"The stench of success was horrible for a lot of people": Whipping boys of the music press in the 90s, Bush are still fighting back

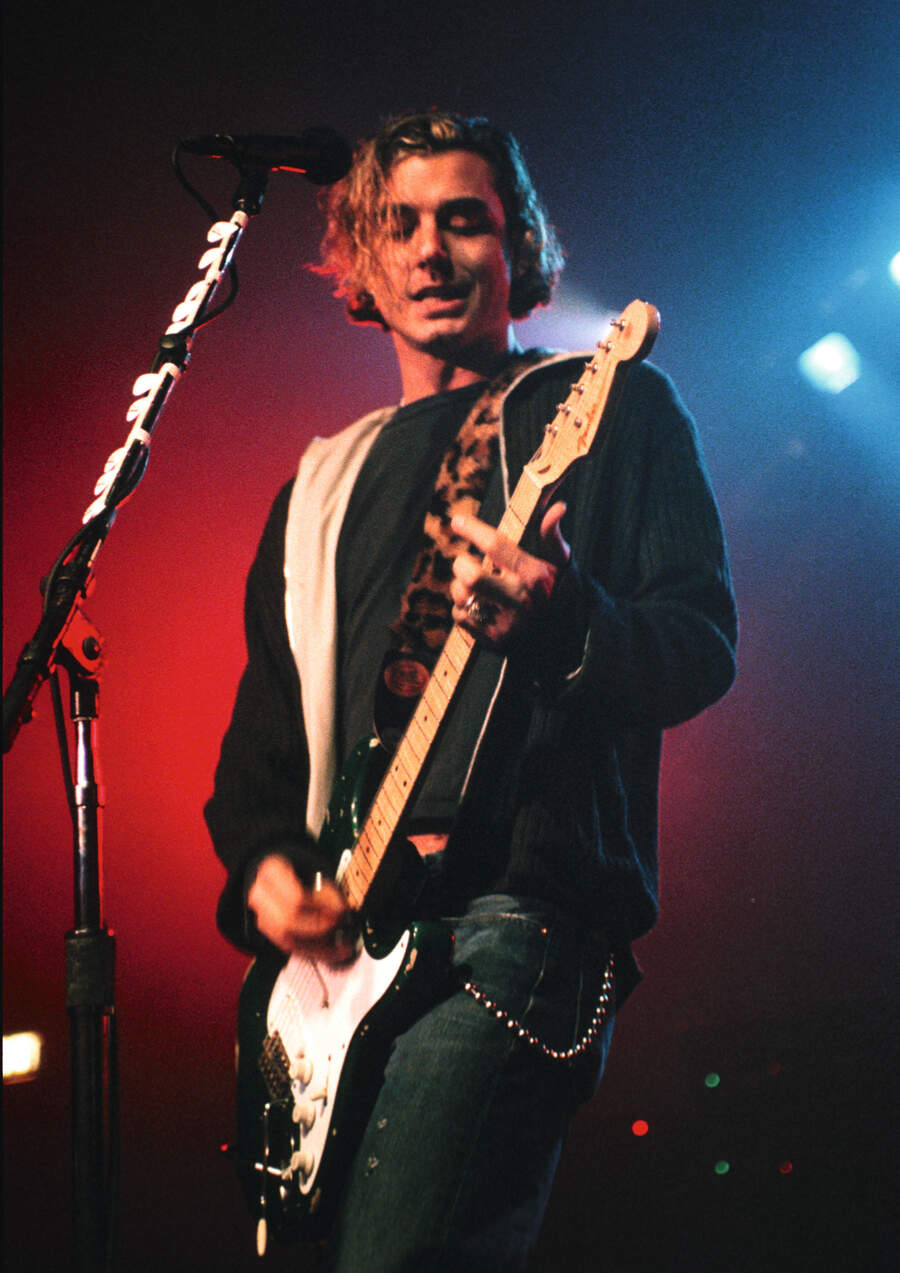

Gavin Rossdale on thirty years of Bush, the mysteries of music making, Steve Albini and the defiance of gravity

Gavin Rossdale has never been able to tune out the critics. For someone whose holy texts as a youth were the weekly UK music papers of the 70s and 80s, with all their gloriously vicious, vituperative opinions, it stung when his own band, Bush, fell prey to those same barbed pens during the band’s dizzying mid-90s rise. Thirty-odd years on, he’s still acutely aware that his music will still be scrutinised. Except these days the judgment comes from closer to home.

