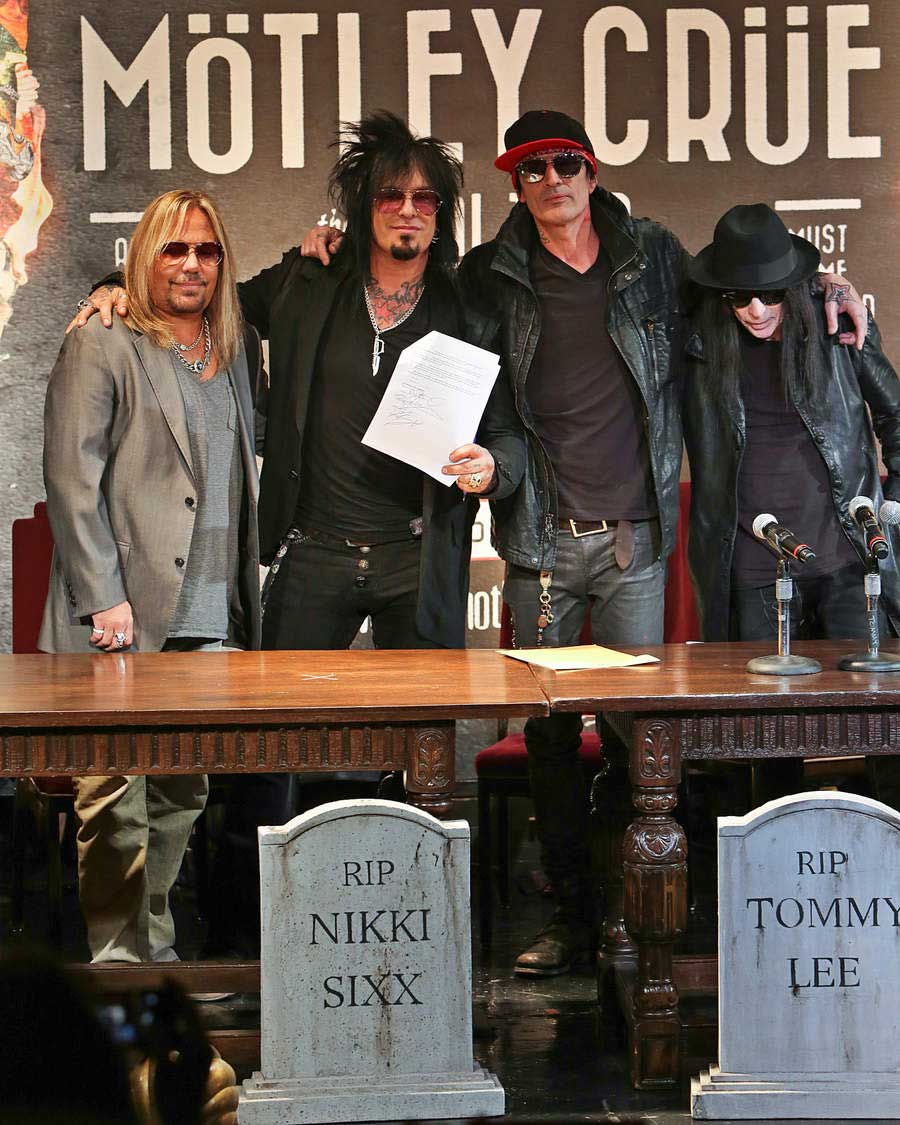

The Nikki Sixx interview: rebellion, danger, and what makes Vince Neil excel

Nikki Sixx: the problem child who became the ringmaster of LA’s Sunset Strip, wrote the anthems that built hair metal and set the gold standard for excess

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

A pop psychologist would have a field day with Nikki Sixx. He arrived on the California birth register on December 11, 1958 as Frank Carlton Serafino Feranna Jr. A smart, sensitive kid, he was soon to be deserted by his Italian father and dragged across the States on the whims of his untamed mother.

Next, he was a troubled teenager with a burgeoning rap sheet, which featured theft, slashed tyres and schoolyard drug deals (50 cents for two joints). But it was Feranna’s touchdown on the Sunset Strip in Los Angeles in 1975 – and his rebirth as Nikki Sixx – that proved the defining moment of his life, as documented in his new memoir, The First 21.

Patently a star-in-waiting, Sixx got his golden ticket as chief songwriter and bassist of Motley Crue – an aptly named rabble who ran through the 80s like wild dogs, occasionally looking up from the strippers and cocaine to toss us the era’s most glorious stadium anthems.

