Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

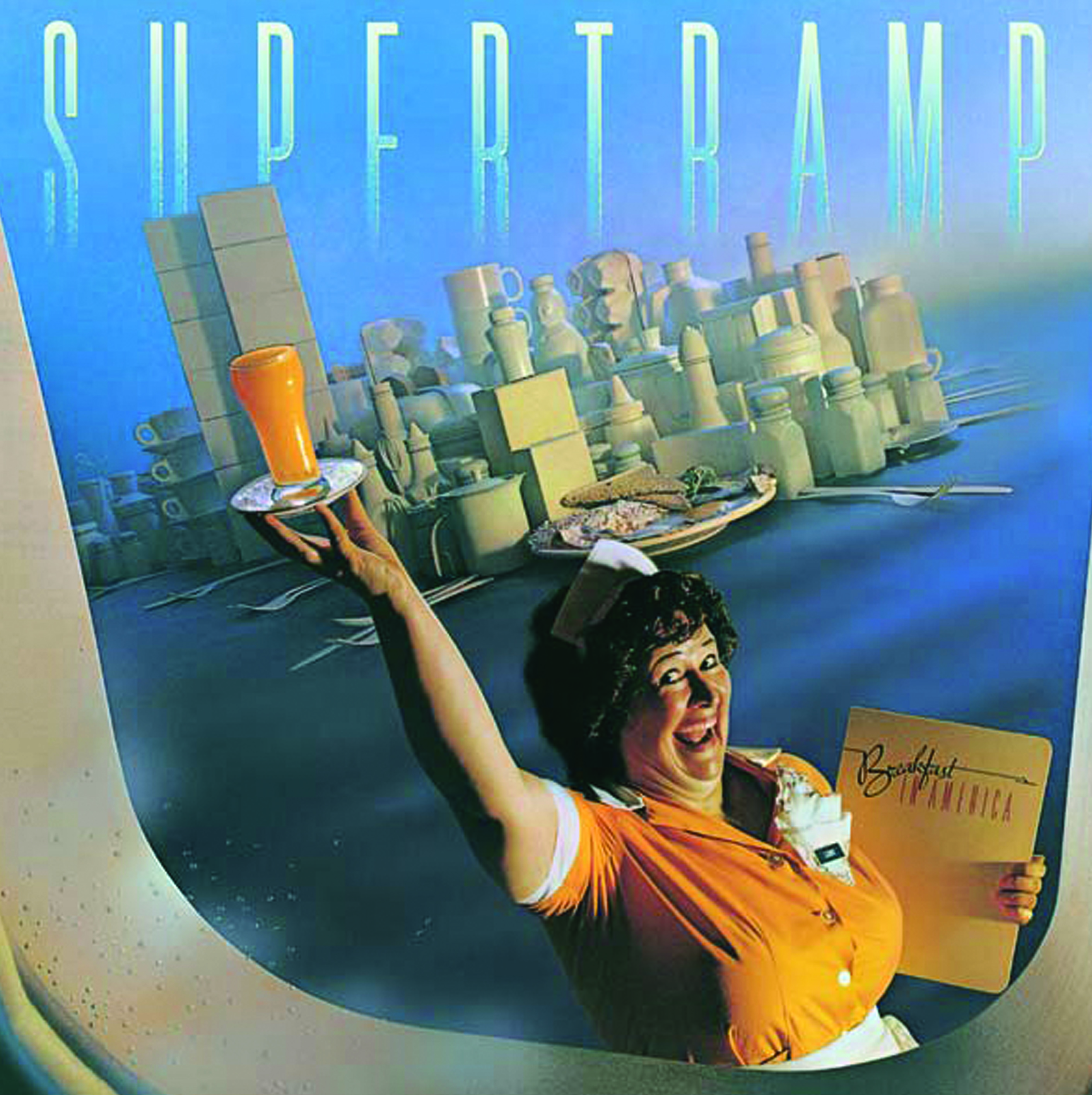

With anywhere between 18 and 20 million copies sold worldwide, Breakfast In America is arguably the biggest-selling prog album of all time after Dark Side Of The Moon.

