Linkin Park’s Mike Shinoda: “We never wanted to be part of nu metal”

As Linkin Park’s Hybrid Theory turns 20, rapper Mike Shinoda looks back at the birth of their landmark debut album – and how it changed music forever

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

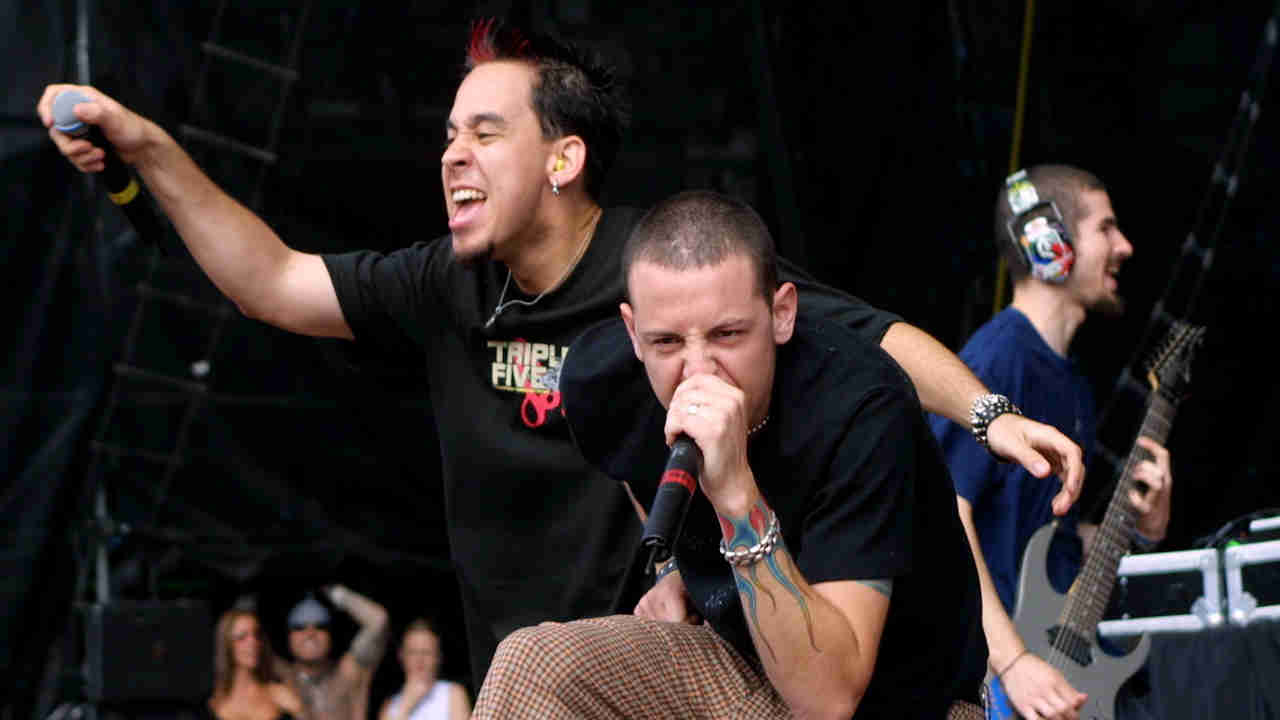

Linkin Park’s Hybrid Theory turns 20 years old on October 24 – where has the time gone? To celebrate the occasion, the band have re-released their landmark debut album along with previously unreleased demos, rarities and B-sides. You can even hear the songs with their previous singer Mark Wakefield, before they changed their name from Xero to Linkin Park, hired Chester Bennington and became one of the biggest rock bands of all time. We caught up with rapper and songwriter Mike Shinoda to talk about 20 years of Hybrid Theory.

- The Chester Bennington I Knew

- The Top 20 best metal albums of 2000

- Revenge of the freaks: the rise, fall and resurrection of nu metal

- Slipknot vs Mushroomhead: revisiting nu metal's most ridiculous feud

Hi Mike, what’s your most vivid memory of making Hybrid Theory?

The process of getting there was so tumultuous and hard. We got turned down by every label and most of the indies as well. [Then] we were basically given the green light to do a demo, which is to say, here’s your album budget and you can start recording and you have to impress everyone. It has to be good enough. As we were getting into that, we were already starting to hand in songs like Crawling. We chose Don Gilmore to produce because he had proven through his recent releases in the last couple of years at that time that he could make a really polished- sounding alternative record. I’m such a technique and gear-related person, I love the craft of getting good sounds. To go in there with every piece of gear that I’ve ever heard of, and start to mic up the drums, get cool guitar sounds and learn how a vocal chain works… it couldn’t have been more exciting.

What was it like being a band on the rise at that time, when there was still loads of money flying about in the music industry and rock was at a commercial peak?

At the time, half of our fans were signed up to be in touch with the band via their home address because they didn’t have email. There wasn’t really a Google. Not only did we not have smart phones, we didn’t have cell phones, we had pagers. No Facebook. No Twitter. No Napster. None of it. We were handing out demos on cassette. It was the very end of cassette and the very beginning of being able to burn CDs at home. That was the time we built our first website and I designed all of the graphics, and we had a message board and a chat room. That was the place for fans to congregate. Our chat room and our message board was vibrant every single day and we were in there talking to people.

