The story behind Metallica's 72 Seasons: "We love what we do, and we love each other"

Metallica have gone from being a cult metal band to a commercial juggernaut and a household name. But even with new album 72 Seasons storming charts worldwide they’re still figuring out what it's all about

Ablue-skied mid-morning in Lisbon. It’s Carnival Tuesday, February 21, in the Portuguese capital and a national holiday across the country. A marching band are already striking up an imploring samba rhythm from the grand riverfront plaza, the Praca do Comercio. Lines of Mardi Gras revellers in brightly coloured costumes snake along the length of the Rua Serpa Pinto. This vaulting thoroughfare spears off the from the plaza and up the steep hill leading to the skeletal remains of the Convento do Carmo, its Gothic pillars and arches looming over the city like the carcass of a great, gutted whale.

There’s a crowd gathered at the head of the road, in the shadow of the ruined convent. In their midst a solitary musician, a busker, is picking out a weeping melody on a battered acoustic guitar. The song is better suited to the dead of a long, dark night than a street party, and at once familiar as being Nothing Else Matters.

Such is Metallica’s enduring ubiquity in this, their forty-second year. Their sheer staying power is remarkable. It’s approaching 32 years since Nothing Else Matters’ parent record, Metallica, aka the Black album, roared out. More than six since Metallica last released an album of new music.

Not that the band have ever truly gone away. Last summer they played shows – festival headliners and their own stadium dates – in a handful of European cities, including Lisbon. These were trailblazers for November’s clarion-call single Lux Aeterna. Two more new songs – Screaming Suicide and If Darkness Had A Son – have followed. They are precursors to the release of 72 Seasons, the first Metallica studio album since Hardwired… To Self-Destruct back in 2016.

What’s more, this rush of activity has chimed with the band attaining a level of hipness without precedent in all the rest of their 125-million-records-sold-and-counting time together.

