“When the band played, we sold out to 14,000 people a night. If I play, I’m not sure 14 people will turn up”: He's fought off a crisis of confidence, but the frontman of one of prog’s greatest groups still doesn’t know who he is

Adopted soon after birth, his search for clues to his identity inspired a book which then inspired an album – and there’s a reason it’s not a completely prog work

On his latest solo album Jakko M Jakszyk has embarked on a very personal journey after a period of self-doubt. Son Of Glen is a companion piece of sorts to his acclaimed memoir on which he explores themes of identity and family bonds. He discussed “the proggiest thing” he’s ever done, and what the future might hold for King Crimson.

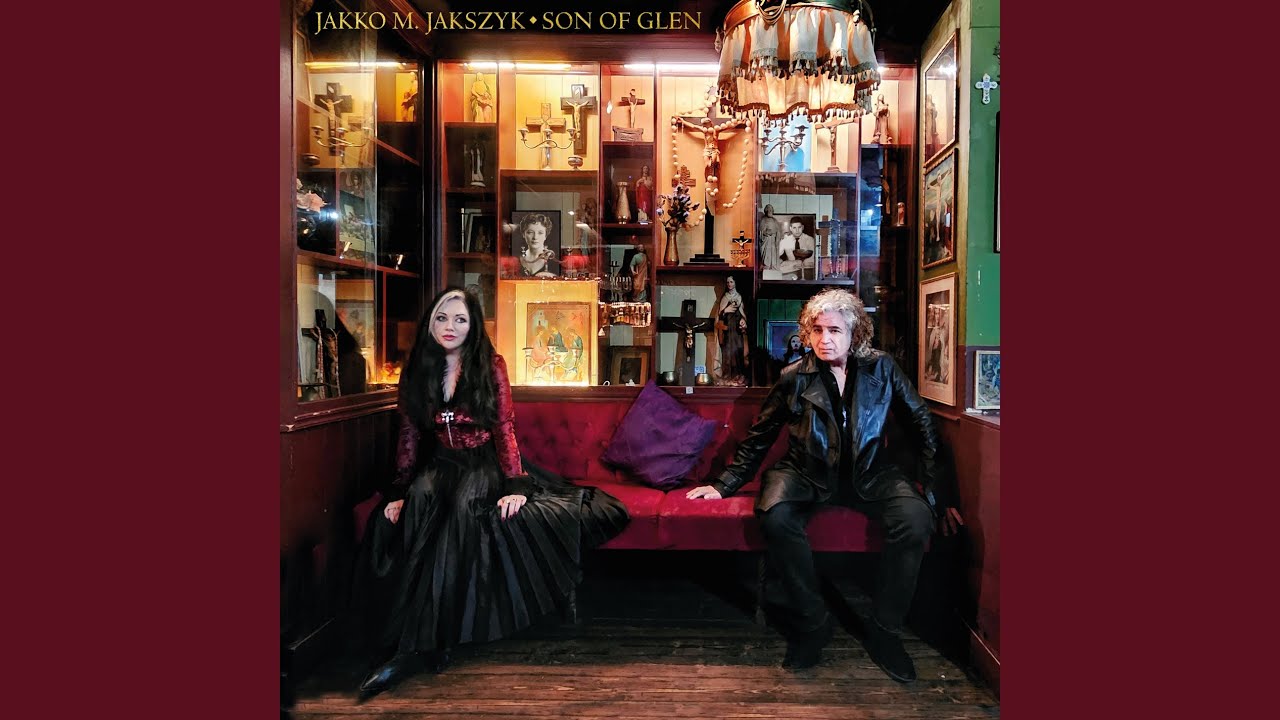

The cover of Jakko Jakszyk’s new album, Son Of Glen, is a photo of him and his sometime musical partner Louise Patricia Crane sitting at opposite ends of a plush banquette in a Belfast bar named The Spaniard.

