"It was some extreme magic": How Stevie Nicks and Lindsey Buckingham saved Fleetwood Mac

With Stevie Nicks and Lindsey Buckingham on board, Fleetwood Mac’s 1975 self-titled album was the first record by what became the band’s most beloved and successful line-up

One evening in January 1975, at El Carmen, a Mexican restaurant in West Hollywood, John and Christine McVie were sitting at a table, with their margaritas, waiting for their bandmate Mick Fleetwood. Nervous anticipation was in the air, as they were all about to conduct what Fleetwood called a “chemistry test”.

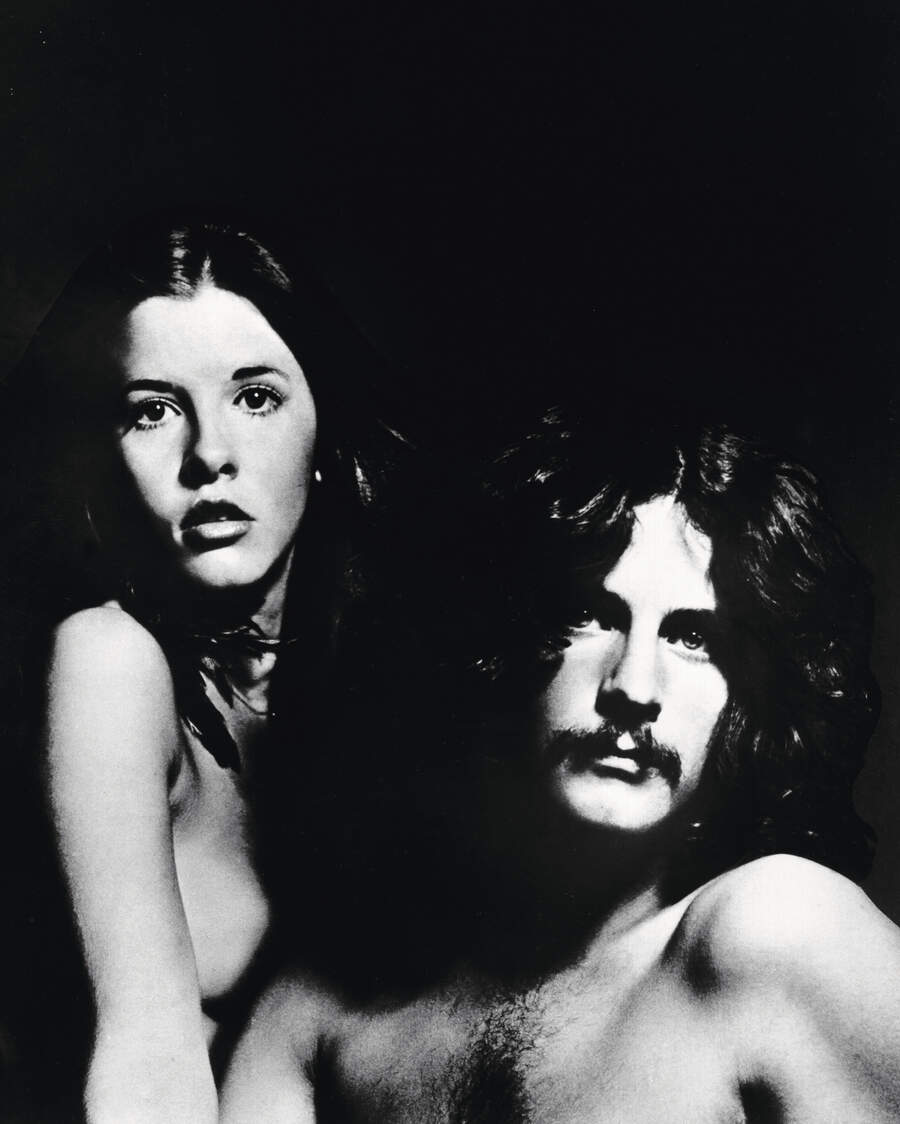

It was part one of an audition for two prospective new members of the band. A few months after hearing some tracks on this duo’s album, Buckingham Nicks, Fleetwood had invited the guitarist to join Fleetwood Mac, to replace the departing Bob Welch. But Lindsey Buckingham made it clear that he wouldn’t go anywhere without his musical partner and girlfriend, Stephanie Nicks.