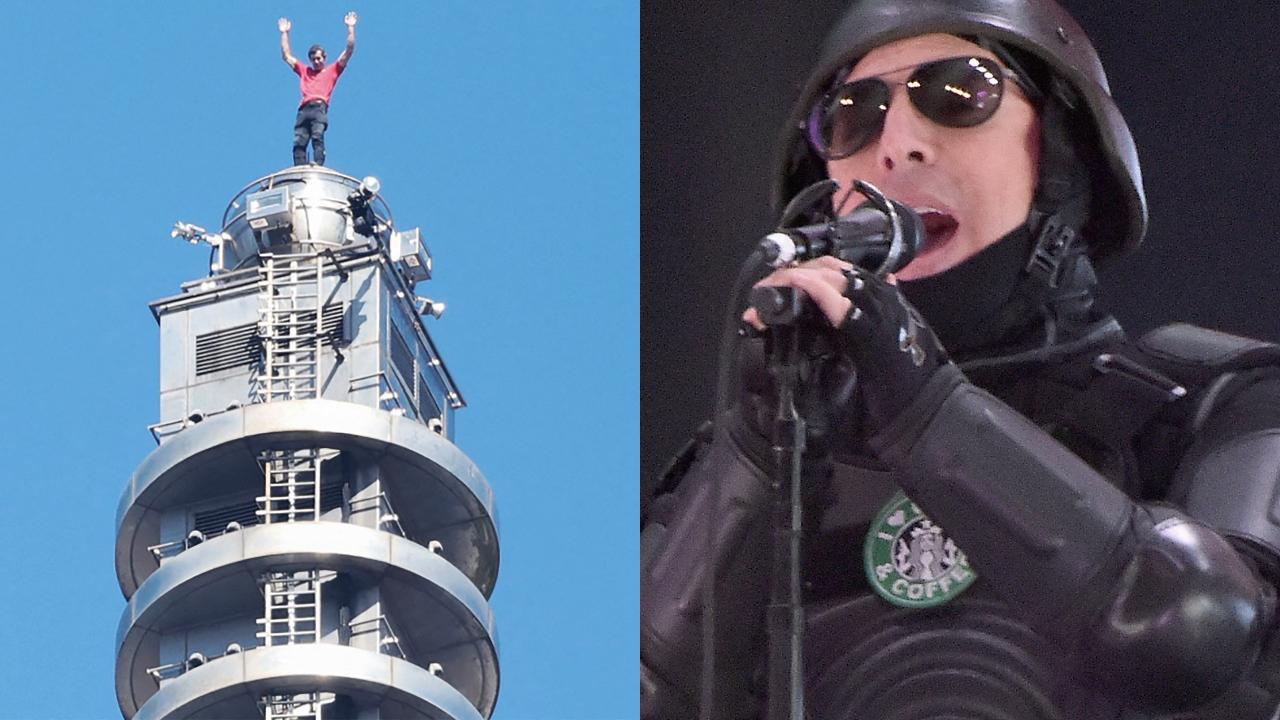

Put another way, Metallica are riding the wave of the Stranger Things effect. More accurately, the grandstanding moment in season four’s finale episode when Hellfire Club metalhead Eddie Munson cranked out Master Of Puppets from the roof of his trailer in the Upside Down. It was, in fact, Metallica bassist Robert Trujillo’s 18-year-old son, Tye, playing the re-recorded riff (the young Trujillo’s third-grade teacher happens to be married to one of the show’s producers).

Tye Trujillo recorded his part at a tiny studio in Venice Beach, unbeknown at the time to James Hetfield, Lars Ulrich and Kirk Hammett. Since the Stranger Things episode aired last July, the original Metallica track has had more than half a billion streams on Spotify. The band were also the subject of a weighty profile piece in august, scholarly American magazine The New Yorker (among its other recent, and more typical, profile subjects are Salman Rushdie, American-Iranian conceptual artist Tala Madani, and Swiss explorer Bertrand Piccard).

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

On another mid-February morning, Lars Ulrich, Kirk Hammett and Rob Trujillo are at their homes in, respectively, San Francisco, Honolulu, and Topanga Canyon – a hop to the west of Los Angeles. It’s seasonably mild in California and, reports Hammett, raining sideways in Hawaii. Each of them, Ulrich especially, is in relaxed but expansive mood.

As well they might be. The three new songs have been met with an overwhelmingly positive response from the Metallica faithful. Their combined crackle of electric energy and urgent intent ramped up by the videos accompanying them – slickly stylised, attention-grabbing clips, the work of New York-based photographer/filmmaker Tim Saccenti, who also counts Depeche Mode and Coldplay as clients. Everything in Metallica world just now has the look of being in ship-shape working order, a well-oiled machine.

In the past few weeks, Ulrich has set himself to taking stock of 72 Seasons as a whole, complete piece. He’s been listening to it most often while looking out of the window of a moving car, and also whenever he’s working out at home. He likes the songs, he says, adding the caveat: “I haven’t quite figured anything more out,to be honest.

“I’m preparing myself for the barrage of different opinions,” he continues. “And no opinion is not worthy! When you haven’t shared any new music for six years, it’s nice just to press the button and get it out of the house, so to speak. It’s an exciting time.”

In the manner of its beginning, at least, 72 Seasons took shape like no other Metallica record. By Ulrich’s estimate, the band officially started work on it during the late summer of 2020, and when still in the teeth of the covid pandemic. Self-isolating at home, they communicated with each other via Zoom meetings.

Up to then, Ulrich says he’d passed the various lockdown periods “hobbling along trying to figure out whether I should binge-watch forty episodes of The Crown this week”. Hammett “played guitar and increased my meditation time considerably. What else was I going to do? Oh yeah, and I made a solo record (last year’s Portals EP). I forgot that part.” Trujillo taught himself to cook (speciality dish: Mexican enchiladas with a secret sauce). In general, Ulrich considers, the experience was “a complete mind-fuck”.

