How Blood Sugar Sex Magik almost killed the Red Hot Chili Peppers

When the Red Hot Chili Peppers released Blood Sugar Sex Magik in 1991 it was a blessing and a curse, propelling them to stardom while taking them to the brink of oblivion

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

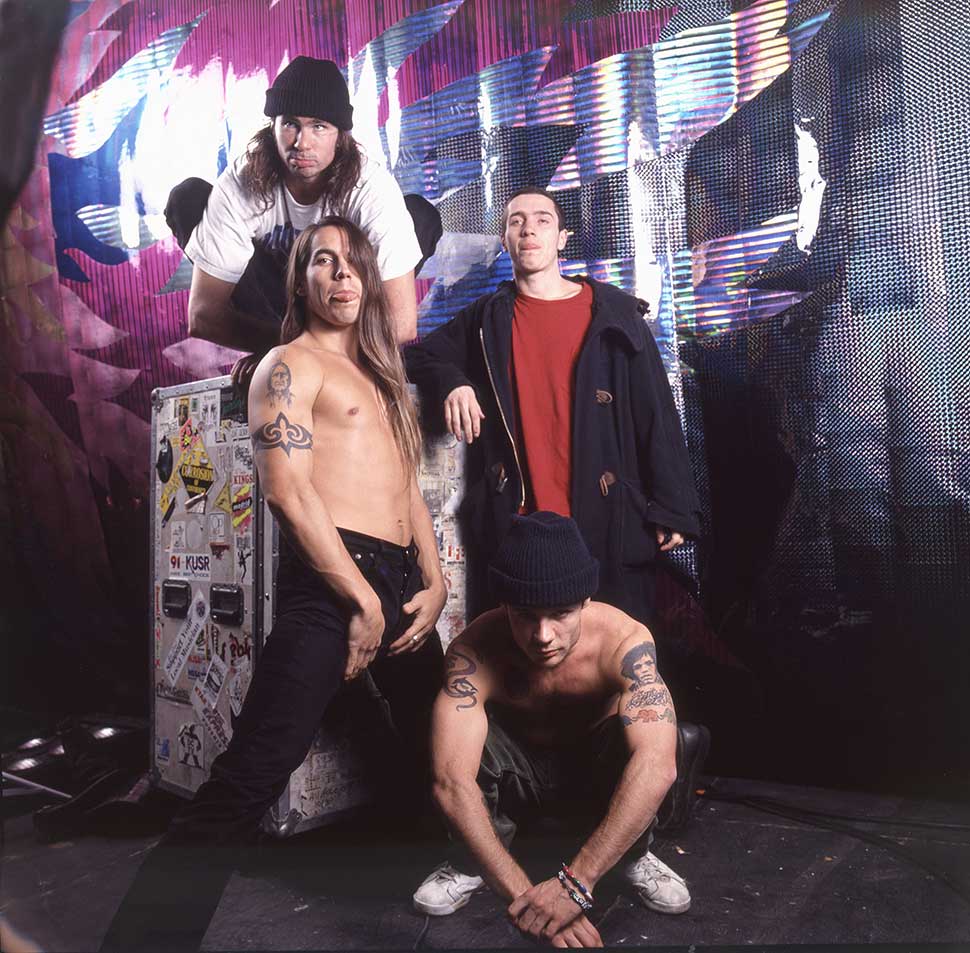

At first, Red Hot Chili Peppers frontman Anthony Kiedis didn’t know if he wanted his band to work with infamous producer Rick Rubin on the album that would become 1991’s Blood Sugar Sex Magik. Somehow he felt that the chemistry might not be right.

“We didn’t know if he would be able to blend in well, what with Slayer and the boiling goat heads of Danzig and all,” Kiedis admitted later, referring to Rubin’s previous work. “But he turned out to be a completely open-minded, free-flowing, comforting spirit. If Baron Von Munchausen were able to ejaculate the Red Hot Chili Peppers onto a chess board, Rick Rubin would be the perfect player for that game.”

