“The magic has gone. I’m trying to find it in other places”: The Norwegians who abandoned black metal to re-enact the psychedelic era – covering songs that weren’t always their favourites

They were always known for genre-hopping. But their exploration the Age of Aquarius’ disintegration via obscure tracks from the era was something else again

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

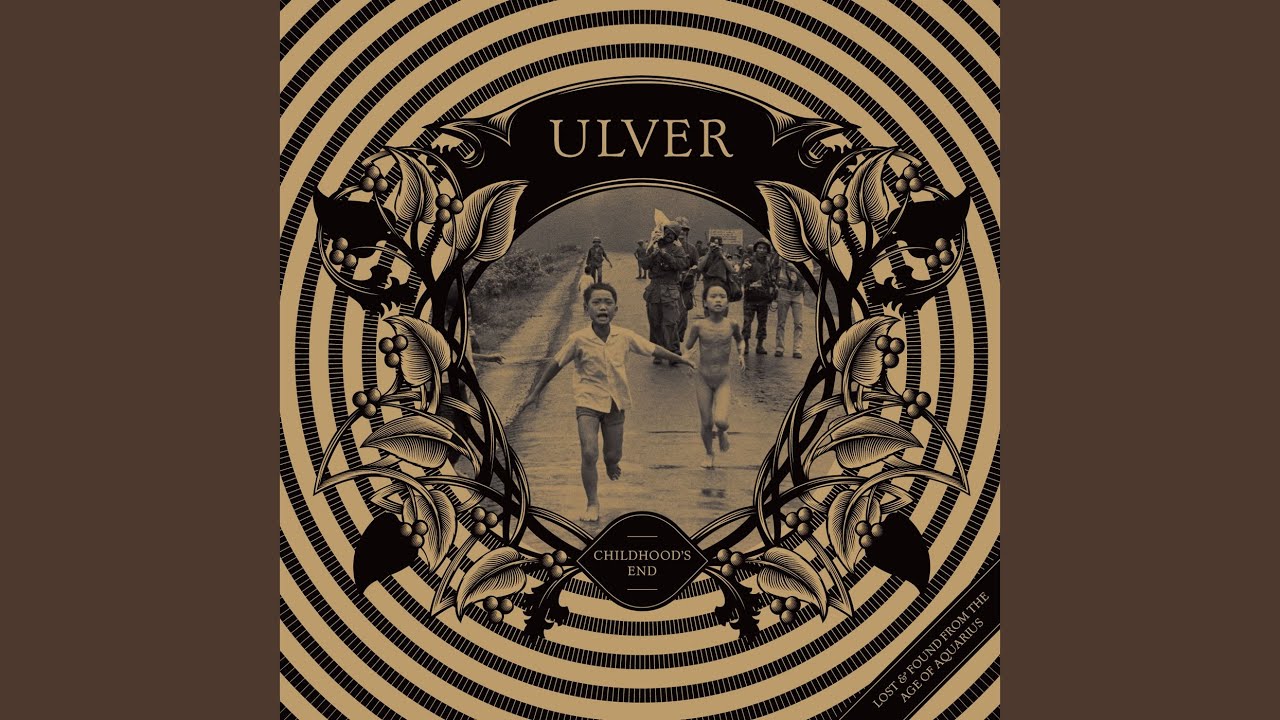

Once heroes of the sometimes-controversial Norwegian black metal, Ulver later transformed into prog high-conceptualists, techno artists and more. In 2012 they released Childhood’s End, a captivating covers album that strived to explore the cultural loss of innocence towards the end of the pyschedelic 60s. Band leader Kristoffer Rygg explained their vision.

It’s easier to say where Ulver haven’t been. The Norwegian band began as a punishing black metal combo before morphing into a progressive art-rock band with a thing for minimal ambient music, bleeping electronica, improv and symphonic pomp.

Some of their albums are more alarming than others; 1998’s Themes From William Blake’s The Marriage Of Heaven And Hell was a high-concept work that somehow combined all of the above and more. Its impact was even more startling since it followed three records largely made up of sinus-shattering rock songs about Norse legends.

Theirs is a world often viewed in freefall. As fan Julian Cope has noted: “Ulver are cataloguing the death of our culture two decades before anyone else has noticed its inevitable demise.” They’re a band who seem eternally restless, as if in dogged pursuit of some hidden, higher truth.

“You’re quite right in describing us as restless,” says the founder and leader Kristoffer Rygg, aka Garm. “We’re generally interested in all kinds of music. It would be very unnatural for me to work in a 20-year perspective in just one style or genre. You adapt and stray into different things. But sure – if you take this new album and put it next to the Metamorphosis EP from 1999, it’s a bit of a head-shaker, because that was basically techno music.”

The new album he’s referring to is Childhood’s End; described in typically grand Ulverspeak as a record that will “end all war, help form a world government and turn the planet into a near-utopia.” It also signals another abrupt turn after the ambient experimental throb and occasional noisy attack of its predecessor, Wars Of The Roses.