The band’s actual nuts-and-bolts processes survived the ordeal intact. Their starting point was their usual one: Ulrich sifting through the piles of accumulated recordings made variously at rehearsal-room jam sessions and sound-checks, in hotel rooms and during backstage warm-ups over the years intervening Hardwired…, and extracting the bare bones of ideas for the band to develop going forward; a snatch of a riff of here, the hint of a counter-melody there.

It was all scrutinised through the lens ofthe drummer’s own five-star rating system: anything deemed four or above worthy of greater attention, the twos and ones consigned to history.

“In Metallica, it’s not as if somebody ever picks up an acoustic guitar on a couch and – bam! – there’s a song,” says Ulrich. “It’s many pieces of puzzles and connecting the bits. Then we started listening to and jamming through the stuff we’d picked out and on our Zoom sessions, sat behind computer screens in our home studios or makeshift music rooms.

“Dealing with how you make music when everything has a two-second delay. I would be playing a drum beat and James putting a riff over it. He could hear my drums, but I couldn’t hear his guitar. Or vice-versa. It wasn’t conducive to maintaining your sanity. We were sort of stumbling ahead and with all the uncertainties of calendars, lockdowns and the human condition. For a few months there we moved forward very, very slowly. Progress was glacial.”

When eventually they were able to convene again at the band’s home base, HQ – their sprawling studio-come-rehearsal facility in San Rafael, a 30-minute drive from San Francisco, where every Metallica album since the ill-fated St. Anger has gone down – it was in the ‘new normal’ state of things. Which is to say with everyone having to take covid tests every morning and maintain a safe distance from each other in the studio.

Joining them at HQ was Greg Fidelman, a team fixture ever since he’d been Rick Rubin’s right-hand man on 2008’s Death Magnetic album, and having then stepped up to helm Hardwired… The sessions were interrupted once more with the band breaking off to honour touring commitments in North and South America and Europe, held over from the pandemic, but otherwise, say the principals, proceeded relatively hitch-free. ‘Civilised’ is the word Ulrich chooses to describe the pervading atmosphere.

“The difference these days is we’re maybe more respectful of each other,” he says. “We listen more to each other. There’s less of the ‘Fuck you’, and more of ‘That sounds interesting, let’s try it your way.’”

“When we were working by Zoom, a lot of that weird energy and chemistry was dissipated,” says Hammett. “It was there still, but not as strong. So many of the great things that happen with us as a band are the result of the four us being together in the room. Coming up with ideas is not really a challenge. Between the four of us we have so many fucking great ideas.”

Still, from outset to finish, 72 Seasons gobbled up two years. Debut album Kill ’Em All was done and dusted in not much more than a couple of weeks of May ’83.

“As you get older, the good thing is you have more experience, and the bad is it affords you more options,” says Ulrich. “The more options, the longer thing take because you feel this inherent need to go over every one of them. You can spend a day trying to weed nine options down to one or two. And of course there’s a part of you romanticising how when you were twenty-two you did it instinctively, without having to fucking think about it.”

Ulrich and Hetfield both turn 60 this year. Hammett reached that milestone in November last year. Together, and separately, and ever since the Black album rampaged its way into the global consciousness, the three of them have serially appeared to be grappling with the question of exactly what Metallica should be. And also how best – and if at all – they should go on being Metallica. With Jason Newsted on bass through the Load/Reload era of haircuts, eyeliner, arty videos and album covers made up of blood and semen. Then with Newsted’s successor Trujillo, a sprightly 59 this October, on board from St.Anger onwards.

Trujillo recalls his initiation into the band as “a wild ride – a roller-coaster”. Small wonder, given that he arrived in the wake of Hetfield’s well-documented disappearance to rehab and the ensuing turmoil when hapless ‘life counsellor’ Phil Towle was engaged to try to fix their fracturing intra-band relationships. The whole mess of it was preserved for posterity in 2004’s infamous Some Kind Of Monster, an act of shared self-flagellation masquerading as a making-of documentary film.

