“Robert Fripp is a really diddly-diddly man, all the riff stuff, and that works to an extent. But you need to put that in a context to make it accessible”: The secret to making King Crimson work by Peter Giles, the bassist who helped make it happen

He recalls The Cheerful Insanity Of Giles Giles & Fripp and the Brondesbury Tapes to 21st Century Schizoid Band, making music with his wife and winning athletics medals at 80

Singer and bassist Peter Giles knows a thing or two about going the distance. At 15 years old he swapped winning cross-country championships for playing bass in local groups alongside his drummer brother, Michael. Leaving school the following year, the Giles brothers notched up hundreds of professional gigs and thousands of miles on the road as members of Trendsetters Limited.

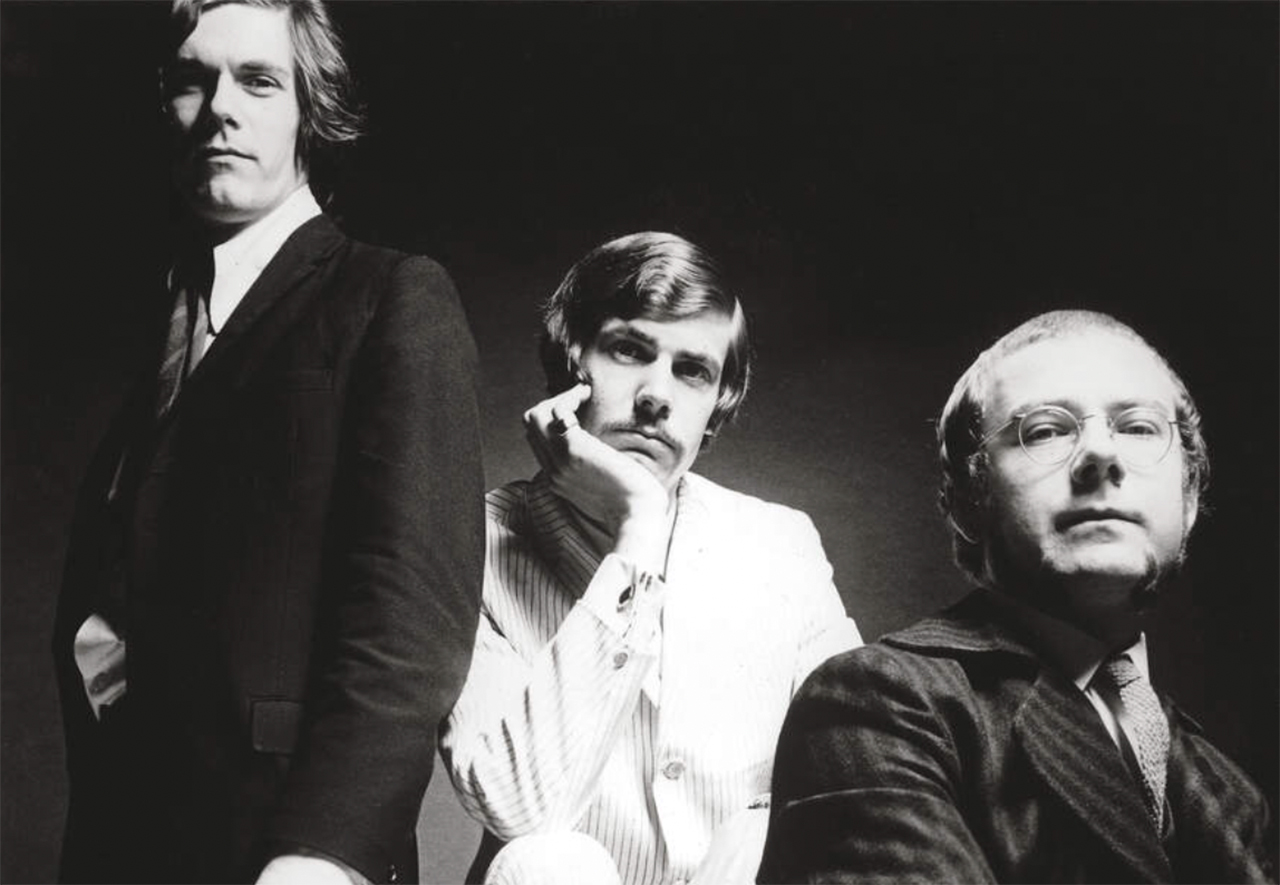

Despite a couple of singles on Parlophone, success eluded them, and they returned to Bournemouth to start anew. When they advertised for a singing organist, Robert Fripp – a local guitarist not known for his prowess at the keyboards or his vocal abilities – came to audition.