Fleetwood drove them both to the restaurant. Christine McVie would later recall to Rolling Stone: “Mick said to me before the meeting: ‘Chris, if you don’t like the girl, then it’s not going to happen.’ I had never been in a band with another girl before, so it was important.”

As Buckingham and Nicks entered the restaurant, Christine was first struck by their physical appearances. “When Lindsey walked in I said to myself: ‘Wow, this guy is a god.’ And then Stevie walked in, laughing, so cute and so tiny, and I took an instant liking to her. She had this wonderful laugh and a fantastic sense of humour.” At the end of a drunken evening, Christine leaned over to Fleetwood and said: “Let’s do this.” “

Lindsey and Stevie were asked to play with us without ever playing a note,” Fleetwood said in the sleeve notes of Fleetwood Mac Deluxe. “It’s almost insane in retrospect considering the high risk, but somehow Christine and all of us just knew.”

Ironically, the week after they joined, Buckingham and Nicks were asked to a play a few shows in Alabama. Their album had become a sleeper hit in Birmingham, enough that they could sell out mid-sized halls. “We called it the Buckingham Nicks Farewell Inaugural Tour,” Nicks joked in 1976.

Although they’d already written songs for the follow-up to Buckingham Nicks, they had no illusions about where their future lay. Upon returning, they gathered for their first Fleetwood Mac rehearsal. Christine played them a new song she’d written, Say You Love Me. When she hit the chorus, Lindsey and Stevie immediately piped in with harmonies. It was the birth of a singular vocal blend that would come to rival The Beatles, Crosby, Stills & Nash and the Eagles.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

In the BBC documentary Songbird, McVie recalled that moment: “It just shot off like firecrackers. When the chorus came, they came in with this incredible three-part harmony. We all got enormous goose bumps. From there we went straight into making this album [1975’s Fleetwood Mac], and the whole experience was this wonderful giant discovery.”

“It was some extreme magic,” Fleetwood wrote in his autobiography. “Hearing us all together for the first time that way is the reason we’re still talking about this album after all this time.”

