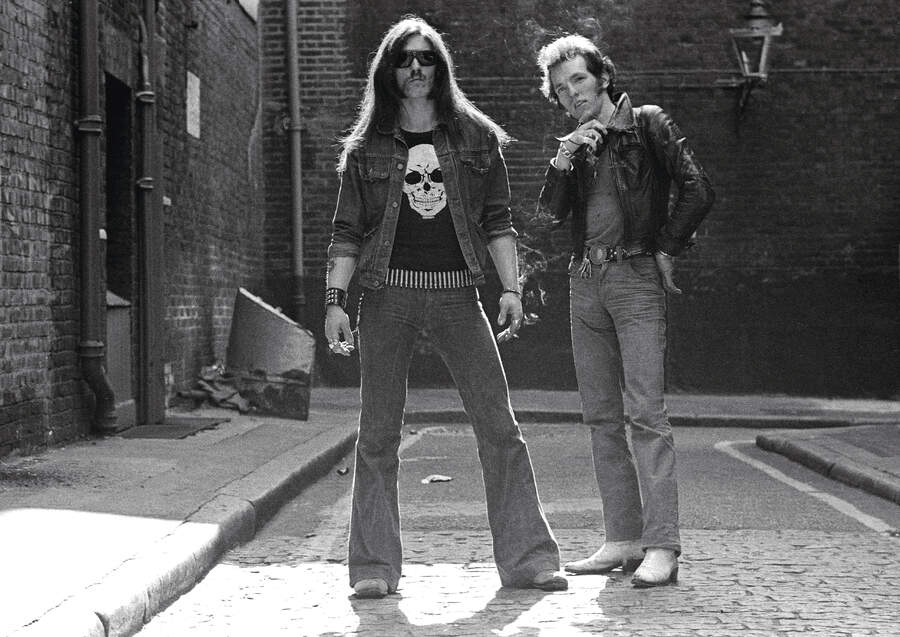

"We wanted Wayne Kramer from The MC5 to be our guitarist": Founding Motörhead drummer Lucas Fox looks back on the band's earliest days

Lucas Fox looked after Lemmy when he was fired by Hawkwind - they bonded over Monty Python, speed and Special Brew

I was introduced to Lemmy by Motorcycle Irene, my good friend, soul buddy and occasional fuck buddy, at the Speakeasy in August 1974. Lemmy was still in Hawkwind, and I was relieved that he didn’t want to talk about spacerock. Instead we chatted about a shared love of The Pretty Things, The Easybeats, The Byrds and The Beatles. We got on like a house on fire from the word go. I had a similar obsession as he did with the Second World War. Both of us loved Monty Python and The Goon Show. I bred horses, and he really liked those too.

I was useful to Lemmy because I had a car. Although he was gregarious, he was a loner, and we were quite happy sitting in silence together while I drove.

Lemmy was more surprised than I was when Hawkwind kicked him out. When he went AWOL after a few days without sleep, their office would call asking if I knew where was. They felt he was unreliable. There was also jealousy. Nobody had wanted him to sing on Hawkwind’s Silver Machine, but he was the only one that could do it. And of course it became a massive hit.

Suddenly the spotlight was on Lemmy and not Dave Brock. Journalists wanted to interview Lemmy because he was funnier. Lem blamed his sacking on ‘taking the wrong drugs’, which was true – he was on speed when everyone else took acid – but there was far more to it. Whenever I was within the Hawkwind circle it was pretty poisonous.

After Hawkwind sacked him, manager Doug Smith asked me to pick up Lemmy from Heathrow on May 14, 1975. I dropped him at Irene’s place, where apparently he downed all of his duty-free booze. The next day he was completely miserable, pissed off and ashamed for trying to get speed through customs in a packet of Beecham’s Powders in his underwear. It was ‘those bastards’ this… and ‘those bastards’ that… So Irene suggested using Bastard as the name of the band that we formed. But we were convinced to change it to Motörhead, the last song that Lemmy had written before Hawkwind kicked him out.