Coming after St. Anger, Death Magnetic – all too accurately reappraised in The New Yorker as “a record with all the defeated energy of a sinking stone” – couldn’t help but constitute a rebirth of sorts, and despite the fact that its songs sounded so wrenched out. Hardwired… was stronger yet, a re-flexing of muscles and with a renewed sense of purpose. It’s the Metallica record Ulrich is drawn back to the most – “The one with the longest shelf life for me,” he says. “Or, from a different position, the one I find the fewest faults with.”

72 Seasons ups the ante. Clocking in at a hefty 12 songs/77 minutes, it ranges across four sides of vinyl. It does the same chrome-plated renovation job on the core elements of the classic mid-to-late-80s Metallica sound – the chugga-chugga riffs, Ulrich’s volleying drums, Hammett’s wah-wah-ing solos, Hetfield’s anguished howl – as its two immediate predecessors, but better. Thrilling even at its peak points, and in sum dense, complex and relentless.

On the one hand it’s precision designed to super-serve the diehard Metallica fan. Equally, though, it will delight anyone lured in by the Stranger Things turn. Although, just as much as Master Of Puppets, it echoes its much less cherished follow-up, …And Justice For All, albeit with Trujillo’s bass being audible. 72 Seasons, too, is a record made up of great parts. The opening, Stuka-bomb-run screech of Lux Aeterna, for example. Or the corkscrewing lurches of Crown Of Barbed Wire. Or the rat-a-tat breakdown of closing track Inamortal, an 11-plus-minute epic.

Urich takes the …Justice… comparison as a compliment, but insists: “We tend not to reference the past all that much when we’re being creative. It’s not so much part of an MO, or master plan, as I think perhaps other people perceive it to be.” Hammett’s appraisal of the new album is more concise.

“I just love the fact it doesn’t have a ballad on it,” he enthuses. “No freaking ballads!”

“The biggest objective for us is trying to be truthful to the moment,” Ulrich continues. “Obviously, when you’ve been on a creative journey for north of forty years there are twists and turns, ups and downs. On the back of the Black album, something that resonated to such a magnitude, one of the battle cries became: ‘Let’s not repeat it!’ Thirty years later, you’ve enough clarity to be able to have a conversation about whether you went too far, too much into uncharted waters.

“What happens is you’re in your wheelhouse and reach a point where you feel it’s too confining, so you break out. After you’ve gone off somewhere else for a while, it’s interesting, but you end up missing your original wheelhouse. You go back to where you came from. That’s the path we’ve been on, constantly looking for something."

He’s not so quick to answer the question of what exactly has made it possible for Metallica to have endured, so indomitably, indestructibly, into their fifth decade. Atypically, he falls silent. The pregnant pause lasts for 13 seconds before he at last begins to concoct an answer. “I guess…” Another pause, this one of four seconds. “…We love what we do, and we love each other. We love how it connects us to other people enough to persevere through all the shit that has come in the way.

“When one of us went missing, in the mental and spiritual sense, there was always enough there to pull him back into the fray. We’ve always gone with the option of sticking it out and finding ways to keep going over severing our ties. Severing would often have been the easier thing to do, but we’ve been prepared to put in the time, work and resources to keep this functioning.”

Hammett answers the same question right off the cuff: “Because we’re stubborn, every single one of us, and we don’t want to let the music, or the legacy, down. It’s too precious and unique to give up. We might not be getting along for six months, but that’s enough motivation for anyone to show up.”

The new album’s title is Hetfield’s, and a reference to the first 18 years of a person’s life. Those moulding, formative years from childhood into young adulthood. Eighteen also happens to be the age at which Hetfield and Ulrich first met. Theirs is an oft-told tale. The former responded to a small ad the latter had placed in a local Bay Area free sheet The Recycler: “Drummer looking for other metal musicians to jam with – Tygers of Pan Tang, Diamond Head, Iron Maiden.”

