"I'll break both yer arms": Memories of life with Lemmy as a friend and neighbour

Classic Rock writer, former Zigzag editor and Motörhead biographer Kris Needs was also Lemmy’s neighbour in London’s Notting Hill

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

More than 45 years ago, after a hard day editing Zigzag magazine at its offices off Portobello Road it became something of a routine to visit Lemmy at his home around the corner. Essentially a low-lit basement, his lair boasted a double bed, comfy chairs, floor cushions, stereo system, and a patchwork-mirrored coffee table that had obviously seen action.

Walls were hung with Motörhead-related flags and posters, shelves and cupboards stuffed with books, records and identical white boots. Lemmy stayed here all the way through Motörhead’s rise to No Sleep ’Til Hammersmith. “I like it here!” he explained. “It’s a nice, shabby pit for me to crawl into. I’ve always lived like this.”

Lemmy at home was somewhat different from the Lemmy in public; the perfect host playing his beloved early rock’n’roll 45s, pouring large vodkas, splintering the speed mountain, or simply expounding on various subjects to his audience of one. His dry delivery, somewhat reminiscent of Les Dawson, made for killer one-liners.

Our uproarious liaisons started after Zigzag – the first serious UK music monthly, which I’d turned into a punk mag – gave Motörhead’s self-titled debut single then first album rave reviews when they were still the most ostracised band in Britain (bar diehards).

Our first meeting was in the dressing room after the band had just demolished my local Friars club, in Aylesbury, in August 1977. Lemmy greeted me with his traditional initiation ritual, thrusting forth a dagger piled with speed and commanding: “Do it till it hurts!” followed by downing a can of Special Brew in one.

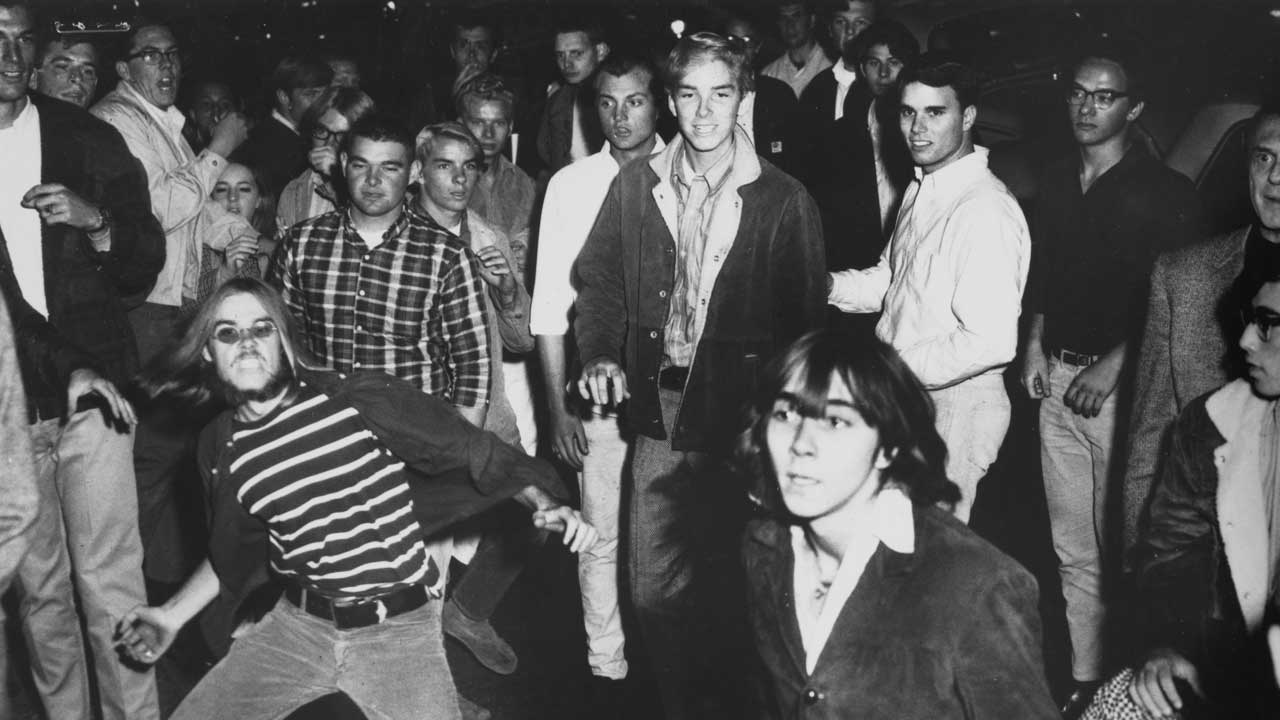

After Zigzag gave Motörhead a four-page feature, it went from there, including taking him to Soho punk niterie the Vortex, where the punters parted like the Red Sea when he walked in. Soon he was chatting to The Clash, Billy Idol and Gaye Advert. Despite his long hair, flared jeans and cowboy boots, Lem commanded respect as a fellow outlaw who made more noise, took more drugs and didn’t give a fuck more than anybody in the room.

