett. Flea, born Michael Balzary in Melbourne, spent his formative years shuttling from Australia to America and back again before settling in LA with his mother and his abusive, jazz musician stepfather.

“When we were kids we had nothing,” says Flea. “We stole food to eat, we ran in the street, we were petty thieves, troublemakers…”

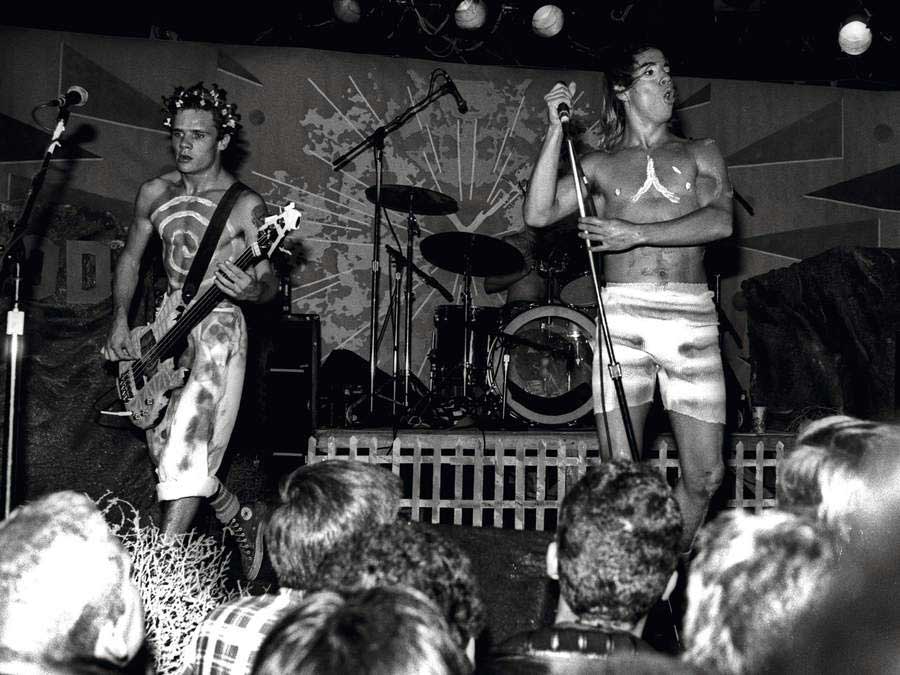

At least they were troublemakers with some sort of vision, and by early 1983 the pair had put together the first line-up of the Red Hot Chili Peppers, alongside guitarist Hillel Slovak and drummer Jack Irons, a couple of kids Flea had played in bands with at Fairfax.

There’s footage on YouTube of the Chilis’ very first TV appearance, on late-night talk show Thicke Of The Night in April 1984, six months before the release of their self-titled debut album. It begins with the youthful Kiedis and Flea, hair dyed purple and orange respectively, jousting exuberantly with host Alan Thicke, before the whole band launches into the livewire funk-punk of Get Up And Jump. They look like kids, but it’s not hard to see the men they are today.

“Oh my,” Kiedis says, laughing at the memory. “We were tiny little puppy dogs. I had a hard time looking at that broadcast in the moment: ‘Oh my god, we can be so much better than that.’ But now I see it and I think: ‘Holy shit, we were on fire.’ We did not have limiters of any kind.”

Even then, the Chilis existed in a state of chaos. Hillel Slovak and Jack Irons bailed before the band recorded their self-titled 1984 debut album (Slovak rejoined for the following year’s Freaky Styley, Irons returned in time for 1987’s The Uplift Mofo Party Plan).

“The pie chart of fun versus hard work versus craziness was more like a kaleidoscope,” Kiedis says of the band’s formative years. “It changed every day depending on how hungry you were, whether or not you had a place to sleep, what kind of addiction hole you had fallen down.”

Hollywood was the Chili Peppers’ playground. They were part of an arty punk underground scene that existed a world away, musically and spiritually, from the glam-metal movement clacking its cowboys boots on Sunset Strip a few miles west.