“I know, the cheek of the guy!” laughs Giles. “The thing was, we auditioned every piano player and keyboard player we could get our hands on, and they were all fucking useless.” So the unlikely partnership decamped to London and, in 1968, shared a flat in Brondesbury Road, where they recorded high-quality demos in Giles’ home-built studio.

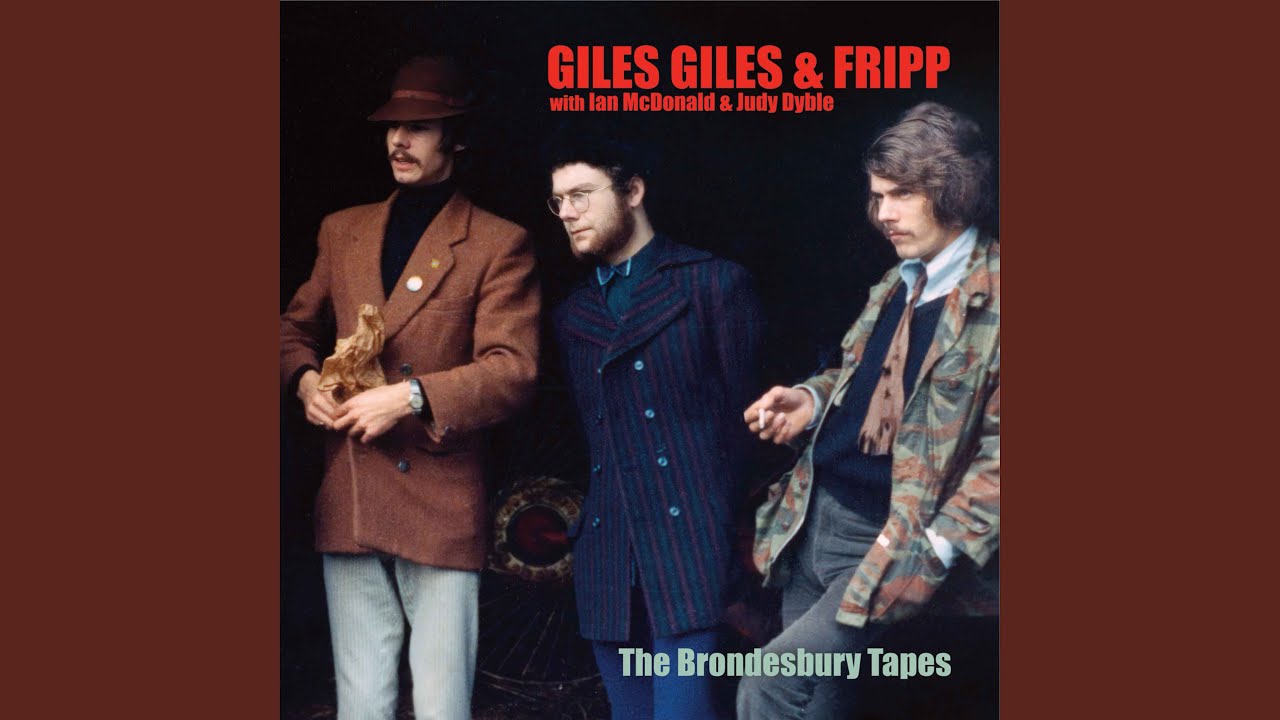

After visiting Decca executive Hugh Mendl in fancy dress “to get their attention,” GG&F were offered a deal on the Deram label. The result was The Cheerful Insanity Of Giles Giles & Fripp – a somewhat whimsical collection of songs, the bulk of which were penned by the Giles brothers, with three pieces from Fripp, all interspersed with frivolous spoken-word interludes.

Although the LP failed to gain momentum and sprint its way into the charts, in the long run it’s become something of a cult favourite among collectors and those curious to explore the origins of King Crimson.

