"Hopefully when I’m gone, there’ll be something that will stay with people, and move them" - Eddie Van Halen

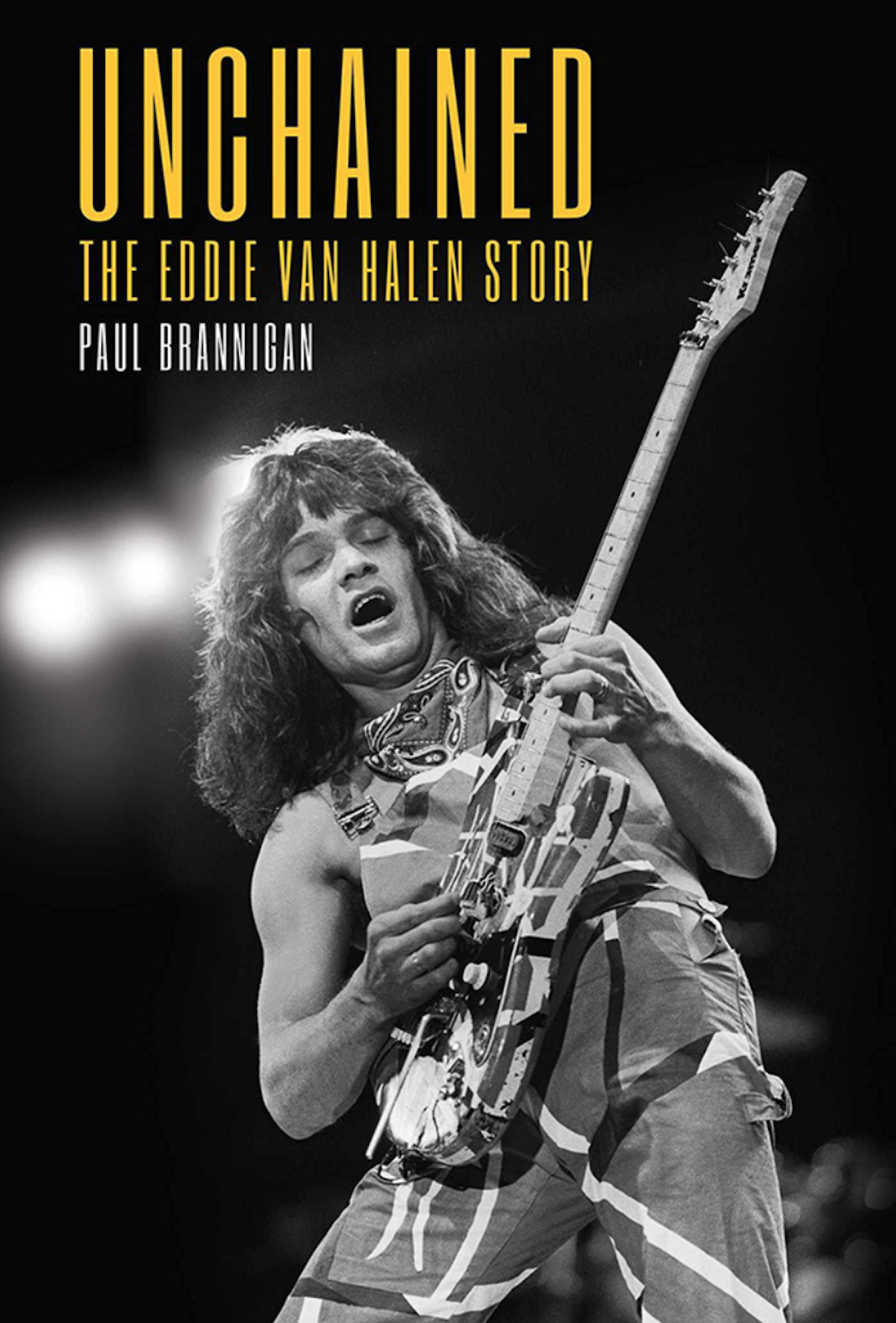

Read the introduction to Classic Rock writer Paul Brannigan’s acclaimed new Eddie Van Halen biography Unchained

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

The acclaimed biography 'Unchained: The Eddie Van Halen Story' by Classic Rock writer Paul Brannigan came out in the UK earlier this year. Now, with a US edition available to order, we're publishing the book's introduction to gave fans a taste of what lies within its pages.