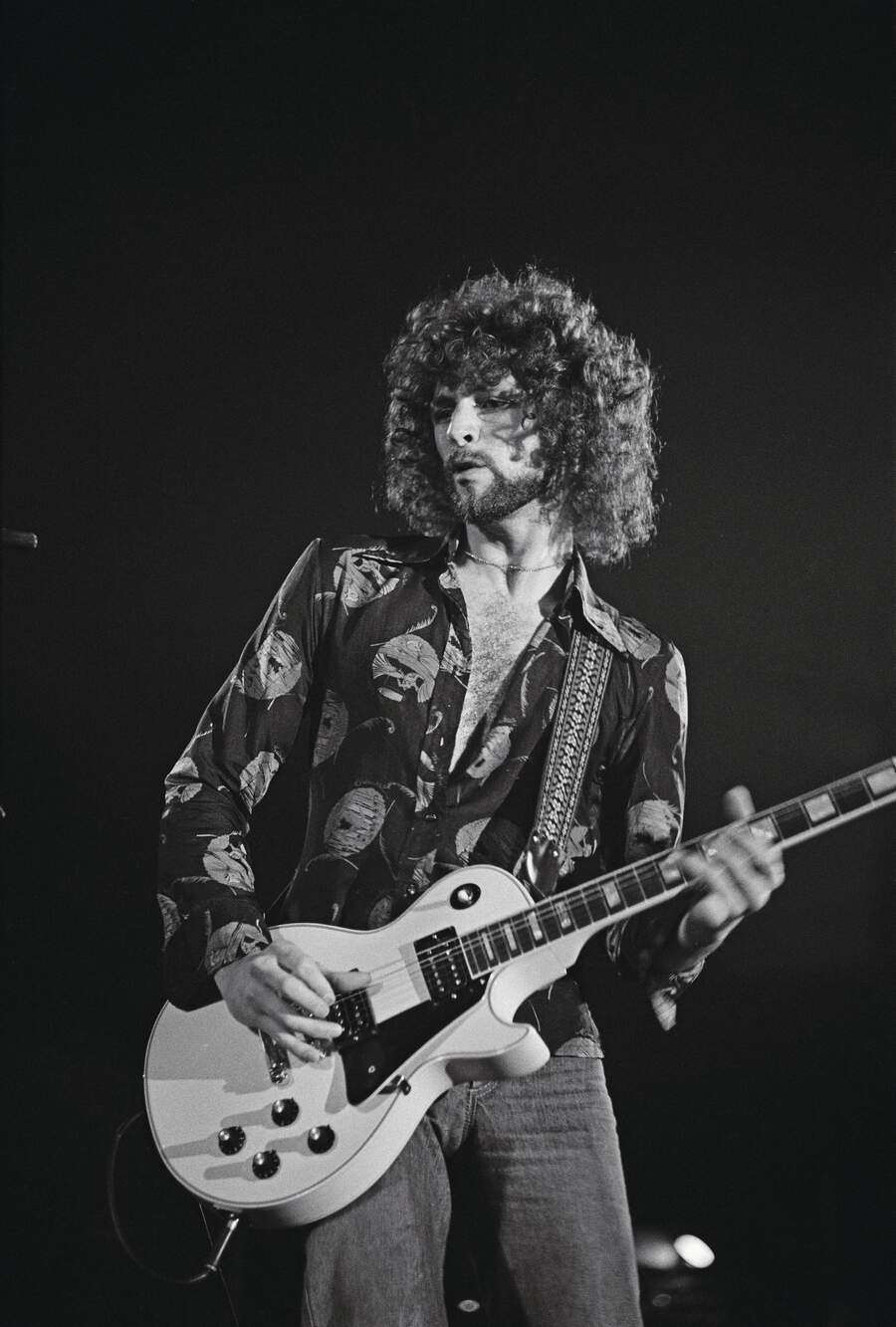

The ‘extreme magic’ is even more remarkable when you consider that in 1974 Fleetwood Mac were already six years and 10 records deep into a career that was marked by stylistic left turns and perpetual personnel changes. When they debuted in 1968 as Peter Green’s Fleetwood Mac, they were part of the John Mayall-led British blues boom, just another gritty quartet in blue jeans and flannel shirts, playing a mix of originals and covers of songs by American bluesmen such as Howlin’ Wolf and Elmore James.

In the years after, thanks to the addition of keyboard player/vocalist Christine Perfect (soon to marry John McVie), the band had evolved with the times towards more song-based melodic rock. Still, trying to hold on to some of the old blues pedigree while changing made for sometimes erratic albums.

“The style had to change because I was a keyboard player,” McVie told the Sunday Express in 2004. “And it developed a more radio-friendly bent. It was thrilling, and I have to say to this day, it still kind of is, knowing I did that.”

Mick Fleetwood had recognised Christine’s gifts, encouraging her to “launch out and do something a bit commercial” with her songwriting. On her early compositions like Morning Rain, Remember Me and the shoulda-been-a-hit Just Crazy Love, she kept one foot – or hand – in her formative boogie blues and let her inherent feel for melody bloom.

At the same time, the band were shedding guitar players almost every other album. Peter Green left in 1970, a casualty of too many acid trips and an uneasy relationship with fame. Reflecting on his departure, Fleetwood told Classic Rock: “We got the sense that he was struggling when it was too damn late. And I don’t think we would’ve been equipped to help him anyhow. He intimated that he was done. We were on tour and he said: ‘We’ve got to give all our money away.’ And he disowned himself, disowned what he’d done. Said that he’d stolen everything he’d ever created. Of course, it’s nonsense. But he left very responsibly. He didn’t dump on us.”

Sadly, in the decades after, Green never recovered his momentum as a guitarist.

A year later, Jeremy Spencer wandered off to join the religious cult Children Of God, changed his name to Jonathan and shaved his head, a move that Fleetwood described as being “like a bad B-movie”. Danny Kirwan went next, imploding in an alcoholic, guitar-smashing tirade. Dave Walker was in the band for less than a year before being asked to leave because his style “didn’t fit in”. Bob Weston was fired for canoodling with Fleetwood’s wife (more on that in a minute). And in 1974, triple-threat singer/guitarist/songwriter Bob Welch became the latest to give notice.

