“Life changed. Time healed wounds. No more feeling alone or depressed – it’s like, ‘Let’s do something positive. Let’s fight’”: When Mariusz Duda escaped the darkness on Lunatic Soul’s Through Shaded Woods

The Riverside leader’s seventh side-project album, intended to be its penultimate release, continued his personal life-and-death story cycle

In 2020 Riverside leader Mariusz Duda released his seventh Lunatic Soul album, Through Shaded Woods. Unlike its predecessors, it featured more brightness than darkness, while it continued a personal story he’d only hint at. But he did reveal his intention that only one more Lunatic Soul record would follow.

All journeys must come to an end, and Mariusz Duda is approaching the conclusion of his own with Lunatic Soul.

“I believe that this is the penultimate album,” says Duda of the project he launched in 2008 and steered in parallel with his higher-profile job as frontman and driving force behind Polish heavyweights Riverside. “It should be eight albums only. I’m not sure if I’ll return to Lunatic Soul after that.”

“This” is Through Shaded Woods, the seventh left turn on a path defined by left turns. Lunatic Soul were conceived as the introspective, inverse reflection of Riverside’s grandstanding modern prog – only to abruptly mutate midway through the last decade into a vehicle for their founder’s lifelong love of electronic music.

It’s another metamorphosis, even more startling than the last. Its six evocative tracks make few concessions to modernity, preferring instead to draw inspiration from nature and Scandinavian and Slavic folklore. It ancient and timeless simultaneously. “I wanted to create dance-in-the-forest songs,” he says, only half joking.

Like pretty much every musician on the planet, he’s been grounded for most of 2020. But he’s used this enforced downtime constructively, releasing a series of spontaneous electronic compositions under his own name via Bandcamp.

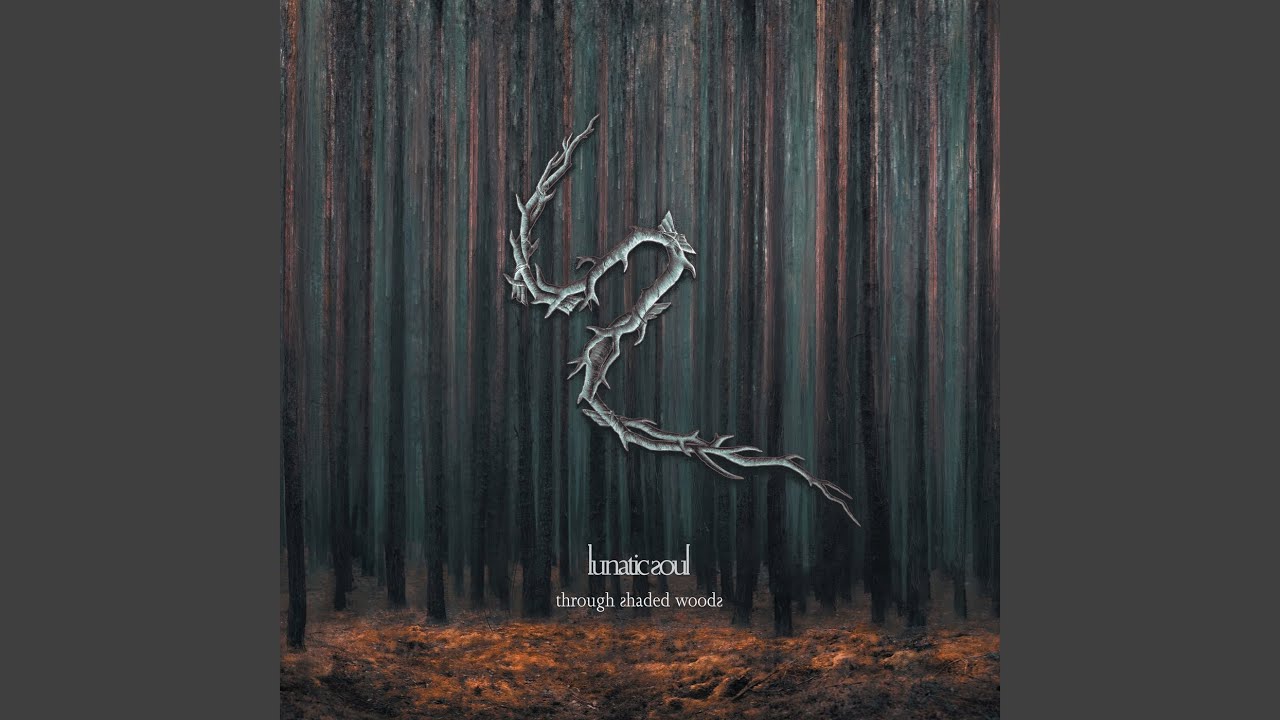

Through Shaded Woods is different. This is far from spontaneous, as illustrated by the relationship between its cover – a photograph of ghostly green trees – and the music. Every LS album sleeve has a different colour: black (Lunatic Soul I), white (LSII), grey (Impressions), blue (Walking On A Flashlight Beam) and red (Fractured and its companion album Under The Fragmented Sky). Putting the aesthetic cart before the horse, he settled on the colour of his next album’s sleeve before he’d even written it. “I decided that it was time for green,” he says. “Green equals ‘forest.’ So I said, ‘Okay, maybe it’s time for this medieval, woodsy, foresty stuff.’”