Lost in music, Eddie Van Halen didn’t initially hear his wife screaming at him as he repeatedly pounded out the keyboard riff which had been living rent-free in his head for the best part of two years. Only later, listening back to his first demo recording of that percussive chord vamp, instantly recognisable now as the introduction to his band’s signature anthem Jump, could Eddie pick out the exasperated yells of “Shut up!” coming from the couple’s bedroom as he jabbed staccato triads on the synth on his living-room floor.

In the earliest months of his residency in America, constantly hearing those same two words – from bullying teachers, from racist classmates, from the stressed, exhausted, homesick parents in the two families who shared the three-bedroom property in the Pasadena suburbs in which his own family was housed upon emigrating to California – caused the previously confident, happy-go-lucky, inquisitive Dutch youngster to withdraw deep into his own imagination. It wasn’t until he discovered rock’n’roll, and the liberating potential of an over-amplified electric guitar, that the young Eddie Van Halen found his voice and began to reimagine the world around him.

That process began soon after he reached the age of majority, when, dissatisfied with the mass-produced ‘classic’ guitars that had helped democratise rock ’n’ roll for the generation which preceded him, he invented his own hybrid instrument, a bespoke ‘Frankenstrat’. He then set about creating a whole new vocabulary for this misshapen mongrel as, alongside his elder brother Alex, he negotiated a life in music with the band that bore his surname.

Still he was told to shut up: by club owners who wanted their patrons sedated with familiar pop standards; by buzz-kill cops who’d gatecrash the chaotic, over-subscribed backyard parties Van Halen played every weekend, barking dispersal orders at hundreds of high-school students flipping the bird skywards at the hovering Pasadena Police Department helicopter; even, with increasing regularity, by the needy, limelight-addicted, man-child singer by his side. But the guitarist would be silent no more.

The release of Van Halen’s dazzling self-titled debut album in February 1978 shifted the course of rock ’n’ roll history. As with debut sets from the Jimi Hendrix Experience, Led Zeppelin, Black Sabbath, Ramones, Public Enemy and N.W.A., it created a fresh, original, revitalising blueprint for music with attitude.

Let’s be clear: while it emerged at a time when disco and new wave had captured the popular imagination, Van Halen didn’t ‘save’ hard rock and heavy metal – no rock fan in 1978 listening to Powerage or Live and Dangerous or Stained Class or Hemispheres or Tokyo Tapes considered the genre on its knees, and the nascent New Wave of British Heavy Metal movement which would propel Iron Maiden and Def Leppard into US arenas within five years owed precisely nothing to the Pasadena party rockers – but Eddie’s innovative, incandescent guitar-playing undoubtedly lit a new fire under the genre.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

And with Eruption, his jaw-dropping 102-second solo showcase, blending laser-guided hammer-ons and pull-offs, blur-speed neo-classical triplets, two-handed legato tapping and gravity-drop whammy-bar plunges, the twenty three-year-old guitarist established a new Year Zero for his fellow players. On hearing it, guitarists inevitably had two questions: "How the fuck is he doing that?" and "How can I copy it?"

The most iconic instrumental showcase since Jimi Hendrix’s Woodstock savaging of The Star-Spangled Banner, Eruption served to bisect hard rock’s timeline into ‘Pre-EVH’ and ‘Post-EVH’, creating both a generation of inferior copycat technicians and, arguably of greater significance, a subculture of ‘alternative rock’ guitarists who, awed and daunted by Eddie’s virtuosity, sought to focus instead on fashioning less technical, more individualistic approaches to playing the instrument.