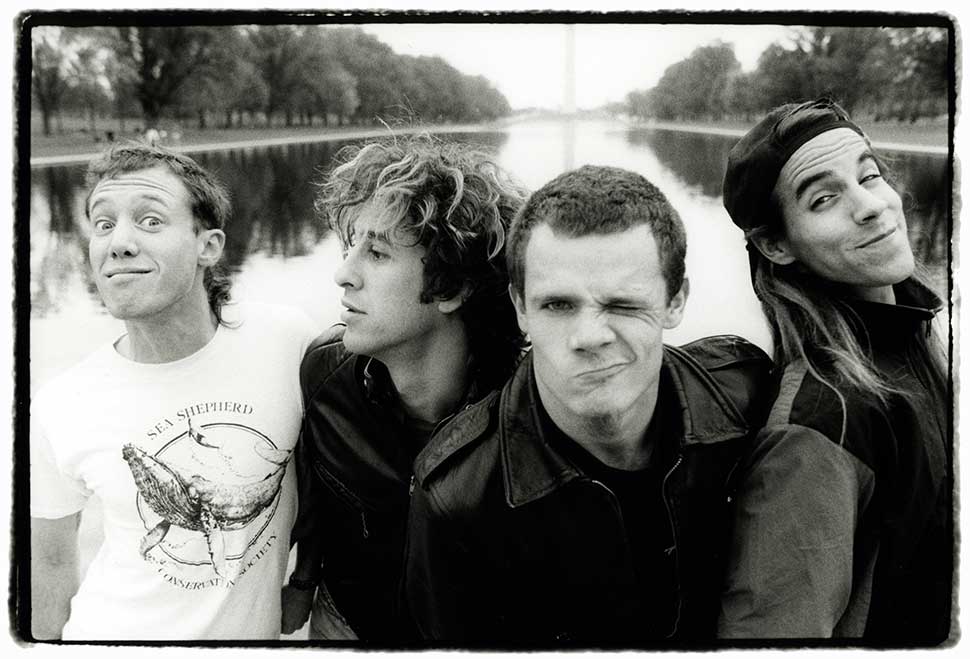

Kiedis’s reservations were understandable. The tail end of the 80s had hit the band hard, but had resulted in an upturn in their commercial fortunes. But that had been tempered by the death of founding member guitarist Hillel Slovak, from a heroin overdose. Slovak had almost been pushed out of the band early in 1988, as his health and playing were beginning to visibly deteriorate, and after a ramshackle Chilis show in Washington the band had decided to jettison the troubled guitarist.

That decision was averted at the last minute when Angelo Moore, of the Chilis’ support band Fishbone, heard of the plan and talked Kiedis out of it, reasoning that Slovak needed his friends now more than ever. Kiedis relented, and Slovak travelled with the band to the UK – he rarely appeared for any of the interviews they did here; he was usually said to be ‘sleeping’. Four weeks after their return home, in June 1988, he was dead.

Naturally, Slovak’s death threw the band into disarray. Drummer Jack Irons quit the band (he would later join Pearl Jam), blaming the others for his friend’s death. Kiedis went into self-imposed exile in a small Mexican village in an attempt to clean himself up, with the knowledge that at one point in their recent history it had been hit or miss whether it would be he or Slovak who would check out first.

“I fucked up so bad in my mid- and early 20s on drugs. I had no choice but to change if I wanted to stay a productive, creative, happy and alive human being,” Kiedis recalls.

By the time Kiedis had returned to Los Angeles from Mexico, bassist Michael ‘Flea’ Balzary’s then wife Loesha had given birth to their daughter, Clara (her name is tattooed above his heart). Giddy with delight but also still stricken with grief, Flea and Kiedis set about rebuilding the band.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

In the interim, they accompanied a painfully shy 17-year-old guitarist named John Frusciante – a regular at their club shows in LA – to a audition for a local group called Thelonious Monster. It was while sitting through his audition that Flea and Kiedis were first struck by the young guitarist’s natural flair and his ability to mimic Slovak’s style. They quickly decided to poach him for the Chili Peppers.

Unfortunately, the ensuing tour suffered from the band’s high-profile antics, with two disparate events linked together in the media’s glare, temporarily branding the band as sexist and hedonistic and finding them charged with and guilty of criminal behaviour. First, Kiedis was convicted of ‘indecent exposure and sexual battery’ following an incident after a concert at George Mason University in Virginia, where – as a prank – he dropped his pants in front of a female concertgoer.

The following year, during the taping of an MTV Spring Break special in Florida, Flea and Chad Smith jumped off stage, Flea grabbing a woman and carrying her on his shoulders while Smith spanked her. The two were charged, Flea was found guilty of ‘battery, disorderly conduct and solicitation to commit an unnatural and lascivious act’; Smith was found guilty of ‘battery’.

“It would have been a disaster and a shame to have given this piece of music, of which we’re incredibly proud, to a record label like EMI,” Kiedis said at the time of the release of BloodSugarSexMagik in 1991, adding: “You look at Mo Ostin [Warner Brothers] as someone who signed Jimi Hendrix to Reprise, and then you look at Sal Lacotta from EMI who signed Roxette. You know there’s a slight difference in artistic integrity going on there.”

Surprisingly in the light of that statement, the Chili Peppers linked up with Warner Brothers, having chosen to go with CBS but then opting out of that deal at the last minute.

