Revenge of the freaks: the rise, fall and resurrection of nu metal

Thanks to Korn, Limp Bizkit and Slipknot, nu metal was the sound of the late 90s. Fred Durst and Coal Chamber’s Dez Fafara look back at how the lunatics took over the asylum

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

On October 27, 1995, a rising band from Bakersfield, California, played their first British gig at London’s LA2 club. Their self-titled debut album had caused a minor stir among the country’s more clued-up rock fans, 800 of whom were here tonight.

The band’s name was Korn, and if they weren’t an entirely unknown quantity, then they were certainly dark horses. Quite literally in the case of singer Jonathan Davis, a former mortuary assistant who whispered, gibbered and shrieked his way through a set of songs about insecurity, twisted sexuality and child abuse.

Korn sounded like little that had come before. They took the pumped up rap-metal of Faith No More, Rage Against The Machine and the Red Hot Chili Peppers and twisted it into unrecognisable shapes. Guitars were downtuned, lyrics were painted several shades of nasty, and they even busted out a set of bagpipes at one point during their set.

Article continues belowFor the 800 people in the LA2, this was the sound of tomorrow. Within two, the scene Korn had spearheaded would be the biggest noise in rock. The bands that came in their wake were an unholy collection of misfits, weirdoes and dead animal-huffing madmen.

This movement would soon be branded nu-metal. It was the sound of the lunatics taking over the asylum.

Los Angeles was dead in the early 90s. Hair metal had gasped its last, Aquanet-choked breath, and the snooty grunge hipsters who had stepped into the breach wouldn’t be seen dead on the Sunset Strip. Instead it was left to a bunch of local bands to build something from the ground up.

