Pendragon: the journey to The Jewel

From their days as Zeus Pendragon in the late 70s through sell-out Marquee shows and Reading Festival appearances, this is how Pendragon made their debut full-length album The Jewel

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

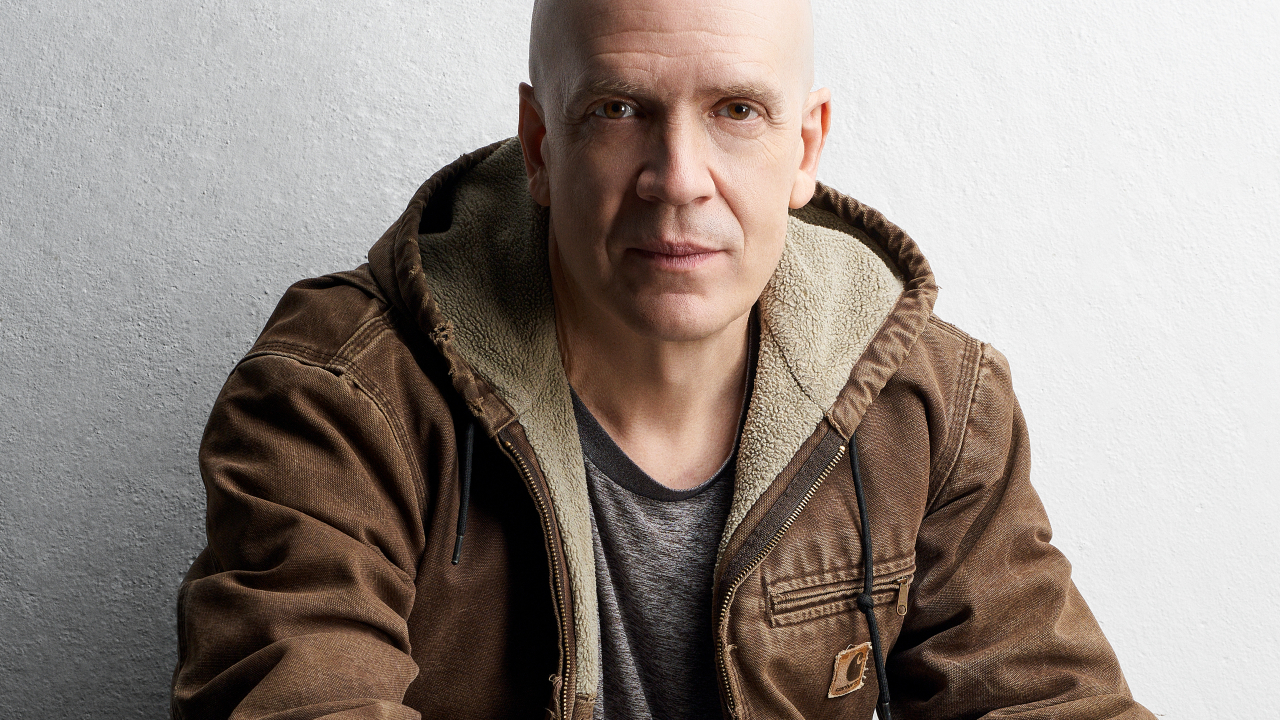

Pendragon vocalist/guitarist Nick Barrett recalls with amusement a line in one particular review of the band’s debut album, The Jewel. “It was described as ‘The equivalent of a dead dog in a ditch’. Well, for a dead dog it didn’t do too badly.”

The story of The Jewel is one of a young band trying to come to terms with the demands of the recording studio, and ending up believing they had failed to make the most of the opportunity. But the story really began when Pendragon came together in Stroud, Gloucestershire, in 1978.