“We decided to go with CBS – which was pretty much a monetary decision – and at the last minute Mo Ostin called us up to congratulate us on the deal we’d made with CBS. At that point we hadn’t signed anything, but we’d had our photos taken with everyone at the label. But that call kind of revived us,” Kiedis recalls with a grin. “This guy from the label who didn’t get us, then congratulating us anyway. So we thought what a cool guy, stripped down to our skivvies and went swimming in his pool.”

Even though Kiedis had expressed reservations about working with Rubin, the band had actually approached the producer with the idea of working on an album together back when they still had Hillel Slovak playing with them.

“They were really in bad shape drug-wise,” Rubin later told Rolling Stone magazine. “I walked into the room thinking, ‘This is bad.’ I didn’t want to do it. Then when I met them for Blood Sugar… they were like a different band, completely in control, ready to do something good.”

Famously, Rubin found a mansion, built in 1917, out on Laurel Canyon Boulevard as the place to record the sessions that would make up Blood Sugar Sex Magik. Drenched in history, the mansion had played host to gangsters; Hendrix stayed there briefly; The Beatles hung out and partied there, and it’s even rumoured that they dropped their first acid together there.

The Chilis adored their surroundings at the mansion (although Smith refused to sleep there, preferring the 20-minute ride in on his Harley every morning). They spent some seven weeks there in almost total exile, discouraging interruptions from outsiders, and all the while taking comfort from the host of friendly spirits that they said haunted their temporary home and its wildly overgrown grounds.

There’s a deep-red photo on the inner sleeve of the album in which a translucent dis floats innocuously by as the band members playfully embrace one another, unaware of its presence. They insist that it’s one of the spirits, briefly caught in a series of exposures shot for the album artwork.

A wide-eyed Frusciante was a little more awed by his experiences with the paranormal during his stay at the house, as the guitarist once told RAW magzine: “I heard a female ghost there, that was the only time I had any sexual experience there. I was sleeping in the hall and I got really turned on by this female ghost who was getting fucked above me, so I jacked off. The rest of the time all my sexual energy went into my playing.”

- The A-Z of Red Hot Chili Peppers

- Why Flea from the Red Hot Chili Peppers threw a bottle at my head

- Red Hot Chili Peppers to welcome NFL's Rams back to LA

- Red Hot Chili Peppers frontman Anthony Kiedis helps save baby's life

The unorthodox surroundings and unconventional approach to recording inspired the band to new creative heights. Rejecting the norms and received wisdoms associated with making an album, they performed parts under the high-domed ceiling of the ballroom, and occasionally jammed and recorded in the bedrooms or set up equipment in hallways or wherever they felt that the vibe might right.

The band had been warned early on that the building was incapable of giving them a good drum sound. They dismissed the idea, and got past the problem by simply trying different rooms and hallways until they got one. They jammed most of the songs live, then let Rubin put the pieces together.

In Funky Monks, the group’s long-form video of the making of the album, it becomes apparent just how much their recording location had freed them up creatively: at one point Flea plays along with Mellowship Slinky In B Major and Apache Rose Peacock on two tiny children’s pianos; seated at the bottom of the main staircase, the band thrashed along on hubcaps and an empty milk churn for the jangling middle-eight of Breaking The Girl. Anything, it seems, went.

The band recorded 25 songs, of which 22 were originals, and 17 made the final cut. One of these was infamous blues legend Robert Johnson’s They’re Red Hot, which was recorded outside at night, with the sound of cars speeding through the valley below as the band jammed the song playing on a Persian rug laid over the long grass. The sessions also yielded the elegant Soul To Squeeze, which, mystifyingly, never made the album but was released as a single in the US in 1993.

The cover illustration by Henky Penky – let’s not forget this is the band who live once used a saxophonist called Tree – drew heavily on the work of eccentric English artists Gilbert & George for inspiration, transforming the band’s entwined tongues into tattooed thorns.

The album itself reflected a more refined and mellow Chili Peppers, both musically and lyrically. I Could Have Lied and Breaking The Girl – with Frusciante’s chiming acoustic guitar – gave way to a less relentless band opening up to new new ways of translating their groove.

They were still capable of bombast and heavy funk, though, with the monstrous Give It Away coming out of a Flea-inspired jam that Kiedis was instantly smitten by. The grotesque caricature featured in Sir Psycho Sexy had them barracked as sexist and irresponsible, but the lyric is so plainly cartoon-like and fantastical that any criticism seems misguided and reactionary.

My Lovely Man was a love letter that Kiedis sent to Hillel: ‘Well I’m cryin’/Now my lovely man/Yes I’m cryin’/Now and no one can/Ever fill the hole you left, my man/I’ll see you later/My lovely man, if I can…’ He recorded his vocals for the song at night n a makeshift booth set up at a window overlooking the wonderfully overrun grounds, with a square of candles lit along the walls at his feet.

