Donovan: my stories of The Beatles, Marc Bolan, Jimi Hendrix and more

Brian Jones got him his first big break, he meditates with David Lynch, and he mislaid Jeff Beck's guitar. He's the first star of British folk music, Donovan

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

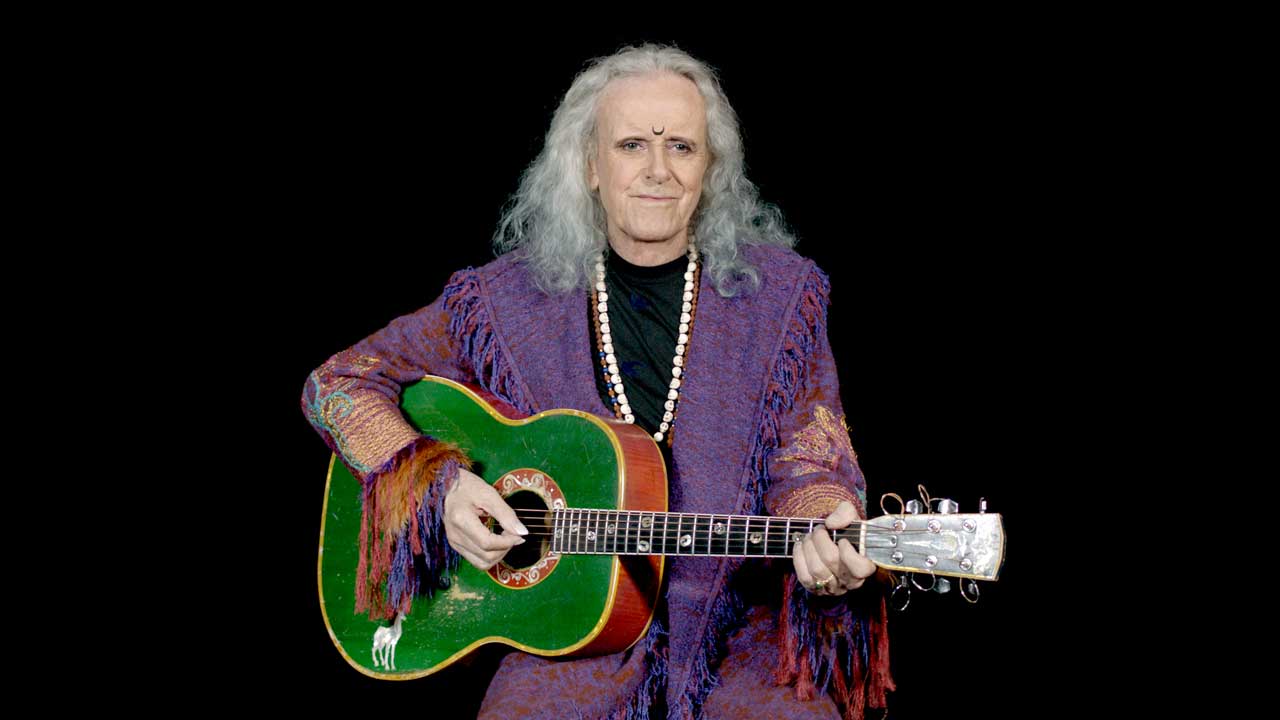

The first British folk singer to crack the UK pop charts, Donovan (Phillips Leitch) made the Top 5 with his first single, Catch The Wind, early in 1965. By the end of that year the ‘British Bob Dylan’ had scored two more hit singles, two hit albums and a hit EP.

As flower-power blossomed, so did Donovan as songs like Mellow Yellow, Hurdy Gurdy Man and Barabajagal soaked up rock and jazz embellishments. He stepped off the merry-go-round in the early 70s before it turned into a treadmill, and recorded and toured intermittently.

After the Happy Mondays sponsored his revival in the early 90s with a track on their Pills ’N’ Thrills & Bellyaches album, Donovan recorded Sutras with producer Rick Rubin in 1994, an album that took more than a decade to be fully appreciated. His most recent album, 2021's Lunarian, featured ten songs dedicated to Linda Lawrence, his wife of more than 50 years, and the inspiration for 1966's trans-Atlantic hit Sunshine Superman.

