A Brief History Of Harvest Records

Relive the magic of some of greatest imprints of all-time in Prog’s new bite-sized label guide.

When Morrissey took to the stage for his only UK concert of the year last November, his band were wearing T-shirts that sported the legend ‘Fuck Harvest’.

Morrissey’s recent altercations with the revived label that dropped him after his July 2014 album World Peace Is None Of Your Business seem very much at odds with the paternal, often whimsical approach to its artists in its 70s heyday. (“It really was a very friendly and very cosy world,” Rob ‘Edgar’ Broughton said in March 2006.)

Vying with Phillips’ Vertigo as the most loved of all the corporate progressive offshoots, EMI’s Harvest Records’ place in the collective memory is secured today thanks to its connections with Pink Floyd and their former leader Syd Barrett. While many rightly wax lyrical about the efforts of Tony Stratton-Smith at Charisma, or Chris Blackwell at Island, Harvest had a similar quirky, cool cachet – and it had Floyd, the biggest-selling band of all the labels during the 70s.

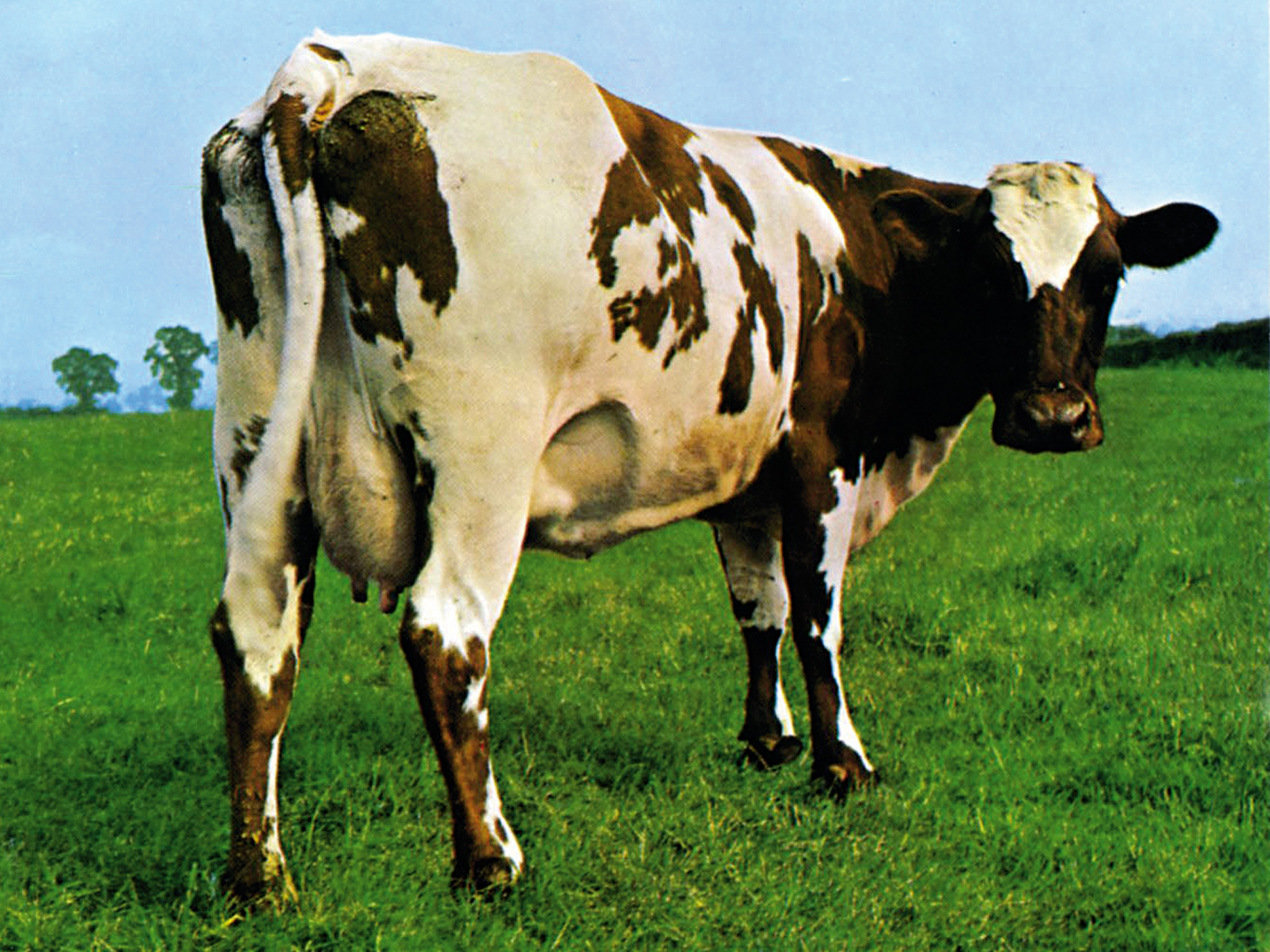

But as always with these strange, eccentric, boutique labels, the roster went far deeper and had a lifespan far greater than just Floyd and Barrett. Although Pink Floyd were to give Harvest their first and last No.1 albums (Atom Heart Mother and The Final Cut), there was so much more besides. The diversity and strangeness of Harvest acted as a template for many other major labels to launch their own imprints. It may not have had the ‘we’re all up a tree/in the pub’ ethos of Island/Charisma respectively, but it certainly gave space to acts who would never have been heard otherwise.

**HOW IT BEGAN: **

Manchester University economics graduate Malcolm Jones joined EMI in 1967 as a trainee manager. Dealing initially with licensed repertoire, Jones worked with 60s industry luminaries such as Denny Cordell and Mickie Most. His A&R ears became feted and so the suits responded favourably to his suggestion in early 1969 that EMI needed a new label to cater for the underground scene, inspired by Decca’s Deram imprint, and Chris Blackwell’s Island, arguably the first independent label. Jones wished to bring together acts such as Floyd (who were recording for Columbia) and Deep Purple and Barclay James Harvest (who were on Parlophone).