Reflecting on this revolving door of guitar players, Christine McVie credited Bob Welch’s time in the band for inspiring the vocal harmonies that became a part of the classic sound. “In the past, no one did harmonies,” she told Mojo in 2017. “Danny Kirwan would be: ‘Ooh no! I don’t want harmonies.’ It was only with Bob that we started to develop a three-part harmony vibe. Bob had this honey voice, and so did I. We sounded great together and worked well in the studio.”

In 1977, McVie added vocals to Welch’s biggest solo hit, Sentimental Lady.

Further complicating the band’s shifting identity was the strange episode of the counterfeit Fleetwood Mac.

In 1973, two weeks into a US tour behind Mystery To Me, Mick Fleetwood discovered that guitarist Bob Weston was having an affair with his wife, Jenny Boyd. He fired Weston, cancelled the rest of the tour and announced that the band was splitting up. Meanwhile, their manager, Clifford Davis, was left with outstanding tour commitments and a threat to his professional reputation. He claimed that he owned the name Fleetwood Mac, and assembled another group from various members of Curved Air and Manfred Mann. ‘The New Fleetwood Mac’, as they dubbed themselves, resumed the US tour dates. The original group filed a lawsuit against Davis.

Because ownership of their name was entangled in their contract with Warner Brothers, Welch moved back to Los Angeles to sort things out with entertainment lawyers. Fleetwood and the McVies soon followed. “The record company was here, and communication is easier in America,” John McVie told Melody Maker at the time. “We had to get out of England because we were going crazy, driving up to London every day and spending all our time in an office.”

The case of the ‘fake Fleetwood Mac’, which was eventually settled out of court, sidelined the band for almost a year. More significantly, it relocated them from overcast Britain to sunny California. Gold – and multiple levels of platinum – was in them thar hills.

Also crucial to the band’s transformation was producer Keith Olsen. A month before the fateful meeting at the Mexican restaurant, Fleetwood had been scouting around LA for a studio to record the next album. When he met Olsen at Sound City Studio in Van Nuys, it was really just to check out the space. Olsen cued up two songs – Crying In The Night and Frozen Love - from a record he’d produced called Buckingham Nicks.

It hadn’t set the world on fire, but Olsen’s production and the intimate sound of the boyfriend/girlfriend duo impressed Fleetwood. He described the songwriting and the vocal interplay between the two as sounding “like Fleetwood at that moment, the guitar playing. Lindsey’s style was so stunning and unique. It was what hit me first, and it hit me hard,” he told Rolling Stone. “That hour and a half spent in Sound City changed everything.”

It reminded Fleetwood of how he and John McVie would often talk about music in terms of an ‘It factor’. In the deluxe version sleeve notes, he said: “We’d always say, ‘Yes, but does it have It? It is whatever makes music and people connect. Ultimately, It is what it’s about. And It is what made Lindsey’s guitar playing and that vocal blend with Stevie stay with me.”

With the duo now in the band, and adding extra ‘it’ factor, Christine McVie felt a new challenge. “I sensed I had to upgrade my game as a songwriter to keep up with them,” she said. “I wanted to impress them. So I got on my piano in the tiny bedsit that John and I rented in Malibu, right on the ocean. And I sat in there and wrote Over My Head and Warm Ways. I also found Lindsey and I could co-write. World Turning was our first song together and a strong start.”