“We were definitely against the hair-metal scene,” says Flea. “We were, like, ‘Fuck them. We’re the underground, art-rock, get-weird east side guys; those guys are just rehashing Aerosmith and Kiss.’ In retrospect it was all petty bullshit. A lot of those bands were fucking great. Guns N’ Roses was a great band.”

Yet even back then there were more similarities than they’d care to admit. The Chili Peppers were just as fixated on sex and drugs as many of the bands they professed to hate: 1985’s leering Catholic Schoolgirls Rule and 1987’s Special Secret Song Inside (aka Party On Your Pussy) are as regrettable as their titles suggest, while Kiedis and Slovak were both nursing heroin habits to rival those of Nikki Sixx or members of Guns N’ Roses. For all their left-field cool, the Red Hot Chili Peppers were a committed party band.

“We were a party band, but you have to have something to bring to the party,” says Kiedis. “Flea was instrumental in saying: ‘We have to be good, we have to write some new shit, we have to have something to move these people.’ We always came fully loaded.”

Like every great band, the Chili Peppers were already stars in their own minds, even if no one else knew it.

“There was a certain arrogance,” as Flea puts it. “A ‘Fuck the world, fuck the system, fuck the authority, fuck the powers that be, we’re us and we’re doing our thing our way, we’re street kids’ thing. We were going hard and being wild.”

That arrogance didn’t translate into record sales, but it didn’t matter. The Chilis were kings of the Hollywood jungle.

“It didn’t dawn on us that there was something other than selling out clubs and making people happy and being original,” says Kiedis.

There was a cavalier romance to that period, but there was darkness too. Guitarist Hillel Slovak’s death from a heroin overdose in 1988 at the age of 26 momentarily stopped the party, and shocked Kiedis out of his own addiction, at least for a few years.

The band that released 1989’s Mother’s Milk was the same but different. Following Slovak’s death, drummer Jack Irons had quit, too shell-shocked to deal with being a Red Hot Chili Pepper any more. His replacement was a bandana-sporting rocker dude from Detroit named Chad Smith, who was told he could join the band only if he cut his hair. Smith’s refusal to do so was a show of obstinacy that impressed Kiedis enough to offer him the job.

Their new guitarist was an 18-year-old kid from West LA who considered himself the biggest Chili Peppers fan in town. His name was John Frusciante.

When John Frusciante joined the Red Hot Chili Peppers, he was the youngest member by seven and a half years.

“My brain was still forming,” he says. Back then he was shaven-headed and whippet thin, the band-mandated gurns he pulled in photos offset even then by an aura of intensity.

That intensity is still there. During our Zoom call, he alternates between laying on his back and looking up at the screen, and standing over it, looking down. He’s friendly but cagey, vocal in his discomfort with questions he deems too “personal”.

Frusciante was 16 when he saw the Chili Peppers live for the first time. It was, he says, a life-changing moment. “The energy was so intense that everybody there felt like they were part of the band,” he remembers. “It was like being on some kind of crazy drug trip for an hour, but I wasn’t on drugs.”

Frusciante had got to know Slovak, who he would eventually replace. Slovak once asked him if he thought the Chili Peppers would still be popular if they played the 20,000-capacity LA Forum. No, Frusciante had replied, it would ruin the whole thing. But the band he joined were on the verge of a massive step up that would eventually take them way beyond the Forum.