Not that it was very prog – the sleeve featured a waitress pretending to be the Statue Of Liberty against a backdrop of crockery pretending to be the New York skyline; it was released well after prog’s original golden age; and it wasn’t what might be regarded as a quintessentially prog package: it only comprised a single disc and contained 10 tracks – lengthy tripartite song suites were notable by their absence.

The total running time was a meagre 46 minutes, two of the songs coming in at under three minutes long, the rest being around the three, four and five-minute mark, with only one clocking in at over seven minutes. Four of the tracks were lifted for single release, which wasn’t something you could say about, for example, Brain Salad Surgery, while the remaining numbers became daytime radio staples throughout 1979 and beyond, in Britain, across Europe, America and Canada, Australia, Scandinavia – most of the known world.

Article continues belowIn fact, it is rumoured that by the end of that year even tribespeople in the furthest-flung villages of deepest Africa were able to hum the refrain to The Logical Song and knew every word to the title track, taking special delight in the opening line, ‘Take a look at my girlfriend, she’s the only one I got’, much to the chagrin of their other halves in their huts.

That the album did so well was particularly impressive considering that it was Supertramp’s sixth long player, and its release came at the height of new wave and disco. Its domination of the single and album charts, and the airwaves, was quite unexpected by all concerned – by all, that is, except the band’s label boss, Jerry Moss.

“Jerry came down to the studio and said something about Peter Frampton – who was also on A&M – and us being likely to repeat his success,” recalls Peter Henderson, credited as co-producer alongside the band. “Basically, he said, ‘I think you guys are going to be next.’”

Supertramp had already been around for a decade by the release of their most popular record, having formed in 1969 around core members and songwriters Rick Davies and Roger Hodgson.

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

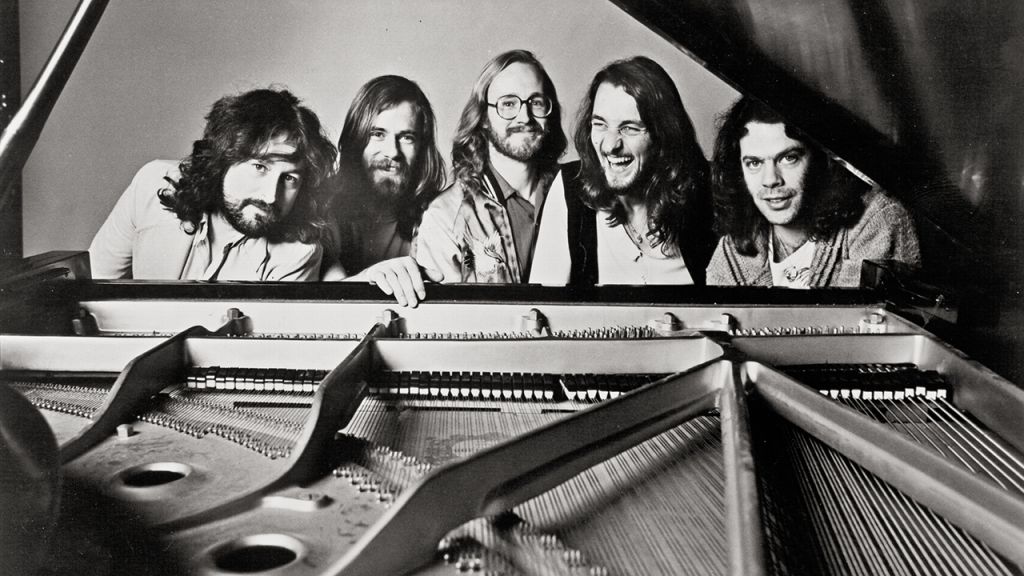

After two albums – 1970’s self-titled debut and 1971’s Indelibly Stamped – and several line-up changes, the group solidified around vocalists/keyboardists Davies and Hodgson, saxophonist John Helliwell, bassist Dougie Thomson and drummer Bob Siebenberg. This, the “classic” version of the band, established themselves as a cult attraction.