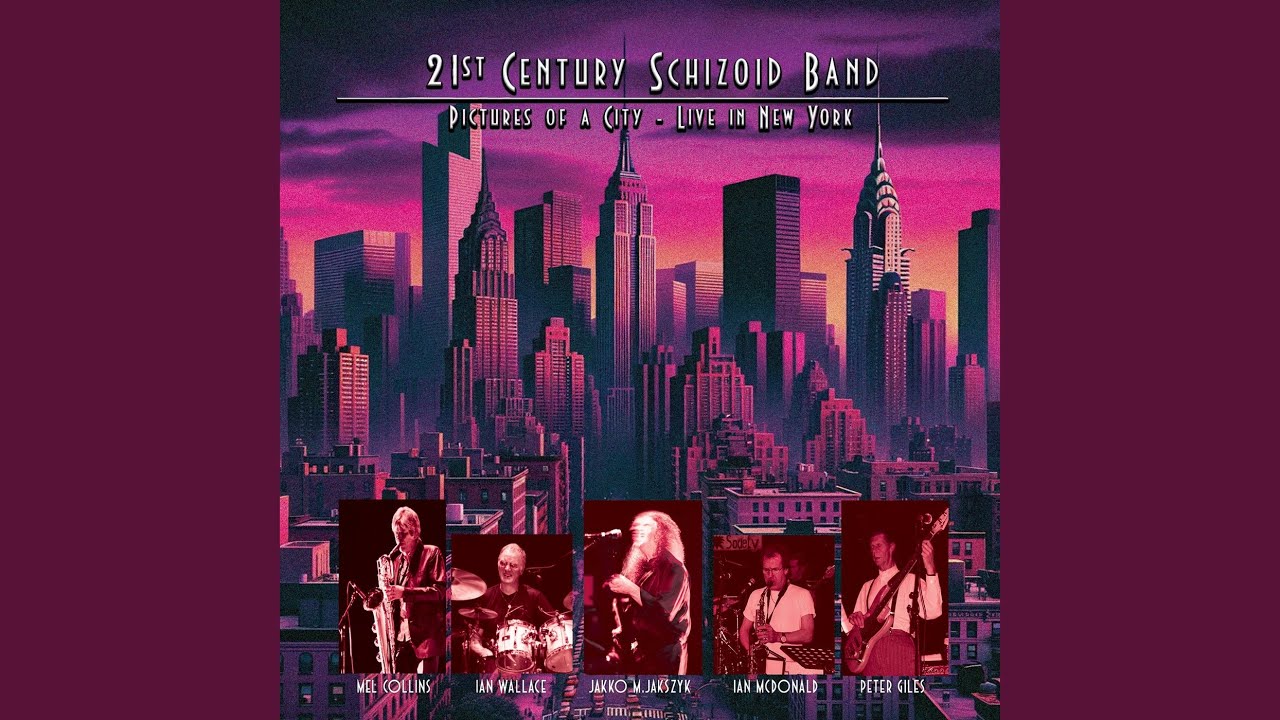

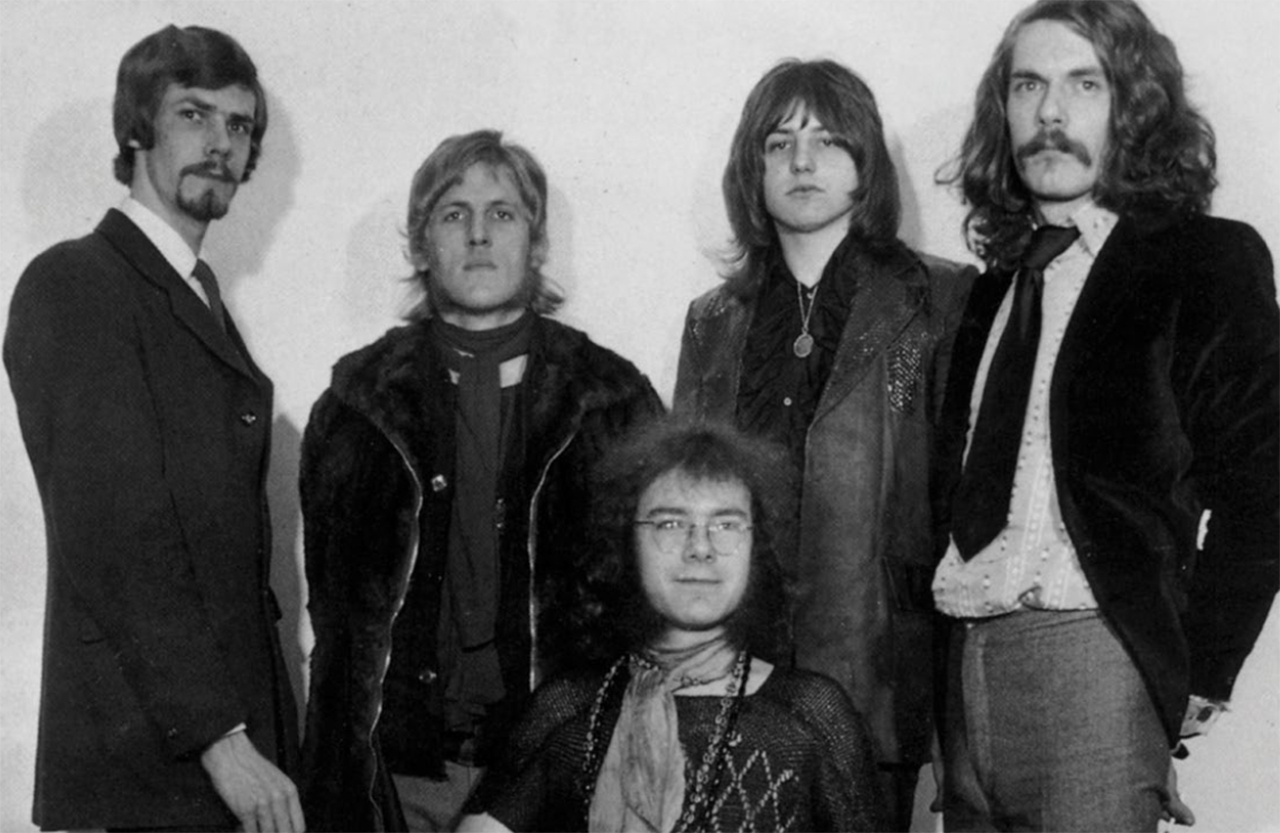

After the dissolution of GG&F at the end of the year, Giles’ distinctive bass appeared on Crimson’s second album In The Wake Of Poseidon; and later that year, on McDonald & Giles, alongside Crimson’s Ian McDonald. In 2002 Giles reunited with brother Michael when he joined the 21st Century Schizoid Band – a venture that included McDonald, Mel Collins, and a pre-Crimson Jakko Jakszyk, who performed King Crimson repertoire released between 1969 and 1974.

The group split up in 2004, and Giles continued to play and perform with his keyboard-playing partner, Yasmine, whom he married in 1988. (“Thirty-seven years and not a cross word,” he says with a smile.) Away from music, Giles has returned to his other passion, running, winning a gold medal at the 2024 World Masters Athletics Championships – at the age of 80. “I won five golds, one silver, and set a British relay record,” he says with some pride. “It’s a real challenge. The same as the music thing was a real challenge, But I succeeded in the running!”

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

What do you recall about how GG&F came into being?

My brother and I were gigging musicians, but we were playing other people’s shit. That’s why we decided to move to London. We put out the advert for a singing organist, but we got fed up with these idiots turning up who couldn’t play.

