Cigarettes, alcohol and heroin: the inside story of Black Sabbath’s Paranoid

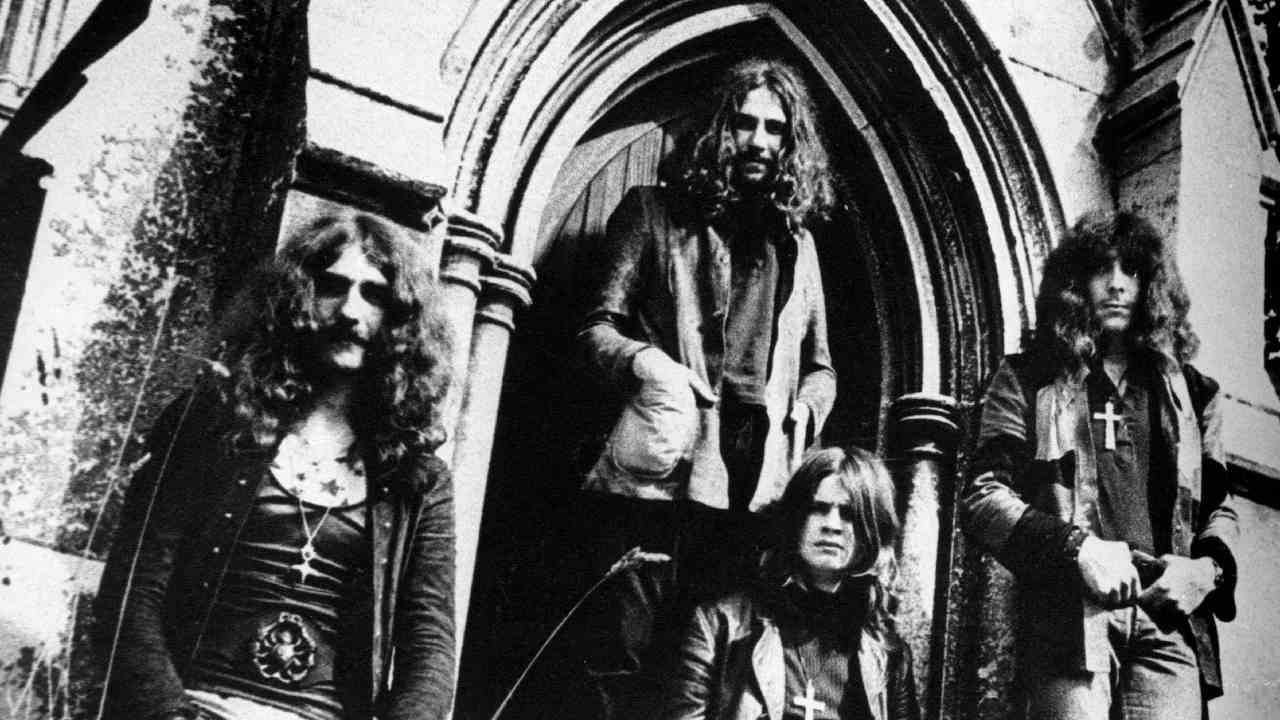

Black Sabbath’s debut album staked their claim as the Godfathers Of Metal. But follow-up Paranoid turned them into stars

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

Today’s metal bands are a bunch of slackers, relatively speaking. You think releasing an album every three years is hard work? Imagine what it was like four decades ago, when heavy metal barely existed, studio technology was practically steam-driven, and they still made you record two albums a year…

“If a band was starting to break, they told you, ‘You have to go back in the studio’,” recalls Black Sabbath drummer Bill Ward. “Our first album came out in February 1970… and four months later, they said we had to do another one!”

Fortunately, Black Sabbath – Bill plus singer Ozzy Osbourne, guitarist Tony Iommi and bassist Geezer Butler – were made of stern stuff. For starters, they came from the mean streets of Aston, a Birmingham suburb that had been bombed to smithereens in World War II, just five years before they were born. You didn’t whine about lifestyle options if you were a teenager in Aston in the 1960s: you were too busy concentrating on not being stabbed for having long hair.

