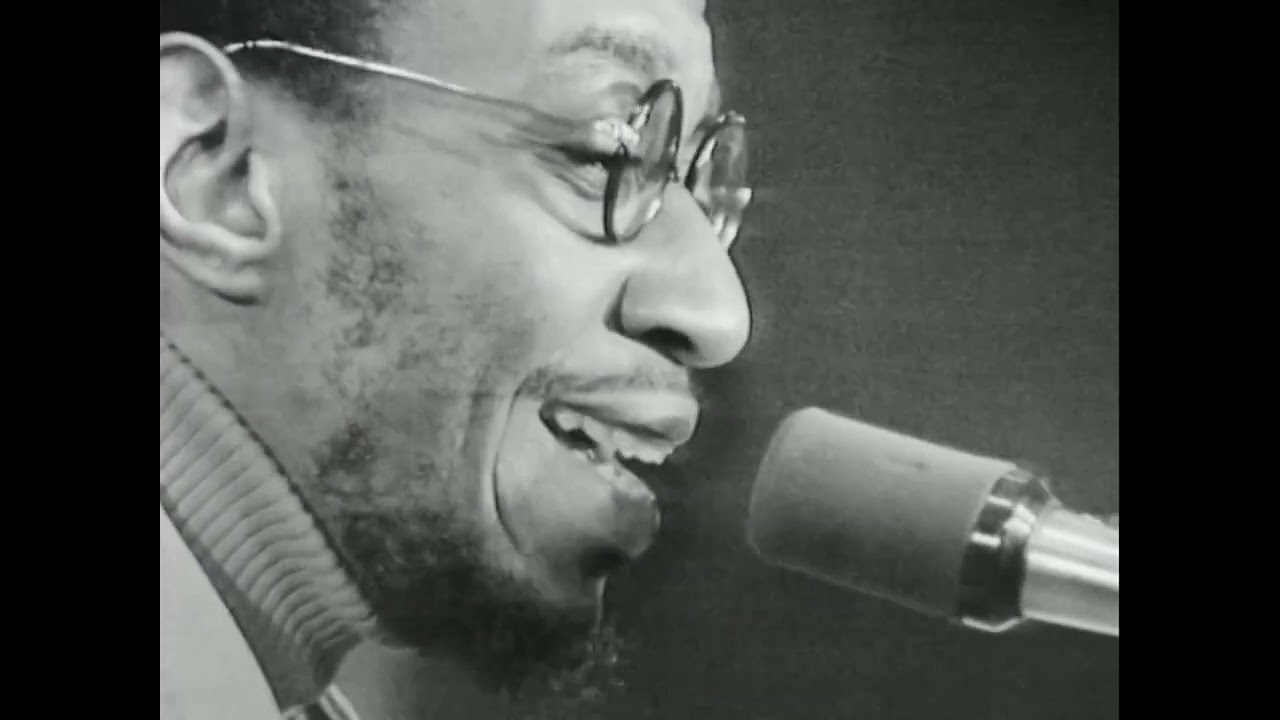

"I did all my research in his home in his record collection": A tribute to John Mayall, November 29, 1933 – July 22, 2024

A look back at the life, music and legacy of the Godfather of British blues, John Mayall