Eddie, of course, had his own influences – early Eric Clapton, Alvin Lee, Jimmy Page, Pete Townshend, Jeff Beck and Allan Holdsworth to name but a few – but in terms of a mindset and modus operandi underpinning his approach to the guitar, it may be instructive to remove any identification with England’s rock aristocracy and, instead, re-centre Eddie spiritually with California’s Z-Boys skateboard crew of the mid-1970s – Tony Alva, Jay Adams, Stacy Peralta, Peggy Oki – fearless, questing, daredevil athletes who constantly pushed boundaries, both physical and psychological.

Like Tony Alva with a wooden deck and polyurethane wheels beneath his feet, Eddie felt at his most weightless with wood and wires in his hands – uncontainable, unstoppable, unchained. As with the Z-Boys launching themselves into empty suburban Californian swimming pools, Eddie’s approach to guitar solos was to leap into the unknown, with no preconceived idea of where, or indeed how, he might land and no fear of the descent.

Like a skater, too, he viewed the bumps and dips of the landscape stretching before him as a space for free expression, and where others saw obstacles, he saw opportunities. "Edward has a sense of adventure," David Lee Roth once noted approvingly. "He will dive headfirst. We’ll see if there’s water in the pool later."

I met Eddie Van Halen only once, at his 5150 studio facility in the grounds of his Los Angeles home, in spring 1998. With its twin-seater SEGA Daytona USA racing game, Twister pinball machine, Asteroids arcade game, widescreen TV and racks of video cassettes and CDs, the studio’s reception room resembled a teenage boy’s idea of an adult male’s home, but the juxtaposition, in the kitchen, of a photograph of Eddie and Alex’s childhood home in Nijmegen, Holland, with a huge, gleaming Recording Industry Association of America presentation plaque acknowledging their group’s 60 million US record sales was a striking reminder of just how far Jan and Eugenia Van Halen’s boys had come.

The man of the house could not have been more gracious or hospitable, proffering non-alcoholic beers before taking a seat on a black couch alongside his band’s new vocalist, former Extreme frontman Gary Cherone, ready to talk up Van Halen’s third act, which was being heralded by the St Patrick’s Day release of the quartet’s eleventh studio album, Van Halen III. He spoke about his love for his six-year-old son Wolfie, telling how the pair would take trips together to the beach to collect stones to fashion into plectrums, and shared his regret at the demands of his job taking him away from his actress wife, Valerie Bertinelli.

Speaking of his pressing need for a hip replacement operation, he noted, "I’m just a fucking old jerk like anyone else." But when he picked up one of his signature series guitars and began tapping out the riff to Drop Dead Legs on the fretboard, his well-lined face seemed to shed the wear and tear of the past fifteen years in an instant.

Over the course of the next hour, as he shared war stories from his twenty-five years in the rock’n’roll business, that guitar never left his hands. It sang, it roared, it squealed, it grumbled, it spat, and often it seemed to laugh aloud, with Eddie smiling and laughing too, seemingly scarcely able to believe the sounds he was making.

Notoriously wary of journalists – "No one really understands what I’m trying to say," he once complained to Guitar Player magazine’s Jas Obrecht, the writer who conducted Eddie’s very first media interview in 1978 and became a trusted confidante – he placed his own Dictaphone on the table alongside mine as our interview began.

It was only years later, as I read more about his working methods, that I realised that his tape recorder wasn’t rolling to ensure that his words would not be misquoted in a publication he would surely never read, but rather to capture the riffs and musical motifs which streamed unselfconsciously from his fingers as he spoke, lest there might be gold buried in the deep.

In conversation with US writer, and avowed fan, Chuck Klosterman for Billboard magazine in 2015, Eddie confessed that he couldn’t recall writing the iconic riffs to any of his band’s biggest songs, having written the vast majority of them while drunk and wired on high-grade cocaine. When he shared with me his belief that, in the past, his excessive drinking was born from a desire to mask the fact that he considered himself ‘the most insecure fuck you’ll ever meet in your life’, it was hard not to wonder whether his tried and trusted methodology of drinking in order to create hadn’t contributed, over the years, to a debilitating sense of imposter syndrome.