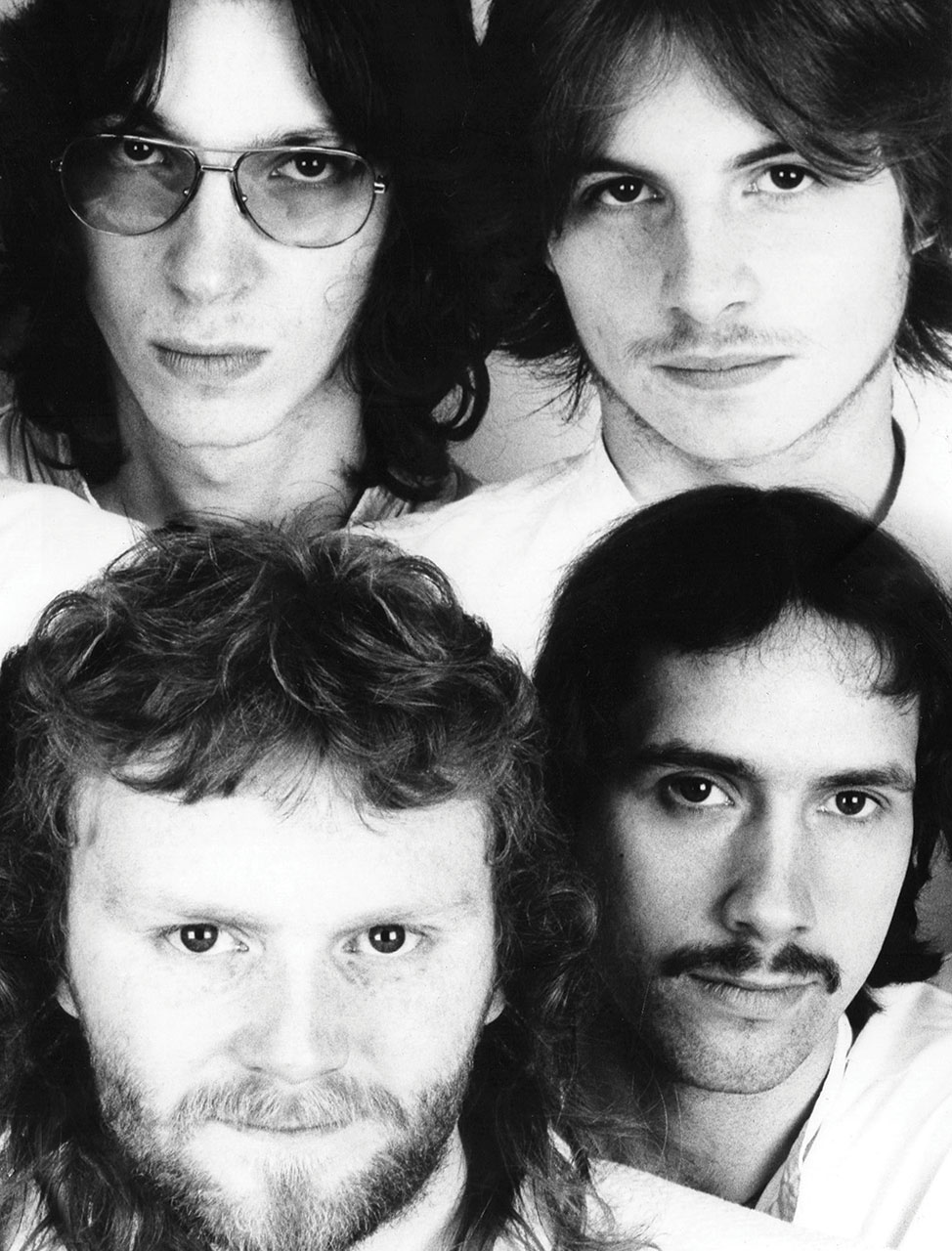

“We were called Zeus Pendragon back then,” says Barrett, “but quickly realised that sounded rubbish, so became Pendragon. At first, we were a covers band doing Hendrix, Led Zeppelin, Bad Company, Free and Santana songs. But then Julian Baker (guitar/vocals) and I got into jazz rock, and we began messing around with complex musical ideas. We were awful, but that kickstarted things, and we then got into songwriting.”