“My kids play guitar,” he says. “So I’ve got to deliver records that fucking smack people in the face, cos I don’t want them and their friends to go: ‘Remember when they made those strong early records?’”

Rossdale is talking to Classic Rock via Zoom from Halifax, Nova Scotia on Canada’s Eastern seaboard, where Bush are playing later tonight. It took them a 16-hour bus drive to get here, and Rossdale – as unfailingly polite and impressively handsome as he is - has the air of a man who has spent the best part of a day stuck in a tin can on wheels.

But even the Canadian highway system can’t dent his enthusiasm for music generally and Bush specifically. The band – Rossdale plus guitarist Chris Traynor, bassist Corey Britz and drummer Nik Hughes – have just released I Beat Loneliness, their tenth album. It continues their great six-album run that stretches back to their reunion in 2010, and before that the four they made during their original incarnation between 1992 and 2003.

I Beat Loneliness is sometimes knotty and obtuse, sometimes stark and emotional. It’s undeniably a rock record, but there are electronic touches and stark ballads, with Rossdale’s rich, anguished vocal perpetually at the heart of it. It sounds like the work of a band still in forward motion, even after all this time.

“I should be making mid-tempo, acoustic, dirgy records, with everyone going: ‘Well he did make a couple of decent ones back in the day’, right?” he says. “But these are really intense, vital, ferocious records. I’ve never been able to get too full of myself and just float away, because I’ve never been allowed to. I’ve been forced to fight all the way. Which is no bad thing, by the way.”

It’s odd hearing Rossdale talk about having to “fight all the way”, given his band’s past successes. But the road to this point has been a long one, with slow, grinding struggles uphill and dizzying slides down the other side.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

“I chose a life of pressure,” he says. “I put myself in a position where I was living on a highwire, with nothing to fall back on. I think the only way to make something really valuable is to have nothing - no backup, no safety net.”

The first time I met Rossdale was in July 1995. I’d been sent to cover Bush for an on-the-road piece as they toured the UK. Their debut album, Sixteen Stone, had been released the previous December in the US and lit up almost instantly. Indeed, it had been certified platinum there – one million sales, thank you very much – just a couple of weeks before we met.

It was a different matter in Britain. Sixteen Stone was only now being released in the UK, and the shows they were playing here reflected it: The Garage in London, the Wheatsheaf in Stoke-on-Trent, The Roadhouse in Manchester, the latter a 200-capacity basement bar full of cigarette smoke and beer fumes.

“I remember those gigs,” Rossdale says of the latter. “We’d spent six months in America, playing these big venues where there were stage barriers. Then we get to the Roadhouse and it’s like: ‘Oh shit, what are we going to do here?’”

The Gavin Rossdale of 1995 wasn’t a world away from the Gavin Rossdale of 2025. He was friendly and charming back then, too, even if he was still trying to process his band’s newfound US fame, and already butting up against the accusations of grunge bandwagon-hopping from certain sections of the media that would plague the first act of Bush’s career.

“People call us an overnight success,” he’d said. “What these people don’t realise is that I’ve been doing this for ten years already.”

By that point, Rossdale had been a face on the London music scene since the mid-80s.

“I started in such an ignorant way,” he says. “I wasn’t the kid in the bedroom from eleven to sixteen doing the groundwork. As soon as I started to sing, I was trying to be in a band.”

His biggest shot at success came with the glossy pop-rockers Midnight, who released a couple of singles towards the end of the decade. Photos of Rossdale from the time show him looking like a cross between INXS’s Michael Hutchence and a peripheral member of the court of Louis XIV, and the music matched the image.