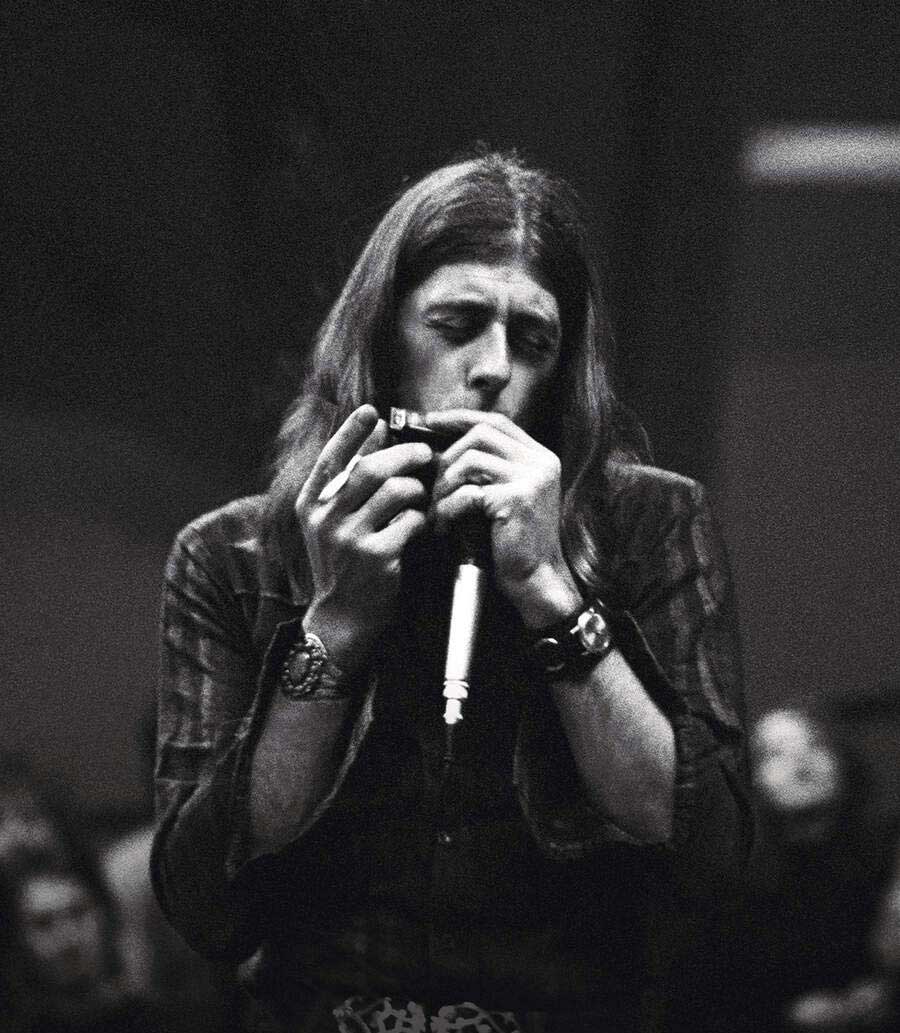

British blues legend John Mayall died at the age of 90 on July 22, 2024. A road warrior and torchbearer for the blues music that he loved all his life, he was for so long invincible and irreducible. As a singer, songwriter, multi-instrumentalist and interpreter of the deep blues repertoire, he was a powerhouse of knowledge and musical passion. As a bandleader, he was a man of exceptional vision and managerial ingenuity who provided an early platform for some of the greatest talents the rock world has known.

Mayall’s 1966 album Blues Breakers With Eric Clapton – aka the Beano album – shaped the sound of modern guitar music and could arguably be called the first ‘rock’ album. Subsequent releases A Hard Road and Crusade introduced Peter Green and Mick Taylor respectively to the international stage, alongside a small army of musicians who gained early recognition thanks to their association in Mayall’s bands, including John McVie, Mick Fleetwood, Andy Fraser, Jack Bruce, Aynsley Dunbar, Jon Hiseman, Dick Heckstall-Smith and, later on, Walter Trout, Coco Montoya, Buddy Whittington and many others.

Although well aware of the impact his music and his stellar choice of musicians had made, Mayall remained pragmatic and humble about his achievements.

“I’m just a man who loves his music and knows what’s out there to listen to,” he told me in 2016. “People comment all the time about: ‘How do you keep getting all these bands together?’ For me it’s a very easy operation. I think it was a lot to do with how familiar I was with the music. I had a much longer start. When I started playing professionally, in 1963, I was already thirty years old, so I’d had a lifetime of listening to American blues music from the age of ten onwards. It wasn’t just Chicago blues, it was all blues, all American blues, that I was exposed to. So it all became part of my musical education.”

This was a fair point. Born in 1933 in Macclesfield, Cheshire, Mayall had been a schoolboy during the Second World War and in 1953 was posted to Korea as part of his national service in the British Army, narrowly avoiding active combat when the war there finished just before he arrived. When he got back from Korea, his father, Murray Mayall, who was a guitarist of local repute, gave him a copy of Big Bill Broonzy’s autobiography, Big Bill Blues, signed by the bluesman himself.

Mayall formed his first serious group, the Powerhouse Four, in 1958 while studying at Manchester College Of Art. By 1962 he was playing in a band called the Blues Syndicate, when he blagged a gig supporting Alexis Korner’s Blues Incorporated – at that time featuring Jack Bruce on bass and Ginger Baker on drums - at the Bodega club in Manchester. Korner became a friend and mentor, encouraging Mayall to move to London, where he helped him make valuable contacts and get himself established on the club circuit.