Article continues belowFrom Shout At The Devil to Dr. Feelgood – not to mention underrated side-project Sixx:A.M., whose new Hits package accompanies the book – Sixx’s 100-million-selling catalogue should not be brushed aside. But no interview is complete without an excavation of the man’s considerable infamy, and though we’ve been warned by his management not to ask about his wild years, Sixx himself is happy to bend that proviso.

“Life happens,” he shrugs, “and suddenly you’re eating Cap’n Crunch with Jack Daniel’s in the morning, and snorting and drinking and car-crashing…”

You write powerfully about your childhood in The First 21, and especially the absence of your father. How do you feel about him now?

In my earlier book, The Heroin Diaries, there was a lot of disclosure about how I felt about my family. I had preconceived notions of what had happened to me – mixed with drugs – so I was pretty angry and confused and couldn’t get a lot of answers.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

With this book, I went back and reached as many people as I could from my life and it ironed out some of the wrinkles. For years, it was like my dad had bolted for no reason. Because that’s the story that I was told, mostly from my mom. It was like, “Yeah, your dad was an SOB, he just left us here.” But following the footsteps backwards, talking to a lot of family members and the people who were there, all the way back to my birth – we don’t know if that’s necessarily true.

My mom… she was difficult, let’s say, and extremely charismatic and hard-headed. Maybe I got some of those characteristics from her. But there are question marks. Maybe my dad didn’t leave, maybe he was forced out. How am I different from my dad? I’m different in that I have been in my children’s life since they were born, and he wasn’t. And for what reason, we don’t know.

What was it about rock’n’roll that spoke to you?

I remember hearing someone say, “That heavy metal is going to turn you into a degenerate!” And I thought, “That sounds like a pretty good path, I think I’ll take that one.” Like, “You can have Donny and Marie, or you can have Aerosmith and the Sex Pistols.” Hmmm, let me think about this…

You started kicking out at authority as you grew up. Why was that?

I think I learnt to survive. And you’ll read in the book about a lot of the things I did that I’m not proud of. But I was a young kid. Selling pot was a way to buy musical equipment. I was dead-ass broke, and if I wanted a guitar cable, between pawning stuff, giving blood, sometimes stealing, whatever I had to do, it was all for the better purpose of “I want to be in a rock’n’roll band.”

Is it rebellious? Is it anti-authority? Or is it just, I gotta do what I gotta do? I didn’t have anybody I could ask for money. I wasn’t born with a silver spoon in my mouth. I didn’t really have a place to live. But something about the way my brain is wired is, if I have a goal, nothing will stop me. It doesn’t mean that it’s always the best path to success. As I’ve gotten older, I’ve changed how I handle things. But it’s always been very important to me to be successful.

What are your memories of being bullied at school?

We were living out in the middle of nowhere, in Anthony, New Mexico. And kids are kids. They can be cruel. I’m a father of five. I’ve seen it. It’s how humans are wired. When I finally fought back, I think two things happened. One is that I took control of the situation. No longer were people going to do that to me. The other was that I was willing to face the consequences.

So when my grandfather picked me up and took me into the car, I thought I was dead meat, right? You can’t strike out, beat the shit out of other kids at school, because they’re just gonna go, “You’re the bad guy.” Not them. They’re the ones with the bloody nose, not you. But my grandfather, I remember he told me: “I’m proud of you for standing up for yourself.” That had a big effect for me. Standing up for myself. Standing up for what I believed in. You can go deeper. It was an important moment.

The book is subtitled How I Became Nikki Sixx. Do you see Nikki as a character, an alter ego? What is he?

No, Nikki Sixx is a breathing, living man. And Frank Feranna was a young boy. The two had a collision course in the late seventies. I really didn’t use my birth name, because of the information that was handed down to me from my mom. As a pissed-off-at-the-situation kid, I wasn’t going to take the name of my dad, who abandoned me. I think, at the moment that I legally changed my name to Nikki Sixx, I left Frank Feranna behind. But through a lot of years and having children and learning more about my own dad, it’s been a bit of a full circle.

My twenty-year-old daughter, her name is Frankie. I have another daughter called Ruby, but her middle name is Feranna. For the book, I went back and talked to all my childhood friends, ex-bandmates, I even found my first girlfriend, which was mind-blowing. We got to reminisce. And it really did remind me that Frank was a dreamer – and Nikki Sixx was his assassin.

Tell us about your arrival in Los Angeles in the mid-seventies.