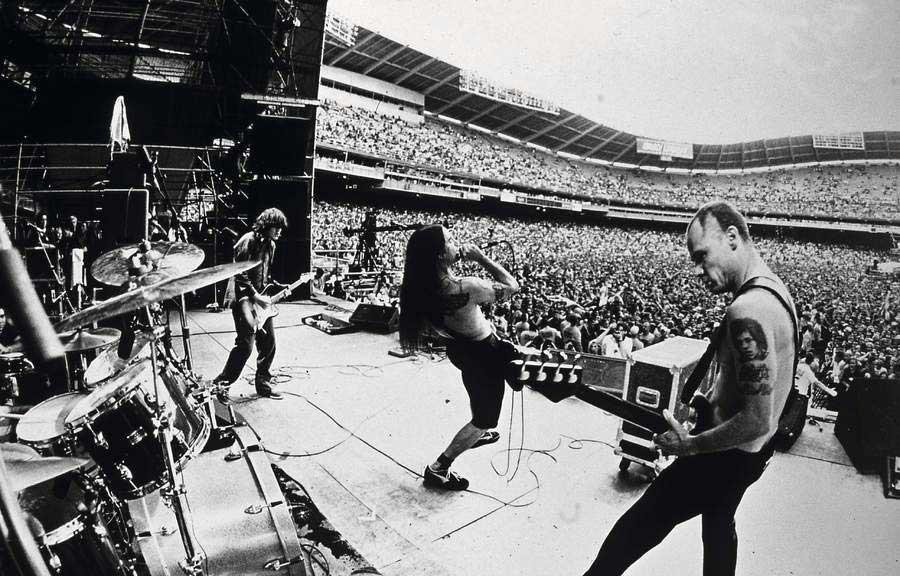

Their fourth album, Mother’s Milk, offset their grief at the loss of their friend with an indefatigable party spirit. It was the breakthrough they’d been waiting for, selling more than 500,000 copies in the US. Their next album was even bigger. Blood Sugar Sex Magik marked the first time they hooked up with producer Rick Rubin, a man whose touch turned everything to platinum.

That record was more than just the high-water mark for early-90s funk rock, it also helped bust the door wide open for the emerging alternative scene (it was a measure of the Chilis’ success that both Nirvana and Pearl Jam opened for them on the Blood Sugar tour, occasionally at some of the same shows).

No one in the band dealt with the pressures that came with that level of success.

“I became a mess when we got really famous,” says Flea. “I fell apart, I became ill, I had chronic fatigue syndrome, I was miserable and sad, and I went through a period of seclusion and sadness.”

Kiedis had his own issues: “I was confused by it. Then you have to go through a period of being an asshole. Anyone who has the impression that the world revolves around them is going to be an idiot for a while, and that happened to us all. And that really is no way to live.”

Frusciante handled it worst of all. His relationship with Kiedis was breaking down, and his drug use wasn’t helping. The kid whose new bandmates had nicknamed ‘Greenie’ a few years earlier because of his lack of experience with narcotics had begun to use heroin – another point of stress with Kiedis, who was fighting to maintain his own sobriety. Things came to a head in May 1992, when Frusciante suddenly quit the band after a show in the Japanese city of Saitama.

The Chilis had a rocky time following Frusciante’s departure. They tried a couple of ill-fitting replacements – Arik Marshall, who lasted a year, and Jesse Tobias, who lasted less than a month – before hooking up with former Jane’s Addiction guitarist Dave Navarro. That line-up made one album, 1995’s patchy One Hot Minute. The Chili Peppers were still a big deal, but they didn’t feel as vital as they had been.

But Frusciante had a much, much worse time of it. He began a descent into severe heroin, cocaine and crack addiction that left him physically and mentally wrecked. Most of his friends drifted away. His house burned down. Heavy drug use ruined his teeth, and his arms were left scarred from abscesses, a result of shooting up. He continued to make music, but it was as dislocated and ghostly as the man making it. “I was as close to dying as a person could be,” Frusciante later said.

But he didn’t die. By the spring of 1998 he finally entered rehab, where he began the journey back to health and sobriety. At the same time, the Chili Peppers knew their partnership with Dave Navarro was running out of road.

It was Flea who agitated to get Frusciante back in the band. Initially Kiedis resisted, but a tentative jam quickly led to a full reunion. The guitarist made his comeback during a three-song set at a benefit show, The Tibetan Freedom Concert, in June 1998.

A little over a year later, they released the stellar Californication, an album that added depth and maturity of age to their music and still stands as one of the great Californian rock records. More remarkably, Californication didn’t just restore the Chili Peppers’ fortunes, it also made them even bigger than they’d been before.

“We’d had a lesson of being drastically humbled,” Kiedis says of the rocky mid-90s, “and with Californication we weren’t coming at it from an arrogant place or a successful place. John had nothing, he’d burnt through everything. We were starting overfrom scratch.”