The first album by the five-piece, 1974’s Crime Of The Century, was hailed as a minor masterpiece of acerbic songcraft and dexterous musicianship, and it featured many of Supertramp’s finest songs, including School and Bloody Well Right as well as Dreamer, their first UK Top 20 hit. And although the follow-up, 1975’s Crisis? What Crisis?, wasn’t quite so well received, it did posit Supertramp as premier purveyors of polished, prog-ish studio pop-rock with thoughtful lyrics, joining the select pantheon that also included 10cc and Queen.

By the release of Even In The Quietest Moments… (1977), many of the bleak visions and dark portents about society expressed on the previous two records had come to pass in the form of punk, but Supertramp were able to weather the storm, and one of the songs, Give A Little Bit, became another huge and enduring hit.

But Breakfast In America eclipsed anything they had done before and skyrocketed the band into the commercial stratosphere. Supertramp were never a typical chart proposition or obvious stadium behemoths, with little of Gabriel-era Genesis’ live charisma, and none of the virtuoso pyrotechnics of Yes/ELP.

If they resembled anyone it was Pink Floyd in that they were anonymous musicians whose focus was the song, but they didn’t have the Floyd’s mythic allure. Instead, they were a motley crew – the bluff, working class Davies (from Swindon) and the public school-educated Hodgson (from Portsmouth), plus a Scot (Thomson), a Yorkshireman (Helliwell) and a Californian (Siebenberg) – who had been assembled for solely pragmatic reasons. They weren’t a gang of mates who had known each other since school days, and there was none of that sense of shared history.

And yet, by Breakfast In America, they had built up a certain rapport, having spent much of 1973-4 living together in the wilds of Somerset, in a cottage called Southcombe where they were joined by family, friends, crew and pets, as well as unofficial sixth member Russel Pope, whom John Helliwell considers to be “underappreciated nowadays – he helped Roger and Rick with lyrics, and he was good in the studio, too”.

In his sleevenotes to the reissued Breakfast In America – a two-disc affair containing the remastered album and a CD of live performances from 1979, available for the first time – MOJO’s Phil Alexander describes it as a “creative and supportive atmosphere”. Indeed, they had such fond memories of this period of enforced cohabitation that they tried to replicate the circumstances in America in 1978.

Supertramp’s music, the adroit performances and immaculate surfaces – what Helliwell has termed their “sophisto-rock” – was embraced even more readily by American audiences than British ones, and the band found themselves spending more and more time in the States, to the extent that Crisis? What Crisis? and Even In The Quietest Moments… were recorded there, in Los Angeles and Colorado respectively.

When they came to record Breakfast..., all five members had relocated full-time to the West Coast and bought apartments or houses there, but it was decided that the Colorado studio had been too sterile and so a new headquarters was found for Supertramp and co in Burbank, a home-from-home that was promptly given the name Southcombe. There, throughout 1978, they rehearsed the material and prepared the demos that would eventually be recorded at the Village Recorder studio in LA.

All very cosy, except that, according to some, they weren’t quite the unified, cohesive unit they had been back in Blighty four years before. Principal songwriters Hodgson and Davies had begun to pull in different directions, the former’s increasingly spiritual bent causing raised eyebrows in some quarters. The song Babaji from Even In The Quietest Moments… had alluded to Hodgson’s latest penchant, and there was no stopping him now.

“Rick was pretty down to earth whereas Roger was a bit more mentally… not

a higher plane, but spacey – he had spiritual yearnings,” says Helliwell, whose swirling sax provided Breakfast... with one of its signature sounds, along with those staccato Wurlitzer electric piano chords and Hodgson’s inimitable falsetto. It was in the build-up to Breakfast... that Hodgson fell in with a religious group who ran a commune in northern California.