Article continues belowSlowly, Pendragon’s sound took shape, inspired by Genesis, Camel and Pink Floyd. Then, in 1982, they received a major boost. “Our manager, Greg Lines, told us about this young band called Marillion. They sounded like Genesis, but with the Sex Pistols’ aggression. Then Greg, who was also a local promoter, booked them for a gig in Gloucester, with us supporting. It was the shrewdest move anyone ever made on our behalf. We got on so well with Marillion that we did loads of shows with them.”

In August 1983, Pendragon played the Reading Festival. It was a booking that filled Barrett with dread. “I’d gone to the festival in 1976 as a 13-year-old to see Camel, and watched as [early feminist punk band] The Sadista Sisters were bottled off. I was terrified the same thing would happen to us. Thankfully, we went down well.”

Now, all they needed was a record deal. But while other new prog bands were being snapped up, Pendragon were ignored.

“It was so frustrating watching as everyone else got a deal,” admits Barrett. “We had interest, but it never came to anything. I don’t know why. Perhaps it had something to do with our management not being up to the challenge. You can imagine how we felt when Solstice actually turned down a major deal, because they didn’t want to be part of a corporate company!”

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

With a line-up that now included Barrett, keyboard player Rik Carter, bassist Peter Gee and drummer Nigel Harris, Pendragon finally landed their deal, thanks to Marillion’s manager John Arnison.

“John started a label called Elusive, which had a distribution deal through EMI, and we signed with him. The first thing we did was the mini-album Fly High Fall Far, which was put out in 1984. That was co-produced by Pete Hinton and Will Reid Dick. We had no experience at all. Will was a good engineer and Pete was a fine people person, although he wasn’t the right producer for our sort of music. In the end, we had to remix the record, which didn’t go down too well with him.

“The recording sessions were done at Cloud Nine Studios, which was owned by Status Quo’s Rick Parfitt. That excited Peter Gee, because he was a huge Quo fan. Not that Parfitt was around, as he’d just gotten divorced.”

Fly High Fall Far was recorded in just seven days, but it gave the band invaluable experience of being in the studio, something they hoped would stand them in good stead when it came to recording The Jewel. On the surface, everything was in place for this to be a smooth operation.

“We had been playing the material live for so long that we knew exactly how it should sound. But that might have worked a little against us. It might have been better if we’d been less familiar with the tracks, and therefore been more able to let things develop in the studio. But we were convinced that we knew how it

all should come out.”

The band recorded The Jewel at a brand new studio, Sound Mill in Burnham Beach, Berkshire. “It had just been opened by Robin Pryor, who had worked with Twelfth Night as their live sound engineer. His studio wasn’t state-of-the-art, but it was good enough for us, and he gave us a good deal financially.”

However, this time around the band didn’t have a producer to give them that extra guidance.

“The budget wasn’t there for us to bring in an outside producer. Besides, we felt that we could do the job ourselves. That was a mistake. One of the problems was we had three weeks to do the album. That might not seem like a long time now, but it was almost an eternity back then. This meant everything came under the microscope, and suddenly nothing was good enough. We were ultra critical of everything. It got to a point when we could no longer be objective, and heard mistakes all over the place. We really did need someone else in the studio with us, to provide an outside perspective.”

Barrett also recalls that the band members’ different working methods caused extra problems.

“Peter would do his bass parts overnight. So, what would happen was that when I got in during the early morning, to do my vocals and guitar parts, he’d play me back what he’d recorded that night. He was totally fried, though, and when I’d hear what he had done, I knew it wasn’t good enough. So I often told him the bass lines would have be done all over again. It all made the recording process so torturous and difficult. There was a sense of doom in the studio a lot of the time, because we had nobody else to turn to.”

However, there was one outsider who did turn up, and provide a few helpful suggestions.

“Peter had contacted Andy Latimer of Camel and invited him to the studio. Now, none of us expected him to come down. But one day he did. It was just as I was doing the guitar solo for the song The Black Knight, which was a hugely important part of the album. You can imagine how I felt. Here I was trying to get a guitar part right, with my hero staring at me through the glass in the control room. It was really scary.

“But Andy was great to have around. He even came up with a few helpful suggestions on how we might improve one or two things. It’s a shame that we couldn’t have asked him to get more involved, but, as I said, there just wasn’t the money available to bring someone like him on board.”