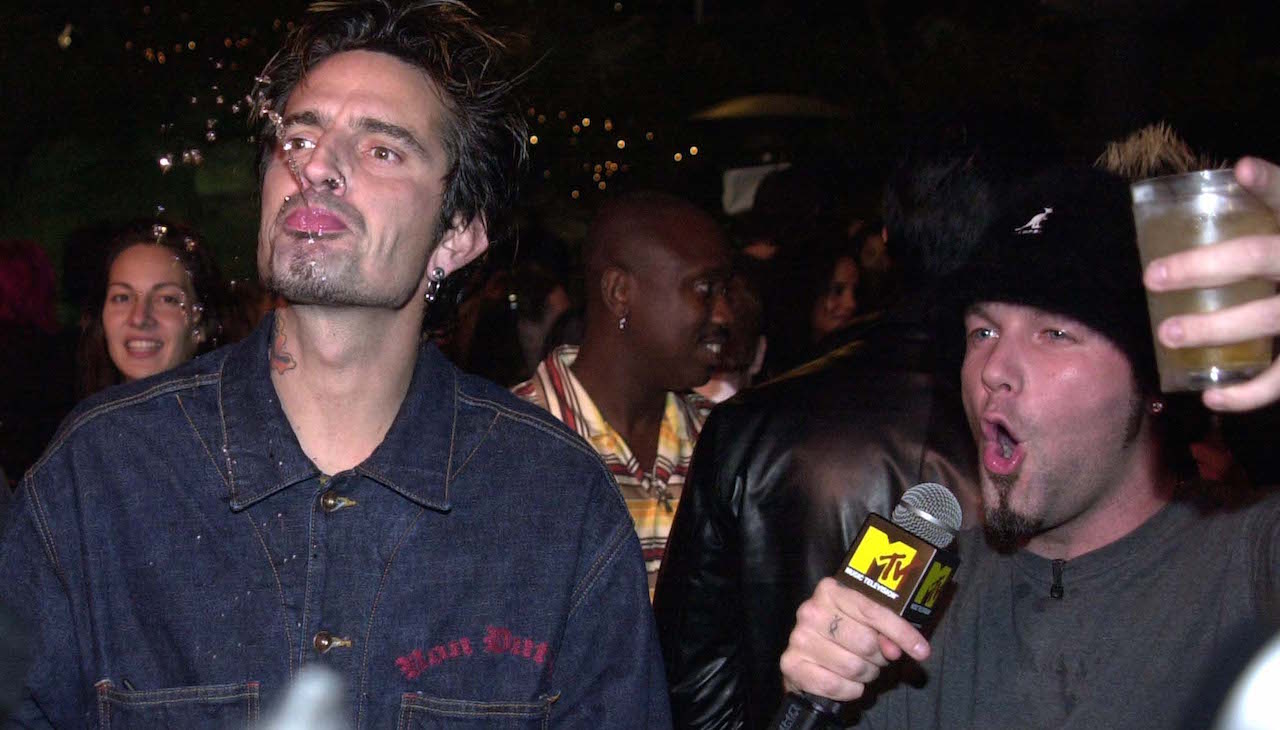

One of these bands was Coal Chamber, whose singer Dez Fafara – son of former child actor Tiger Fafara – was a fan of punk rock and 80s synth-pop. When Fafara started Coal Chamber in 1994, they played standard-issue alt-rock. It was only when they decided to down-tune their guitars that they noticed other bands doing a similar thing.

Sign up below to get the latest from Metal Hammer, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

“In ’92 or ’93, the clubs weren’t happening, nobody was playing them,” says Dez. “But then you started seeing all these bands creeping into these places – Coal Chamber, Deftones, System Of A Down.

Korn would bring busloads of people up from Orange County. The thing is, everybody had to sound different and look different to stand out. We went from wearing Dickies and having our hair braided to getting way more in touch with our goth side. That’s why we dressed so crazy.”

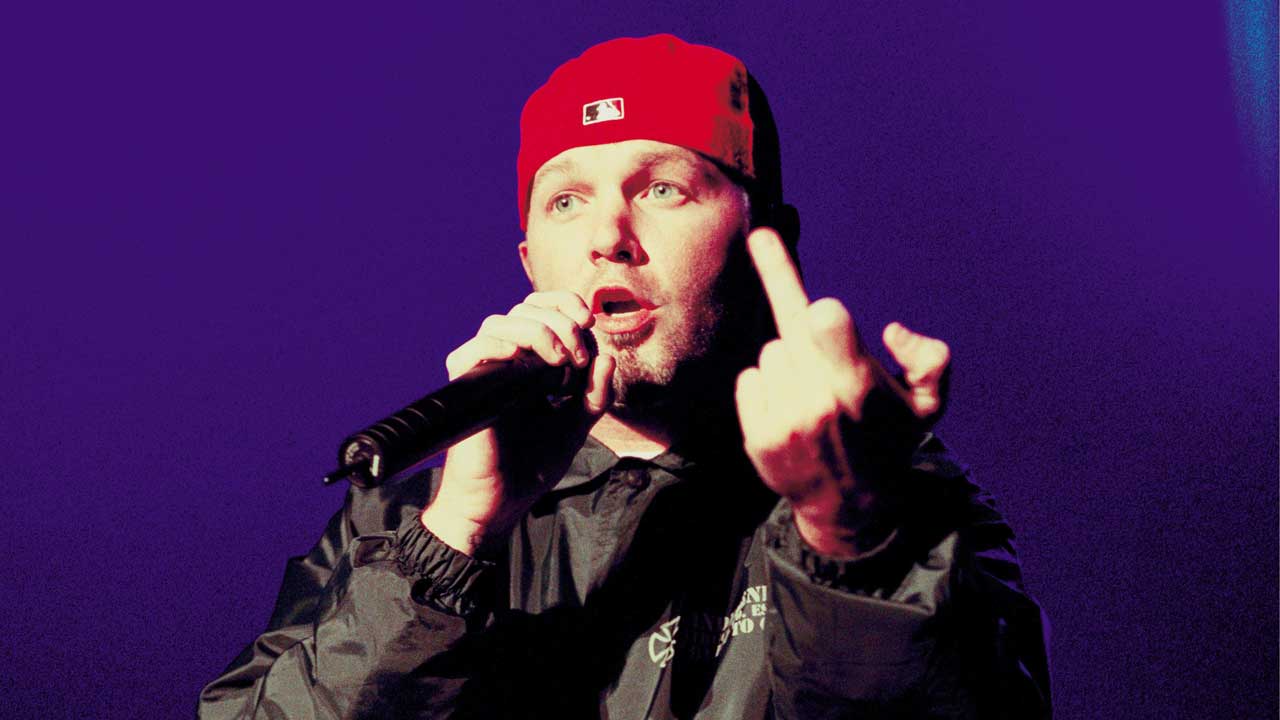

At the same time, something was stirring down in the swamps of Florida. Fronted by sometime tattoo artist Fred Durst, Limp Bizkit were creating waves in their hometown of Jacksonville. More explicitly indebted to hip hop than most of the bands in California, their singer nevertheless wore his outsider status on his sleeve.