“I’d grown up listening to the Sex Pistols,” he says. “The bands I loved were much more primitive. But I wasn’t musically articulate enough to really say what I wanted.”

Neither Midnight nor his next band, The Little Dukes, made more than a ripple. At an impasse, he decided to move to Los Angeles temporarily in an attempt to galvanise his career and his life.

“I felt like I’d got too safe in London” he remembers. “I wanted to experience something different. I put myself in this environment where I was a fish out of water, couch surfing or sleeping in my car on Zuma Beach in Malibu. After that I had a different kind of lust for life.”

When he returned to the UK, he formed Bush, originally named Future Primitive, with guitarist Nigel Pulsford, who he had met at a gig. By that point he’d pretty much let go of any notion of becoming successful, although that was less desperation and more liberation.

“There was complete freedom, and that was reflected more in the music I was making,” he says. “I felt like the bands I’d been in before, they’d made music to tailor it to what people might like. For the first time I was in a band – and this is a fun one for you – I felt like I’d avoided being commercial.”

Bush were unlike any of the bands he’d played with before. It allowed Rossdale and Pulsford to channel their love of the underground music they both loved: Fugazi, Pixies, PJ Harvey. “I thought: ‘Fuck it, at least you’ll be in a cool band that no one has heard of, rather than being in an uncool band that no one has heard of.”

Still, a record deal seemed as far off as it ever was.

“There were two or three years of gigging, playing every club in London,” says Rossdale. “I could name you every A&R man – and it was always men. I could get demo time from every label going. But nobody wanted to sign us.”

Salvation came via Trauma Records, an untested start-up label located in LA’s sprawling suburban San Fernando Valley. It wasn’t a huge deal, but it was a deal.

“It was my one shot,” he says. “People told me not to sign to them. But I just took that chance. Mostly because I didn’t have any other options.”

That one shot paid off. Released in November 1994, Sixteen Stone delivered big, grungy anthems that helped fill the hole left by Kurt Cobain’s death seven months earlier, as well as angular, awkward songs inspired by terrorism and toxic masculinity. But while the US embraced them, back home they were initially ignored, then treated with a mix of suspicion and derision by a music press hung up on Britpop.

“We got so successful so quickly that we pissed a lot of people off. I felt like we were shunned by a lot of people. The stench of success was horrible for a lot of people.”

Sixteen Stone is a far better album than its detractors would admit, and it holds up better than many other records from the same time. But the criticism stung Rossdale, and still does today. The decision to enlist uberhip producer Steve Albini – whose previous clients included Nirvana, The Jesus Lizard and Rossdale’s beloved Pixies – to work on 1996 follow-up Razorblade Suitcase looks in hindsight like an attempt to claw back some credibility and/or head off the critics at the pass.

Razorblade Suitcase was starker and thornier than its predecessor, and it ended up selling three million copies – half of what Sixteen Stone shifted. But for Rossdale, that wasn’t the point.

“To get someone of the stature of Steve Albini to come out and vouch for us and stick up for us and love us and defend us was incredible,” he says of the producer, who died in 2024. “Steve was an incredible person.”

Razorblade Suitcase was Bush’s last commercial big hitter. They released two more albums – 1999’s brilliant but underrated The Science Of Things and 2001’s Golden State – before splitting, tired of the grind and out of place amid nu metal’s frat-bro superstars and garage rock’s thrusting young bucks. In 2005, Rossdale released an album under the name Institute, although it was basically a solo record. An actual solo album, Wanderlust, followed in 2008.

“I did those records cos they [the other Bush guys] didn’t want to come back,” he says. “They’re kind of waste records – a waste of creative energy. I should have carried on doing Bush.”

Bush’s return in 2010 wasn’t hard to see coming. Contemporaries such as the Smashing Pumpkins and Alice In Chains had already reunited successfully, and Rossdale’s band looked ready to surf the growing wave of 90s nostalgia. Easy prey for the cynics and detractors who gave them such a rough ride first time around.