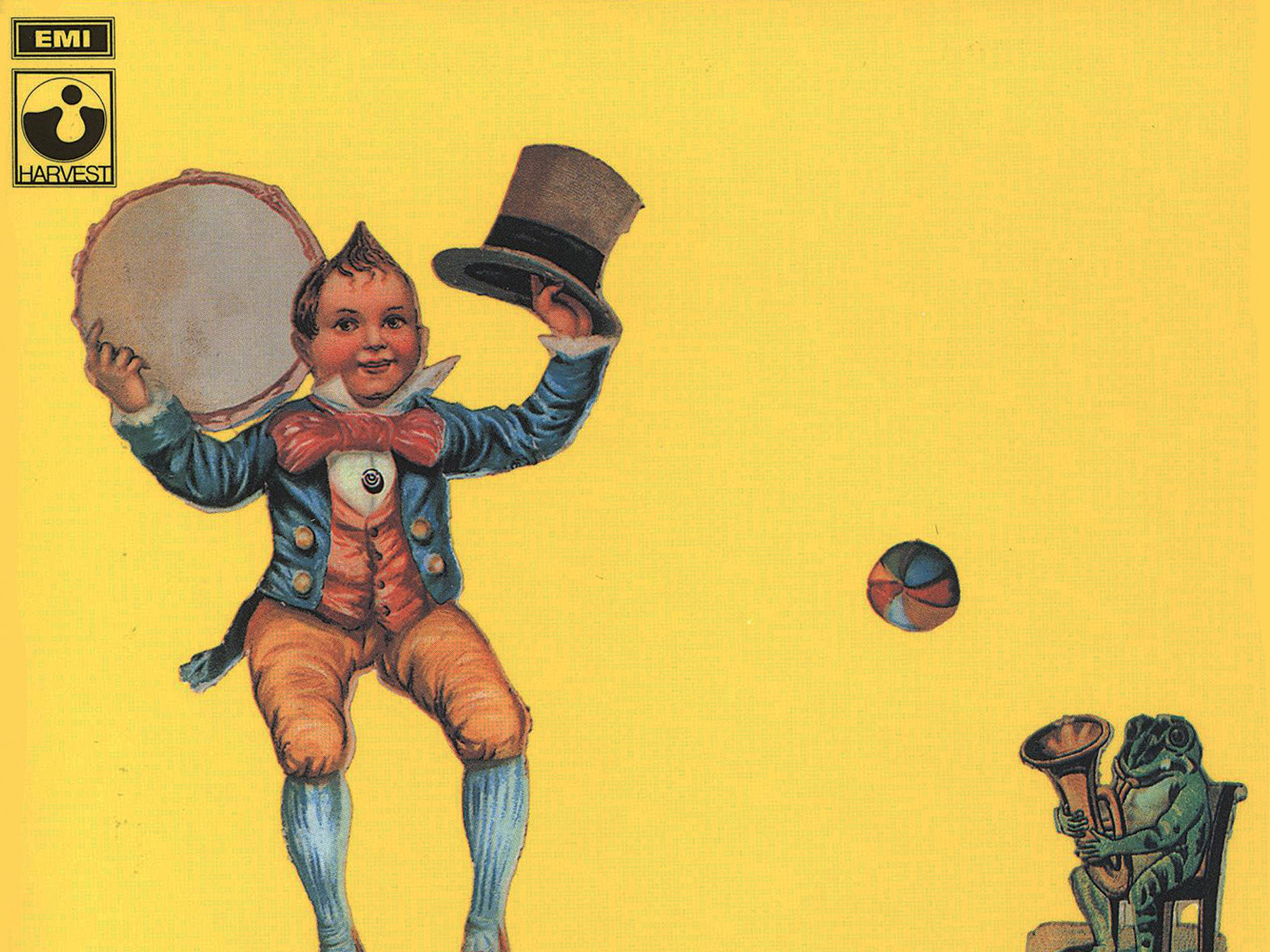

Jones asked potential artists for the new label to write down their ideas for a title. Allegedly, Barclay James Harvest scrawled ‘Harvest’ and Jones approved. Roger Dean, who by then was just establishing himself as the go-to artworker for progressive album covers, designed the legendary logo.

The latest news, features and interviews direct to your inbox, from the global home of alternative music.

What differentiated the label was its A&R policy, which was bolstered by the involvement of Andrew King and Peter Jenner, the men behind Blackhill Enterprises. They were the original managers of Pink Floyd and, by 1969, they were overseeing the waywardly haphazard solo career of its former leader Syd Barrett, as well as organising through their promotion agency the enormous free concerts in Hyde Park that so captured the mood of Britain in the late 60s. They were also responsible for the disparate carnival of underground bizarre that came along to Harvest, led by the outré-freaks Edgar Broughton Band.

“I thought I had golden ears, I thought everything I heard and quite liked would be a hit,” Peter Jenner told NME in 1989. “This is money for old rope mate! Easy. Good game! Loads of money! But after that… Harvest Records! Not that they were compete turkeys but it became much harder work. Barclay James, Roy Harper, Edgar Broughton Band, Kevin Ayers, they all did quite well. But we had a band called the Forest who were complete stiffs, and the Third Ear Band were never easy – bunch of hippie folkies.”

King and Jenner also brought in Michael Chapman and Bridget St. John. Abbey Road engineer Pete Mew recalls that the pair were: “Wonderfully eccentric. As Andrew King said to me a few years ago, ‘I used to get two per cent for bringing the Rizlas.’”

