Pet Sounds: The story of how the Beach Boys helped inspire progressive rock

Taking inspiration from Arthur Koestler’s Act Of Creation with themes of love, hope, regret and sorrow, The Beach Boys’ masterpiece confounded those expecting more songs about cars and girls

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

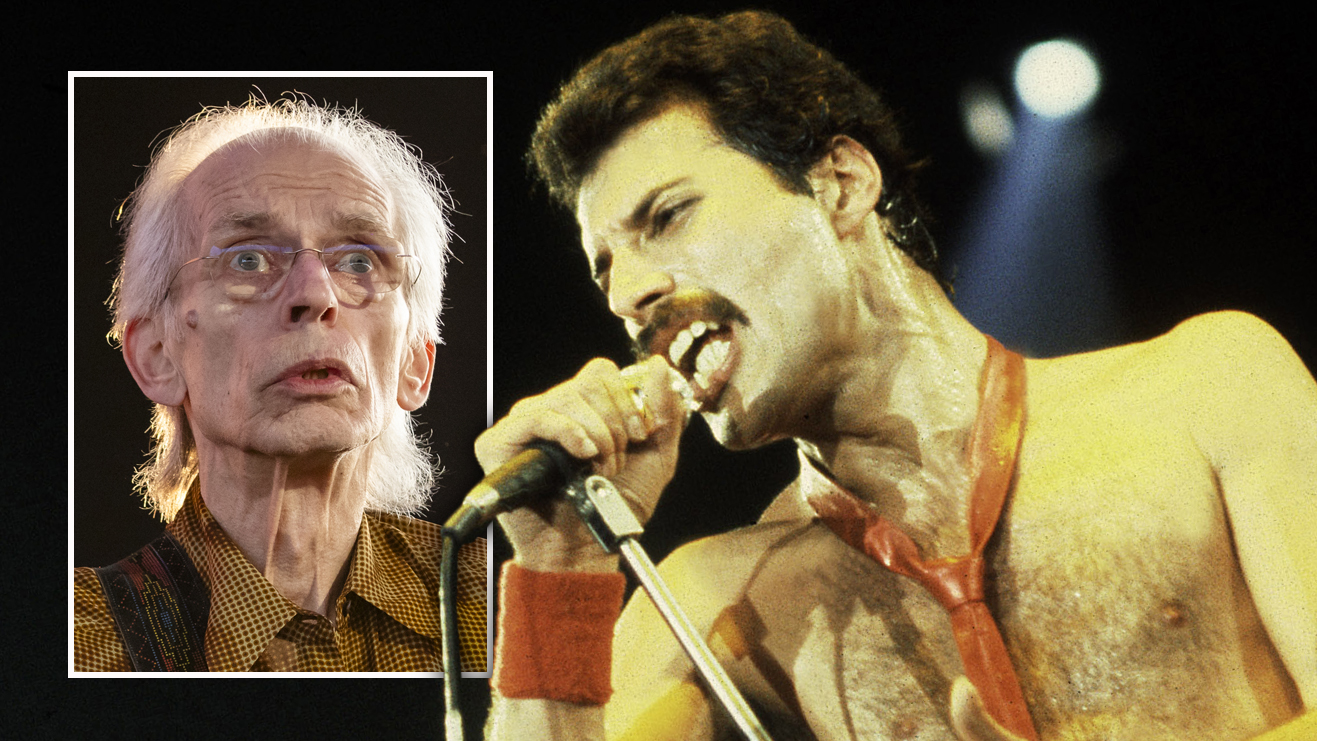

"I believe that without Brian Wilson’s inspiration, Sgt Pepper might have been

less of the phenomenon that it became,” Beatles producer George Martin is quoted as saying in Charles L Granata’s book, Brian Wilson And The Making Of Pet Sounds. “Brian is a living genius of pop music. Like The Beatles, he pushed forward the frontiers of popular music.”

Martin and the Fab Four weren’t the only ones whose minds were blown in summer of 1966 by The Beach Boys’ great leap forward. Bruce Johnston – who had been drafted in to replace Brian Wilson for gigs, after the latter’s nervous breakdown in 1964 and subsequent retreat into the recording studio – remembers being the emissary on Pet Sounds’ release. He took an acetate of the album to London on a trip designed to spread the word among rock’s hiperati, occupying a hotel suite where he played it to John Lennon, Paul McCartney, Keith Moon and Mick Jagger’s girlfriend Marianne Faithfull, all of whom were struck dumb by what they heard. And soon the cream of British musicians – including Graham Nash, Rolling Stones manager Andrew Loog Oldham and, well, Eric Clapton’s Cream – were in thrall to Wilson’s meisterwerk.