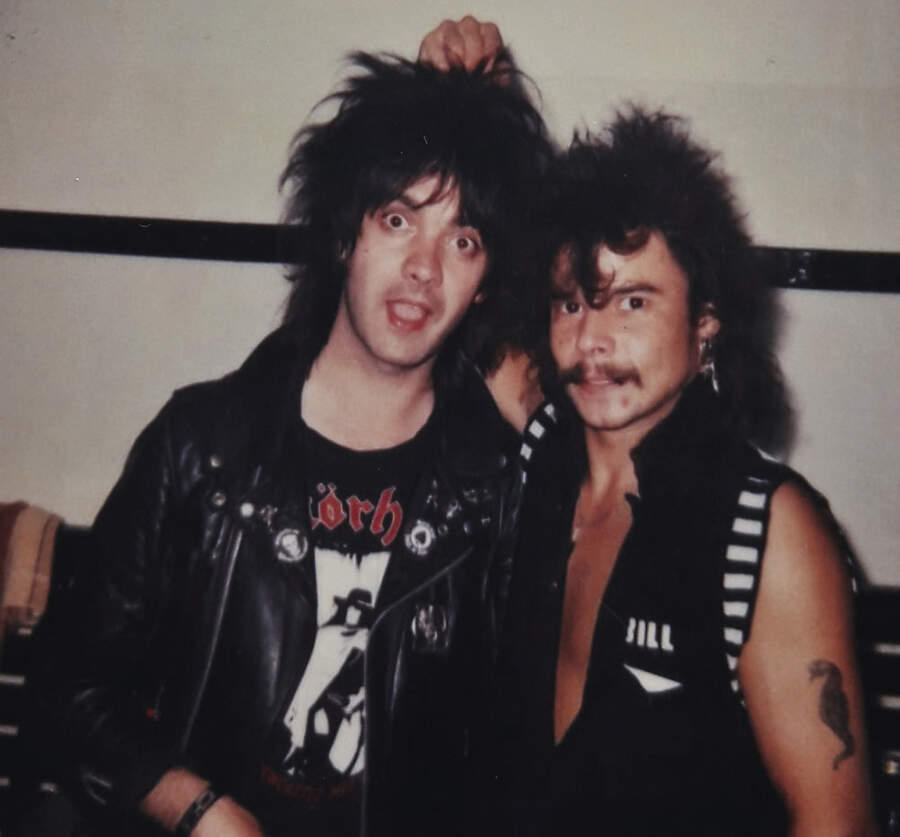

While the punk crossover showed how easily Lem could move in any arena he was thrown into, Motörhead were still up against an elitist music press. In early ’78, Blondie also faced such hostility. Then after Denis became a hit they headlined the Roundhouse that March. As Blondie’s first UK press champion, I mentioned to Lem that I was going to the gig. He really wanted to meet Debbie Harry, so I took him to the dressing room and introductions were made. Of course he fancied her, like every other male in the country. But in many ways Lemmy was an old-fashioned gentleman, and simply turned on the charm. Debbie and her partner, Blondie guitarist Chris Stein, loved him.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Only after Motörhead signed to Bronze Records did Lemmy know his band were safe from splitting. One night in December ’78, he marched into London club Dingwall’s, grabbed me by the arm and insisted I accompany him to Bronze’s nearby studio to hear a new song called Overkill that Motörhead had just recorded. Right from Philthy’s double kick drum entry, we both knew Motörhead’s future was now assured.

As the band’s star rose through ’79, Lem decided I should write Motörhead’s biography. It was exhilarating and satisfying to witness his and the band’s change of fortune from close quarters. The main change in Lemmy was some relief that the precarious hustles could stop. I was struck by his close interest in the first book written about him and his band, going through the manuscript and correcting it in biro, like making sure his Angels mate Tramp’s lyrics for Iron Horse were in the right order.

Overkill lighting the touch-paper for Motörhead’s success allowed the colossal bomber stage prop that clinched it. Predictably beset by mishaps, Lemmy never took himself or the increasingly elaborate stage props too seriously, guffawing when they went wrong.

At 1980’s triumphant Heavy Metal Barndance in Stafford’s Bingley Hall, he struck a pose on the lowered bomber and got stuck as it rose upwards. The Iron Fist tour’s stage-on-chains and rather ridiculous fist (once clenching with Lem inside) drew his derision. But the parachutists who missed Port Vale football ground during the Heavy Metal Holocaust and landed in a nearby allotment remained his favourite.