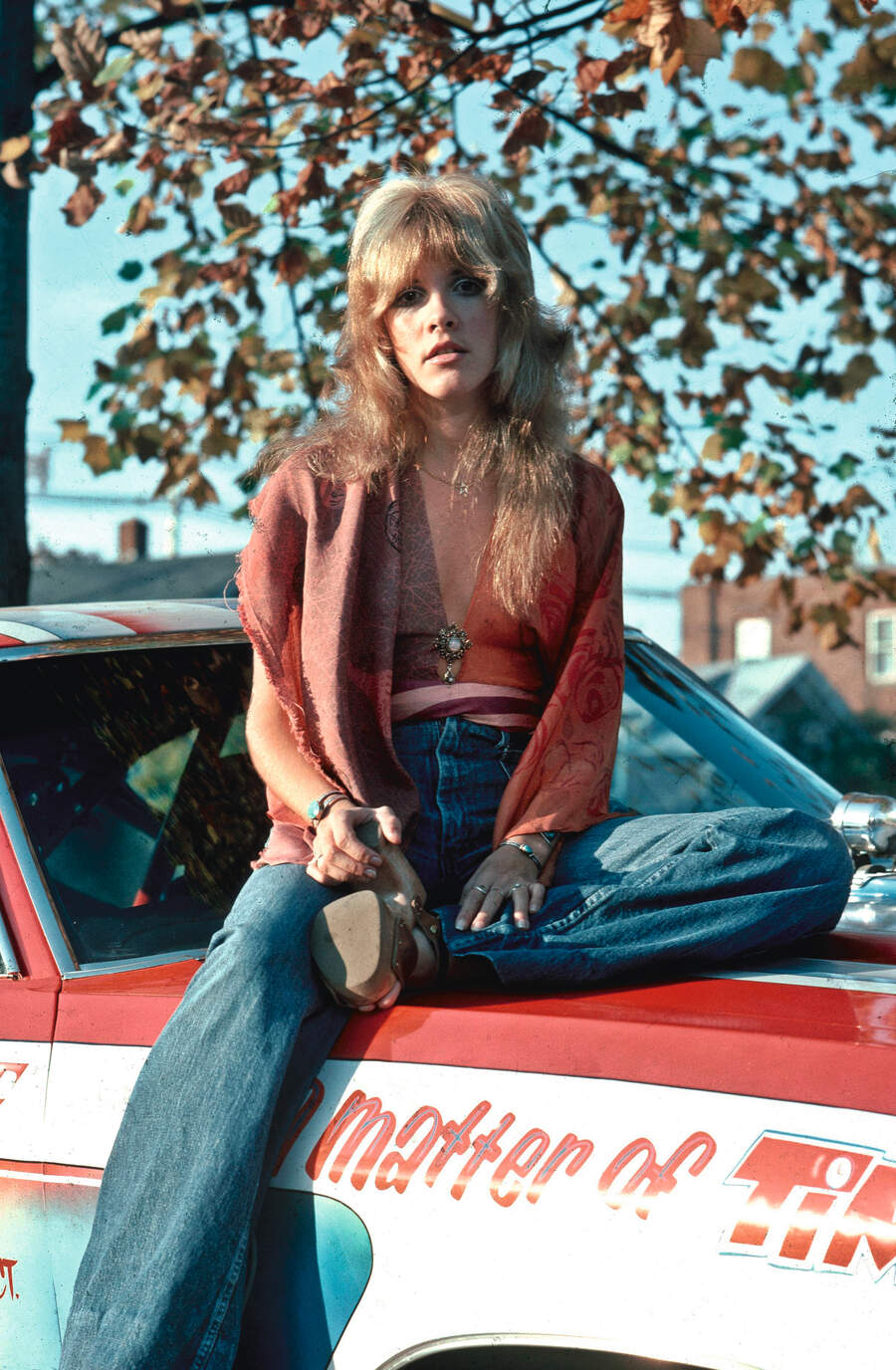

As would happen over the next five years - the band’s most fertile and commercial period - it was a friendly three-way competition for songwriting on the albums. Buckingham brought in I’m So Afraid and Monday Morning, the latter leading off the album with its message of a bright new horizon. His songs had been intended for a second Buckingham Nicks album. As had the two hits that Nicks brought. Both would become Fleetwood Mac standards: Landslide and Rhiannon. The first song came out of a period of limbo after label Polydor had dropped Buckingham Nicks.

“It was horrifying to Lindsey and I because we had a taste of the big time,” Nicks told me in 2003. “We recorded in a big studio, we met famous people, we made what we consider to be a brilliant record and nobody liked it.”

