“I was ready to go out and really promote the album. But then Guns started to stir and the plug was pulled”: The ‘back-to-basics’ side-project that saw Slash step out of the shadow of Guns N’ Roses – and led to his departure from the band

Way before Velvet Revolver, Slash’s Snakepit were the GN’R guitarist’s first extra-curricular band

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

Already an iconic figure, with one of the most recognisable images and guitar styles around, Slash stepped out of the vast shadow of Guns N’ Roses to become leader of his own band – and master of his own destiny – with Slash’s Snakepit.

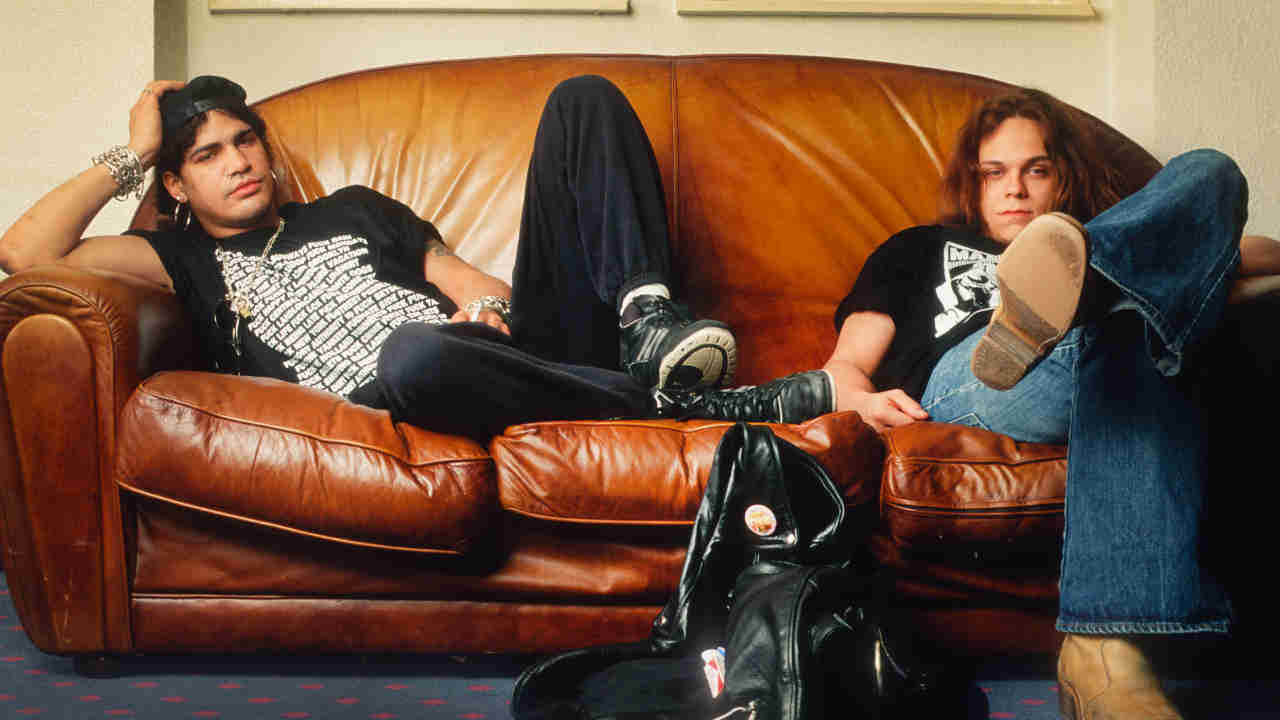

It began in 1994 when he started jamming with GN’R drummer Matt Sorum on a series of back-to-basics songs that would form the basis for what would be the Snakepit’s debut album, 1995’s It’s Five O’Cclock Somewhere, although at that point, Slash saw the whole thing as no more than a way of filling in time before Guns N’ Roses went back into action.