The momentum carried on through 2002’s sparklingly melodic By The Way. Their next album Stadium Arcadium was tougher to make and tougher to sell: a sprawling, 28-song double album whose songs veered fromWest Coast psychedelia to Krautrock-inspired pop, and acted as a showcase for Frusciante’s inventive guitar playing. Both of those records sold in the millions, and the tours became bigger and more successful. And then, in 2009, Frusciante announced that he was quitting the Chili Peppers again.

When I ask Frusciante why he left for the second time, he hesitates before replying. His answer, when it comes, is honest yet diplomatic. But then overnight I get an email asking if he can clarify a few points.

His follow-up answer is long and detailed yet clear-headed and, if anything, even more revealing than his original response. In it, he talks about how he “became quite off-balance mentally those last couple of years we toured”, partly a result, he explains, of the effort of mixing Stadium Arcadium. “When I went on tour, we had just finished mastering the day before, and I could really have used a breather.”

At another point he writes about evenly is his interest in the occult. “As the tour went on, I got deep into the occult, which became a way of escaping the mind-set of tour life. The occult tends to magnify whatever you are, and I was an imbalanced mess.”

When the tour finished, he says, he realised he needed to “simplify my relationship to life and music. My ego had become too big a part of what I expressed as a guitar player.” Instead he began to immerse himself in making and playing electronic music, to “start afresh”. The impression is of a man who was feeling the pressure of responsibility – to his bandmates, to the fans, but mostly to himself.

“Of course, there were interpersonal problems within the group,” he concludes, “but those could have been worked out easily, if not for the fact that I was completely burned out and imbalanced.”

The rest of the band weren’t surprised when he informed them that he wanted to leave.

“John was very absolute about not wanting to do this any more,” says Kiedis. “So when he told Flea and I, there wasn’t even that moment where we were like: ‘Come on, we can work it out.’ We were like: ‘We understand, it’s obvious it’s not where you want to be.’ I would say ‘relief’ was probably the most descriptive word for everybody, including John.”

Unlike the uphill struggle they faced to fill Frusciante’s boots first time around, the Chilis had a ready-made replacement in Josh Klinghoffer. Almost two decades younger than the rest of the band, he had worked as Frusciante’s guitar tech and played as a backing musician on Stadium Arcadium, as well as appearing on several solo albums Frusciante released during his second stint in the band.

The two albums the Chili Peppers made with Klinghoffer – I’m With You and The Getaway – kept up their creative hot streak. But when they began working on material for their eleventh album, something felt wrong. The pieces weren’t fitting like they should. That’s when Flea told Kiedis that he’d spoken to Frusciante, and that he thought the guitarist might be ready to become a Red Hot Chili Pepper once more.

"I have to tell you something that’s been on my mind. It’s about John…”

The conversation between Flea and Kiedis that took place towards the end of 2019 was the turning point that would bring the Chilis to the place they’re in today.

“It was just this bizarre moment in time where John, who had been very divorced from the Red Hot Chili Peppers for so long, off in his own world somewhere, was having the same thought as Flea and I were having, at the same time,” says Kiedis.

It wasn’t a complete no-brainer – there was a range of complex emotions involved, and plenty of historical baggage to process. Frusciante had spent the past decade making electronic music.

“All I wanted to do was make music on machines where I could do the whole thing by myself without having arguments with somebody,” he says. He still practised guitar, he says, but he hadn’t written an actual rock song in years, and wondered if he could still do it (it turns out he could: the first song he came up with was the Unlimited Love album’s hazily powerful first single Black Summer).

There was also the matter of Klinghoffer. Flea invited him to his house for a band meeting, where he was told that Frusciante was coming back.

“I crashed my car into the garage, I was so freaked out about it,” Flea says of the meeting. “Look, Josh is an amazing person. He was helpful for me personally, as someone I could go to when I was hurting and crying on the road. He played great, he contributed, he’s an awesome person. But we had a language with John that we developed when we were all much younger.”

Klinghoffer subsequently revealed that his firing felt “like a death”, although there appears to be no lasting bad blood. Kiedis has spoken to him since his departure, and Klinghoffer plays alongside Chad Smith in Eddie Vedder’s solo band. He also plays with Pearl Jam (“A band he loved more than anything,” according to Kiedis) as a touring guitarist.