Forty-six years on, Brian Wilson is still proud of his achievement on Pet Sounds, and also of the world’s rapturous response to it.

“Well, yeah, of course,” he says. “Wouldn’t you be proud, too?”

In Wilson’s view, and that of Beach Boys über-fans, the group actually made their first tentative steps towards the sort of sophisticated music heard on Pet Sounds on the 1965 album Today!, whose second side comprised a suite of intricately arranged ballads. “I don’t remember the sessions, but I do remember we had a good time doing it,” he says of Today!. It was the album where a large number of musicians were drafted in to realise his grandiose symphonic dreams: it featured Hal Blaine on drums, Carol Kaye on bass and all of the other session players who made up what was affectionately known as the Wrecking Crew.

But they were used to most spectacular effect on Pet Sounds. And despite being something of a mad professor, and his later reputation for dysfunction and mental debility due to prolonged drug use, the Wilson you can hear barking (no pun intended) commands on the 1997 Pet Sounds Sessions box set, on which you can hear the tracks evolve, is in full control of proceedings as he marshals the multitudes before him.

“I used to refer to him as the Stalin of the studio,” laughs Mike Love, Wilson’s cousin and singer on many of the Beach Boys hits. “He was totally in command up to Pet Sounds and Smile [the legendarily aborted project Wilson undertook after Pet Sounds, with collaborator Van Dyke Parks]. After that, the influence of LSD made him withdrawn, a recluse almost.”

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Wilson talks in terse monosyllables, eager to be anywhere but here, being interviewed by Prog about his most famous work. At times he can seem like a fidgety, barely interested kid at school – Adult Child is the name of an unreleased album that Wilson worked on simultaneously to Smile (another unissued Wilson album came out in bootleg form in 1992, its title: Sweet Insanity). But he focuses in fits and starts as he recalls the highlights of that momentous period.

Wouldn’t It Be Nice may have been the opener but side one’s closer Sloop John B was the first track completed – a cover of an old folk song, it was the anomaly on this song cycle about love and hope, regret and sorrow, and yet its lustrous orchestration was typical of the record. The other Beach Boys – Brian’s brothers Carl (guitar) and Dennis (drums), plus Johnston, Love and Al Jardine (guitar) – may have barely contributed instrumentally (That’s Not Me was one of their few showcases as musicians), but their harmonies throughout are stunning: on the hymnal You Still Believe In Me they sound like a choir. The chord sequence for Don’t Talk (Put Your Head On My Shoulder) was so affecting it reduced Brian’s then-wife Marilyn to tears. I Know There’s An Answer was originally going to be called Hang On To Your Ego but it was Love who apparently deemed it too weird and druggy and insisted on the change. I Just Wasn’t Made For These Times was the perfect title for this staggeringly beautiful song about alienation. There were two instrumentals on Pet Sounds: Let’s Go Away For A While, which nodded to that other sublime 60s melodist Burt Bacharach, and the title track, briefly mooted as a James Bond theme (under the title Run James Run). Finally, there was Caroline, No, a deeply autobiographical song – the only one on the album to feature lyrics penned by Brian – full of yearning for a girl, and a past, that could never be recovered. It was actually issued as a Brian Wilson solo single, although as he recalls, it hardly charted.

“It didn’t go over very well,” he says. “But it was a very pretty tune.”

Many of the lyrics on Pet Sounds were penned by a young advertising copywriter called Tony Asher, who managed to succinctly express Wilson’s feelings. Was he his surrogate therapist?

“Yeah,” says Wilson. “Exactly!”

And yet despite Asher’s involvement, and that of the Beach Boys and sundry musicians, given the fact that he wrote all the music and produced it, was Pet Sounds really the first Brian Wilson solo album?

“Yeah, kind of,” he says, warming to the idea. “In a way, yeah.”