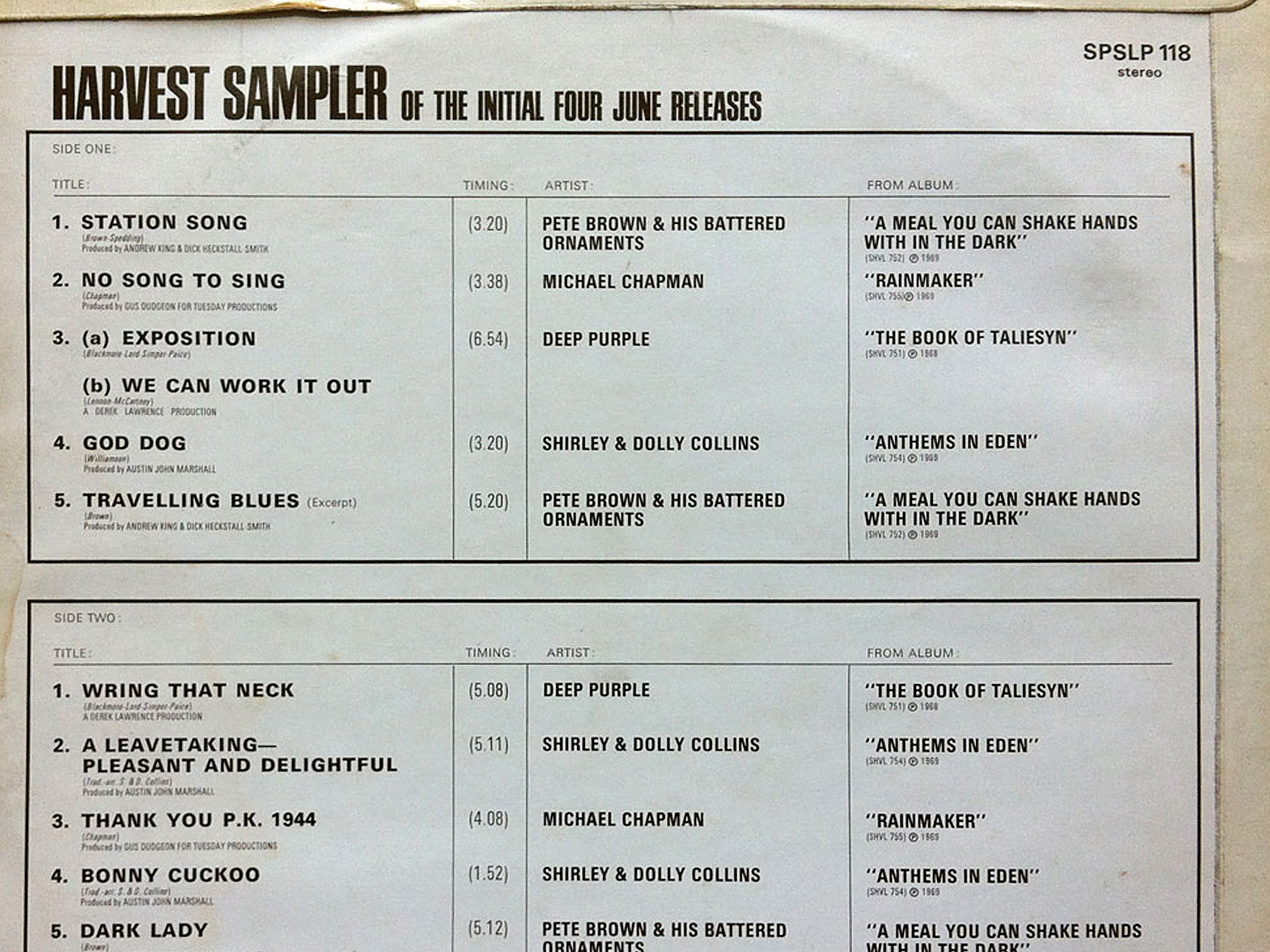

EMI launched the label in the summer of 1969 with a great fanfare: four album releases and an event at London’s Roundhouse. Supporting Deep Purple were a selection of Blackhill’s players: Broughton, Pete Brown’s Battered Ornaments, Shirley and Dolly Collins, Chapman and the early-music experimenters Third Ear Band. The launch was celebrated by the release of the snappily titled promo album Harvest Sampler Of the First Four June Releases, which had tracks from Deep Purple’s The Book of Taliesyn, Pete Brown And His Battered Ornaments’ A Meal You Can Shake Hands With In The Dark, Shirley and Dolly Collins’ Anthems In Eden and Michael Chapman’s Rainmaker.

Most of the label’s recordings were carried out at Abbey Road, the home of EMI. Pete Mew was one of Abbey Road’s many engineers, and had worked alongside Norman Smith, who produced Pink Floyd and had engineered The Beatles. Mew quickly gained a reputation for sensitivity with progressive rock. He first became aware of the new label when he was asked to work with the Edgar Broughton Band.

He worked on a great deal of the label releases, forging a relationship especially with Kevin Ayers. “You always knew it was going to be something interesting when we were working with Harvest,” Mew says today. “Out of the mainstream, sometimes wacky, and you would be working until the early hours – not for the faint-hearted.” Harvest’s repertoire would be overseen at various times by a who’s who of UK studio engineering and production from Mew to John Leckie, Chris Thomas, Alan Parsons to name but a few.

Within a few months, the label was enjoying its first Top 10 success with the release of Pink Floyd’s fourth album, the part-studio, part-live Ummagumma. It was clear, with its predominance of beautifully designed and skinning-up-friendly gatefold sleeves (the fabled SHVL series) that packaging and design would be central to the label moving forward. Designers such as Hipgnosis and (less frequently) Roger Dean were commissioned.