The urge to escape their background had turned Sabbath into a highly disciplined group by the time their self-titled debut album was released in 1970.

“We worked hard,” says Bill. “We would get up early and be playing by 9.30am. We had a rehearsal room in Birmingham until lunchtime and then we’d go back to Tony’s house and drink tea, eat toast and scrounge cigarettes off his mum. Then we’d be playing a gig – almost every night.”

Although the Black Sabbath album had made an impact, the band members still experienced shudders of fear when they thought about returning to the horrendous jobs they’d had in the late 60s.

“I drove a lorry in a cement works,” remembers Bill. “It was really hard graft: I had to lift hundredweight [about eight stone] bags of cement. I used to have one under each arm and another on my back.”

Sign up below to get the latest from Metal Hammer, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

- Tune into Townsend Music’s massive CD and vinyl sale

- The best metal guitars 2020: Get ready to shred with our essential list

- Less noise, more rock with the best budget noise cancelling headphones

- Loudest Bluetooth speakers: the best speakers for maximum noise

All this meant that Sabbath were determined to make their second album a definitive statement. They looked around for a different way to make the LP, as life in Birmingham wasn’t conducive to high-quality songwriting.

“We wanted to try something different – to be a little bit isolated,” recalls Bill. “There were too many distractions. We were starting to become quite well-known, both in the Midlands and throughout the rest of England, so we rehearsed in Monnow Valley in Monmouthshire, Wales.”

Getting it together in the country is a time-honoured way of focusing on the music, and it certainly worked for Sabbath, who once across the border constructed a set of near-flawless songs. The pressure of coming up with the goods and avoiding the dole queue (or worse, factory work) was relieved a little by a switch to a supposedly professional management team.

“We’d done the Paranoid demo and moved managers to Tony Hall and Patrick Meehan,” Bill explains. “We were pretty much hand-to-mouth before that point: the only time we started to see any money was when we hooked up with Patrick. We’d get £500 after a gig, and we’d be like, ‘Fuck! You’re kidding?!’ We hadn’t seen that much money in two years. In 1970, that was huge money. When we wanted money, we’d just go and ask Pat for some. There was no accounting or anything.”

Unaware of the sinister implications of their new management’s financial practices, the band knuckled down to recording the new songs. It was here that their apprenticeship at hundreds of gigs per year came into play, with the material efficient and unforgettable.

“We were very tight,” notes Bill. “We’d been playing together for over two years; we’d been through Germany and Switzerland. When we played together, we wanted to improve and be really good. You have to remember, this was a very good live band coming into the studio for Paranoid. The producer, Rodger Bain, has to be praised too, but I think we delivered our aggression and on stage dynamics in the studio – perhaps not completely, but mostly.”

Thanks to this disciplined approach, the songwriting went smoothly, says Bill:

“Geezer and Ozzy shared the lyrics and we all participated in the arrangements, while Tony had the riffs and presented them to us. We’d all look at the parts and put them together. Some things were so obvious that we’d play intuitively: there was a mental connection between us.”

Any drummer who has ever attempted to replicate Paranoid’s first song, War Pigs, will know what Bill means. There’s a subtle groove behind the leaden, classic riff that anchors the song, which is as heavy lyrically as it is sonically. Famously, War Pigs has always been credited as Sabbath’s first political song, as Bill clarifies:

“War Pigs is a protest song: not anti-war, but against the people who create the wars, and put all the young men and women in harm’s way. War is an incredible responsibility, and they know that people are going to get killed. In this song, we were talking about the Vietnam war. The counterculture of a few years before had slammed the same political voices, but Sabbath made a far more aggressive musical statement. Ozzy’s delivery on this song, and all these songs, is just brilliant.”

Wise words, as Ozzy’s doom-laden monotone suits the songs perfectly. A singer with a wider range wouldn’t have suited the apocalyptic lyrics on this and the other Paranoid tunes. Still, Sabbath have come in for some mockery over the decades for Geezer’s decision to rhyme the word ‘masses’ with, er, ‘masses’ in the first two lines of the song. Asked if he’s aware that the occasional snigger is aimed at that spectacularly minimal piece of composition, Bill guffaws.