Yet ultimately it was a no-brainer, and things moved fast. Frusciante took a couple of weeks to think about whether he really wanted to do this, decided he did, and there he was (albeit with some conditions, which he won’t divulge). He suggested that they get reacquainted musically by jamming old Chili Peppers songs that predated his and Chad Smith’s arrival in the band. They also covered a bunch of old blues numbers by Freddie King and John Mayall, and classic songs by The Kinks, the Beach Boys, even the Bee Gees.

“I didn’t think it would be very good after not playing together for ten years to go straight into writing cold,” Frusciante says now.

The pandemic proved fortuitous, allowing the band more time and privacy than normal to work on Unlimited Love with producer Rick Rubin, who was himself returning to Team RHCP after sitting out The Getaway.

Like all their best albums, the result is recognisable as a Chili Peppers record without sounding like any record the Chili Peppers have made before. Even – especially – the ones they’ve made with Frusciante.

“John Frusciante is the best musician I’ve ever played with,” says Flea. “It’s in everything from the little details to the big picture. His relationship to music is so pure and has so much integrity and knowledge and work and practice. Every note he plays is born of this immense heart. It’s so beautiful.”

Do you tell him that? “Fuck no,” Flea snorts.

“I don’t tell him that.”

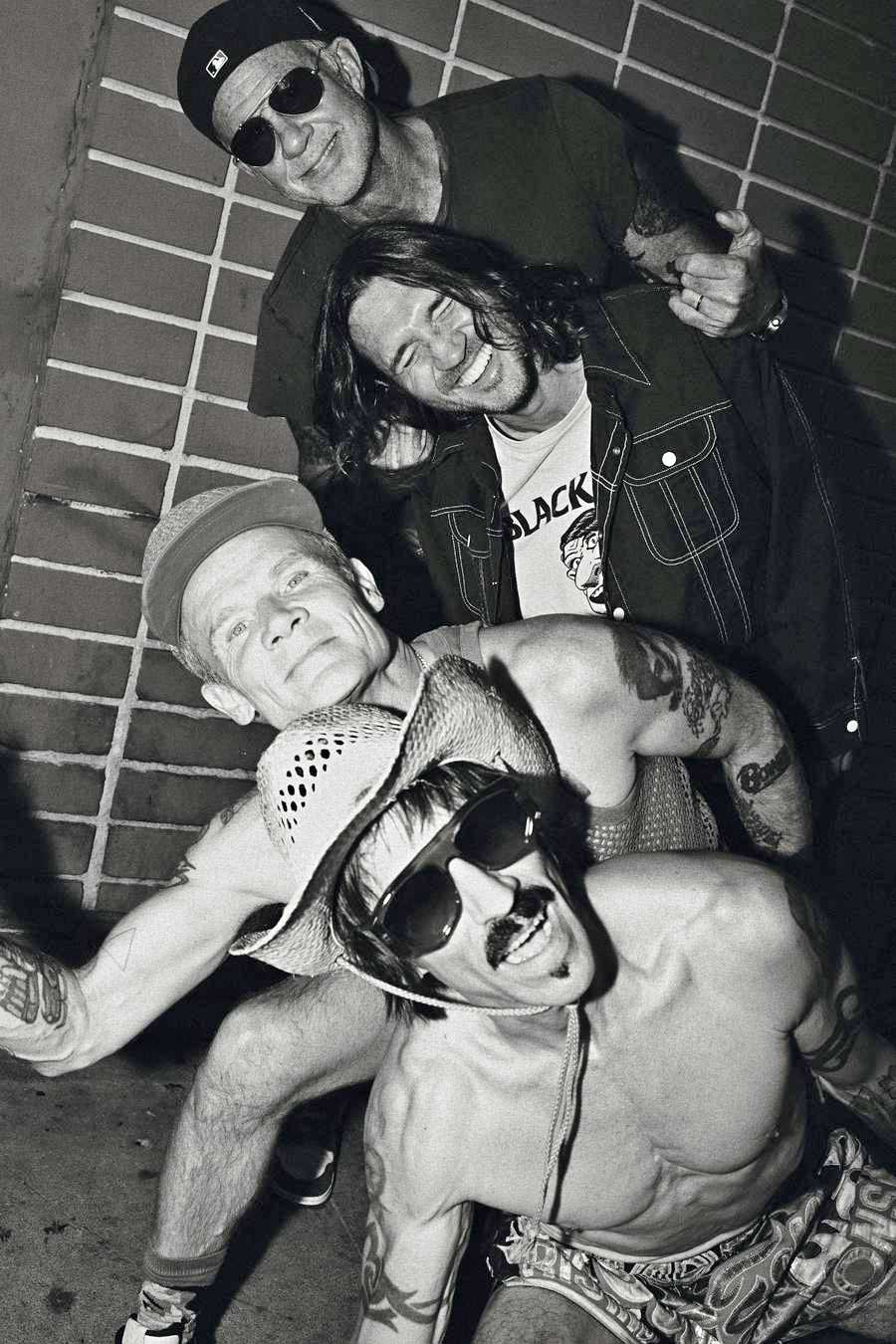

And so here we are again. The perpetually complex system that is the Red Hot Chili Peppers is in motion once again. As in 1999, it feels complete once more. Of course, there’s an elephant in the room. Frusciante has left the band twice before. It feels kind of churlish to bring it up, but it needs asking: are they worried that he might do it a third time?

No, Kiedis says, it’s honestly not something that has crossed his mind. No, says Flea, they’re living in the moment, things are great, why would they consider it? Once again, Frusciante takes his time to answer the question, then later emails an even more thoughtful response.

“There’s no way to see into the future,” he says, before explaining that no one asked for any assurances either time he rejoined. Sure, he adds, if things became “toxic and unhealthy and there is no conceivable way to fix it”, he probably would quit – no one wants to make the others do something they didn’t want. And then he gets to the nub of the relationship not just between the Chilis and John Frusciante, but also between the Chilis and each other.

