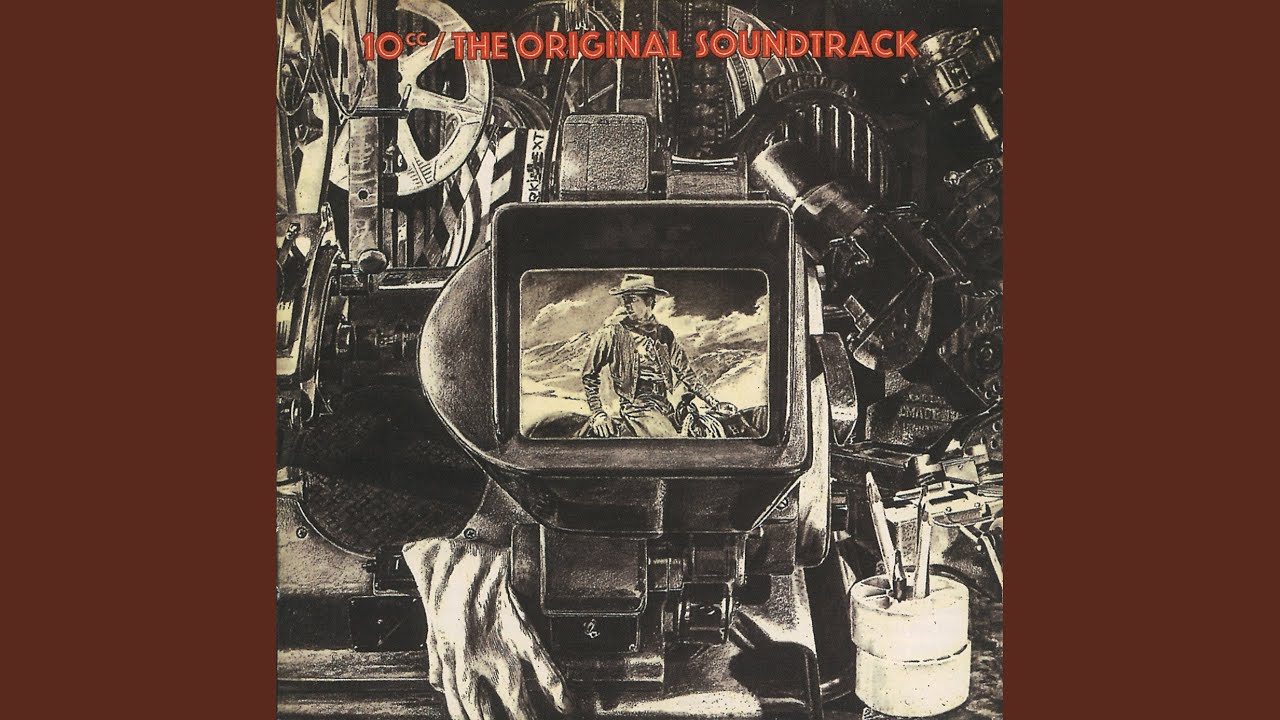

“Prog? There was a university pretentiousness about it. People asked what we did and I’d say, ‘10cc music’”: However you describe it, The Original Soundtrack is a progressive landmark

Their third album, complete with I’m Not In Love, moved away from three-minute singles and embraced opera and concept pop. Did it also inspire Queen’s Bohemian Rhapsody?

10cc were established masters of the three-minute pop song when they moved towards rock operatic and pop conceptual for 1975’s The Original Soundtrack. In 2011 Graham Gouldman talked Prog through its creation, and addressed the rumour that the track Une Nuit A Paris inspired Queen’s Bhohemian Rhapsody.

By 1975, with hit singles such as Donna, Rubber Bullets and The Dean And I, 10cc had mastered the three-minute pop song – albeit a version crammed with more musical and lyrical ideas than most bands managed to fit into entire albums. Their self-titled debut album (1973) and follow-up Sheet Music (1974) were dazzlingly inventive, earning comparisons in the music press with the very best. “They’re the Beach Boys of Good Vibrations, they’re the Beatles of Penny Lane – they’re sheer brilliance,” wrote Melody Maker.

The concern that arose for the Manchester four-piece was how to sustain such a level of invention without doing the unthinkable for a band who recoiled at the obvious: resorting to formula. The answer was to make a third album including, on one side, a heavy metal track about the return of Jesus Christ, a cartoon ditty about life and death, and surely the first ever example of Mancunian gospel; and on the other, a nine-minute tripartite song-suite about a night in Paris, and a six- minute love song which was never intended as a single but became a landmark example of the form.