In the period after, Nicks worked as a waitress and a cleaning lady to help support them, while Buckingham went on the road playing guitar with Don Everly. She said: “While Lindsey was out, I was staying with a girlfriend in Aspen. I’d gotten to the point where it was like: ‘I’m not happy. I am tired. But I don’t know if we can do any better than this.’ So during those two months, staring up at the Rocky Mountains every day, I made a decision to continue. Landslide was that decision.

She continued: “In one my journal entries it says: ‘I took Lindsey and said: We’re going to the top!’ And that’s what we did. Within a year, Mick called us and we were in Fleetwood Mac, making eight hundred dollars a week apiece. Washing hundred-dollar bills through the laundry. It was hysterical, like we were rich overnight.”

Rhiannon was inspired by bibliomancy, a mystical practice that held that if a book is picked up and opened to a page at random, the first word or sentence one sees will reveal some kind of epiphany. To test it out, Nicks picked up a novel she’d found at a friend’s house, lying on the couch.

“It was just a stupid little paperback,” she told me. “It was called Triad [written by Mary Leader] and it was all about this girl who becomes possessed by a spirit named Rhiannon. I read the book, but I was so taken with that name that I thought: ‘I’ve got to write something about this.’ So I sat down at the piano and started this song about a woman that was all involved with these birds and magic.

“I still have the cassette tape of when I was first writing it,” she continued. “Lindsey came in and I said: ‘We have to go to a park and record the sound of birds rising.’ And he looked at me like I was crazy. I said: ‘Don’t you think Rhiannon is a beautiful name?’ And he said: ‘Yeah, it is a beautiful name.’”

On a less mystical but equally remarkable note, the rhythm section of drummer Fleetwood and bassist John McVie adapted to this new complex pop material with chameleon-like ease. The songs were stylistically miles away from the meat-and-potatoes 12-bar blues progressions that had first bonded the duo.

As Fleetwood noted: “If you change members in a lot of other big bands, I don’t think they change the essence, the musical identity, as much as we have. Put on this album and put on Live At Chess Records with Peter Green. It’s stunning to think that can be the same band. I feel like there are other bands that have survived, but no other that changed as much, and somehow survived as well. I think John and I hanging in there allowed this funny, diverse band to keep changing and evolving. It was really all three of the writers’ songs – and our balls – keeping it going.”