Later label head Mark Rye recalled in 2014 that Harvest had its own identity and was kept separate in EMI’s venerated Manchester Square headquarters: “The Harvest office was just this dark corner, as far away from everyone else as you [could] get,” he said. “And it had cushions on the floor rather than desks and chairs. It was very much a distinct part of EMI.”

**THE GOLDEN PERIOD: **

Alhough the label had many big hits after its first five years, this was when it truly was firing on all cylinders, recording the most eclectic mix of artists. In 1970, just before Malcolm Jones left, he said that he felt by the end of the year, “75 per cent of the album charts will be progressive music and, secondly, by virtue of the greater popularity of this kind of music, the ‘progressive’ tag will have been dropped and that what is still regarded by some as a minority taste will have become just another aspect of pop music.”

Aside from his production work for Syd Barrett, and a period at Polydor, little is known about Jones. “He was just a nice, quiet chap,” Mew recalls.

The label enjoyed the breakthrough success of Deep Purple, seeing them truly find their style with In Rock, which then grew with Fireball the following year. 1973 was arguably the greatest year in Harvest’s existence with strong singles chart successes with the commercial retro of Roy Wood’s Wizzard, and the phenomenon that became_ The Dark Side Of The Moon_. The release of Pink Floyd’s eighth studio album in March 1973 truly created an ‘us and them’ at the label. Floyd went stratospheric, but many of the original roster had either moved on, burnt out or disbanded. Jenner, King and Malcolm Jones had left. Deep Purple departed in 1972 to form Purple Records, while soon ELO, Roy Wood, Kevin Ayers and Barclay James Harvest all left for other labels.

**WHAT HAPPENED NEXT: **

Harvest continued, with each new Pink Floyd album increasingly becoming an industry event. The rest of its catalogue was diversifying – with only Floyd and Harper left from its original signings, groups for the era of Bowie and Roxy and Queen came along, such as the much-loved Be-Bop Deluxe and the frankly forgotten Sadistic Mika Band. But by now, the label’s image was changing, becoming increasingly unsure whom it was representing.

Thanks to Nick Mobbs’ progressive A&R policy, in early 1977 Harvest seemed ahead of the game, releasing the live punk compilation The Roxy London WC2 in July. After that January’s Animals from Pink Floyd, the label presented two sides of the same coin: a postcard from a chilly, changing London. The new wave connection continued with the signing of Australian punks The Saints, and in one of the acts from the Roxy album, Wire, they had another art-rock group, who instead of being lumped in with prog, were now lumped in with punk. In fact, Mobbs had signed the Sex Pistols to EMI. They declined the offer to be on Harvest, denouncing its roster as “hippie shit”.

However, there was something of a lack of direction. At the same time as Soft Machine were releasing their final works on the label, French disco group La Belle Epoque were enjoying a Top 3 hit with their cover of Black Is Black and Marshall Hain’s seminal soft-rock Dancing In the City showed an imprint suffering something of an identity crisis. It was, by now, fundamentally just another record label.

By the mid-80s, aside from success with the Scorpions and Pallas, Harvest was the home of the acrimoniously resting Pink Floyd solo releases and a clearing house for EMI reissues via the Harvest Heritage imprint, which had launched in 1974 with the double-pack of Floyd’s first two Columbia albums – The Piper At The Gates Of Dawn and A Saucerful Of Secrets – as A Nice Pair. A coupling of Syd Barrett’s two Harvest albums followed, and then, a series of releases looking at the label’s past, as well as releases by other EMI heritage acts. It was overseen by A&R man Colin Miles, who would later launch – with Harvest label manager Mark Rye – See For Miles, one of the UK’s first reissue labels. Aside from reissues, Harvest lay dormant.

In 2006, Nigel Reeve, then A&R at EMI and something of a catalogue visionary, revived the imprint. By the time he joined EMI in 1986, “Harvest was not a going concern as a label and it was being used for original and re-releases of Harvest artist repertoire,” Reeve says. “I relaunched Harvest with two albums by The Blue Aeroplanes, and an album and single by Patrick Duff, the former lead singer with Strangelove. There was also a compilation/sampler that included the new and old Harvest artists.”

Syd Arthur: the new blood of Harvest Records.