“Oh dear. I’m actually laughing because I never knew that. What else was he going to use to rhyme with ‘masses’? ‘Asses’?”

After the colossal opening song, since covered by many metal and rock bands (“I loved Faith No More’s version of War Pigs,” says Bill), comes the album’s title track – one of the band’s best-known to this day. But it nearly didn’t come about, reveals the drummer.

“Rodger Bain, the producer, suggested that we might think about doing a commercial song. We were adamant that we wouldn’t, but he said, ‘See what you can come up with,’ so we went off on our lunch break and when we got back, Tony had come up with the riff. I sat down, Ozzy went to his mic, Geezer strapped on his bass and we started playing. What you hear on the album is literally 25 minutes of work! The only thing we added was Tony’s guitar solo, which he recorded the next day. I couldn’t believe how that song went off: everybody went nuts about it.”

A surprise for the Sabbath fans of the day was Planet Caravan as it’s a much subtler, even gentle composition which focuses on textures rather than aggression.

“We always knew we could do softer things,” explains Bill. “We were already getting an inkling that we could play other things than War Pigs. We put Ozzy’s voice through a Leslie speaker and it sounded really cool. Tony was playing some nice jazz chords, too: a lot of people might not know that he’s a great jazz guitarist.”

The next three songs – Iron Man, Electric Funeral and Hand Of Doom – form the Armageddon of heavy music, 70s-style: nothing like them existed at the time, and they’ve inspired just about every doom metal band around today. Metal musicians are quick to acknowledge the massive effect of the songs: for example, Opeth’s Mikael Åkerfeldt once told Hammer, “the terrifying voice at the beginning of Iron Man almost made me shit myself”. Bill chuckles at such tales.

“Yes,” he admits, “it’s a dark album. I like the dark! Geezer loves the macabre, as does Ozzy, and Tony loves to play dark. I was definitely in the right band…”

Hand Of Doom has a particular resonance for Bill, as its obscure refer- ences to heroin remind him of his own, thankfully brief dalliance with the drug.

“It’s a sad song,” he muses. “Lyrically, it’s raw, and the lyrics do include drug use, but I’d stopped using heroin by then. I hated it. My drug of choice was alcohol and cocaine. I also loved speed, although I haven’t used it in nearly 30 years. I’m sure there’s references in the songs to people dying from this horrible fuckin’ disease.”

The penultimate song on this immense album, Rat Salad, contains a virtuoso drum solo from Bill. “I had three minutes to fill, so I tried to put as many examples in from my big onstage solo,” he explains.

After the album recording, Sabbath returned to Birmingham and their endless gigging schedule. The final mix of Paranoid was very much of its time.

“It’s a realistic album,” says Bill. “We were blacking out the microphones a lot from slamming on the drums, so the sound could use a lot of improvement. But it’s a natural sound: it’s what we did back then.”

And so Black Sabbath took a step up to another professional level – one where they were operating at the peak of their powers. Oh, and also one where they would get royally ripped off by their new manager.

“We were taken for a ride financially,” explains Bill. “We couldn’t afford a lawyer. I was busy looking at the women’s backsides and everybody was drinking cognac, so it was all fine by me. It was only a few years after Paranoid that we started asking, ‘Er, where’s all the accounting?’”

Let that be a lesson to all young bands: when it comes to the small print, the war pigs always have the power.

Published in Metal Hammer #210

Black Sabbath – Paranoid: Super Deluxe Edition

Epic 5-disc Super Deluxe 50th anniversary edition of Black Sabbath’s iconic second studio album, featuring War Pigs, Iron Man and the title track. The box set also includes a selection of live recordings and a quad stereo mix of the album. Released on October 9 and available to pre-order now.

Joel McIver is a British author. The best-known of his 25 books to date is the bestselling Justice For All: The Truth About Metallica, first published in 2004 and appearing in nine languages since then. McIver's other works include biographies of Black Sabbath, Slayer, Ice Cube and Queens Of The Stone Age. His writing also appears in newspapers and magazines such as The Guardian, Metal Hammer, Classic Rock and Rolling Stone, and he is a regular guest on music-related BBC and commercial radio.