Then Fripp turned up – here was a guy who could actually play guitar and he had a mate who had a gig in London, so we thought, “Why not?”

What were your first impressions of Fripp?

He had a nice, droll sense of humour, and his chops were really good, his chords and stuff. He was hot. He’d been playing with some older musicians at the Majestic Hotel in Bournemouth, and you learn a lot from those people.

We thought London was the place to be. It’s a lot easier to do it from London than bloody Bournemouth. There wasn’t any wondering about whether we should do it or anything. We stuck everything in my old Daimler Conquest – a huge bloody ballroom of a car – and hiked it up to London.

That was the time of hippies and the emergence of the underground scene. Did you consider yourself part of any counter-culture movement?

We never belonged to anything like that; we were our own people – we were whatever we were. When we went to Decca to speak to Hugh Mendl, ee’d find these funny things to wear from junk shops. Hence the photograph on the front of the LP cover. The blue bow tie I’m wearing was connected to a battery in my pocket. When we were out at night, I’d press the connections and the tie would light up!

What was daily life like in the flat on Brondesbury Road?

My brother was working in the evenings – dinner dance stuff, covering the Top 40. I used to work in the a West End restaurant with an Argentinian guitarist and a blind organist who used to play everything in F-sharp. Fripp was teaching. But Giles Giles & Fripp never did any gigs together.