Subtitled Lost & Found From The Age Of Aquarius, the new release is a cache of covers from obscure corners of late ’60s psychedelia. You’ll find hallucinatory versions of songs by The Music Machine, We The People, The Beau Brummels, Les Fleurs De Lys and The United States Of America. Alongside those are better-known perennials The Pretty Things, The Byrds, Jefferson Airplane and The Electric Prunes.

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

“It was one of those projects I’d been meaning to do for some time,” says Rygg. “In my 20s I found myself coming up short with new things to like. It wasn’t until the late ’90s when I discovered a true fascination with psychedelic music, and even prog. That was when ’60s and ’70s music really took hold, and I’ve been more and more into it ever since.

“I had to do some real digging around for the songs on the album. You almost learn to rely on tip-offs, rather than sifting through entire records trying to find that one golden nugget. There’s a missionary aspect to all this too – to prove that fact that there are golden nuggets before your Black Sabbaths.

“I found a lot of useful things from that era. For example, The Electric Prunes were actually the first band to use a wah-wah pedal. That made me think of them in terms of being the birth of what we call modern music. Before that it was all blues, jazz and pop.”

Childhood’s End remains mindful of the late 60s wider societal sweep. “It was a sort of cultural movement, one that became disillusioned and quite dark,” Rygg says. “I’ve always thought that the spirituality of the era was very childlike in many ways. Then suddenly there was Altamont and Charles Manson, cocaine and heroin, and then Watergate. So the album title is quite literal.”

The most engaging aspect lies in the choice of songs. The Electric Prunes’ I Had Too Much To Dream (Last Night) and The Byrds’ Everybody’s Been Burned may be the most familiar choices on offer; but mostly it’s a head- tripping stew of blissfully stoned oddities. Among the highlights is The Trap. First recorded in 1967 by LA fuzz merchants The Music Machine, Ulver’s terrific cover is dedicated to the band’s singer Sean Bonniwell, aka Mr Black Leather Glove, who died in 2011. “I was in contact with him for a while,” says Rygg. “I spoke to him just a few weeks before he passed away. He was very keen on hearing our version of the song, but he never got to.”

There’s also a fittingly charged take on The 13th Floor Elevators’ astro- garage anthem Street Song, alongside a kaleidoscopic Soon There’ll Be Thunder, first cut by The Common People in 1969. One of the album’s most unexpected joys comes in Lament Of The Astral Cowboy, written by mercurial LA producer and arranger Curt Boettcher, one of the great unsung pioneers of sunshine pop.

“I have to admit something that’s a bit embarrassing,” Rygg says. “I thought that song was from the late 60s, but then I found out otherwise – it’s from 1973. Had I known, we wouldn’t have recorded it.” But his admission highlights the self-discipline that governed the whole venture. “There’s a mixtape angle of doing something like this,” he says.

We started the band with a very poor singer, but the criteria was very different in that day and age

“It has to be an album that you can play from the first to last track and feel like it all belongs together. I wanted to make a cohesive presentation, so they’re not necessarily our favourite songs from that era. It’s a bit more complex than that – the tracks are tied in a bit more conceptually.”

As with all things Ulver, achieving a certain feel was paramount. “We spent quite a bit of time getting the sound right, so it’s modern but also very soft-rock.” The final tracklist went right down to the wire: “We tried and failed quite a bit. The last song was chosen about a week into the mixing process – The Music Emporium’s Velvet Sunsets. We were listening to some vinyl one night with some green, feeling the vibe. Velvet Sunsets came on and we immediately thought: ‘Fuck, we need to do this!’”

Childhood’s End may be a commendable addition to Ulver’s recorded canon, but don’t hold your breath for a tour – aside from an appearance at Holland’s Roadburn Festival, the year will find the band back behind closed doors. Never known for large-scale road trips (they played two shows in their first 15 years) they remain cautious of hitting the stage. “It’s certainly done things to the band that are good, but also things that are not so good,” Rygg says.

“There’s a lot of relief to get back into studio mode. There’s a reason why we didn’t play live in the first place – it takes a lot of focus away from making new music. We’ve had some truly magical moments but it can also be very distracting. We’re not so at ease in our roles as live performers.”

Ulver’s development has taken them a ong way from their formative years on Norway’s often-notorious black metal circuit of the early 90s. “I’d say we started the band with a very poor singer, but the criteria was very different in that day and age,” Rygg says. “Being a band was a way of being part of the culture or outlook on life that was black metal.

“It was very different from what I see now. It might call itself by the same name, but it’s not what it was. And I’m not really sure I even care. It goes back to what we were saying about lost innocence. The magic has gone for me, so now I’m trying to find it in other places.”

Freelance writer for Classic Rock since 2008, and sister title Prog since its inception in 2009. Regular contributor to Uncut magazine for over 20 years. Other clients include Word magazine, Record Collector, The Guardian, Sunday Times, The Telegraph and When Saturday Comes. Alongside Marc Riley, co-presenter of long-running A-Z Of David Bowie podcast. Also appears twice a week on Riley’s BBC6 radio show, rifling through old copies of the NME and Melody Maker in the Parallel Universe slot. Designed Aston Villa’s kit during a previous life as a sportswear designer. Geezer Butler told him he loved the all-black away strip.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.