Sex workers, solitude, suicide: How The Police spun black thoughts into platinum hits on Outlandos d’Amour

Released on November 2, 1978, The Police's debut album Outlandos d’Amour helped pushed 'new wave' past punk rock and into the mainstream

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

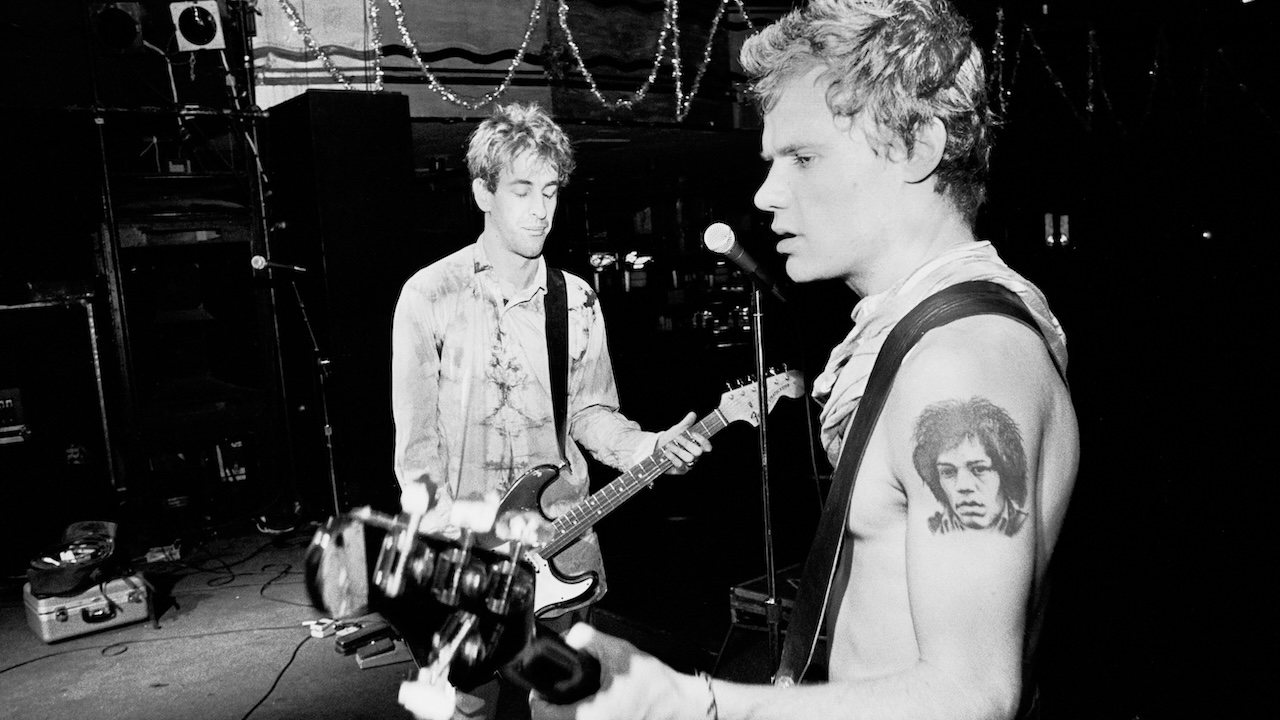

In the second summer of punk, Andy Summers, guitarist with The Police, had a houseguest. In the night’s small hours, downstairs in the living room, he could hear his bandmate, Gordon Sumner – nickname, ‘Sting’ – strumming the chords and singing the melody to a composition that would soon be known the world over as Roxanne.

In the tumultuous days of the Sex Pistols and The Clash, it was a brave move to title a song after a girl’s name; but emboldened by Elvis Costello’s pivotal single Alison, Sumner decided to press ahead with his lyric inspired by the ladies of the night plying their trade outside the band’s hotel following a concert at the Le Nashville, in Paris, in October 1977.

Hearing the music drifting up the stairs to the bedroom, Summers’ wife assured her husband that their guest was onto something.

At least at first, though, it didn’t appear so. Originally released on April 7, 1978, Roxanne, the leadoff single from The Police’s debut album, Outlandos d’Amour, which celebrates its 44th birthday on November 2nd, failed to chart anywhere in the world.

With the exception a pair of very minor appearances in the hit parades of the United Kingdom and the Netherlands for Can’t Stand Losing You and So Lonely, the group’s next two seven inches also flopped. With these and the seven other self-produced songs that complete the LP having been recorded before the trio secured a record deal (with the help of an investment of £1500 from manager Miles Copeland, the elder brother of drummer Stewart Copeland), The Police’s foothold in the scene appeared precarious.