As well as musical and spiritual inspiration, over the years Mayall took a lot of practical cues from Korner on how to conduct himself in the role of bandleader.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

“To be a good bandleader you have to have a musical concept,” is how Mayall explained it. “You have to have the ears to know what you want from a player. You have to choose players who are compatible on a social level, and you have to be a good organiser. My philosophy for putting a band together is that you must really enjoy what you’re doing and express yourself and have lots of room for experimentation and development for your own musical talent.”

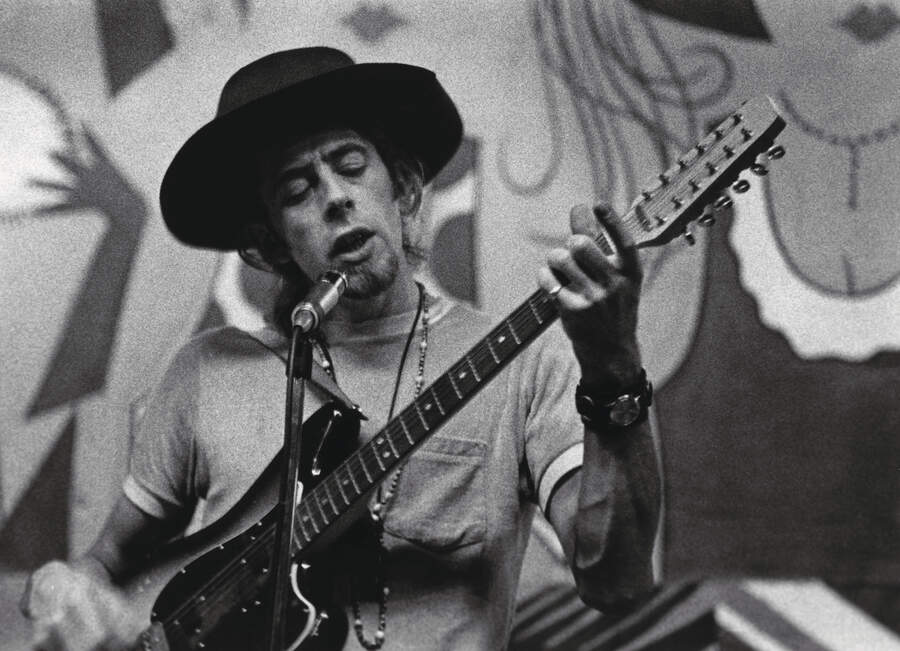

There was also a hard, practical side to his choice of musicians. Mayall was their employer, not just a bandmate. As such he was looking to hire the best people for the job, and his judgements were rarely clouded by sentiment. This explains, in part, why his bands attracted so many great players. He disliked drunken behaviour, for which he fired several musicians over the years, notably, at different times, both John McVie and Mick Fleetwood. And as soon as he felt someone was not fitting in or a line-up had passed its best, he stepped in to make the necessary changes. As far as Mayall was concerned, hiring Eric Clapton in 1965 was a no-brainer.

“I remember hearing Eric playing on a Yardbirds B-Side, Got To Hurry, and I could not believe it,” Mayall recalled. “It blew me away. I just had to have him. It was like an instant soul connection. I called him up and offered him the job. He came down to my house and the deal was done. Twenty pounds a week and off we go.”

Clapton remembers it as £35 a week in his autobiography, published in 2007. “It was a set wage no matter how much work you did,” Clapton recalled. “A not untypical night might involve travelling up to Sheffield to play the evening gig at eight o’clock, then heading off to Manchester to play the all-nighter, followed by driving back to London and being dropped off at Charing Cross station at six in the morning.”

But Mayall was far more than just a bandleader to Clapton, who took a room in Mayall’s family home in Lee Green while he was in the band. “He found me and took me into his home and asked me to join his band,” Clapton said in an emotional statement posted on social media shortly after Mayall’s death. “And I stayed with him and I learned all that I really have to draw on today in terms of technique and desire to play the kind of music that I love to play. I did all my research in his home in his record collection, the Chicago blues that he was such an expert on.” Mick Fleetwood expressed a broadly similar sentiment when he likened Mayall’s death to that of “losing a musical father”. Walter Trout declared: “He is and always will be my musical mentor. I loved him like a father and I always will.”