“The beauty of playing with this band is that we really do love listening to each other,” Frusciante says. “I love hearing the way they make me sound. We have a chemical effect on each other. We bring things out of each other that we can’t bring out of ourselves. The way I play guitar with them is a style I can’t play on my own. The chance to make another record like that has meant everything to me. We’re all just glad this is happening right now. Our hearts are in it, and so it feels right.”

The return of Rick Rubin

“The feeling in the room when Flea, John and Chad play together is transcendent,” Unlimited Love producer Rick Rubin tells Classic Rock of the band he’s worked with, on and off (mostly on), since 1991. “Then when Anthony sings it becomes the Chili Peppers. The musical highs they are capable of channelling on a regular basis is otherworldly, truly a case of the ingredients tapping into something much larger than the sum of its parts. And the parts are as good as it gets.”

John Frusciante isn’t the only person to have returned to the Chili Peppers fold for Unlimited Love. The other is Rubin, who ceded production to Danger Mouse for the Chilis’ previous album, 2016’s The Getaway, largely at the request of then-guitarist Josh Klinghoffer.

“Rick is a family member,” says Anthony Kiedis. “I didn’t know how much I’d miss him until we decided to make a record without him. As an energetic force, a dynamic force and a mysterious force, he was missed.”

Rubin was successful before hooking up with the Chilis, having worked with the likes of Run DMC, Slayer, The Cult and, most notably, the Beastie Boys, whose debut album Licenced To Ill sold more than 10 million copies. But Blood Sugar Sex Magik was a mutually beneficial experience, kicking the Chili Peppers’ career into the stratosphere and establishing Rubin as one of the key sonic gurus of the modern era.

“Nobody can listen like that man can listen,” says Kiedis. “He sat there and just let us play all of this music, and he listened and he smiled and he bopped around. It was: ‘Okay, we are back. We now have the power of Rick Rubin on our team.’”

Unlimited Love is out now.

Dave Everley has been writing about and occasionally humming along to music since the early 90s. During that time, he has been Deputy Editor on Kerrang! and Classic Rock, Associate Editor on Q magazine and staff writer/tea boy on Raw, not necessarily in that order. He has written for Metal Hammer, Louder, Prog, the Observer, Select, Mojo, the Evening Standard and the totally legendary Ultrakill. He is still waiting for Billy Gibbons to send him a bottle of hot sauce he was promised several years ago.