“We were the black sheep – or the white sheep,” says Durst. “We weren’t quite hip hop, we weren’t quite metal. But we just didn’t give a fuck, and we always tried to say that fairly blatantly. I think that was one of the things that became dislikeable about us.”

Limp Bizkit may have been based 3000 miles from Los Angeles, but they became honorary members of this new fraternity of misfits after Durst pressed his band’s demo into Korn’s hand when the latter band played Jacksonville.

They jumped on board at exactly the right time. The scene was slowly gaining traction: Korn released their debut album in October 1994; Deftones’ debut, Adrenaline, followed exactly a year later.

The whole thing gained further momentum when Sepultura released Roots in early 1996. The track Cutaway featured Korn’s Jonathan Davis and DJ Lethal of the then-unknown Limp Bizkit alongside unwitting scene godfather Mike Patton of Faith No More.

By the time Limp Bizkit released their own debut album, Three Dollar Bill Y’All$, in 1997, things were speeding so fast that it was all Fred Durst could do to hold on to his red baseball cap.

“It just happened,” he says. “We didn’t have time to pay attention. I was literally bullshitting anything to keep the band going. We were laughing every day at the fact that it even existed in the first place.”

Fred might have quickly presented himself as nu-metal’s jock-in-chief, but he insists that underneath the potty-mouthed braggart in the baseball cap was a shy, insecure man still bearing the mental scars of childhood bullying. His band’s burgeoning success was a massive “fuck you” to all those people who had made his life hell.

“They’d ruined my life, and I thought they’d ruined our fans lives as well,” he says. “I really thought that people were identifying where I was coming from – a guy who finally got to stand up and fight back. The irony was that the bullies themselves started to like the music.”

This sense of outsidership – personal and musical – bred camaraderie between the bands.

“Every time Coal Chamber played, I would call System to open for us,” says Dez. “In the early days, before they became popular, Limp Bizkit would stop by and say hi. When Coal Chamber did our first record, Fieldy from Korn came down and loaned [original Coal Chamber bassist] Rayna his gear.”

Nowhere was that gang mentality stronger than on the Ozzfest. Founded in 1996 as a one day festival-cum-mini tour held in three different cities, by the following year it had become a hugely successful traveling circus, and a lightning rod for freaks and weirdoes onstage and off.

“Ozzfest was incredible,” says Dez. “It was the first time the United States had ever seen anything like it. ‘Whaddya mean we can go and see 30 bands?’ Those kids that are heavily into music, who go to school dressed like the bands they were into and probably got shit for it, they were the ones coming to see us. They wanted to feel like they had something of their own. To feel like they belonged to something more powerful then themselves.”

The out-of-the-box success of Ozzfest spawned a rash of similar multi-band tours, most notably Korn’s Family Values extravaganza, which kicked off in 1998. Limp Bizkit played both events, and played a key role in the burgeoning hedonism that marked the start of nu-metal’s imperial phase.

“I’m a guy that couldn’t shake a stick at pretty girls and get them to date me,” says Fred. “I went from that to roomfuls of people who would do anything for me. I definitely tried to enjoy myself as much as I could. There were moments of madness where I just couldn’t believe what was going on.

"I remember one time there were, like, 15 girls bent over and there was this other girl with a bowl of strawberries, putting them in their butts. All of us were watching, going, ‘What the fuck is going on? This shit doesn’t happen outside of Mötley Crüe videos.’”

In the wake of Ozzfest and Family Values, the floodgates broke. Nu-metal became a truly mainstream proposition. Korn’s Follow The Leader and Limp Bizkit’s Significant Other were huge global hits, paving the way for a new wave of bands to ride their coat-tails.