We were struggling to get the feel we’d got at home. We weren’t happy until we got to final track, Erudite Eyes

Fripp and I used to practise our sight-reading. We used to go to the La Gioconda Café in Denmark Street where all the music publishers were. We’d ask for any old sheet music; we used to get handfuls of this bloody stuff. Fripp read the top line and the chords, and I read the bass parts. We used to spend hours doing that! That’s what we did all day apart from writing and recording.

Did you ever attempt to write any songs together?

Whenever one of us had a song or an idea, the three of us would chip in. My brother is a very good ideas man – melodic, harmonic, and rhythmic. He’s not just a drummer. It never occurred to the three of us to collaborate on writing; we seemed to be quite happy to write our own stuff. It never crossed our minds.

Can you describe the studio you built at Brondesbury Road?

It was essentially a drum booth that enclosed the drums with old carpets and other materials to soundproof them. Then Bob and I sat outside this booth thing and plugged into this metal box with four ports on it. There were no tone controls, just volume controls for each instrument. You’d mix those together onto the tape machine I had.

We were doing things live and then bouncing it down to one channel and overdubbing vocals or whatever. You can’t believe how crude it was – and yet we managed to do these very good recordings. When we were in professional studios, the engineers would say how amazing our tapes sounded; that they were almost of professional studio quality.

How did recording demos at home compare to recording The Cheerful Insanity Of Giles Giles & Fripp?

We were very confident – but we didn’t like Wayne Bickerton, the producer, very much. It was just a lack of chemistry. We were struggling to get the sort of feel we’d got at home. We really weren’t happy at all until we got to final track, Erudite Eyes. That’s when we settled down.

That was Fripp’s composition. He once described it as being “a vehicle, a platform, to get the team up and running, and prepared to take a leap.” It settled us down because at the end of the song, we just carried on. I started farting around and Fripp and my brother followed. It turned out really well. It embodies the spirit as much as anything else. There were some funny and hilarious ones; my brother’s one, The Sun Is Shining, is a complete cod thing. My mother said that was her favourite track!

They let me play whatever I wanted – it was great! I loved Pictures Of A City. I went to town on that one

The album was finished, but then you met Ian McDonald and Judy Dyble, and GG&F started working with them, resulting in demos that were released as The Brondesbury Tapes. How did that come about?

Judy had recently left Fairport Convention and was looking for a bass player for the band that Ian had just joined. He was sort of hanging out with her – I don’t know if they were in a relationship or anything. He’d placed an advert in the Melody Maker. I rang the number, and it was Ian who answered. I told him I’d got a recording set up in Brondesbury Road.

All the things about them wanting a bass player were forgotten because he wasn’t really interested in her band very much – he was much more interested in what I was doing at Brondesbury. He came over and it turned out he was a fucking good guitarist and piano player, saxophone player, and flute player. Give him any bloody thing and he’d get a noise out of it.

He was the melodic guy who put some meat on the bones, such as arranging the vocal harmonies on GG&F’s She Is Loaded. And he was already working with Pete Sinfield, so I brought the two of them into Brondesbury Road.

That’s where you recorded the first version of I Talk To The Wind with Judy on vocals, wasn’t it?

Yes. It was used on A Young Person’s Guide To King Crimson anthology that Fripp put out in 1975. It was really nice – probably the best version of that song. Sometimes things can get a bit stilted in the studio, but that one with Judy was homegrown, and we were very relaxed.

The new edition of The Cheerful Insanity has had all the spoken-word parts removed. Are you upset about that?

Not at all! The producer, David Singleton, asked me what I thought about it, and I said I absolutely agreed. Listening to that album without those parts will be quite novel!

Gustav Holst’s estate wouldn’t give them permission to do a version of Mars. Fripp and Pete Sinfield just had to do best they could

What do you hear when you listen to Cheerful Insanity... and Brondesbury Tapes all these years later?

I hear it with my producer’s hat on. I listen to the song, the harmonic structure and the performance. I just enjoy it on that level – not quite technical because there’s a feeling in there as well. From a musician’s point of view, you’re listening without judging the genre, or asking whether it’s good rock or good this or good that; but just as a piece of music, does it stand up?

After the original King Crimson imploded at the end of 1969, you and Michael ended up on In The Wake Of Poseidon. How did that happen?