When Motörhead started recording Ace Of Spades at Jackson’s studio, just up the line from Aylesbury, I was able to watch its creation from start to finish. One evening, Lemmy adjourned to the gents, and 10 minutes later returned, smiling, with the words he’d just written for Ace Of Spades. He relished writing some lyrics: “I start with a typical Motörhead title, like Love Me Like A Reptile, sitting there in hysterical laughter writing these ridiculous words!”

From my five years spent in Motörhead’s close orbit (before splits and flops added the world-weary element) there are too many priceless memories to include here. The most resonant include the Midnight Sun Festival in Finland where we decided to give the buckling dressing room caravan a flaming Viking burial on a lake; the Christmas 1980 Zigzag photo session when I hired three Santa outfits from Berman & Nathans, and the photo ended up adorning the Ace Of Spades single (after the beards became quiffs and sporrans I lost my deposit); waking up in the hotel bar after Port Vale, with a shrimp net on my head and a smouldering cigarette in my ear; accompanying Lem back to London, I was oblivious to ‘BOLLOCKS’ that he’d written on my forehead in black felt tip.

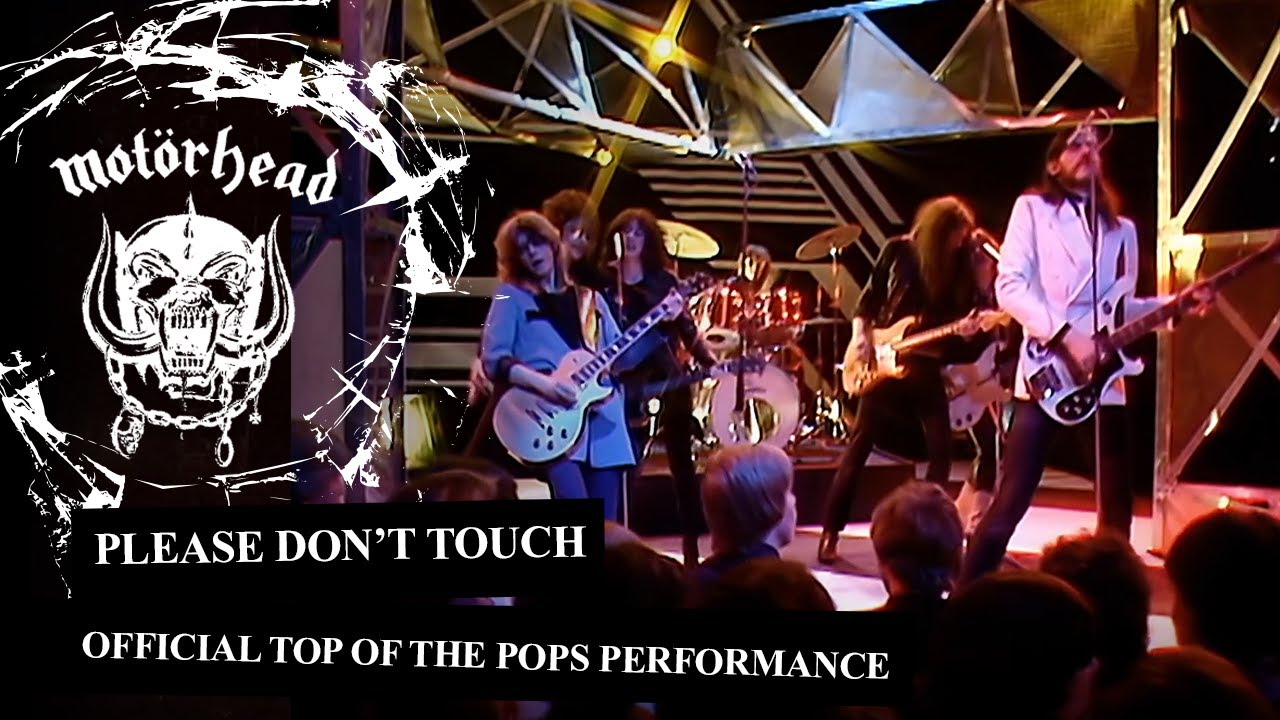

There were five Top Of The Pops appearances, including The St Valentine’s Day Massacre with Girlschool revealing his eternal love for their guitarist Kelly Johnson. On a more serious note, Lem once informed me that if he caught me taking heroin, "I’ll break both yer arms".

Our last interview, in 1990, was after he’d moved to LA. I now treasure these memories before Lem became embedded in his chosen fate, living out my favourite quote from him from that time: "This is like a vocation. I love rock’n’roll. It’s my life. It’s a complete thing, twenty-four hours a day. I’m Lemmy out of Motörhead. That’s what I do. That’s what I am."

Kris Needs is a British journalist and author, known for writings on music from the 1970s onwards. Previously secretary of the Mott The Hoople fan club, he became editor of ZigZag in 1977 and has written biographies of stars including Primal Scream, Joe Strummer and Keith Richards. He's also written for MOJO, Record Collector, Classic Rock, Prog, Electronic Sound, Vive Le Rock and Shindig!

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.