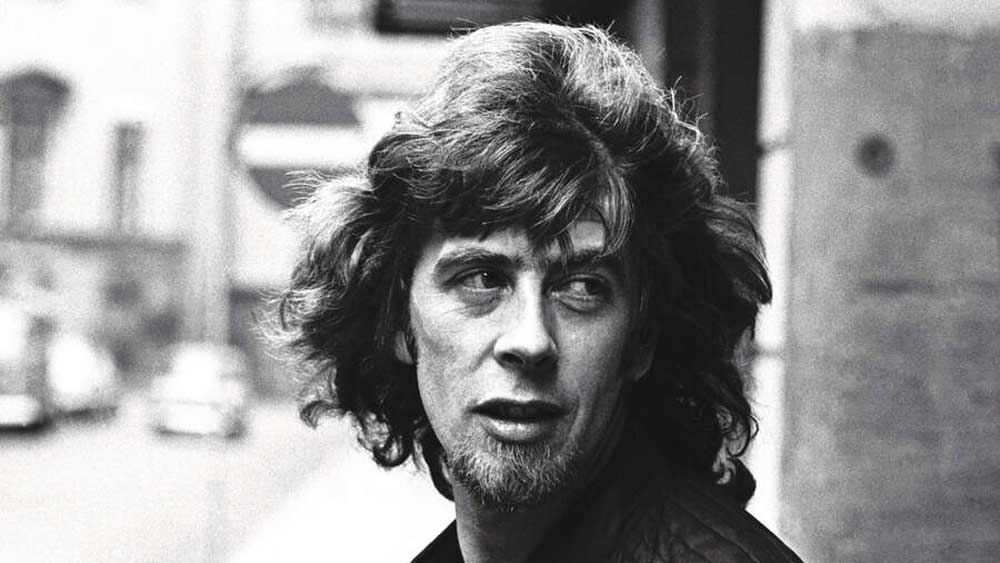

Mayall’s second studio album, A Hard Road, released in 1967, was another work of historic importance, introducing the fledgling genius of Peter Green - as not only lead guitarist, but also singer and songwriter - and laying the foundations of the band that would become Fleetwood Mac. Green, like Clapton before him, moved into a flat below Mayall’s at his new address in Bayswater for a while, and the two of them spent much time together listening to records and pooling ideas. Mayall encouraged him to write songs, suggesting that a good way to start was to borrow a line from one of his favourite blues songs and bend it into a new shape that was his own.

Mayall’s generosity in showcasing and nurturing the talents of the star players in his bands meant that his own abilities tended to be somewhat undervalued in the broader scheme of things. But he was a fine keyboard and harmonica player and a capable rhythm guitarist. And his high, sandpapery singing voice was an instrument of singular distinction. The ghostly, weather-beaten howl that he produced, for example on the title track of A Hard Road, drew on long years of emotional investment in the music, such that he was able to locate a unique and authentic blues voice of his own – no mean feat for a white guy from the north of England.

Mayall was incredibly prolific in every department. He released three albums in 1967 alone: A Hard Road - for which he also painted the imposing band portrait on the cover and wrote the sleeve-notes; the follow-up Crusade, which introduced the 18-year-old guitarist Mick Taylor to the group; and a solo album The Blues Alone, on which he not only wrote all the songs but also sang and played all the instruments himself apart from the drums.

Mayall was also a hard-nosed businessman. “I’ve kept away from managers,” he told me. “If you can get yourself together with the business end of gigs and your career, why part with a percentage of your earnings which you could make better use of? I’m the manager.”

His booking agent Rik Gunnell, who set up Mayall’s first tour of America at the start of 1968, was astonished to discover that his client had returned to London from the adventure with $2,000 (about $15,000 in today’s money) stuffed into his boots.

“At this point in the history of touring bands, I was unique in that I’d actually come home with a profit,” Mayall recalled in his book with Joel McIver, Blues From Laurel Canyon, published in 2019. “This was literally unheard of given our modest tour income and the high cost of living in America.”

The American trip was the beginning of a love affair with the country, particularly Los Angeles and the West Coast, and the start of a period of reinvention and experimentation. In May 1968 he abruptly disbanded the Bluesbreakers and returned to California, where he hung out with Frank Zappa and various members of Canned Heat. The adventure was documented on the 1968 record Blues From Laurel Canyon, a ‘concept’ album of sorts in which the tracks, all written by Mayall, segued together to form a single body of work.