By the time Pendragon reached the mixing stage for the album, Barrett was too exhausted to play any meaningful role.

“I had been working so hard on my parts that I simply had to bow out, and let Rick and Peter oversee things,” he admits. “The four of us had been quite democratic in the studio. However, I was burnt out by then and had nothing more to offer. In the end we finished the album at 5am on the last day. When we listened back on the sound system in the studio it all came across so well. We really thought we had nailed it. But the trouble was that we didn’t know what sounded good, and what didn’t by this point. It had been such a slog.”

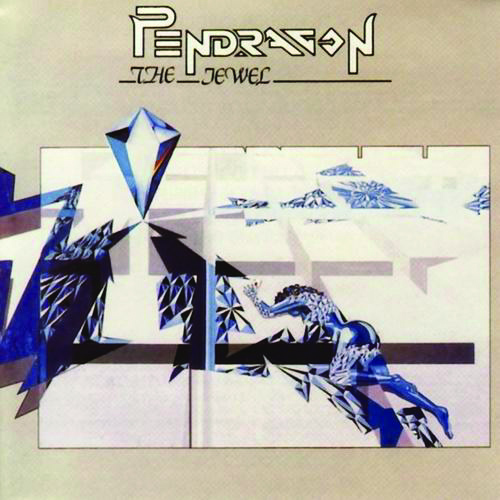

The band always knew they’d call the album The Jewel, and were hands-on when it came to sequencing the tracks. “We wanted to begin with the shorter songs, and then build up to the more complex ones. To us, that seemed to be the best method, and it’s one I’ve used ever since.”

The four band members also took a keen interest in the album artwork.

“The ideas all came from us. Then [sleeve artist] Dave Hancock came up with the design we had on the cover. But we did hit one snag. By this time, Pete Hinton was working in John Arnison’s office, and we told him we’d like a border put on the sleeve artwork. He said, ‘No problem, leave it with me and I’ll get it done’. So, we went back a while later, and he showed us the design with the border. Except that, to us, it appeared as if all Peter had done was get a ruler and Biro pen and draw the border on himself. He insisted the artist had done it professionally. But every time I see that cover, the border just looks like it had been put in with a ruler and Biro in the office!”

The Jewel was released in August 1985, and, despite that “dead dog” comparison, received a generally favourable response, but was slightly hampered by EMI’s lack of interest.

“This wasn’t EMI’s fault,” points out Barrett. “They were only there to distribute it and do limited marketing and promotion.

“But I do recall one person at the company called Norman Bates,” he adds, laughing, “who really did go out of his way to aid us in any way he could. But in the end, it came down to the fact that we needed a better record deal than the one we had.”

Pendragon would spend the next couple of years trying to secure what Barrett calls “the golden record contract”. But they were thwarted at every turn. At one point, a major player at EMI paid for them to record what would become the Kowtow album, with a view to signing them. However, he’d left EMI by the time they’d finished in the studio, and his replacement rejected the album.

“Eventually, in 1988, we set up our own label (Toff) and I discovered that I was actually really good at the business side of things,” says Barrett. “I was able to negotiate distribution deals with different companies around the world. So, we became pioneers in the prog world, and bands like Marillion have followed our example. But this only happened out of sheer desperation. Now, I wish we’d done it for The Jewel. However, at least we now have then rights to this album under our control.”

This article originally appeared in issue 42 of Prog Magazine.

Malcolm Dome had an illustrious and celebrated career which stretched back to working for Record Mirror magazine in the late 70s and Metal Fury in the early 80s before joining Kerrang! at its launch in 1981. His first book, Encyclopedia Metallica, published in 1981, may have been the inspiration for the name of a certain band formed that same year. Dome is also credited with inventing the term "thrash metal" while writing about the Anthrax song Metal Thrashing Mad in 1984. With the launch of Classic Rock magazine in 1998 he became involved with that title, sister magazine Metal Hammer, and was a contributor to Prog magazine since its inception in 2009. He died in 2021.