“I loved working with bands like Opeth and Marillion. I was starting to get a name for myself. But my New Year resolution was to learn to say ‘no’”: In 2009 this notorious workaholic was trying to do less. His career suggests it didn’t go that way

After over two decades making music, his main band had recently achieved global recognition and he’d just launched his debut solo album. Did he ever really slow down?

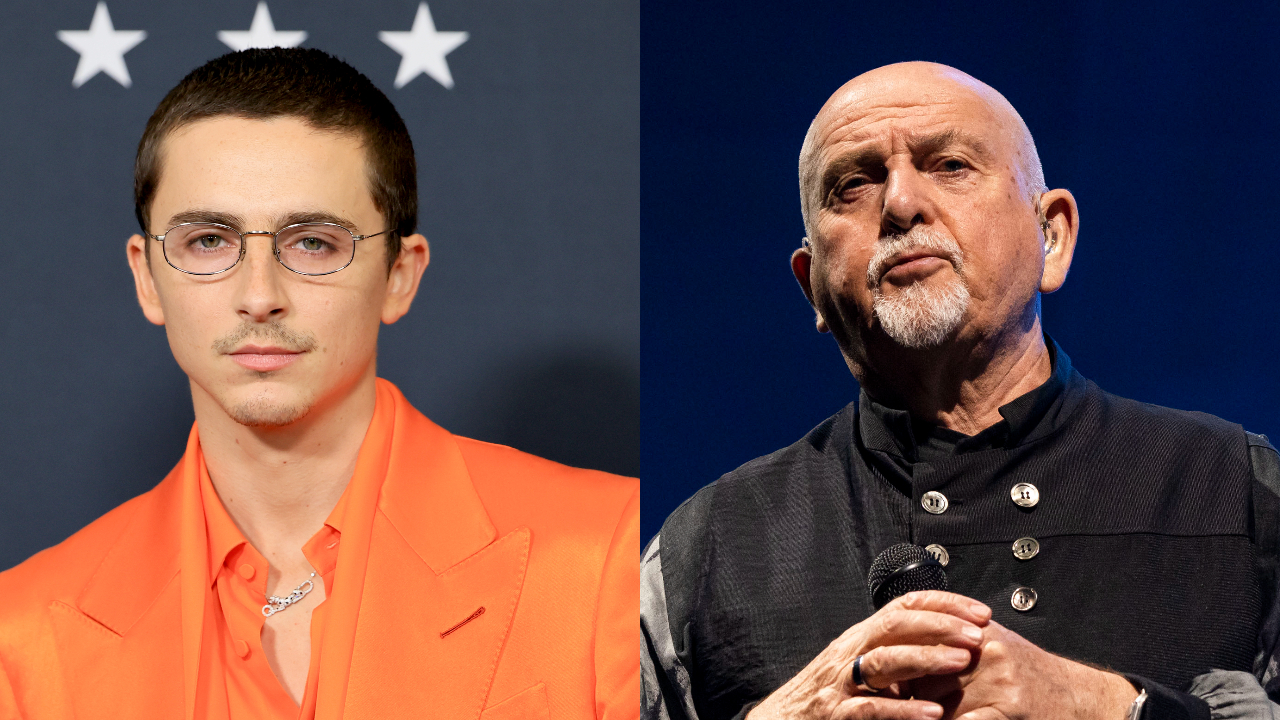

By 2009 Steven Wilson had already been leading Porcupine Tree for 22 years, and he’d developed a reputation for reinvigorating the world of prog metal and remastering prog rock classics. He’d also just released his debut solo album, Insurgentes – and as he told Prog, he was wondering if it might take him anywhere…

Steven Wilson is among the most prolific figures in the world of progressive music, his best-known groups Porcupine Tree, Blackfield and No-Man being responsible for many of the most consistently appealing – not to mention stylistically diverse – records of the past two decades. The latest of these is Insurgentes, his long-awaited debut solo release.