“This isn’t some sort of solo project,” he explained at the time. “Really, what we’re doing is getting song ideas together. They’ll probably all end up on the next Guns album anyway. So, talk about me going solo is totally off the mark.”

However, as things began to develop it appeared obvious that what Slash was doing belonged in its own setting. In came GN’R rhythm guitarist Gilby Clarke, Alice In Chains’ bassist Mike Inez and vocalist Eric Dover, previously guitarist with cult power-pop band Jellyfish.

“Eric’s amazing,” said Slash in 1995. “He’s got the voice I’ve been looking for to complete the band. You know, getting the right guy out front gives the whole thing some sense.”

Slash wanted to call the band just Snakepit – the guitarist was famous for his collection of snakes, but his label, Geffen, insisted on adding his name for marketing purposes.

Released in February 1995, three-and-a-half years after GN’R’s two Use Your Illusion albums (at the time their most recent collection of original material), It’s Five O’Clock Somewhere didn’t sound like it was a collection of songs that were just lying around unused.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

On the contrary, they were bright, powerful, full-on rock’n’roll excursions. These suited Slash’s temperament, each track having a life-force and personality of its own, yet fitting neatly into an overall pattern. Just as the band had come together through a series of jams, so the album’s sound bore that same spontaneity. It was far removed from where GN’R were located, yet so in tune with how the band had sounded in their more exciting, formative days.

What’s more, the record actually gave Slash his own audience. Not one predicated on Guns N’ Roses hysteria, but one that could appreciate who he was and what he was trying to do. A major tour was in the offing, but in the end this was severely curtailed.

“I was ready to go out and really promote the shit out of the album,” Slash said a few years ago. “I was led to believe that Geffen would back me. But then Guns started to stir, and the label decided that had to be the priority, so the plug was pulled.”

At the time, Slash accepted this situation, because he was still seeing Snakepit as nothing more than an occasional piece of fun, something to do while he waited for further GN’R activity.