Except that’s not quite what happened. Rossdale and this new iteration of the band – original drummer Robin Goodridge (on board until 2018), guitarist Chris Traynor and bassist Corey Britz – refused to play to the I ❤︎ The 90s crowd. Instead, they delivered a run of albums, starting with 2011’s The Sea Of Memories, that started strong and have grown in intent.

Tellingly, the shit they received 30-odd years ago from the critics is notable by its absence. Maybe it’s because they’re not operating at the same above-the-parapet levels they once were. Maybe it’s because the music press isn’t so pissed off about bands becoming successful without their permission. Or maybe – and this is most likely - people have realised what a great band Bush have always been.

Rossdale likes to joke that “the reviews got better as the sales went down”. It’s a funny line, and not an inaccurate one. But it overlooks how good their albums have been, up to and including the new I Beat Loneliness.

“Music is still really mysterious to me,” he says. “I kind of just put things together. And when I look back on them I couldn’t deconstruct them and do another song like that. I don’t connect to the idea of sitting around and waiting for the fairy dust to hit you at three in the morning. I mean, I don’t mind if the fairy does hit me at three o’clock in the morning and I write something down. But the goal is just to write and wait for the perfect line to drop out.”

One thing that is frustrating about Rossdale is his unwillingness to pull apart the meaning of his songs.

“Words are like a suit of armour for people to feel solace in, or connect to,” he says vaguely at one point. “They’re going to wear them how they want.”

Whether this is a kind of emotional inarticulacy or a deliberate way of obfuscating his feelings isn’t clear, although it seems more like the latter than the former. Case in point: I Beat Loneliness itself, a title that seems pretty on the nose.

“Well, you know it’s one of my best paradoxes,” he begins. “It’s hard to take any paradox seriously. It’s just suggestive. It implies to me someone who’s trying, someone who lives in hope and is always looking on the brightest side of life.”

Should we take I Beat Loneliness literally?

“Well, everyone is absolutely struggling with many things at once, while simultaneously having a really good time and trying to find their way through life,” he says. “I’ve been talking about all of these themes for ever.” He smiles. “But really, it was the first song that I wrote. I thought: ‘That’s a decent title. I’ll keep it until I come up with a better one’. And I never could.”

It’s evasive guff, of course, and he knows it. But Rossdale has an honesty that’s rare in musicians who have been doing it as long as he has. He’s under no illusions that his band are suddenly going to start selling Sixteen Stone numbers again.

“Back then it was a really exciting time, with no horizon,” he says of his band’s mid-90s boom years. “I felt like I was in the running. We were a band on a trajectory. Now, I feel like we’re a really healthy, hard-working rock band.”

But, bus-lag aside, Rossdale seems to have the same kind of drive he had 30-odd years ago. I Beat Loneliness is Bush’s sixth since reuniting, which works out at one every two and a half years. Bands who have been doing it this long aren’t supposed to put out records at that frequency. Then there are the tours (Bush hit the UK this year as support to Danish rockers Volbeat) and the 16-hour bus drives that come with them.

Why is Rossdale still doing this? Perhaps he still has a point to prove. Or maybe he just loves what he’s doing.

“I’ve always sort of defied gravity with this band in the weirdest way,” he says. “I’ve managed to get everything the wrong way round. Some people have these crazy careers, where they don’t have to do too much and it just keeps going. Then you have the middle ground, which is what we’re in – bands who have to work and tour and release albums.

"But the main thing for me is to keep it vital. If it wasn’t vital it would be an awful, hollow existence. I keep doing this because it’s the most fun. I mean, all I’m doing is having a laugh.”

I Beat Loneliness is out now via EarMusic.

Dave Everley has been writing about and occasionally humming along to music since the early 90s. During that time, he has been Deputy Editor on Kerrang! and Classic Rock, Associate Editor on Q magazine and staff writer/tea boy on Raw, not necessarily in that order. He has written for Metal Hammer, Louder, Prog, the Observer, Select, Mojo, the Evening Standard and the totally legendary Ultrakill. He is still waiting for Billy Gibbons to send him a bottle of hot sauce he was promised several years ago.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.