Strangely, for someone who became an obsessively creative singer, guitarist, songwriter and producer, the now 41-year-old Wilson doesn’t come from a musical background. In fact, based in Hemel Hempstead, Hertfordshire, and obsessed by football, a youthful Wilson rejected his parents’ overtures to learn piano and guitar.

Music nevertheless seeped into his life as he heard his dad ritually playing Pink Floyd’s The Dark Side Of The Moon as his mum elected to spin Donna Summer’s Love To Love You Baby. “The combination of art-rock and great grooves became a bedrock of my musical taste,” he suggests.

Songs by David Bowie and the Electric Light Orchestra eventually inspired him to retrieve the acoustic guitar from the attic. At 14 his electronic engineer father built him a home-made tape machine. “Before too long I was experimenting with multi-track recorders and vocoders,” says Wilson. “It helped me to learn about using the studio as a creative tool.”

Asked whether he recalls a point at which carving a career in music became something he had to do, Wilson laughs: “No, I don’t – and I’m not too sure that particular path is visible to me now.”

The young Wilson scarcely matched the stereotype of the progressive rock fan: sporting lank hair, a scruffy duffle coat and clutching a vinyl record to its collective armpit. “As a teenager I was deeply into the New Wave Of British Heavy Metal,” he says. “My jacket had Led Zeppelin and Saxon patches on the back. Progressive rock was, at that time, very much under the radar.”

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Consequently, the heavy metal act Kudos (later Paradox) was his first band of note. It wasn’t until plundering the record collection of a pal’s big brother, then attending some of Marillion and Twelfth Night’s earliest gigs, that he fell under the spell of prog. “My friend and I began to discover the subterranean world of records like The Snow Goose by Camel and the classic Hawkwind albums. It felt like we were going to see Marillion every week!”

He began to absorb various strains of avant-garde and industrial music, while developing an appreciation of industrial, experimental and ambient sounds. Porcupine Tree were formed in 1987, initially as a solo project. The arrival in 1993 of former Japan keyboard player Richard Barbieri served to vastly expand horizons.