I came to LA at seventeen, on a Greyhound bus, and I went for it with complete, utter, insane focus. Here I am, all the way out in California. I’m young and I’m on my own. But those early bands – with Lizzie [Grey] in London and even when we were playing with Blackie Lawless in Sister – that was like magic. Because it was everything that I had heard in my head when I was falling in love with rock’n’roll on the AM/FM radio.

And those bands really were family to me. That’s why it’s very painful for me when I’m in a band and all the pieces don’t fall together. Because it’s my brothers. When you ventured onto the Sunset Strip, you were always getting in fights, particularly at the Starwood club.

Why did people find you so provocative?

I mean, I don’t think it helped how I dressed. Y’know, all the punks would go to the punk night there, right? And then you’ve got some crazy, glam, Johnny Thunders, Stiv Bators-looking “girl” – y’know, they’re gonna say shit. And that’s why I went there. I went there for that very reason. I don’t want to fit in. I just don’t want to. I’ve never understood the concept of fitting in.

I think that’s why Motley Crue always changed our logo, changed our image, changed our sound, on every single album. And it’s why, when Mötley Crüe would play in the early days and people would flip us off and they didn’t get it – we loved it. We felt like we must have been doing the right thing. I still feel like an underdog – and I like it.

Who was the best musician in Motley Crue?

They’re all really fucking good. Tommy [Lee] is a monster on drums. Mick [Mars] is one of my favourite guitar players. And Vince [Neil] has something that nobody else has. Isn’t that what you’re looking for – guys that don’t sound like anybody else? I’m not a great player. Like, if I really woodshed for six months, I’m okay. But if I was a different kind of bass player, it would offset the sound of the band. Motley Crue is an interesting band, because if you remove any one member, it completely changes the sound.

We all played against each other. A lot of times, Vince would tell me he struggled with the fact I put so many lyrics in a song. Shout At The Devil is a good example. But it was because I grew up with beat generation writers as a teenager, and I would get into this kind of rhythmic frenzy. And because of the way that Vince sang, that was what made his voice excel. His voice was kind of like a Gatling gun. Like, bap-bap-bap. I remember the first time the four of us ever played together, we ran Live Wire. I turned around to adjust my bass amp, and Tommy and I just gave each other a look: “Something’s happening here.”

What did you want Mötley Crüe to be when you first started out?

We didn’t want to be like anybody else. And we didn’t care if you liked us. We all emulate, of course. That’s human nature. You take a little of this, a little of that. But you’re also doing your own thing and going by your gut. We loved the angst of punk.

Whether it’s the Buzzcocks or Sex Pistols or Ramones – the list goes on – it’s just fucking great songwriting. Raw. Simple. You line that up against Black Sabbath and those big, simple riffs. And then all of a sudden you throw in some Cheap Trick on top of that – it gets really fun, y’know?

What was the most outrageous stunt you ever pulled to get attention at those early club shows?

The answer is – we weren’t doing it to get attention. We were doing it because we were just fucking nutters. We just wanted to keep topping ourselves. It wasn’t like Vince said, “Hey Nikki, I’m gonna light you on fire and then we’ll get attention.” It was more like, “Hey, let’s light Nikki on fire and then chainsaw the head off a fucking mannequin.” “Alright!”

It was just, like, what more could we do to entertain ourselves? In a lot of ways, I think that Live Wire video is a great example of that. We were like, “We’re gonna make a video. We don’t know if we’ll ever make another one in our lives. So let’s throw everything and the kitchen sink at it.” In the end, though, Mötley Crüe found an audience.

What do you remember about the moment when you started to break through?

We kinda got everybody enjoying the band. I remember that Dead Kennedys and Fear fans would be at our shows. I think it was this combination we had of punk-rock glam with power-pop, played like heavy metal. People were dying for rock music. But the gatekeepers didn’t get it. Nobody wanted to sign Motley Crue. Nobody had wanted to sign my band London, either – and we were the biggest band in Los Angeles at the time.

The record companies didn’t get it, because they wanted what was coming: A Flock Of Seagulls, The Knack, The Plimsouls, The Go-Go’s. Which was fine – but we were not that. So there was no chance for us to get on a major label. But you don’t need to worry about any of that stuff. You don’t need to worry about the press. You don’t need to think about some twenty-two-year-old A&R guy who is just worried about the record company president and whether he’s gonna get fired if he makes a mistake.

You just have to say, “I’ve got nothing to lose and I’m gonna go for it.” And history is written mostly by those people. So Motley Crue started our own record company. After that initial record sold [1981’s Too Fast For Love], and everywhere we were playing was selling out, somebody at a record company went, “Y’know, we might be able to make some money off these boys.” And they did.