**TODAY: **

The Harvest imprint has been brought back to life and is run out of the US as an offshoot of the Capitol label (now part of the Universal Music Group). Among their signings are Charlotte OC, Banks, TV On The Radio and Syd Arthur (and briefly, Morrissey). With their insistent, art-influenced prog-pop, they show that the label has in some respects not travelled far at all from its original intent. With some irony, the catalogue it once released has moved to Warner Brothers who, if the product is altered and extra tracks are added, reissue it on the – wait for it – Parlophone label. It all goes full circle.

**WHY WE SHOULD CARE: **

Harvest showed that the majors could ‘get with it’, providing that the suits kept well out of the way. It nurtured and encouraged Pink Floyd to record their greatest material. “I always considered it as a label that had no boundaries musically and that it should not historically be seen as a progressive rock label, even though there was much prog rock on it!” Nigel Reeve says today. “However, if having no boundaries and allowing artistic freedom is progressive, by its nature then Harvest was a progressive label.” Pete Mew adds, “I still think the concept of having a label for breaking new acts, with new ideas, is great. Perhaps if we had one now, modern music wouldn’t be so undifferentiated.”

Harvest Facts:

The details behind the label.

First UK No.1 Single:

See My Baby Jive – Wizzard (May 1973)

Amount of UK No.1 singles: Three

Biggest selling single: _Another Brick In The _

_Wall (Part II) – Pink Floyd 1.08 million in the UK, _

1.5 million in the US

First No.1 album: Atom Heart Mother – Pink Floyd (Oct 1970)

Last No.1 album (to date): _The Final Cut – Pink Floyd _

(March 1983)

**Why the distinctive catalogue numbers? **

The SHVL number signified a deluxe single album with a double wallet. The SHSP was a single album in a single sleeve. SHDW applied to double albums. SHTC was a triple cover. Former EMI executive Michael Heatley suggests what each possibly stood for: SHSP (Stereo Harvest Standard Package (or Price); SHVL (Stereo Harvest Very Luxurious); SHDW (Stereo Harvest Double Wallet); SHTC (Stereo Harvest Triple Cover).

Further Listening Expand your mind with these Harvest gems…

A Breath Of Fresh Air:

A Harvest Records Anthology 1969-1974

_(2007) _

Compiled by Mark Powell, this three-disc overview of Harvest’s golden years updates the tradition of the label’s fabled samplers, 1970’s Picnic – A Breath Of Fresh Air and the following year’s A Harvest Bag. Your adventures with the Harvest label should start here.