They were, to be sure, an odd couple. Hetfield, raised in the Los Angeles County city of Downey by devout Christian Scientist parents. His World War II vet father, Virgil, walking out on the family when he was 13. Three years later, losing his mother, Cynthia, to cancer, and after she had refused any medical treatment on religious grounds. To Ulrich, the teenaged Hetfield seemed cripplingly shy, entirely out of step with the world around him.

On his side, Ulrich’s father, Torben, a jazz critic and one-time tennis pro, had moved his only son from their native Denmark to the US when he was 15. He was enrolled as a prodigy at the storied Nick Bolletieri Tennis Academy in South Florida. Afterwards, father and son settled in another LA satellite city, Newport Beach, by which time Lars had ditched tennis for music.

“At eighteen I was very narrow-minded, very inexperienced, but very focused on my purpose,” he says. “That was to make music and to try to connect with other people who were disenfranchised, or outcasts. Hard rock fanatics like me. My outlook was very singular.

“James was the brother I never had. Starting out together, we both found solace in each other. We were so different from each other, but somehow the combination of the two of us became a whole. We filled a void in each other. The songs we were writing then, the shows we were playing, the path we were on was very constricted. Nowadays – and I talk with my two sons about this – what I see with a lot of younger people is that their path is so much wider. Their possibilities are much broader. My trajectory was very different.”

Hammett, who joined in 1983 as the 20-year-old replacement for departing powder keg Dave Mustaine, adds: “As a quick insight, James is a very shy person and bashful. I’m shy and bashful. Lars is shy and not so bashful. That’s the band dynamic and it all started from there. Before we were even Metallica we were four super-angry, insecure, frustrated kids who just had passion and a lot of musical energy needing to be unleashed. Nothing’s really changed in terms of our emotional make-up. We’re survivors as far as I’m concerned.”

Hetfield has declined to do interviews with the rock press for 72 Seasons. In many ways the album does his talking for him. His lyrics for it weigh up the damages inflicted on a troubled son growing up. They navigate almost biblical degrees of torment and inner conflict, as unyielding as scripture. On the dread-filled title track, he rails of ‘staring into black light, permanently midnight’. On Crown Of Barbed Wire of ‘this rusted empire I own’. Too Far Gone finds him citing a litany of miseries: ‘Crawling out my skin… I am desperation… I am isolation… I am agitation.’

Back in September of 2019, Hetfield again checked himself into rehab, for treatment for his alcoholism. Later he stated he’d struggled with being on tour with the band and had not been “caring for myself”. Last summer, and with Metallica returned to the road, he was widely reported to have filed for divorce from Francesca Tomasi, his wife of 25 years and mother to their three children. He remains a study in contrasts: the imperious, unbending frontman waging war with his demons; enigmatic, tormented and unknowable, and perhaps at times as much to his own bandmates as to anyone else.

“I ask myself the question: ‘Who is James to me?’” says Trujillo. “I feel he’s someone who wants to show strength and be that individual that commandeers the ship, but there’s always going to be a battle with James. He can be a real, true brother and stand up for you, appreciate you. Then at other times he can get withdrawn, quiet and subdued. He can be a bit of a mystery, but in his heart Ithink he really strives to be better as a person and as a spiritual being.”

“James is my life partner, one of my best friends,” says Ulrich. “He’s someone I love and respect deeply. Someone who is still capable of blowing my mind with his gift. I’m maybe more in awe of him as a creative force than I’ve ever been.

“He’s probably the person I know best on this planet. Often when we’re talking I’ll know what he’s going to say before he says it. If we’re in a group situation, I’ll know how he’s going to act before he acts. At the same time, he’s also enigmatic to me. He’s all of it and more.”

Since St. Anger, the band have continued to manage their schedule around Hetfield’s needs and principally on his terms. They’ve toured in shorter bursts. As with all compromises, this one appears to have its tension points. “We’re a working band, and I don’t feel we play enough shows,” says Hammett. “Other people in the band have other priorities, other responsibilities and other things in their lives, so we’ve had to come to an agreement and find a balance. If it was up to me I’d be touring six months out of every year, easily.”