What is your favourite memory of Chester from that time?

We started setting up some try-outs and we sent him a tape with three or four instrumentals of songs. We knew he was in the Phoenix area so we expected the fastest he could get it back to us was a week. I think he managed to get it back to us in five days. We got on the phone with him and we were flabbergasted, like, ‘How did you even get this back to us?’ He was like, ‘I got the tape. I heard it. I loved it. I left my own birthday party to go record it and then I sent it immediately. He was ready to get in the car that day and drive out to Los Angeles. That’s the Cliffs Notes version of Chester: this is what I want, I’m going to go and get that thing. He was often open to other things, but his gut reaction to things came quickly and strong.

Sign up below to get the latest from Metal Hammer, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

What was it about Hybrid Theory that resonated so much with people, and why does it continue to resonate?

I guess there’s three things. One, the lyrics being angsty. We were 20ish years old and we wrote lyrics like 20ish old people. There’s an honesty and a rawness to being that old and writing about those things. We didn’t want to write about, ‘Punch you in the face and I’m so mad’. A lot of that stuff was in the ether but we counterbalanced it with introspection and other stuff about ourselves. Second thing, is the blend of genres. At the time, if you asked somebody what they were listening to they’d say, ‘Rock. I listen to hip hop. I listen to jazz.’ It wasn’t until five years later they’d say, ‘Everything’. Hybrid Theory did some of that work. It was part of the progression towards breaking down boundaries between styles of music.”

The third thing is that when you have a song that means something to you at an important moment in time, then it locks in together. I think all those things are the reason. Someone said the other day, ‘Don’t you think if it came out today it would be just as popular?’ and I was like, ‘Oh no!’ It was a moment in time. I also think I’d have a hard time imagining another group that existed at the time, doing what we did. Not to say that somebody else wouldn’t come up with something that moved music some other way, but we were out there touring with everybody.”

Looking back, what was Linkin Park’s contribution to nu metal?

“I never wanted to be part of nu metal. There was a moment when that term, and what it meant, was actually pretty cool. It’s almost impossible to imagine! I remember when Korn first came out and when Deftones’ first couple of albums came out, and whatever you think about a group like Limp Bizkit, their first album was really raw. There were all these groups like Snot and Hed PE, and it wasn’t smart music, but there was something really visceral and culture blending that was important. I listened to 90 per cent rap music, then I’d look at a lot of rock bands and I’d be like, ‘There’s something too white’ [about it]. That was one of the things that turned me off, especially hair metal. Hair metal felt like very white music and I was growing up in a very diverse city so I didn’t gravitate to it. That didn’t resonate with me. And it wasn’t just about race. I don’t mean the colour of skin. I just mean the culture of it. When nu metal started at the very beginning, it was a very diverse place.”

In The End was the moment things really began blow up for you guys. What do you remember about recording that song?

“Originally we were in a really horrible rehearsal space in West Hollywood at Hollywood and Vine. Today there’s fancy restaurants there but back then it was prostitutes and drug dealers. I decided to lock myself in there and just write and I came out with In The End. From the moment that demo arrived, everyone knew it was special. Even Chester. He was such an entertainer, in an interview he might say something that he felt would get a good reaction out of you. You’ll hear him say everything from, ‘I like the song but I never wanted it to be a single’, to ‘I hated the song’. He’s on record with all those different things. Everyone liked the song but he had reservations about it being a single because it was softer. All of us were so confident, we moved about singles to converge. We did One Step Closer and Crawling worldwide, then we added Papercut just in Europe, so we could time it out and we could do In The End as one push at the end of the record.”

What do you hear when you listen back to Hybrid Theory, as someone involved in the process?

“What I really like about this release is the general tone has been a positive and warm nostalgia. That’s certainly what I hoped for because when I listen to it, mostly because of the Hybrid Theory box set package, I hear all of the stuff that was there before the album was done, all the demos, us playing with our friend Mark [Wakefield, original singer] before we met Chester. The different versions of songs. Getting Mark to agree to put his songs on here was one of the biggest challenges! I was really nervous about that because I really wanted them to be out there, and in this way. I think of me recording in my parent’s house, in my bedroom, I didn’t even have racks for the music gear, it just sat in the closet, and then I just opened the door to the closet and scooted up to the corner with an £100 dollar microphone and a cassette four track, just trying to figure out how to make a song.”

Does it feel bittersweet to look back on your journey, given what you have been through following Chester’s death?

“I don’t want that to taint the positive experience of what this is. Why not just let yourself be immersed in this time warp? There are people with tattoos of this time period and art on their body and for me, it’s all about that stuff, all about the moment in time and just letting it run into you. If you watch the DVD that’s included in this thing, it’s over an hour of footage from back then. I watch it and I’m laughing the whole time, we’re just kids running around being idiots.”

Danniii Leivers writes for Classic Rock, Metal Hammer, Prog, The Guardian, NME, Alternative Press, Rock Sound, The Line Of Best Fit and more. She loves the 90s, and is happy where the sea is bluest.