The walls are covered in religious iconography: crucifixes, depictions of Christ, the full religious Monty. But two subtle adjustments have been made. Behind Crane, a Belfast native, is a vintage photograph of a pale-skinned, black-haired woman. Behind Jakszyk is a picture of a dark-haired man wearing a shirt and tie. Both look like they were taken in the 50s or early 60s.

The woman is Peggy Curran, Jakszyk’s biological mother, who gave him up for adoption when he was a baby. The man is Glen Tripp – the Glen referred to in the album title, and someone Jakszyk never met. “If you look closely at that photo, there’s absolutely no doubt that he’s my father,” he says. “It’s this idea of him watching me from a distance.”

Son Of Glen is the well-travelled Jakszyk’s first release since the dissolution of King Crimson, with whom he sang and played guitar during their final incarnation between 2013 and 2021. It comes a few months after his massively entertaining but deeply emotional autobiography, Who’s The Boy With The Lovely Hair?, which tells the stories of his life inside and outside music, and his attempts to track down his birth parents while processing his relationship with the couple who brought him up: his distant, Polish, WWII survivor adoptive father Norbert Jakszyk and Norbert’s French wife, Camille.

It’s basically an episode of genealogy show Who Do You Think You Are?, but with more Henry Cow. “The book came first, really,” says Jakszyk. “It did shape the album in many ways, though it’s not a concept album based around the story of my life, or anything like that.”

Son Of Glen could easily not have happened. Jakszyk admits he’d lost faith in his abilities since previous solo album, 2020’s Secrets & Lies. His label wanted another record, but the music wasn’t coming. “I had a real lack of confidence,” he says. “Or the muse had passed me. I guess there’s a degree of inertia produced by being in a band like King Crimson: ‘Who the fuck am I? Is that who I am now? Have I got to somehow put that stamp on my music?’”

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

It was Crane who galvanised him into action after Jakszyk co-produced and played guitar on her 2024 album, Netherworld. “I ended up playing a lot of varied guitar on it, things I wouldn’t play in my own music,” he says. “When you’re working on somebody else’s record and not your own, you approach it differently. And she really built me up: ‘You can do all sorts of stuff.’”

Louise came up with a fantasy, of, ‘What if your father has been guiding you?’ I don’t buy into that, but it’s nice as a narrative idea

The song that lit the creative touchpaper was his album’s shapeshifting, 10-minute title track. “It started off as this acoustic thing. Both my kids play; there are guitars all over the house. One of the kids had some mad tuning, and I started playing it ended up as this 10-minute thing. It was a new space for me to exist in. The title track is the proggiest thing I’ve ever done.”

The rest of the record is far from prog. Songs such as Somewhere Between Then And Now (about the disconnect between the myth and reality of childhood nostalgia) and the 80s-edged I Told You So sit squarely in smooth adult rock territory, albeit powered by Jakszyk’s richly emotive voice and punctuated by bursts of guitar. Those who only know him as the guy from King Crimson will be wondering why he hasn’t made a full-blown prog album.

“I don’t know,” he says. “You go wherever your head and your ears take you. Making an album that sounds a certain way implies that you’ve set out specifically to do that. And I’ve done that in the past – I’ve worked in advertising, I’ve worked to a brief, I can do all that. But I didn’t want to work to a brief with this. Wherever my imagination took me, I went. Whatever came out came out.”

What Son Of Glen lacks in knotty musicality and dizzying time changes, it makes up for in emotional resonance, especially on those songs that relate directly to Jakszyk’s life. It’s not necessary to have read the book to listen to the album, but it does add context and nuance.

Glen Tripp was a US airman who’d served in the Korean War, before being stationed in the UK in late 1957 and early 1958. That’s when he met a glamorous woman from Ballina, County Mayo named Peggy Curran, who’d sung with Irish show bands in the 50s. Peggy fell pregnant, but by the time she’d had her son – named Michael Lee Curran – Tripp had returned to the US, unaware he was a father. Less than a year after he was born, Peggy gave up her son up for adoption. He was taken in by Norbert and Camille Jakszyk, who renamed him Jakko.