On the heels of 72 Seasons, Metallica are undertaking the M72 world tour. Subtitled ‘No Repeat Weekend’, it’s 46 shows in 23 cities and other locations, with the band geared up to play completely different sets on each consecutive night. It kicked off in Amsterdam in April and runs through to late September 2024 in Mexico City, and the itinerary takes in both Thursday and Sunday night headliner slots at the Download festival, the event having been extended to four days to accommodate Metallica’s concept.

As an exercise, the tour is entirely in keeping with more recent band projects such as The Metallica Blacklist, the 2021 covers collection to mark the thirtieth anniversary of the Black album. That brought the disparate likes of Phoebe Bridgers, Miley Cyrus with Elton John, Dave Gahan of Depeche Mode, country superstar Chris Stapleton (all of whom took a crack at Nothing Else Matters), St. Vincent, Royal Blood and Jason Isbell (each rendering a version of Sad but True) into the Metallica tent. In the most basic sense, both it and No Repeat Weekend have the ring of ideas conjured up as means of keeping things fresh and interesting for Metallica themselves first and foremost.

“It’s that same juxtaposition I talked about earlier, wanting to keep doing what’s familiar but at the same time to reinvent the wheel,” says Ulrich. “One of the biggest blessings of being in this band is we’ve carved out a way to be able to do both. In terms of our creativity, it still feels like we’re only scratching the surface, as though we have licence to cover a lot more territory.”

Then again, there is the matter of encroaching age and time’s noose. Of one’s own mortality and wanting to get things done before it’s too late. What Bruce Springsteen, when he was nearing 60, once described as the growing, pressing feeling of having to run hard and fast in a bid to stay ahead of the freight train rushing up the tracks behind him.

“I’m starting to see that, at least a little bit,” Ulrich says, laughing. “Absolutely, with Metallica there’s a sense of: ‘Hurry up and get on with it,’ because we may not have as much time as we once thought. Through a significant part of your life, you’re going: ‘I have more ahead of me than behind me.’ Then you wake up one day and go: ‘Holy shit, I may have more behind me!’

“There’s a part of me that still feels very youthful and almost awkwardly young. Then there’s the other part that feels as if I’ve been doing this for a hundred years. Yes I’m going to be sixty soon, but I feel like all my best years are still going to be ahead of me, except they might not be. I like being productive. My dad, who’s ninety-four now, is writing every day and he has volumes of books still in his head. I know what’s keeping him alive is the fact he’s writing these books.”

“For me,” says Hammett, “the future doesn’t even exist yet so I’m not going to spend my time here worrying about it. What is meant to be will be. Less thinking, more being in the moment. And what’s next for me right now is I’m going for a thirty-minute swim.”

Before Ulrich, too, heads back off into his day, he stresses that he isn’t “a big regret kind of guy”. He wouldn’t be minded to going back in time to change, or unpick, any aspect of Metallica’s long and winding road from then to now, he avows, even if he could.

“I don’t spend a lot of time thinking on those kinds of things,” he says. “The bus accident, of course I regret, and other dark, black things. But I’d rather try and make a better job of tomorrow than fix something from yesterday. Were some of the haircuts and wardrobe choices better than others? Yes. Did I open my big mouth and say a bunch of stupid shit? Absolutely. Hey, you do the best you can along the way, you know?”

Paul Rees been a professional writer and journalist for more than 20 years. He was Editor-in-Chief of the music magazines Q and Kerrang! for a total of 13 years and during that period interviewed everyone from Sir Paul McCartney, Madonna and Bruce Springsteen to Noel Gallagher, Adele and Take That. His work has also been published in the Sunday Times, the Telegraph, the Independent, the Evening Standard, the Sunday Express, Classic Rock, Outdoor Fitness, When Saturday Comes and a range of international periodicals.