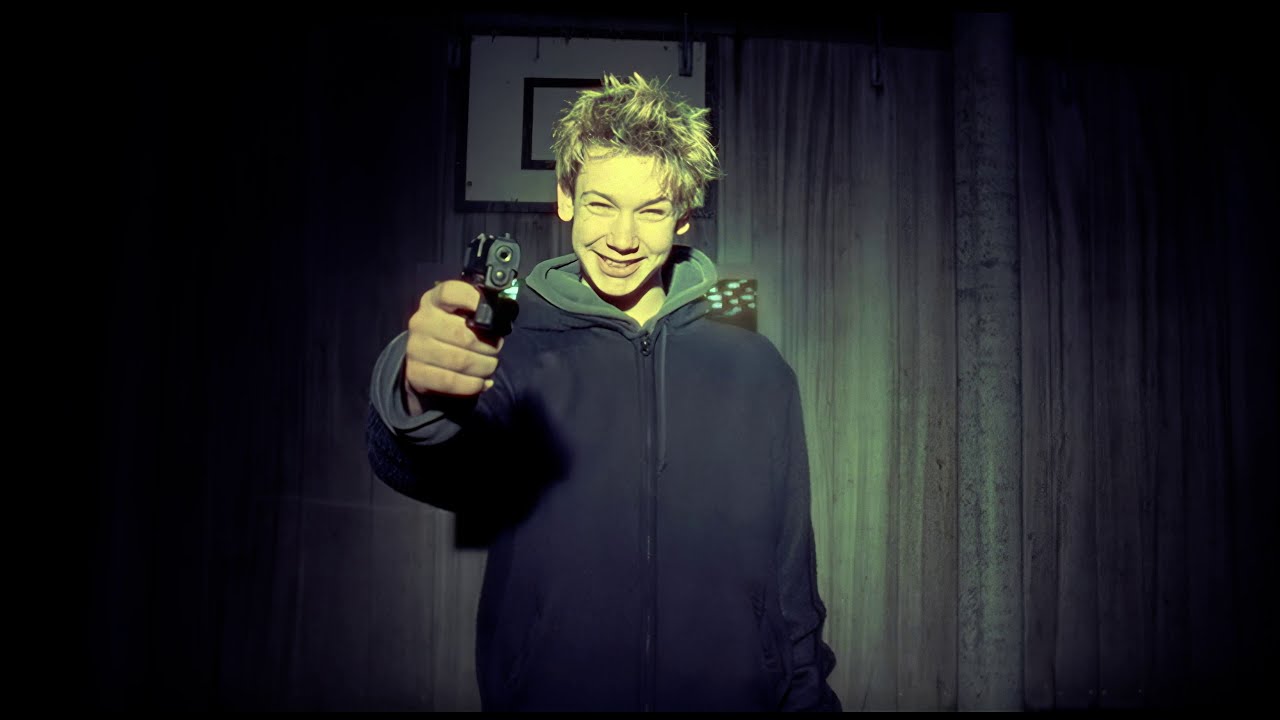

The band maintained a slow but steady arc of popularity until, six albums in, they signed to the Atlantic subsidiary Lava for 2002’s altogether heavier In Absentia, and their first taste of global regard. Wilson – who admits to a quest of “attempting to write the ultimate two-and-a-half minute pop symphony” during the late 1990s – fully appreciates the irony of achieving a true commercial breakthrough at the ninth attempt via 2007’s Grammy-nominated Fear Of A Blank Planet, a deep, dark and extremely challenging concept piece.

“I also grew up listening to things like Abba as well as King Crimson and Iron Maiden,” he says. “I’ve realised that my strength lies in writing those epic pieces. Fear Of A Blank Planet was the least commercial album we’d made for many years. It only had six tracks, and it slagged off everybody on the planet – including myself. It was as far from radio-friendly as you could get.”

And yet the record brought Porcupine Tree a rave review in Rolling Stone, an Album Of The Year gong at the Classic Rock Awards, a nomination at the Grammies for its 5.1 mix and approximately 250,000 worldwide sales – about 100,000 more than 2005’s Deadwing.

“Somebody told me recently that because CD sales have dwindled so badly, five years earlier it would have sold double that figure,” Wilson says. Happily, though, he reveals that for all his increased profile, the curse of celebrity still eludes him. “Getting recognised in the street only happens in a few places in the world,” he laughs. “Most of the time I couldn’t get arrested if I tried.”

Just before beginning work Insurgentes, Wilson speculated that it would revisit his post-punk roots, possibly with some special guests from that genre, should they like to participate. “The record does reflect my love of bands like The Cure – but I couldn’t hold back on my entire musical personality, and it ended up straying into territory that was a lot more familiar,” he explains.

I’m hardly well-known outside of rock and prog. Explaining who I am felt a bit like sending out demos as a 15-year-old

“The album’s tracks cover everything from shoegazer music to post-punk, psychedelia and jazz-rock, progressive rock and pop, to singer-songwriter ballads, even noise and drone music. That was inevitable, I suppose; all these influences are in my DNA.”

From Porcupine Tree drummer Gavin Harrison and stick bassist Tony Levin to Dream Theater keyboard wizard Jordan Rudess, Wilson’s collaborators also tended to the familiar. “I tried to get a couple of more unusual names, though not that hard,” he says. “The problem is that I’m hardly well-known outside of rock and progressive rock. Explaining who I am and what I’ve done felt a bit like sending out demos as a 15-year-old. It was a bit disheartening.”

Nevertheless, given that all 3,500 limited edition versions of Insurgentes were snapped up without any publicity and now fetch anything up to £250 on eBay, Wilson is understandably optimistic regarding its saleability.