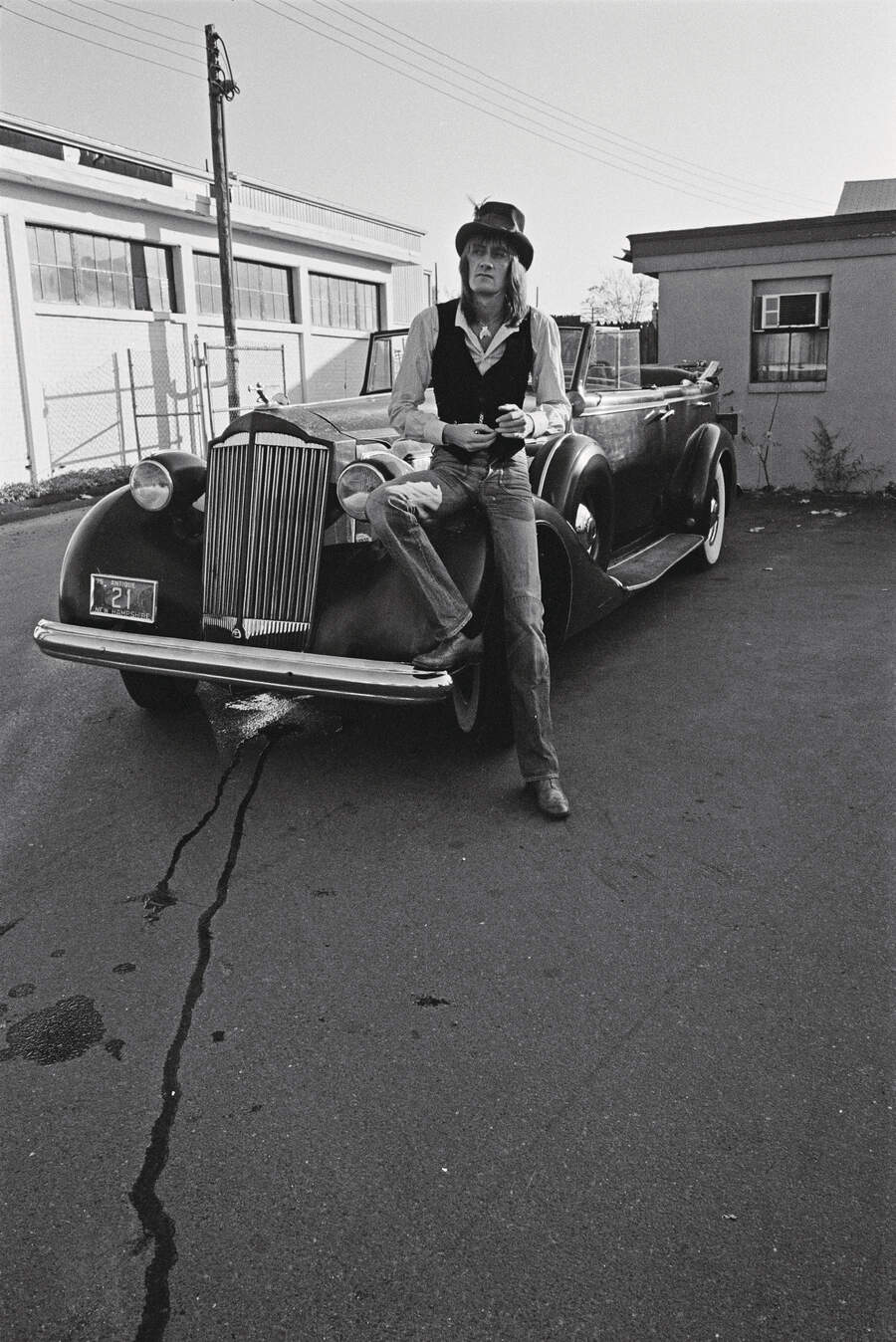

As recording at Sound City continued over the early months of 1975 in what Fleetwood called a “Peruvian atmosphere”, the hyper-confident Buckingham emerged as the true producer of the sessions. A multi-instrumentalist, he wasn’t shy about demonstrating drum and bass parts to Mick and John – a habit he soon learned to use sparingly, especially with the combative McVie. Still, they had to admit, the 25-year-old guitarist had brilliant ideas.

“It’s always been about the style and the architecture and the bigger picture of it,” Buckingham told me in 2021, talking about his approach in the studio. “That process of being able to discover things, just as you’d slap paint on a canvas, building up layers, I find that to be very exciting and very inspirational. It really began before Fleetwood Mac, when I was making the demos for the Buckingham Nicks album. I was basically taking the lead from how Les Paul had bounced tracks back and forth and playing everything myself.”

With the Say You Love Me, Monday Morning and Rhiannon now on tape, the band agreed that something special was happening. But would the world – much less the record company - agree? Fleetwood, who’d taken over as the band’s manager after the lawsuit with Davis, went to see Mo Ostin, head honcho of Warner Brothers. The drummer knew that the label’s interest in the band might be waning. Their previous album, Heroes Are Hand To Find, had not sold well. He also knew that, talent aside, Buckingham and Nicks were relative unknowns who’d been dropped from their previous label.

“So I took some of the tracks to Mo,” Fleetwood recalled in the sleeve notes, “and said: ‘If you don’t hear something special here, will you let us go? Because I really believe this is something special.’ It was a kind of naive threat. And of course Mo loved it. Then I said: ‘This is so special, I think we need to go out as a band.’ Because I knew when the record came out, we had to be ready for whatever came. Also, we really needed some pocket money.”

Playing shows before an album is out isn’t typical protocol. “Warner Brothers thought it was stupid,” Fleetwood wrote in his autobiography. “They thought we were committing suicide by playing without new music to sell.”

But on May 15, 1975, two months before the release of the Fleetwood Mac album, the soon-to-be-classic line-up of Fleetwood Mac took the stage for the first time, kicking off a short tour with a show at the Civic Center Theatre in El Paso, Texas. The set list was carefully constructed as a kind of historical survey of the band, which meant Rhiannon and Say You Love Me were next to Oh Well and Hypnotized.