“It was an organisation of spiritually-minded people run by this guy called Swami Kriyananda,” recalls Helliwell, “although his real name was Donald Walters. They were all very sycophantic towards him. It was weird. Eventually Roger bought a place nearby and Swami found him a wife and they got married.”

Some reports have it that there was tension between Hodgson and Davies over

a variety of creative issues, including the naming of the album (Davies apparently wanted to call it Working Title or Hello Stranger, the latter after a track that he had written) and the title song itself, which he allegedly didn’t want on the album.

Helliwell, however, maintains that, despite these rumours, the band were too intent on coming up with their greatest collection of material to allow personal or musical differences to get in the way. They even indulged in extracurricular activities together, such as playing football matches with local superstar and new best mate Rod Stewart, during which Helliwell acted as referee.

“There had started to be something slight, not a rift, but it was becoming apparent that Rick and Roger were quite different,” he admits, “but we managed to work well together. I don’t remember any animosity at all. We were just getting on with it, finding tunes that fitted together.”

They knew they were onto something special as soon as rehearsals began. “Even before we started recording we knew it was very strong musically,” says Helliwell of the early Breakfast In America sessions. Beatles engineer Geoff Emerick and his young assistant Peter Henderson had worked on Even In The Quietest Moments…, but it was with the latter that the band had hit it off best, so he was invited back, this time to co-produce (see panel). Supertramp had always had a reputation for meticulousness, and this was no exception.

“The sessions were even longer and more tedious than usual,” laughs Helliwell. “We spent hours and hours in the studio; it would take a week getting the right drum sounds.” He was particularly peeved at the presence of Hodgson’s device for producing the optimum air quality.

“Roger had this ionizer that he thought helped the air. I was convinced the fucking thing was giving me headaches so I kept turning it off, and he’d turn it back on. There were a few funny things like that.” But there were never, he insists, any punch-ups. “There have never been fisticuffs in this band,” he asserts. “Just tense silences...”

They may have been a quietly combustible mix, but the chemistry worked, with spectacular results. Virtually every song on Breakfast… was a melodic treat, at least half the tracks – Gone Hollywood, The Logical Song, Goodbye Stranger, Breakfast In America and Take The Long Way Home – being either singles or TV and/or movie soundtrack staples, while the remaining five ranged from the mellow concision of Casual Conversations to the more prog-ish and expansive Child Of Vision.

The beauty of Breakfast... was that it gelled as a whole, while it was to Hodgson and Davies’ eternal credit that they managed to make songs as quietly critical (of the US, and each other) as these so infectious and easy on the ear. Supertramp’s triumph, meanwhile, was the utter musicality and economical elegance of it all.

“We definitely didn’t want to go overboard, because we were conscious of some groups going on and on with long, long solos and complicated arrangements,” explains Helliwell. “We wanted everything to be tuneful and succinct. It was only when we finished it that we realised, ‘Wow, we’ve got something pretty strong here.’”

Breakfast… was an immediate success, reaching Number One in the US, Canada, Australia and Norway, while touring saw pandemonium down the front. Not backstage, though. “We still played darts before shows,” says Helliwell, who reveals that, at 34, he was simply too old to indulge in rock ’n’ roll excess.

“We were quite sober about it all, to be honest. We were more likely to go out for an Italian meal than have groupies draped over us or drugged parties in hotels.” Like a sort of British Steely Dan, Supertramp used the medium of “sophisto-rock” to comment on the culture with a detached, resigned air.

“That’s a good observation – we were looking from the outside,” says Helliwell. “I guess our songs are enigmatic and can be taken in many ways,” he concludes, “but they’re original and musical and have good tunes that don’t fit any particular category. People like them.”

Twenty million people, to be precise.

This feature originally appeared in Prog Issue 35, in April 2013.