“There seems to be a great enthusiasm for albums like mine – ambitious, arty records that are outside of generic classification,” he agrees. “Ten years ago it would have been very hard to release something like Insurgentes. I’m very gratified that my reputation ensures some people will listen and give it a chance.

“It’s an album that fans of Porcupine Tree, Blackfield and No-Man will find something in, but also – I hope – those that appreciate Muse or Radiohead, even Nine Inch Nails.”

Wilson admits that getting Insurgentes out of his system will impact upon the creative process for the Porcupine Tree project that’s about to go into production. “Making a solo record was quite liberating,” he says, “but going back to a band, there are other opinions to consider.

“Subconsciously it’s bound to affect things. The new album is not going to be conceptual lyrically, though musically it will be. We’re intending to do two discs; one will be a 55-minute piece of music, broken down into different songs. The second will have shorter, standalone pieces.”

With so many other commitments, Wilson remains uncertain whether a tour for Insurgentes is possible. “I’d love to do one, but time is an issue, also who’d be in the band. With koto players and orchestral sounds, the record is quite dense – re-creating that onstage would be quite a challenge. But it’s a subject I’m giving a great deal of thought.”

To me, anyone who takes the listener on a musical journey is prog

As somebody who grew up collecting and admiring vinyl gatefold sleeves, it’s perhaps unsurprising that Wilson ended up becoming an outspoken champion of the seven-inch single and physical records in general, as well as a critic of downloaded product.

“I’m sure my love of those old prog records was part of that – the nostalgia of saving my pocket money to go and very carefully invest in a new record, devouring the artwork and lyric sheets.

“I’m the same with movies; I won’t download one onto my computer. I want to keep the DVD. It’s about buying into an aesthetic vision, and you don’t get that with a JPEG or an MP3 file.”

Wilson’s unofficial ‘keeper of the flame’ status recently received the mother of all acknowledgements when Robert Fripp, who’s toured as a Porcupine Tree support act, allowed him to remix the King Crimson catalogue for 5.1 surround sound. “A Grammy nomination makes people take you seriously, I suppose,” Wilson says modestly.

“My manager, Andy Leff, also managed King Crimson during last year’s reunion. Like I was at first, Robert was sceptical about the idea of surround sound, but Andy persuaded him to let me have a go at Discipline. He loved it. So I’ve already done five albums, there are five more to do and they sound absolutely phenomenal.”

Wilson’s relentless productivity is such that it’s hard to imagine him ever taking a holiday. “I find it hard to switch off,” he admits. “I start to feel guilty if I have even a day or two away.” Has he wondered about this ingrained need to create music? “I probably inherited my work ethic from my father,” he replies. “Believe me, sometimes I wish was able to take things a little easier.”

Is it a source of irritation for those around him? “Of course! It drives them insane. It drives me mad too, but I can’t change. It’s why I decline offers to produce other people’s records. I loved working with bands like Opeth and Marillion and I was starting to get a little name for myself. But my New Year’s resolution was to learn to say ‘no’ more often.”

Fittingly, we close with Wilson’s observations on the current state of prog rock – or what is labelled as prog rock. “To me, anyone who takes the listener on a musical journey is prog,” he says. “I think of Massive Attack and Nine Inch Nails as prog too.

“The great thing is that people seem to be less sure than ever before of what prog actually is. When you can’t define something, what you’re referring to is pushing the envelope. And isn’t that the whole point of prog?”

Dave Ling was a co-founder of Classic Rock magazine. His words have appeared in a variety of music publications, including RAW, Kerrang!, Metal Hammer, Prog, Rock Candy, Fireworks and Sounds. Dave’s life was shaped in 1974 through the purchase of a copy of Sweet’s album ‘Sweet Fanny Adams’, along with early gig experiences from Status Quo, Rush, Iron Maiden, AC/DC, Yes and Queen. As a lifelong season ticket holder of Crystal Palace FC, he is completely incapable of uttering the word ‘Br***ton’.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.