“We opened for Loggins And Messina, Ten Years After, The Guess Who,” Fleetwood wrote. “We were making three thousand dollars a gig. John Courage [the band’s sound man] and I used to give back money to the promoters in the dressing room after the show, so they’d stand by us when we needed them later. At every stop, we told people about our next record and said we’d be back to play again after they’d heard it.”

Christine recalled: “We started out in some half-empty halls, but right away there was something happening on stage that ignited between the five of us. Even back then before all the social media, there was word of mouth and good reviews. Gradually, the audience heard the buzz and started showing up.”

All of this new excitement might not have meant anything without the solid foundation the band had built over the previous seven years. In 1976, Fleetwood told Melody Maker: “In the States, our albums pretty much sold in the 200-250,000 range. We were always appreciated and we never lost anyone. The cult kept growing. Wide-scale acceptance has always been around the corner. We started here at the club level and worked all the way up through small halls, second and third billings, headline status and some outdoor things.”

“Me, Chris and Mick have been working for a long time,” John McVie added in the same interview. “We’ve eaten every day and had money for smokes. I’m proud we pushed ahead. The success now makes some justification for the effort of the past.”

The last hurdle was convincing Warner Brothers that there was a hit single on the record. “Their attitude was still ho-hum,” Fleetwood wrote. Given the bounty of now-classics on Fleetwood Mac, it seems unthinkable now that the label couldn’t hear beyond past perceptions of what Fleetwood jokingly called “a band that would pay the company’s lighting bills”.

Radio also thought of them as a middle-tier albums band. So they brought in Deke Richards, who’d produced the early Jackson Five hits at Motown, to give Over My Head a bright, snappy new mix that would leap out of car radios. It worked.

Fleetwood Mac was released on July 11, 1975. After the first month, it had sold 400,000 copies, more than any other in their back catalogue. By November, Over My Head was in the Top 10. By Christmas the album had gone gold. Recognising the band’s reinvention, reviews were almost unanimously positive. Phonograph said the “diversity and electricity helped crystalise Fleetwood Mac as a song band”. Circus dubbed it “an easy-going, immensely playable album”. NME was a lone objector, griping about what they deemed Buckingham and Nicks’s “MOR whimsy” and “cloying cuteness”.

A slow-burn hit, the album reached No.1 on the Billboard 200 more than a year after entering the US chart (it reached only No.23 in the UK), and was the second-biggest album of 1976, outsold only by Frampton Comes Alive. In 2018 it was certified seven-times platinum. And of course, it set the stage for the decadedefining juggernaut just up ahead - 1977’s Rumours.

“There was such a sense of excitement,” Christine told David Wild. “You didn’t want to leave the studio. We are so diverse in so many ways, including that we have men and women, Americans and Brits, and three main writers with very different styles of writing. Yet we’re all grounded in a wonderful way by the rhythm section. We all sing on each other’s songs. And the songs themselves are so diverse. Yet there’s always a thread that catches all the songs together and makes all the pieces fit.”

“We just played everywhere and we sold that record,” Nicks told Uncut. “We kicked that album in the ass.” Buckingham told NME: “Early on, soon after joining Fleetwood Mac and making that first album, I realised that we were the kind of group who didn’t – on paper – belong in the same group together. But yet that was the very thing that made us so effective.”

“This is the album that’s the line in the sand where you can see the biggest and most significant change,” Fleetwood said in the sleeve notes. “It came along at a time when it could have been the end, but instead it became a new beginning.”

Fleetwood Mac’s 1975-1987 box set is out now via Rhino.

Bill DeMain is a correspondent for BBC Glasgow, a regular contributor to MOJO, Classic Rock and Mental Floss, and the author of six books, including the best-selling Sgt. Pepper At 50. He is also an acclaimed musician and songwriter who's written for artists including Marshall Crenshaw, Teddy Thompson and Kim Richey. His songs have appeared in TV shows such as Private Practice and Sons of Anarchy. In 2013, he started Walkin' Nashville, a music history tour that's been the #1 rated activity on Trip Advisor. An avid bird-watcher, he also makes bird cards and prints.