The sonic ambition of The Original Soundtrack was created by 10cc’s four multi-instrumentalists, songwriters, producers at Strawberry, their state-of-the-art studio in Stockport. With its intricate musicianship and elaborate songcraft – not to mention the sleeve art by Hipgnosis – did they consider it as a move towards prog?

“No,” replies Graham Gouldman, nominally the bassist of the band; although, like colleagues Eric Stewart, Lol Creme and Kevin Godley, he was no stranger to multi-tasking. “We didn’t like prog – there was a university pretentiousness about it. We never liked being pigeonholed anyway. People would ask what kind of music we were and I’d say, ‘It’s 10cc music.’

“There was complexity and ambition on The Original Soundtrack, but that doesn’t mean it was prog,” he adds. “‘Progressive’ is about right. The Beatles were progressive and innovative, and 10cc were as well. ‘Prog ’meant pretension, and we never pretended to be something we weren’t, although some people had other views: that we were too clever for our own good, clever-clever, smarty-pants. We were just trying to do something different.”

Like The Beatles, 10cc didn’t just turn up with a bunch of songs to rehearse, perform and record. Rather, they used the studio as the starting point for their compositions, which could move in any direction with all the faders, flangers and devices at their disposal (they even invented a gadget for producing new sounds on a guitar called, funnily enough, The Gizmo).

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

“Eric had had experience of being a frontman in the 60s with Wayne Fontana And The Mindbenders, but really we were born in the studio,” says Gouldman. “The studio became like a partner in the songwriting process. You could start off with some weird sound and build on it and not know where it was going to go.”

He cites I’m Not In Love as an example – what began as a pleasant little bossa nova tune became a sumptuous, multi-layered six-minute extravaganza featuring a 250-voice male choir. Trevor Horn, for one, was listening intently: a huge 10cc fan, you can trace a line from I’m Not In Love to his early-80s productions for ABC, Dollar and Art Of Noise.

“Lol had this great idea to do a backing track featuring a choir,” recalls Gouldman. “We developed a method by which we could get up to 200-odd voices using a 16-track machine. We filled those 16 tracks with my, Kevin and Lol’s voices, because Eric was at the controls.”

We knew we’d created something special… we’d lie on the floor of the studio, turn off the lights and let it wash over us

The process then involved a time-consuming and arduous use of the faders on the mixing desk almost like notes on a keyboard, which each of the members ‘played’ to get the right sounds. Necessity was the mother of invention. “It was like, ‘How the hell are we going to make 200-odd voices? Think think think!’”

With all this madcap experimentation, were any drugs consumed in the making of this music? “Heaven forfend!” Gouldman laughs. “There was maybe a little bit of dope knocking around.”

He agrees that I’m Not In Love was a game-changer that set pop onto unforeseen paths. “All I can say is we knew we’d created something special, no doubt about it,” he says. “We’d lie on the floor of the studio, turn off the lights and let it wash over us.”

It was a Gouldman-Stewart composition, but there was another, equally formidable opus that opened side one of The Original Soundtrack entitled Une Nuit A Paris, written by Messrs Godley and Creme. 10cc were arguably the only major rock band in history featuring four equally gifted songwriters, who on their first two albums wrote in every conceivable permutation, with wildly disparate results – a Creme/Gouldman track like Worst Band In The World, for example, would be radically different to a Godley/Stewart tune like Oh Effendi. Think of them as exponents of ‘total pop’ – like the Dutch ‘total football’ squad of 74 who could play in any position.

By the third album they had largely settled into the Gouldman/Stewart and Godley/Creme axes, although the idea that the former pair were the McCartney (conventionally melodic) to the latter’s Lennon (witty and experimental) was, says Gouldman, “ridiculous.” He explains: “It’s neat and convenient – but really I wouldn’t mind being McCartney on Helter Skelter. Anyway, both were fucking geniuses.” Besides, Godley and Creme could be melodic, and Gouldman and Stewart could be acerbic. He does concede, though, that “Kevin and Lol were generally more innovative in the studio,” adding that “Eric was a fine producer” and that they’d all participate in the process of sound invention.

Happy’s not so much fun. Dark is good. And melancholy – I love melancholy

And there were a lot of sounds – and instruments – on The Original Soundtrack, including piano, guitar, mandolin, autoharp, Moog, violin, bongos, marimba and timpani. You name it, 10cc had a go at playing it. “It worked brilliantly with a million-pound studio,” says Gouldman modestly. “That helped, being plugged into that.”

He remembers there being a different atmosphere at Strawberry for the third album sessions. “It felt more serious. There was a sense of doing serious work, with long, substantial pieces like I’m Not In Love and Une Nuit A Paris.”