Van Halen III, he proudly declared, was the first album he’d written while completely sober. Somewhat cruelly, it was also, inarguably, the worst album ever released under the Van Halen name, and although Eddie spoke that afternoon of ‘making music until I die’, in his remaining twenty-two years on the planet he would never again release a full album of new songs, with Van Halen’s final album, 2012’s A Different Kind of Truth, being largely composed of reworkings of previously unreleased demo tracks originally recorded between 1974 and 1977.

In quiet moments, the indignity must surely have stung the maestro. “There’s an old Russian saying: “There’s no more lines in that guy’s stomach," David Lee Roth told the LA Times in 2012, as A Different Kind of Truth was released. “It means somebody got fat and slow. There are still a lot of lines in Eddie’s stomach.”

Eddie Van Halen’s death, aged sixty-five, on 6 October 2020, elicited a huge outpouring of grief and love from his fellow musicians, many of whom saluted him as ‘the Mozart of the guitar’.

"He was the real deal," said Led Zeppelin’s Jimmy Page, "he pioneered a dazzling technique on guitar with taste and panache that I felt always placed him above his imitators."

"Eddie was a guitar wonder, his playing pure wizardry," said AC/DC’s Angus Young. "To the world of music, he was a special gift." Queen’s Brian May hailed his friend as "probably the most original and dazzling rock guitarist in history", while The Who’s Pete Townshend, another friend, simply called him "the Great American Guitar Player".

Putting the finishing touches to this book in the spring of 2021, six months after Eddie’s death, I dug out the copy of Kerrang! magazine in which my 1998 interview with the guitarist was published. The closing lines of the piece, perhaps inevitably, seemed to carry more gravitas and weight in the wake of his passing. "Music is not a competition," he told me, "and hopefully when I’m gone, there’ll be something that will stay with people, and move them. Whether that’ll be ten people, or ten million people, that’ll be my mission here accomplished."

In the article’s concluding paragraphs, I had referenced the fact that Eddie freely admitted that he had never attempted to keep up with trends in modern music. He had revealed that most recently he’d been listening to Bob Dylan’s thirtieth studio album, 1997’s Time Out of Mind, but that his CD of the album kept sticking on track three.

Now, out of curiosity, I identified the song, Standing in the Doorway, and decided to listen to it as a way of paying my own respects to Eddie. A song about growing old and reflecting on days gone by, it’s written from the perspective of an ageing narrator who smokes, strums a ‘gay guitar’ and recognises that, soon enough, he’ll be meeting once more with the ghosts of his past.

That seems like a fitting elegy for Eddie Van Halen, an artist who’ll forever be enshrined in the collective consciousness standing on a stage, smiling broadly, listening in wonderment to the sounds being conjured from his home-made guitar, hard rock’s own Peter Pan, a free-spirited soul who never grew up but who learned how to fly.

Published by Permuted Press, Unchained: The Eddie Van Halen Story is available to order now from Van Halen Store.

The UK version of the book, titled Eruption, published by Faber and Faber, is on-sale now.

A music writer since 1993, formerly Editor of Kerrang! and Planet Rock magazine (RIP), Paul Brannigan is a Contributing Editor to Louder. Having previously written books on Lemmy, Dave Grohl (the Sunday Times best-seller This Is A Call) and Metallica (Birth School Metallica Death, co-authored with Ian Winwood), his Eddie Van Halen biography (Eruption in the UK, Unchained in the US) emerged in 2021. He has written for Rolling Stone, Mojo and Q, hung out with Fugazi at Dischord House, flown on Ozzy Osbourne's private jet, played Angus Young's Gibson SG, and interviewed everyone from Aerosmith and Beastie Boys to Young Gods and ZZ Top. Born in the North of Ireland, Brannigan lives in North London and supports The Arsenal.