Mike Love, who penned the words for many of The Beach Boys’ songs before Pet Sounds, was a voracious reader himself. Although he is best known for his lyrics to hits such as Fun, Fun, Fun and California Girls, which crystallised the idea of the band as frothy pleasure-seekers, it was Love who heard Wilson’s deeply sad music for the pre-Pet Sounds ballad The Warmth Of The Sun and came up with a poignant lyric for it about loss (it was written on the eve of the assassination of President Kennedy); and it was Love who contributed the words to Pet Sounds’ Wouldn’t It Be Nice, I Know There’s An Answer and I’m Waiting For The Day, which essayed a sort of pop existentialism.

“I was reading just about every kind of philosophy there was, from Rosicrucian to Vedic, and poets such as Emerson,” he recalls of the time. “I guess that’s what made me the songwriting partner for Brian, because I had a natural affinity for concepts and lyrics.”

Love would write the lyrics to Wilson’s next sonic departure, Good Vibrations, a boy-girl love song wrapped in LSD clothing, all psychedelic imagery and flower-power vibes. He notes the two camps in The Beach Boys – those that experimented with stimulants (the Wilson brothers), and the Love/Jardine/Johnston axis, that didn’t. Nevertheless, it was Love who became a proponent of Transcendental Meditation, grew long hair and a beard and travelled to meet the Maharishi. Has his reputation as the square Beach Boy, the one resistant to Wilson’s progress, been overstated?

He cites God Only Knows as the song where he knew Pet Sounds was going to be special. He wasn’t the only one.

“Paul McCartney said he thought it was the best song ever written,” he says, still delighted.

Wilson remembers listening to Rubber Soul and Phil Spector in the run-up to recording, as well as Bach: the first gave him the impetus to create an album that cohered as a whole, the second taught him everything there was to know about building a gorgeous wall of sound, and the third encouraged him to pursue a baroque direction.

Was he intimidated by all the violinists, saxophonists, cellists and harpsichordists ranged before him?

“It was exciting and scary both,” he says, laughing uneasily, although when Prog asks whether he got the results he wanted, he replies, “Oh, yeah.”

Is he aware of the impact that his lushly experimental music had on the rock scene?

“Not at the time,” he remembers, “but just lately I’ve become aware of how much Pet Sounds has influenced musicians.”

It was progressive music, wasn’t it? “Yes,” he agrees, “it was.”

Did his experiments with mind-expanding drugs prove crucial to the development of the music?

“Well,” he considers, “it taught me how to be better at making music.”

Apparently Wilson was particularly enamoured, during the making of Pet Sounds, with a philosophical treatise by Arthur Koestler called the Act Of Creation. What did he learn from it?

“I learned that humour was more important to a person than art or science,” he says.

“There was no resistance to Pet Sounds,” he says, not angry at the thought, but rather hurt. “There was a ‘them and us’ culture with regard to drugs, but I never was against Pet Sounds. That’s somebody’s fabrication that has become popular over the years. I actually named the album because at the end of it there’s a dog barking and a train going by, and I went with Brian to present the album to [record company] Capitol, who didn’t know what to do with it because they were expecting more songs about hot rods and surfing. But I was not unfavourable to Pet Sounds at all. I and the rest of the guys worked hard to make those harmonies perfect.”

Love, however, is in accord with the rest of the world in acknowledging that, on Pet Sounds, Wilson “was at the top of his game”. He also considers the music contained on it to be “as avant-garde as pop has ever got”.

“It’s purely experimental,” he decides, before adding, “with zero regard for commerciality.”

And yet there it was, voted second only to Sgt Pepper in a recent Rolling Stone poll of the 500 greatest rock albums of all time.

Wilson wasn’t aware of the list. But he’s delighted when he finds out.

“I’ll be gosh darned. I didn’t know that,” he says.

Did he ever imagine people would still be talking about it 46 years later?

“I never did, no.”

As for Love, he says jokingly of a voting system that placed The Beach Boys as runners-up to The Beatles: “I demand a recount!”

Has he ever played both albums back to back, to determine which really is best?

“No, I haven’t,” he says, adding drily, “but I’ll get right on it.”

Originally published in Prog 33.

Paul Lester is the editor of Record Collector. He began freelancing for Melody Maker in the late 80s, and was later made Features Editor. He was a member of the team that launched Uncut Magazine, where he became Deputy Editor. In 2006 he went freelance again and has written for The Guardian, The Times, the Sunday Times, the Telegraph, Classic Rock, Q and the Jewish Chronicle. He has also written books on Oasis, Blur, Pulp, Bjork, The Verve, Gang Of Four, Wire, Lady Gaga, Robbie Williams, the Spice Girls, and Pink.