A couple of weeks later, Lem asked me to meet him at the local pub. He took out two Marlborough cigarettes, lit them both, passed one to me, and through a cloud of smoke announced: ‘We are Motörhead and we’re gonna play rock’n’roll’. Saying it for the first time made me realise that we were going to form a band.

Larry Wallis wasn’t our first choice as the guitarist. We preferred Wayne Kramer from the MC5, but three weeks before we contacted Wayne he’d been jailed on cocaine charges. I exchanged emails with him last year just before he died, and he told me that he would have leapt at it.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Like I said, Lemmy was a lone wolf. He didn’t know Larry very well, and there was a lot of ribaldry, trying to put each other down, but right from the start things felt magical. We had eleven days to rehearse for our first gig, at the Roundhouse in London, opening for Greenslade, but sometimes Lem would stay up for days on speed and then crash out, and when that happened you just couldn’t wake him up.

Also, I don’t think Larry had ever really taken speed before. So while Larry was rolling joints, Lem and I supped Special Brew, our tipple at the time, and Southern Comfort, an awful drink that seemed to take the edge off the amphetamines.

We launched out onto the road at the Roundhouse on July 20, 1975, followed by 19 dates. This was an exciting band, riding down the edge of a razor blade every night. When we played the Marquee in London, John Cale from the Velvet Underground asked me to join him, but I was loyal to Lemmy.

We recorded the album On Parole at Rockfield under the auspices of Dave Edmunds. As producer, Dave was shocked by the idea of recording everything live, which is what we all wanted to do. The way Dave had the place mic-ed up there was little or no separation between the drums and the rest of the instruments. There were lots of problems during the recording. So much speed being taken, things went right off the rails. Dave Edmunds was replaced by Fritz Fryer.

I left the band, too, but you could also say that I was booted out. It happened both ways. I was pissed off with them, and they were unhappy with me not being up to scratch. The reason was simple. At Rockfield, some bikers had supplied us with some of the strongest speed imaginable, and in combination with too much drink and a lack of food those horrendous amphetamines ensured that I didn’t perform well enough. I knew that my drumming was a bit too safe, and I had intended to overdub the toms and cymbals to make it sound really accurate, but I didn’t get the chance. That’s when Phil Taylor came in, unbeknown to me, to do the drums overdubs.

On Parole was shelved, and didn’t come out until 1979 – without the band’s permission, and after they had become successful. Andrew Lauder and Martin Davis from United Artists had refused to put it out, and I understand why, because Fritz Fryer’s first mix was terrible. It was muddy and horrible. Lemmy felt the same, though I’d hazard a guess that he’d have been happier with the remastered and expanded edition which came out a few years ago because it sounded like it did in the studio. You can hear both drummers, and I’m credited with playing on loads more tracks. Some are credited to Phil Taylor as ‘overdubbed or additional drums’.

From my side, I never regretted what happened. Motörhead had a spirit of ‘us against the world’, which I loved. Being in that band was in some ways a terrifying experience, but it made me very proud. With the right sound, On Parole would have bridged the gap between garage rock, punk and progressive rock.

Lemmy never did get to go back to Hawkwind, which was what he had wanted all along, but of course he had a great career with Motörhead. Lemmy and I remained very close till I moved to Paris in 1988 and he relocated to LA in the 1990s, but those first 18 months of Motörhead will always be very precious. When Lemmy died, I was surprised by how very, very emotional it made me feel. Just like Keith Richards, you didn’t expect him to go. He had a metabolism that was completely distorted by all of the things he’d put inside of him.

He was a man of many paradoxes.

Lucas Fox’s book Motörhead In And Out is available in French. An English-language edition in the pipeline.

Lucas Fox co-founded Motörhead with Lemmy and Larry Wallace in 1975, and played on their On Parole sessions. He later played in punk band Warsaw Pakt and has performed with The Scientists, The Sisterhood, the Pink Faries and more. A former director of France's popular Midem music industry convention, his autobiography Motörhead In And Out - Entre Autres Histoires D'une Vie Wxubérante was published 2025.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.