What do you think was the song that pushed you into contention?

Y’know, I remember somebody telling me that a radio station in Phoenix had played Live Wire, and their phones had lit up like they hadn’t seen in years. There was another station in Arizona, and they played the song: same thing happened. We started watching this thing happen with that song, which is so raw, and the lyrics are so in your face. We started seeing the same reaction in other cities, that we were already seeing in LA. It was an exciting time. Every band can remember their first time like that.

When you reflect on Mötley Crüe’s most imperious years in the eighties, do you think you were a sexist band?

In today’s environment, most probably. As was everybody. In the seventies, when I grew up, it was just the messaging that came through, and you were emulating your heroes. I remember the line from the first Aerosmith album. He goes: “Heading out to New York Slitty.” [Sixx presumably means the ‘slitty licker’ reference in Pandora’s Box.]

And I was like, “Wow. That’s fucking rad.” It was dangerous, y’know? When someone’s talking about guns and sex and drugs, you’re like, “This is fucking dangerous, man. This is not mom and dad’s music.” So it was a different time. You can’t rewrite history, man. You can’t rewrite the sixties. You can’t rewrite the fifties. We can try… but why?

Does it bother you when people still think of Motley Crue as hellraisers first and musicians second?

Well, I guess that depends on who you talk to. It was obviously great for the media to have something to write about. I remember that Elektra Records’ publicist, Bryn Bridenthal, was so bored of the bands we talked about earlier. Y’know, here comes another band with the hand-claps in the background. She walked into her office – this was the first time we’d been to New York – and I was in all-black leather, peeing in a plant.

The other guys had their boots up on her desk and were drinking a beer, and it was, like, ten in the morning. So Bryn walks in, she looks at everybody and she knew we were the new band on the label and she goes: “I think I just fell back in love with rock’n’roll.” She knew, this band are just on their own planet. They’re on their own mission. They’re writing smashing songs. They look fucking cool. They keep adjusting. Whatever’s going on, they move out of that lane.

Do you think you encouraged that infamy?

They had a thing at Elektra Records at the time, a kind of newsletter. And it would always be: “Motley Crue throws television out of window,” or “Tommy drove a golf cart into the swimming pool at the hotel.” And it would go to radio, and it would go to media. And because it was the eighties, it was fun.

Because it was the eighties, it was like, “Wow, this is exciting, I can’t wait to go see them.” Because it was the eighties, when you finished dinner, someone would pull out some cocaine and pass it around, and no one cared. Because it was the eighties, everybody was just fucking having a great time. So, in retrospect, what Bryn was magnifying was just us being us. And being young and not really thinking about repercussions, and not thinking about long-term careers.

And then it becomes The Dirt. It becomes Hammer Of The Gods. And people think of you in conjunction with your music and the antics. I don’t believe they’re separate. I think that fans listen to our music and think, “That was a fucking great time. That was a wild rock’n’roll band. That was a lot of fun.” I don’t think of the Rolling Stones’ antics and their music as separate. I think they go together.

1989’s Dr. Feelgood was the band’s biggest seller – but do you think it’s your best album?

I think there’s some shining moments. I think all of our albums have really shining moments. Every album has the songs like Kickstart My Heart, Shout At The Devil, Live Wire or Wild Side. They all have ’em. But they’re albums. Even with my favourite bands, it’s more about the whole package. I listen to whole records. I don’t listen to singles.

Kickstart My Heart is a really interesting song, though. I remember, it was hammered out on acoustic guitar. It was a bit more of a punk-rock idea. The lyric, I was being a bit snarky, because radio and MTV was starting to get more nervous and corporate. So the opening line was: ‘When I get high, I get high on speed’. But then, the next line was: ‘Top fuel funny car’s a drug for me’. So it was like, I got out of it, y’know? Like, just close enough but not too close to the flame.

In December 1984, Vince was behind the wheel for the car crash that killed Hanoi Rocks’ drummer, Razzle. How did that incident change the atmosphere in the band?

I think it was the worst-case scenario for everybody involved. We’ve talked about it a lot. It’s just something that Vince… we can’t take it back, y’know? And we can’t really say anything more now, because there’s families involved.

Are you better friends with Vince, Mick and Tommy now than when you first started the band?

Well, we know each other so well. Do you know anybody you’ve been through as many highs and lows with as Mötley Crüe has for forty years? I don’t. I know all their strengths and weaknesses, and we try to be there for each other. But at the same time… somebody asked me the other day, “Do you guys all ride together on the same bus? Do you have the same dressing room?” And I thought, “Well, how sweet.” I don’t live with the band.