But not for long. By the time the group unveiled their second album, Regatta de Blanc, in the autumn of 1979, Outlandos d’Amour had sold more than two million copies up and across the globe. Propelled by its three re-released singles – all hits, second time round – the LP would be rated platinum in the United States, the UK, Australia, Canada, France and the Netherlands (not to mention a gold disc in what was then West Germany). In the fullness of less than a year, turns out that their timing was immaculate after all. With the fury of punk dissipating into either memory or cliché, the conditions were suddenly perfect for a new, high-energy variant of pop rock’n’roll that would continue to excite younger listeners without necessarily aggravating or alienating radio and television programmers.

‘The Police are not punk,’ wrote John Pidgeon in a profile for Melody Maker published a month after the release of Outlandos d’Amour. ‘The Police are not disco. The police are not heavy metal. The Police are not power pop. The Police are the best rock’n’roll band I’ve seen in years. I kid you not.’

In fact, the term was ‘new wave’. Although none of its practitioners would use the description in anything other than mocking terms, The Police, along with Elvis Costello & The Attractions, Squeeze, XTC and the Boomtown Rats, formed a vanguard of thrilling music, much of which sounds as fresh and resonant today as it did on its week of release.

By comparison to the highly-polished material that would follow – one thinks of the ubiquitous Every Breath You Take single, from 1983, which just last month passed the milestone of a billion streams – Outlandos d’Amour is a somewhat unpolished diamond mined by a group whose signature sound had not yet reached its fullest form. This being said, the technical prowess of the three musicians, combined with the song-writing savvy of Sting - who is credited as the sole author of all but two of the LP’s tracks – united to deliver a debut that conveys both energy and substance in equal measure.

For a group that would quickly become pop stars, and even pin-ups, the songs with which The Police introduced themselves were hardly splashes of lyrical sunshine. In the musically effervescent Can’t Stand Losing You, the common-or-garden difficulty of being ditched by a lover is imagined as a problem that can only be avenged by suicide. “I guess this is our last goodbye,” sings Sting, “and you don’t care, so I won’t cry, but you’ll be sorry when I’m dead, and all this guilt will be on your head.” Wow

On So Lonely, a disconsolate narrator invites a guest, real or imagined, to “Take a seat, they’re always free, no surprise, no mystery”. And why might that be, you may ask? Well, because “in the prison that I call my soul, I always play the starring role”. Okay.

The latest news, features and interviews direct to your inbox, from the global home of alternative music.

By the time The Police called time on their recording career, in 1983, they had, over the course of five studio albums, become one of the great singles groups of their age. Certainly, the prominence of smash hits such as Message In A Bottle, Walking On The Moon and Every Little Thing She Does Is Magic eclipsed many a deeper cut hiding in plain sight on each and every LP. Such is the wealth of material on Outlandos d’Amour, in fact, that it’s tempting to imagine that its success would have been equalled had its authors opted to release three different singles for public consumption.

For example, opening track, the taut and energetic Next To You, would surely have made itself right at home on the radio alongside the likes of Pump It Up and Rat Trap. Elsewhere, Born In The 50’s [sic], features a chorus that is almost the equal to that of Roxanne. With equal élan, it’s not difficult to picture the throttled urgency of Truth Hits Everybody doing much the same job on the hit parade as So Lonely.

With Outlandos d’Amour The Police ignited the booster rockets on a career that, though relatively short-lived in its original incarnation, was still gaining momentum at the time its members decided to call it a night. In fact, such was the enduring appeal of their most famous songs that a reunion tour in 2007 and 2008 saw the group appearing in only the world’s largest indoor and outdoor venues.

No quite so lonely after all, then.

Barnsley-born author and writer Ian Winwood contributes to The Telegraph, The Times, Alternative Press and Times Radio, and has written for Kerrang!, NME, Mojo, Q and Revolver, among others. His favourite albums are Elvis Costello's King Of America and Motorhead's No Sleep 'Til Hammersmith. His favourite books are Thomas Pynchon's Vineland and Paul Auster's Mr Vertigo. His own latest book, Bodies: Life and Death in Music, is out now on Faber & Faber and is described as "genuinely eye-popping" by The Guardian, "electrifying" by Kerrang! and "an essential read" by Classic Rock. He lives in Camden Town.