But it was with Under The Bridge that the band struck creative and commercial gold. Kiedis took his enduring love of the band’s adopted home city, Los Angeles, personifying it (‘I drive on her streets/’Cause she’s my companion/I walk through her hills/’Cause she knows who I am’) and making it his starting point before reflecting on his downtime there as a heroin addict: at an ultimate low, Kiedis had been so eager to score that he bought drugs from gang members, and had to pretend to be dating his connection’s girlfriend so that they’d sell him heroin. He bluntly retold the story himself in the Funky Monks video some years later.

“I was what you might call a hard-core junkie for many years, and during that point my life was a very sad time… I’ve been clean for three years now, but during that time I reached some ultimately low depths of incomprehensible demoralisation; this incredibly deep sense of loneliness, of emptiness that you’re trying to fill up with whatever it is you can find. In my case it was drugs.

“One day I was driving back from rehearsals, and I got one of those bursts of loneliness and I just felt like I was all by myself. So I started singing to myself on the Hollywood freeway, and the entire song came through my head. When I got home I wrote it down.

“And what I was referring to in the song was a point in my life about five years ago. All I had was this connection named Mario, who was Mexican Mafia, ex-convict. And one particular afternoon, it was very hot in the middle of the summer, and I’d been up for days, and he and I found what we’d been looking for.

"We went to this bridge that was downtown in the middle of Los Angeles in this ghetto; this freeway bridge, and a little passageway you had to go through to get under the bridge, and only certain members of this Mexican gang were allowed to go in there. And we lied just so we could get in there and do what we wanted to do.

“And that’s always stuck in my brain as a low point in my life. When I talk in the song about being taken to the place I love, that’s here. That’s where I am now, the most sacred place, making sounds with my best friends.”

Acclaimed film director Gus Van Sant (who would later cast Flea in My Own Private Idaho and also brought songwriter Elliott Smith to the public’s attention after using his songs for the soundtrack to Good Will Hunting) shot the video for Under The Bridge when it was released as a single, and focused on Kiedis as he moved through the city.

At one point he’s cruising along an LA freeway as the camera captures the streetlights of the city in long, strobing flames of light. His passenger in the car that night was the actor River Phoenix. Phoenix and fellow actor Keanu Reeves (with whom Kiedis appeared in Point Break) were long-time fans of the band. Years later, when Phoenix died outside the doors of the Viper Room club, it transpired that both Frusciante (Phoenix had appeared on his solo album) and Flea had been playing at the venue that night. Flea ended the evening travelling to the hospital in the back of the ambulance with the doomed Phoenix.

But the heartache didn’t end there. On the band’s final day at the house, Frusciante, arms full of clothes and CD cases, remarked that he’d never felt so proud of anything he’d ever done in his life. Flea insisted that as long as the band could keep their love for the music and for one another, then there was no way they could ever fail.

“After we were finished recording… I pretty much knew I wanted to leave. I’d had a really beautiful time recording it and I didn’t want to go out on tour; it seemed like the antithesis of everything I found beautiful about that album. The direction the band was going in was totally against what I was about.”

He stayed until the following summer, but then eventually quit, disenfranchised by the band’s ever-growing popularity. He announced his decision half-an-hour before the band was due on stage at a show in Japan, and less than one month before the band were due to go out and headline the touring Lollapalooza festival.

In 1996 the Los Angeles Times carried a harrowing account of Frusciante’s torrid lifestyle: a stick-thin junkie living on cans of high-calorie gunk normally consumed by the elderly and invalids. He almost died when it was discovered that his body was carrying only a twelfth of the blood it was supposed to contain, and what blood there was was infected, making his system temporarily incapable of creating red blood cells.

Although Kiedis was at the time initially sceptical that the reunion could work, he now freely admits to being delighted by the results of an album that harks back to the glory days of Blood Sugar Sex Magik.

As he told Rolling Stone magazine: “You never get sick for no reason. And things turned out just the way they were supposed to. I don’t think we would have what we have right now if all that messed-up stuff hadn’t happened. We all know not to project how many years this is going to work. Right now, it’s working like crazy.”

This article originally appeared in Classic Rock 18.

Philip Wilding is a novelist, journalist, scriptwriter, biographer and radio producer. As a young journalist he criss-crossed most of the United States with bands like Motley Crue, Kiss and Poison (think the Almost Famous movie but with more hairspray). More latterly, he’s sat down to chat with bands like the slightly more erudite Manic Street Preachers, Afghan Whigs, Rush and Marillion.