Where I grew up, I only managed to avoid regularly getting a kicking by being good at football

One of the narrative strands of the book is his attempt to track down his biological parents. After giving him up for adoption, his mother remarried and moved to America and started a new family. To Jakko’s dismay, at least one of his half-siblings was an avowed white supremacist. And Tripp? The singer only discovered the true identity of his father at the age of 64. Glen had died in 1972 aged 36, when his son was just 14.

“Louise came up with this idea, almost a romantic fantasy, of, ‘What if he’s been guiding you?’” he says. “What if he was watching me make these terrible mistakes and generally fucking up? Has he been nudging me? I don’t buy into that at all, but it seemed really nice as a narrative idea.”

The song Son Of Glen is a one-way conversation with the father he never met. ‘Whose is that shape in the mirror? Knowing I’m stood here alone/Is this the ghost of my father trying to guide my way home?’ he sings. Elsewhere in the song, disembodied voices of airman flying warplanes float above the music, a nod to 1946 romantic fantasy movie A Matter Of Life And Death about a wartime airman trapped in the afterlife – “one of my favourite movies,” says Jakszyk.

It isn’t the only song to address fathers and sons and the question of how one shapes the other. How Did You I Let You Get So Old? is a reckoning of sorts with Jakszyk’s adoptive father, Norbert. In the book, he’s portrayed as a strict, distant man, though Jakko reasons it was partly down to his difficult upbringing in pre-war Poland and his sometimes horrendous experiences during the Nazi invasion, as well as the fact he was in his 60s by the time he and Camille adopted Jakszyk.

This is where I went fishing for the first and only time – with Jackie Charlton

In the mid-90s he made a documentary, The Road To Ballina, for BBC Radio 3. He took Norbert back to Poland, visiting Auschwitz and his father’s home town, recording conversations as they went. Part of one appears in How Did I Let You Get So Old?, lending the song an elegiac air – Norbert passed away in 2003.

“It was difficult for him, being an older adoptive parent, married to a French wife, neither of whom had English as a first language,” says Jakszyk. “It was difficult for me, too, being adopted by a couple who were significantly older than my contemporaries’ parents and culturally disengaged. Where I grew up, there weren’t foreign kids, so I stood out. I only managed to avoid regularly getting a kicking by being good at football. As an adopted kid, you do feel lonely, you do feel isolated. I don’t get too serious about it, but there is that sense of abandonment that sticks with you.”