Does it feel unreal now when you think about the highs you reached with Motley Crue?

You totally forget. Y’know, we live near a town of 9,000 people now and I’ll just be walking down the street and someone will come up and they’re like, “Oh man, I love your band.” And it snaps me back into thinking: “Oh, right.” Because I’m living in the moment. I’ve never been one to have gold or platinum records in my house. I did it a couple of times, but I didn’t want people to come to my house and go, “Whoa, look what you’ve done.” I want people to like me for me.

So I kinda forget about it sometimes. And then, when I get reminded, I’m so grateful that I got to do this with Tommy, Vince and Mick. It’s like, Motley Crue, we sold a lot of fucking records. We sold out the world multiple times. It was amazing. What we wanted, we got. It was a hard-working, blue-collar, put your head down to the grindstone and work your ass off band, since the beginning. But we are not stupid enough to believe that we are the almighty. We also – like almost everybody else – got lucky.

Do you ever think it’s unfair that so many clean-living people die young, while you’re still fit and healthy at sixty-two?

Y’know, I think this falls a little bit under the question you had earlier about lifestyle. A lot of people don’t realise this, but I’m 20 years sober. But before that, I had six years of sobriety. And before that, I had four years where I was clean, right? For those first [periods of sobriety], I went up and down.

But I’m really looking at somewhere between twenty-five to thirty years of not sticking needles in and drinking alcohol and taking pills and stuff. I actually live a pretty clean lifestyle. But people don’t think that when I walk into the restaurant. People are always like, “Hey man! What’s happening? High five! Let me buy you a shot of Jack Daniel’s!” I’m like, “It’s been three decades!”

What have been the high points of recent years?

Two things have really changed my life over the last few years. Firstly, there was The Dirt movie in 2019. Y’know, 73 million people or whatever it is now have seen that movie, and it’s made an impact on not only our fans but people who had heard of us, had maybe heard a song or two. Younger people, they don’t really see rock bands like that. The new rock bands… [laughs] well, it’s a different time. Probably rightfully so.

So the birth of the movie and also The Stadium Tour. We didn’t think we would ever tour again, via our own decision. But when the offer came for stadiums and Def Leppard, it was like, “Well, you know what? I guess rules are meant to be broken, because this is going to be one hell of a celebration.”

In the new book, you write about pounding the treadmill and hiring a nutritionist in preparation for The Stadium Tour. Some Crüe fans might find that strange to hear…

Yeah, I think it might surprise some people. The reason I put it in the book was I wanted people to understand what the process is like if you want to compete. I’m looking at going onstage with Def Leppard, and those guys are fucking great, every single time. Poison, they bring it. Bret [Michaels] really focuses on his performance. And Joan Jett has always been an ace. I also look at Metallica, and I’m looking over at Aerosmith, and I’m thinking, “What’s Slipknot doing?”

I keep my eye on what’s going on out there, and I do not want to be the guy who’s onstage and they go, “Well, old Nikki Sixx, it doesn’t seem like he’s got the steam anymore, y’know?” Fuck that! So I’m gonna work harder than anybody else, because that isn’t gonna be my story. So that’s why I wanted to show that. Whether it’s rock’n’roll or not, I don’t know. I don’t even know what rock’n’roll is anymore. I think it’s just doing whatever the fuck you want to do.

You’ve had to reschedule the tour, of course. How frustrating was that?

Not all the fans a hundred per cent understand. They’re like, “Why are you guys not touring?” Well, it’s because we care about you. We don’t want to be the story where it’s like, “People got sick during The Stadium Tour and some of them passed away.” I don’t want that for rock’n’roll.

It feels like Mötley Crüe have said goodbye to us a few times now. Will this thing ever actually be over?

Well, eventually, one of us is going to die. I don’t know, man. I tell you what – since the pandemic, I am just living day by day. And shit happens.

The First 21 is out now via Hachette Books. Sixx:A.M.'s Hits collection is also out now.

Henry Yates has been a freelance journalist since 2002 and written about music for titles including The Guardian, The Telegraph, NME, Classic Rock, Guitarist, Total Guitar and Metal Hammer. He is the author of Walter Trout's official biography, Rescued From Reality, a music pundit on Times Radio and BBC TV, and an interviewer who has spoken to Brian May, Jimmy Page, Ozzy Osbourne, Ronnie Wood, Dave Grohl, Marilyn Manson, Kiefer Sutherland and many more.