The latter was a mini-rock opera that came in three parts and told the story of a British tourist being fleeced in the French capital by ladies of ill repute. Godley and Creme originally wanted it to take a whole side of the album, but Gouldman and Stewart intervened and it was edited down to a mere eight minutes and 40 seconds. “It was the most fun to record, trying to recreate Paris in Stockport,” says Gouldman, who agrees that “sonically, it was amazing,” even though it wasn’t as busy as it sounded.

“It was mainly piano, bass and drums, and lots of voices. But it feels like more is going on because we did it right. If you’ve got a good song, unless you’re a complete idiot, you let the song dictate. That way, it’s harder to make a mess of it. You can’t, as they say, polish a turd; but a good song inspires you to come up with good production.”

It was so good, in fact, that many have surmised that Queen based their own pop operetta on Une Nuit A Paris. Gouldman has his own views on the subject. “Let’s say they heard it before they did Bohemian Rhapsody – those fucking bastards!” he says, albeit with a chuckle.

Kevin and Lol played Brand New Day to us and it was like, ‘Were you born on the Delta, or in Prestwich?’

Having just signed a million-pound transfer fee that took them from Jonathan King’s UK label to Mercury, what did 10cc’s new paymasters make of their charges’ latest album, with its lengthy side opener and potential six-minute single? “Jaws hit the floor,” remembers Gouldman. “I don’t know what they expected. Sheet Music featured more concise songs. This had two major, long pieces. But I think they were pleased.”

In his review of the album, NME critic Charles Shaar Murray opined that, in terms of darkness of tone and gravity of atmosphere, “The Original Soundtrack makes Sheet Music look like Mary Poppins.” With tracks such as Blackmail (which might have been inspired by the sex scandal involving Liberal MP Jeremy Thorpe), the hard-rocking The Second Sitting For The Last Supper and Flying Junk, he had a point – even if the latter was written, insists Gouldman, about a boat, not smack. “Happy’s not so much fun,” he says. “Dark is good. And melancholy; I love melancholy.”

The Original Soundtrack came a mere year before 10cc’s split into two camps, following the release of fourth album How Dare You!, when Godley and Creme became a recording – and video-directing – double act and the other two continued as 10cc. Were relationships unravelling during the recording of the third record?

“Not really,” he says. “There was the odd incident. Nothing like it was with How Dare You! – that wasn’t so great. But on Soundtrack we still managed to come up with the goods.” He was especially pleased with the “tongue-in-cheek heavy metal” of The Second Sitting For The Last Supper and the bluesy Brand New Day. “That was a great song. But it was almost like, ‘Where the fuck did that come from?’ I remember Kevin and Lol played it to us and it was like, ‘Were you born on the Delta, or in Prestwich?’”

The album closed with Life Is A Minestrone, a Creme/Stewart team-up that, according to Gouldman, “raised the question, ‘What is death?’”; and The Film Of My Love, a “massive piss-take” of a lachrymose love serenade. “It was cheesy,” he grins. “Cheese gone off – that was the idea.”

The title of the final track added to the sense of The Original Soundtrack as a noir movie, although it wasn’t designed as a concept album. But he regards it now as a masterwork, even if he does prefer Sheet Music. “We knew it was really good,” he says.

We weren’t that visible or high profile. And we didn’t get up to stuff

Good enough to build bridges between the various warring factions and get back in the studio, or for one final run-through of the album live? “Nobody wants to get back together,” says Gouldman. “I have a version of 10cc on the road, and the only other person who would possibly do something is Kevin – in fact, we did a DVD at Shepherd’s Bush a few years ago and Kevin appeared on it. But certain people don’t want to be in the room with certain other people. How sad is that?”

He’s also slightly perturbed by the way 10cc have been airbrushed out of history, despite being arguably the biggest pop-rock band in the UK before punk, and despite being cited as an influence by everyone from Air to The Flaming Lips. “When people think of the 70s, they think of Bowie, Queen, T Rex or Sweet – not 10cc,” he argues. “We weren’t that visible or high profile. And we didn’t get up to stuff.

“Plus there were four of us who all did different things, including sing, so it was hard for people to focus, which is why we haven’t been given our due. But what other band could boast four singers, songwriters and musicians? The Beatles had three. We had four. 10cc were on their own.”

Paul Lester is the editor of Record Collector. He began freelancing for Melody Maker in the late 80s, and was later made Features Editor. He was a member of the team that launched Uncut Magazine, where he became Deputy Editor. In 2006 he went freelance again and has written for The Guardian, The Times, the Sunday Times, the Telegraph, Classic Rock, Q and the Jewish Chronicle. He has also written books on Oasis, Blur, Pulp, Bjork, The Verve, Gang Of Four, Wire, Lady Gaga, Robbie Williams, the Spice Girls, and Pink.