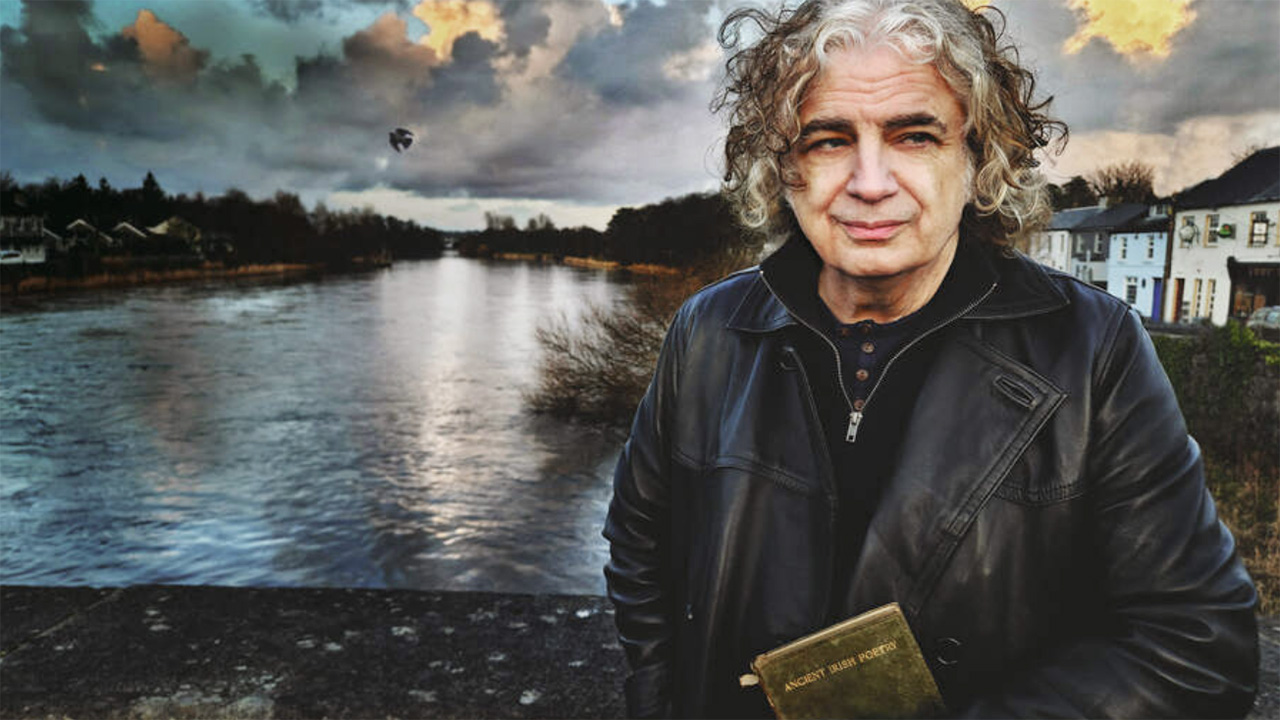

The town where Peggy Curran was born is referenced by the evocative, two-minute instrumental Ode To Ballina, which also subtly references Jakszyk’s genetic Irish heritage (the song is reprised later in the album). The press photos show him in Ballina with the River Moy behind him. He’s holding a book of Irish poetry. “It makes me look like the worst kind of American tourist, whose grandparents came from Tipperary!” he says wryly.

But he adds that he feels an understandable if intangible connection with the town. “The son of the bandleader my mum sang for had this amazing pub there. And that’s where I went fishing for the first and only time – which happened to be with Jackie Charlton.” (The unlikely story of his moment with the World Cup winning footballer is recounted in the book, alongside similarly entertaining tales of rubbing shoulders with everyone from The Nolans to Michael Jackson.)

Son Of Glen makes it clear that the musical crisis of confidence that hit him post-King Crimson has lifted – though he has no intentions of touring the album. “I’ve got no concept of where I am in those terms,” he says. “When King Crimson played in Santiago, we sold out two nights to 14,000 people a night. If I play, I’m not sure 14 people will turn up.”

I now know how I got here, but I’m no closer to knowing who I am

What is on the horizon is an extended reissue of A Scarcity Of Miracles, the 2011 album he made with Robert Fripp before the latter put King Crimson back together. There’s also talk of recording studio versions of a Crimson song played live during their final incarnation – though a few weeks after we speak, KC’s manager shuts down the idea of there being a new album.

But right now, Who’s The Boy With The Lovely Hair? and Son Of Glen seem to have closed a chapter in Jakszyk’s life. “The thing about doing a book, or even a record like this one, is that you’re looking at something in great detail on a daily basis,” he says. “You start seeing patterns of behaviour or you relive an experience that you’ve forgotten. I now know how I got here, but I’m no closer to knowing who I am.”

Son Of Glen is on sale now.

Dave Everley has been writing about and occasionally humming along to music since the early 90s. During that time, he has been Deputy Editor on Kerrang! and Classic Rock, Associate Editor on Q magazine and staff writer/tea boy on Raw, not necessarily in that order. He has written for Metal Hammer, Louder, Prog, the Observer, Select, Mojo, the Evening Standard and the totally legendary Ultrakill. He is still waiting for Billy Gibbons to send him a bottle of hot sauce he was promised several years ago.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.