Either Fripp or my brother called me up and we started rehearsing in the basement of the café on the Fulham Palace Road where Crimson rehearsed. They let me play whatever the fuck I wanted – it was great! We went into the studio and that was very enjoyable too. I loved Pictures Of A City. I went to town on that one; I was using a Rickenbacker bass with a plectrum.

The improvisation on side two, The Devil’s Triangle, was a fuck-up because Gustav Holst’s estate wouldn’t give them permission to do their version of Mars, which they’d done live. My brother and I had already done the backing tracks for it, so Fripp and Sinfield just had to sort of cock it up as best they could.

The funny thing was that the second album got higher in the charts than the first album at the time, although the first Crimson album sold much better over the longer term. To my mind, the first two Crimson albums were mainly down to Ian McDonald. Fripp is a really diddly-diddly man, all the riff stuff, and that works to an extent. But you need to put that in a context to make it more accessible to people, which is what Ian could do.

You also ended up performing on Top Of The Pops with Michael, Keith Tippett, Greg Lake, and Robert, all miming to the single edit of Cat Food. What do you remember about that experience?

One guy was so emotionally moved by what he’d heard, he was crying. I said, ‘We weren’t that bad, surely?’

We got £25 each! I borrowed a green baize jacket, which I liked, from a friend. I remember being surprised at the way Fripp and Greg were endlessly preening themselves in the dressing room mirror. They’d never done that before. I probably didn’t even bother to comb my hair! Cat Food would have stood a better chance without Keith Tippett’s piano.

The 21st Century Schizoid Band was a dream come true for Crimson fans. What was that like for you?

We all met on neutral territory, had a jam, and then it happened; and we were touring around the world for two years. We got a good reaction and did fantastically well on the merch, meeting fans and signing stuff afterwards. I did notice that when we played in the UK, it was usually to a sea of bald heads, older guys; whereas abroad, they tended to be a much younger crowd. I recall one guy from the UK who came up, and he was so emotionally moved by what he’d heard he was crying. I said, “We weren’t that bad, surely?!”

In a weird case of history repeating itself, your brother abruptly left the group at the end of the band’s first year. Why did he go?

It was in Japan; they were all at a drinks party in someone’s room. I wasn’t there because I don’t drink much. During the party, Mike said he didn’t want to do it any more, and that was it. He said that he wanted us to play more original material – but that doesn’t make sense because it was a band playing King Crimson’s music. How were we supposed to play original stuff?

Did you try to talk him out of leaving?

No. I would never do that.

Ian Wallace, the drummer from the Islands era, joined. What was it like working with a new rhythm partner?

Ian was a real pro, a really good player. America went mad for us, like in the B.B. King Blues Club in New York, where we did two gigs. It’s a weird place – a bit like Ronnie Scott’s in London – and after the first show, they threw everyone out for the second show. And by then we were all comfortable with the sound and everything. We put on a really good show; our best one over there. That was released in 2006 as Pictures Of A City – Live In New York.

Was it daunting learning the bass parts for songs that had originally been played by Greg Lake, Gordon Haskell, Boz Burrell and John Wetton?

No. I didn’t necessarily copy what they did. I would have obviously listened to what they did, but if I thought I could do something better, I just got inside it in my own way.

You’ve been releasing music with your wife, Yasmine.

It’s an equal partnership as writers, players and arrangers. We have total artistic control of our output. Just recently, we re-recorded GG&F’s Digging My Lawn. It’s much better than the original.

Mike and I played together for 12 years, and after our apprenticeship of playing everybody else’s rubbish, we wanted to do our own stuff. Mike fulfilled his dream via GG&F and King Crimson, and I’m fulfilling mine with Yasmine. It’s a lot harder to earn a living than it was in those days, but we still continue as artists producing our music without compromise.

Sid's feature articles and reviews have appeared in numerous publications including Prog, Classic Rock, Record Collector, Q, Mojo and Uncut. A full-time freelance writer with hundreds of sleevenotes and essays for both indie and major record labels to his credit, his book, In The Court Of King Crimson, an acclaimed biography of King Crimson, was substantially revised and expanded in 2019 to coincide with the band’s 50th Anniversary. Alongside appearances on radio and TV, he has lectured on jazz and progressive music in the UK and Europe.

A resident of Whitley Bay in north-east England, he spends far too much time posting photographs of LPs he's listening to on Twitter and Facebook.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.