The Beatles

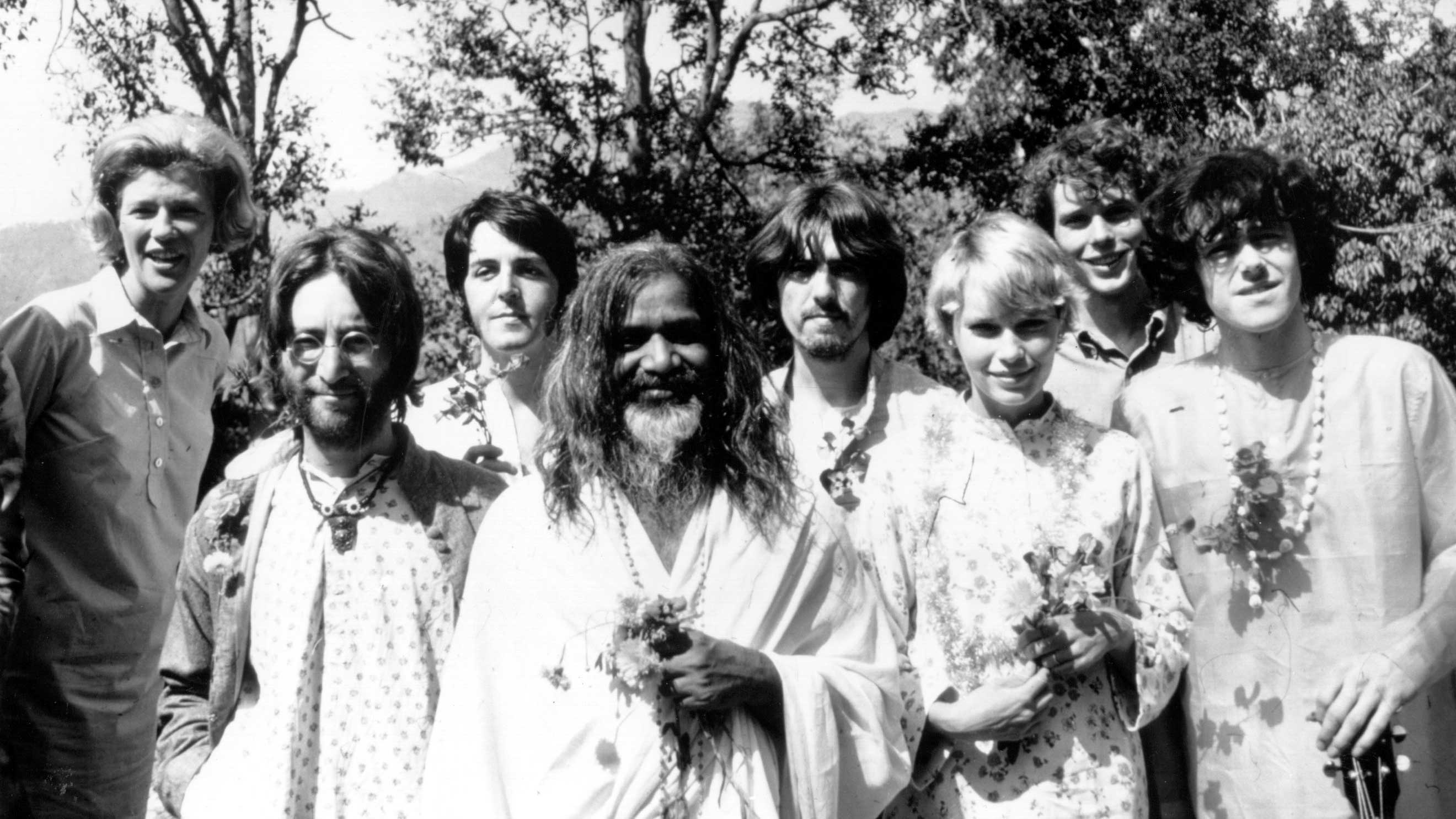

Martin Lewishon, the legendary Beatles biographer, told me: “You don’t know this, Don, but you had more social, musical and spiritual contact with these four guys than anyone of your generation.” At the time, of course, we were young and crazy and we didn’t know how long it was going to last.

George and I were closest because of our spiritual paths and the books we were both reading. John was fascinating to be around; he didn’t suffer fools gladly. Paul was full of light and energy and jokes and we would constantly be jiving each other. We tried to write songs together but it was impossible, because every idea I had sparked him off and every idea he had sparked me off.

But the real deal happened in India. George said later that you can hear me all over The White Album. We only had the acoustic guitars, and that’s when we really got to know each other.

Brian Jones

One day in 1964 Brian Jones walked into a basement studio in Denmark Street. He had heard about this new kid on the block. He came in and saw what I was doing. He had a word with Elkan Allen at [TV pop show] Ready Steady Go. I went on for three weeks – completely live, no pre-recording. And that set me up. Afterwards I met a girl, Linda Lawrence, who would become my muse and wife. She’d had a child with Brian. I didn’t even know this when I met her. There was a very interesting karmic triangle going on.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Bob Dylan

It wasn’t like you see in the Don’t Look Back film. We had met before, briefly. Folk met rock when Dylan, Joan Baez and myself were together that May in 1965. I’d already had a hit with Catch The Wind, and Bob and Joan, who were both album artists, released singles – Joan had There But For Fortune and Dylan’s was The Times They Are A Changing. It was clear that Bob was going to go electric and I was going to go electric folk jazz. It was also clear what we were going to do with it, too, because a few days later Bob introduced me to The Beatles.

Marc Bolan

Marc asked if he could open for me when I played the Royal Albert Hall. That was with T. Rex and they sat crossed-legged on the floor, much like me. But sleeping inside Marc Bolan was a little rock’n’roll guy. We met again on his rise to fame in a funky little flat near Marble Arch. He’d brought two little metal dinosaur toys back from Tokyo and said: “Do you want a battle?”’ We got these two tin T. Rex’s going at each other, and they made all the roaring sounds and out of their mouths came little puffs of talcum powder.