There was Static-X from Chicago, whose singer, the late Wayne Static, sported a hairstyle that resembled the result of a bizarre electrical accident. There was Orgy, a bunch of eyeliner-sporting hair metal refugees who came on like Duran Duran in leather onesies. There was Snot, Human Waste Project, Videodrone, Adema and countless other long forgotten outfits, all with their own ‘crazy’ shtick, all cranking the dial up to ‘weirdo’.

Most unhinged of all were a nine-piece from the backwaters of the American Midwest who wore jumpsuits and horror-store masks, and huffed the fumes of dead birds before they went onstage.

Slipknot were an incredible experience on every level, and they would eventually keep the freak flag flying almost single-handedly throughout the 00s. But even as they were making a name for themselves, the more astute onlookers were starting to notice the writing on the wall.

“It was definitely starting to play itself out,” says Dez. “There was a certain band, and I won’t say which one, who put out a record, and when I heard it, I went, ‘This is it – the scene is dead.’”

It was a nu-metal band who finally drove the stake through the heart of the scene that spawned them. In 2000, Linkin Park released their debut album, Hybrid Theory. It was an instant success, selling 5 million copies in 12 months (sales eventually exceeded 10 million).

Linkin Park sounded like a nu-metal band, but looked like a boy band. They didn’t swear, they didn’t drink, and they certainly didn’t shove strawberries up anybody’s arse.

The downside of its success was that it raised expectations to unrealistic levels, sucking the oxygen out of the room and leaving everyone else gasping for air. A band like Coal Chamber, who looked and sounded like an explosion in a nail factory, stood no chance in this new, hyper-commercial climate.

It didn’t help that the personal and chemical excesses of the past few years were starting to take their toll. Members of Korn and Deftones struggled with drug addiction, as did three quarters of Coal Chamber, who split up following their third album, Dark Days. “The drugs and the money bullshit was tearing us apart,” says Dez.

Limp Bizkit were having their own problems. Their third album, the none-too-subtly titled Chocolate Starfish And The Hotdog Flavored Water, had been a huge mainstream hit in 2000.

But for everyone who loved them, there were 10 people who loathed them – and especially loathed Fred Durst. One of them happened to be their own guitarist, Wes Borland, who quit in 2001, partly out of embarrassment at what the band had become.

“There was a monster out living out there, and he had a red cap on,” admits Fred now. “I was thinking, ‘That guy? Who the fuck is he?’ It was like Tyler Durden from Fight Club.”

It was Limp Bizkit’s disastrous 2003 album, Results May Vary, that single-handedly knocked the bottom out of what was left of the scene. It was a flop, and Limp Bizkit were yesterday’s men. “We went underground,” says Fred simply, though you could argue that the decision had been taken out of their hands.

Over the next few years, nu-metal became a dirty word. Some bands ploughed on regardless (Korn, Limp Bizkit), some bands wisely ducked out (System Of A Down), some reinvented themselves as more straight-ahead rock’n’roll bands (latecomers-to-the-party Papa Roach). Some, such as Slipknot, even managed to remain on an upward trajectory, though they were firmly in the minority.

But then a strange thing happened. The passage of time and a lack of a decent scene for misfits to latch onto conspired to create a nostalgia for nu-metal. The line-up for 2013’s Download festival featured Korn, Slipknot, Limp Bizkit and the reformed Coal Chamber. More recently, newer bands such as Cane Hill wear their nu-metal influences brazenly on their sleeves.

“I look back on it all and I see how fucking significant it is,” says Dez Fafara. “Some of the biggest bands on the planet right now are from that scene – Slipknot, Korn, System Of A Down. They all came from that scene.

"And the reason is that it was so different. The music, the look, the people. There was something in that scene that was real to the core. And we were proud to be part of it.”

Dave Everley has been writing about and occasionally humming along to music since the early 90s. During that time, he has been Deputy Editor on Kerrang! and Classic Rock, Associate Editor on Q magazine and staff writer/tea boy on Raw, not necessarily in that order. He has written for Metal Hammer, Louder, Prog, the Observer, Select, Mojo, the Evening Standard and the totally legendary Ultrakill. He is still waiting for Billy Gibbons to send him a bottle of hot sauce he was promised several years ago.