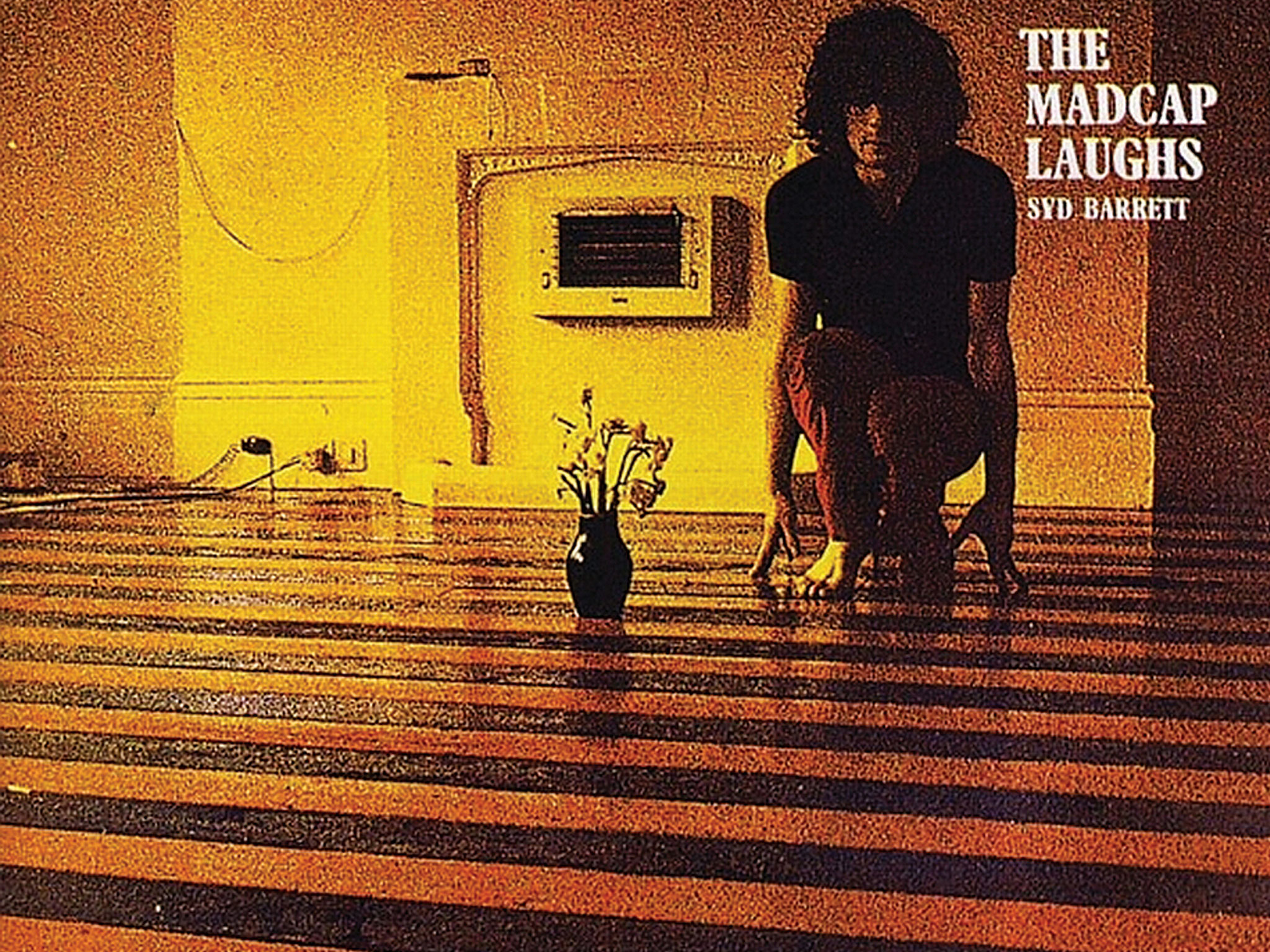

Terrapin

**Syd Barrett **

(from The Madcap Laughs, 1970)

The recordings on his two Harvest albums are, in turn, mercurial, ramshackle and damaged. But thank heavens we have them. “When I worked with Syd, he was not at his most together,” Pete Mew says.

Taking Some Time On

**Barclay James Harvest **

(from Barclay James Harvest, 1970)

Although they were to become (in their own words, of course) a “poor man’s Moody Blues”, the early albums of Barclay James Harvest make some case for having flashes of prog northern soul, none more so than on this splendid single from their debut album in 1970. They were clearly very different to the acts on Harvest such as the Edgar Broughton Band. “We were playing a different type of progressive music,’ John Lees recalled in 2006. “We were more symphonic and they were kind of… wazzawazza.”

The Lady Rachel

**Kevin Ayers **

(from Joy Of A Toy, 1969)

“Kevin always knew in his head what he wanted, but it sometimes took a while to communicate it,” Pete Mew says about Ayers. “For example, he wanted The Lady Rachel to be ‘dark, but not dull’. You try and translate that into sound. A very talented guy.”

**There’s No Vibrations, **

But Wait!

**Edgar Broughton Band **

(from Sing Brother Sing, 1970)

“The Edgar Broughton Band were proto-punks,” Peter Jenner said in 1989. “A lot of their actions were very punk, very much a band for the people, stirring them up, getting them motivated, free concerts in places like Brighton and Redcar, getting arrested. Not middle-class boys like the Floyd or trendy happening-round-London like Bolan.”

“I always liked the Broughtons,” Mew adds. “The overtime from working with them bought my first house.”

Garden Of Time

**Syd Arthur **

(from Sound Mirror, 2014)

From the reborn Harvest Records, this new Canterbury sound from this young band has been approved by Paul Weller, and captures the heady swirl and possibility where prog meets pop. Well worth seeking out.

Daryl Easlea has contributed to Prog since its first edition, and has written cover features on Pink Floyd, Genesis, Kate Bush, Peter Gabriel and Gentle Giant. After 20 years in music retail, when Daryl worked full-time at Record Collector, his broad tastes and knowledge led to him being deemed a ‘generalist.’ DJ, compere, and consultant to record companies, his books explore prog, populist African-American music and pop eccentrics. Currently writing Whatever Happened To Slade?, Daryl broadcasts Easlea Like A Sunday Morning on Ship Full Of Bombs, can be seen on Channel 5 talking about pop and hosts the M Means Music podcast.