I made a recording with him in Munich about a year before he died, a rock version of Lalena, but it’s lost. I asked his son Roland if it had been found but there’s no sign of it.

Mickie Most

Mickie Most was the Phil Spector of Britain. He was very experimental. We were introduced by Allen Klein as part of a deal.

Allen said: “Here’s your producer.” Mickie said: “I’ll pick the singles and you do what you want on the albums.” And that opened a whole world for me.

The studio became a bohemian painter’s studio for me. And Mickie would say: “I’ll have that one” – Mellow Yellow, Sunshine Superman, Hurdy Gurdy Man. I didn’t know whether they were popular songs or not; Mickie knew. And he had this instinctive sense: “Take that out, put that in.” And it worked. I wish he was still here. I’d like to make another record with him.

John Paul Jones

Our initial meeting was a little strained. He’d come in to arrange Mellow Yellow and it had this great New Orleans thump to it. But when I listened to the playback something sounded wrong. I didn’t know what it was. So I’m frowning, and John is glaring at me because he thought he’d done something wrong. I said: “No, it’s just that there’s something… not mellow.”

And Mickie Most is going: “Well for fuck’s sake find out what it is.” And then one of the horn players says: “I know what Don means. We gotta put the hats on.” And Mickie goes: “For Christ’s sake, what’s an ’at?” And the main horn player says: “The mutes, Mickie, the mutes.” So they did it again with the mutes and everyone went: “Wow.” Now it was mellow.

Jimi Hendrix

I saw him at [London club] the Bag O’Nails. Everyone was there: the Stones, The Beatles, The Who, The Kinks. Chas [Chandler, Hendrix’s manager] had invited everyone. He’d put this thing together. He told me: “I’ve got a jazz drummer and a bass player who’s a guitar player.” And it was quite incredible. Such a superb blend of musicians.

I didn’t see him much after that because we all went on the road and we all got famous and our paths only crossed occasionally. But when I wrote Hurdy Gurdy Man I thought of Jimi. I said to Mickie Most: “This is for Hendrix.” And he said: “No it isn’t, it’s for you.”So I said: “Let’s get Hendrix to play on it.” Mickie phoned Chas who said: “Jimi’s playing shows back-to-back.” So we got Jimmy Page. And aren’t we happy about that. Because what came out of that, thanks to Jimmy, Mickie Most and John Paul Jones, was something that was pagan Celtic rock’n’roll, not a copy of American rock’n’roll.

Jeff Beck

When Mickie Most first heard Barabajagal he couldn’t make head nor tail of it. He was working on [Jeff Beck’s album] Beck-Ola at the time and suggested that he bring the band in to see what they could do. So one morning the band troop in, except for Jeff, and I played them the chords. Eventually Jeff ambles in, sits down and doesn’t say a word. Mickie Most says: “Okay Jeff, get your guitar out.”

Jeff looks around and says: “Where is it?” The roadies had dropped off the other instruments but not Jeff’s guitar. It was locked up in a van in Manchester. Jeff says: “I suppose we could rent one.” So the call went out: Jeff Beck needs a great Fender Stratocaster. One showed up and we did the session.

Rick Rubin

He called me up in 1994 and said: “Do you want to make a record?” And I wondered who he was. Then I found out that he was meditating, just like David Lynch and I. And when I went to his house I found that his bookshelves were full of books on spiritual paths and meditation. He is a major talent. He said very little but we made beautiful music and created the Sutras album.

It was a pivotal time in my career because I realised that I wanted to continue to make records on this level. I had kind of dropped out a little but I came back with Rick. I’d rank Rick with Mickie Most, George Martin and Phil Spector. Because he listens to the song. He knows the song is everything. He also knows what he wants, but he also wants the artist to come forward and he knows that he mustn’t get in the way.

Shaun Ryder

I was doing a gig in Manchester when my son Julian, Brian Jones’s boy, said: “There’s five guys in a van out the back and they say they’ve come to take you to the Hacienda.” I said: “I remember Manchester but I don’t remember a hacienda there. So not this time, boys.”

I got to know Shaun and his brother Paul later and when I listened to the Happy Mondays. Linda and I realised they were the Rolling Stones of the 80s. You could hear that they were going to be the ones to lead the way. And then Shaun and Paul fell in love with our two daughters. Which was rather frightening at first because we didn’t know how they would take to Manchester madness. But Linda wasn’t scared. Oriole and Shaun fell in love and fell out of love but they produced a beautiful girl called Coco.

David Lynch

David and I are both outsiders within our own art. He’s an outsider in the film world, and nobody can put their finger on what I actually do. That’s given us quite a bond, and we have teamed up to promote transcendental meditation.

This interview was originally published in Classic Rock 128.

Hugh Fielder has been writing about music for 50 years. Actually 61 if you include the essay he wrote about the Rolling Stones in exchange for taking time off school to see them at the Ipswich Gaumont in 1964. He was news editor of Sounds magazine from 1975 to 1992 and editor of Tower Records Top magazine from 1992 to 2001. Since then he has been freelance. He has interviewed the great, the good and the not so good and written books about some of them. His favourite possession is a piece of columnar basalt he brought back from Iceland.