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

The woods of the title are literal. Duda has lived in Warsaw since 2000, but he spent the first 25 years of his life in Wegorzewo, a small town in northeastern Poland nestled among forests and lakes (“Carefree, calm, quiet, touristy, beautiful, gorgeous,” is his Tripadvisor-worthy summary). It was in those forests that Duda would lose himself as a child, and also as an adult. “I could take a deep breath there when I needed to think of something important. They were the places I could hide.”

The environment that surrounded him dovetailed with the music he listened to. As a kid, he immersed himself in Tangerine Dream and Mike Oldfield, before graduating to the otherworldly chorales of Dead Can Dance, Clannad’s celtic mysticism and Swedish folk changelings Hedningarna. “I really liked this dark folk, with a trance and a pulse,” he says. “It was always somewhere in the shadows, even when I wasn’t writing music that sounded like it.”

Hurting doesn’t mean you should lie on the couch and do nothing. The reward is on the other side of the room

Through Shaded Woods has that same trancelike quality, from the hypnotic rhythms and wordless vocals of Navvie to Summoning Dance’s ritualistic abandon. The title track explicitly evokes the sylvan landscapes of Duda’s youth, right down to the sound of footsteps crunching on leaves that ends it.

But the arboreal imagery is metaphorical too – the woodland of the title refer to what the singer describes as “fighting with your own traumas and fears,” a concept that lies at the core of the album. “I wanted to tell a simple story about hurting, because everybody hurts at some time in their life, and everyone is struggling right now. But hurting doesn’t mean you should just lie on the couch and do nothing. The reward is on the other side of the room. Just get up and go there. Take those first steps.”

It’s not hard to read the theme as a mirror of Duda’s own life. In recent years he’s endured the sudden and unexpected losses of both his father and Riverside bandmate Piotr Grudzinski. But the concept of perseverance in the face of personal pain run deeper and stretch back further. “The whole Lunatic Soul thing came about mostly because I’m a person who suffers, from time to time, with some sort of depression,” he says. “I have these dark moments, these days full of sorrow. Doing these albums is therapy for me. I don’t need pills, I just need music. It’s just a continuation of my story. The Lunatic Soul story – that’s my personal background.”

The protagonist is dying; then he’s wandering in the afterlife. Then he gets the chance to return

When Duda talks about a story, he means it literally. A narrative thread has gradually materialised across the seven LS records. It’s complex and heavy with symbolism; he’s unwilling to lay it out in detail, but it’s there for those who delve deep. “There’s a plot,” he says. “The albums are connected with the circle of life and death. The main protagonist is dying; after he dies he’s wandering somewhere in the afterlife. Then he gets the chance to return, to revive, to go back to life.”

He divides the albums so far into two camps: those on the death side and those on the life side. Lunatic Soul I and II, and the instrumental third album, Impressions, sit in the former category. In the latter are Walking On A Flashlight Beam (“the prequel – about someone who lives, before he crosses to the other side”), Fractured and Under The Fragmented Sky.

There are other clues too: the colour of the sleeves (black, white and grey equal death; blue and red equal life). The ‘snake’ logo is whole on the death albums and shattered on the life albums “because life is broken.” Even the sound of each album is significant: death albums feature organic instruments while life albums have always been electronic.

Through Shaded Woods sits on the ‘death’ side – although it’s far from bleak. “This particular album is about coming back to life,” he says. “It’s the opposite to Walking On A Flashlight Beam. This is about crossing that line, but from death into life. For the first time in Lunatic Soul, I did something that is more bright than dark.”

What changed in his life to prompt the artistic move? “Life changed,” he replies. “Time healed the wounds. I found myself in a new place. I have a new family; no more feeling like I’m alone or depressed. I wanted to do something positive. It’s like, ‘Let’s do something positive – let’s fight.’”

If he’s sticking to his eight-albums-and-out plan, there’s one more to come after Through Shaded Woods. Four albums on the death side, three on the life side. That means the final Lunatic Soul album will be…? “It will be about life chaos and something that forces the protagonist to close himself within. Musically, I will do something crazy.”

Dave Everley has been writing about and occasionally humming along to music since the early 90s. During that time, he has been Deputy Editor on Kerrang! and Classic Rock, Associate Editor on Q magazine and staff writer/tea boy on Raw, not necessarily in that order. He has written for Metal Hammer, Louder, Prog, the Observer, Select, Mojo, the Evening Standard and the totally legendary Ultrakill. He is still waiting for Billy Gibbons to send him a bottle of hot sauce he was promised several years ago.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.