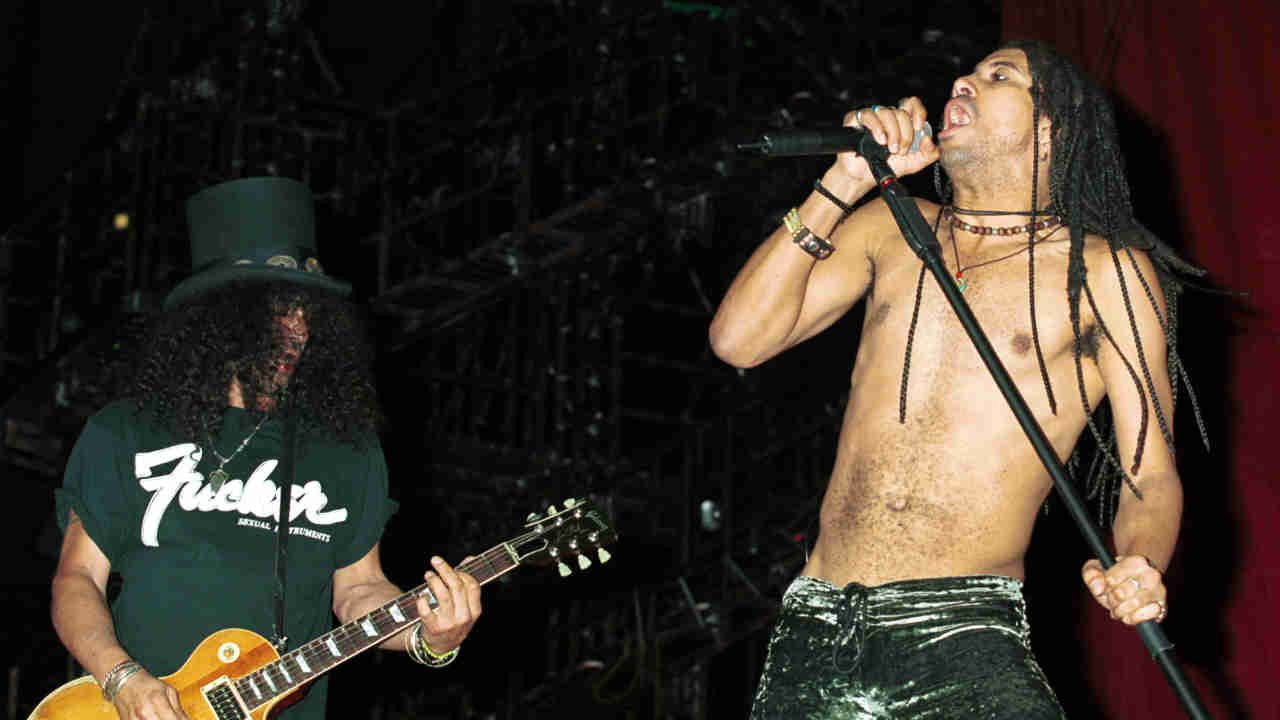

However, in 1996 Slash finally went his own way, leaving the GN’R camp behind, and resurrecting his Snakepit. This time it was no heel-kicker, but a genuinely forward-thinking, self-contained entity.

The revamped band came with a totally different line-up and mentality. Slash brought in vocalist Rod Jackson, guitarist Ryan Roxie, bassist Johnny Griparic and drummer Matt Laug for the 2000 album Ain’t Life Grand, with veteran producer Jack Douglas also coming onboard (the debut had been produced by GN’R man Mike Clink).

The result was a sharper, more focussed recording. Not that Slash and his new band had lost any of the joie de vivre that was so identifiable on the debut, but this time there was a more rigorous sense of dynamic.

With a new label, Koch, behind him, Slash was able to take Ain’t Life Grand on the road. One of the highlights on this tour was getting the chance to open for AC/DC on a few dates. There was also a major burst of club dates, with the smaller venues suiting the band far better. Here they had their own audience, packed in, with an electric atmosphere.

Sadly, the band was never able to develop any further. Slash was hospitalized, suffering from cardiomyopathy – years of drinking had taken their toll, and he needed urgent treatment to prevent the swelling of his heart. When he was discharged, the guitarist decided to end Slash’s Snakepit and move on. But this was an important step in his development, not only as a musician, but also as a more rounded person.

“With Guns N’ Roses you took a lot for granted,” he said in 2002. “There were just so many people there to look after every aspect of your life. All I had to do was get onstage or into the studio and play guitar. That was it. But when I started Slash’s Snakepit, I didn’t have all that back-up. I had to do things for myself and learn how to deal with other members of the band as a leader, not just as a musician. It was a learning curve.”

It’s easy for people to dismiss the Snakepit-era as just the stop-gap between Guns N’ Roses and his next big supergroup Velvet Revolver. In reality, though, this was a crucial bridge between these two major bands. These two albums were not only very impressive in their own right, but you can hear how Slash used the freedom he enjoyed to move his presentation and performance forward.

There’s a confidence about Slash here that tells of a musician growing and maturing. It was as if the six-string gunslinger we heard on Appetite For Destruction in 1987 was at last finding his own worth and fulfillment. While the man can play in any style he wants, Slash’s Snakepit allowed him to learn more about his own abilities and where he wanted to take them.

“Man, I love those albums,” said Slash in 2002. And with good reason.

Originally published in Classic Rock Presents Slash

Malcolm Dome had an illustrious and celebrated career which stretched back to working for Record Mirror magazine in the late 70s and Metal Fury in the early 80s before joining Kerrang! at its launch in 1981. His first book, Encyclopedia Metallica, published in 1981, may have been the inspiration for the name of a certain band formed that same year. Dome is also credited with inventing the term "thrash metal" while writing about the Anthrax song Metal Thrashing Mad in 1984. With the launch of Classic Rock magazine in 1998 he became involved with that title, sister magazine Metal Hammer, and was a contributor to Prog magazine since its inception in 2009. He died in 2021.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.