In 1969 Mayall bought a house in Laurel Canyon and moved to California, where he would remain a resident for the rest of his life. Mick Taylor, who had been retained in the post-Bluesbreakers line-up, jumped ship in June 1969 to replace Brian Jones in the Rolling Stones, and the next iteration of Mayall’s band was a drummerless, primarily acoustic quartet that released two albums: The Turning Point (1969) and Empty Rooms (1970). He then hired an all-American group featuring guitarist Harvey Mandel and bass player Larry Taylor, both ex-Canned Heat, and – still without a drummer – banged out USA Union, his second album release of 1970.

The speed and diversity of his recorded output – with new albums from completely changed line-ups appearing seemingly in the blink of an eye – kept Mayall several steps ahead of his audience. Many fans from the 60s failed to keep up as he blazed a trail through the 70s working with mostly American musicians and moving into fresh musical areas on albums such as Jazz Blues Fusion (1972), and Notice To Appear (1976), a collaboration with the influential New Orleans songwriter Allen Toussaint.

Disaster struck in 1979 when a brush fire destroyed his home in Laurel Canyon, taking with it Mayall’s diaries, his father’s diaries, various master recordings, original artwork, books, magazine collections and much else besides.

In 1982, Mayall re-formed the Bluesbreakers with a temporary line-up featuring Mick Taylor and John McVie. The reaction was so positive that in 1984 he decided to relaunch the band/brand on a ‘permanent’ basis, recruiting the guitarists Coco Montoya and Walter Trout together with drummer Joe Yuele. There followed a long stretch of relative stability, and once Buddy Whittington took over on guitar in 1993 the core line-up remained largely unchanged until 2007 – an astonishing stretch compared to the glory days when Clapton, Green and Taylor passed through in less than five years.

Mayall turned 70 in 2003, and at the end of a typically busy year of touring, the Bluesbreakers marked the occasion with a special 70th Birthday Concert at the 4,500-capacity King’s Dock in Liverpool. The show, in aid of UNICEF, found Mayall reunited on stage with Clapton, 38 years after the Beano album. “For so many years I have dreamed of something like this event being possible,” Mayall wrote on the sleevenotes to the live DVD and double CD documenting the concert. To round off the year, the BBC screened an hour-long documentary on Mayall’s life and career, titled The Godfather Of British Blues.

Mayall was awarded an OBE in the 2005 Queen’s Birthday Honours list, for services to music, and he was inducted into the Rock And Roll Hall of Fame in October last year. He disbanded the Bluesbreakers for the last time in 2007, but soon set off again under his own name with a new core line-up which he emphatically described in 2011 as “the best band I’ve ever had”, with guitarist Rocky Athas (replaced in 2018 by Carolyn Wonderland), bass player Greg Rzab and drummer Jay Davenport.

Mayall continued touring and recording until he was 89. His last dates in the UK were a string of six shows crammed into three nights at Ronnie Scott’s in London in April 2019 as part of his 85th Anniversary Tour, and a final show later the same year at the Alban Arena, a venue where he had the distinction of being the first act to perform when it was opened (as St Albans City Hall) in 1968. His final show was at The Coach House in San Juan Capistrano, California on March 26, 2022.

For most of his life, Mayall was a man forever in a hurry. His albums were made on the hoof, with recording sessions shoehorned into days off here and there from his punishing gig schedule.

“It’s very easy to make a record,” he said. “For me it’s a very quick affair. You just go into the studio in the day and do it. That’s it. There’s no problem with it. You want to capture the feelings of the songs without belabouring them, and that’s the way it always has been for me.”

He could be impatient and occasionally cantankerous. When I was hired to write a biography of him for his record label in 2006, the first thing he told me was that he didn’t intend to waste any time talking about the old days. “Go and look it up,” was his terse response to my opening question.

But when I last spoke to him in November 2022, I found him in an unusually cheerful and contented mood. He said he couldn’t remember much about the 60s, and insisted that he was still touring and intended to carry on “as long as there’s an audience out there”. His long-standing secretary, Jane, gently informed me afterwards that, owing to general health and memory issues, he was not, in fact, touring any more. But I like to think that in his mind’s eye he was indeed still out there somewhere on the blues highway, readying himself for the next gig. “And it’s a hard road till I die…”

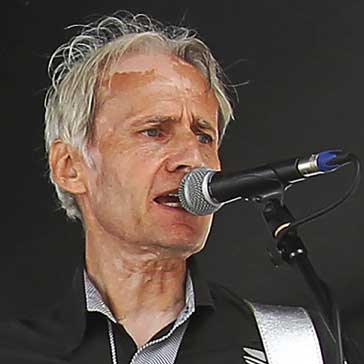

Musician since the 1970s and music writer since the 1980s. Pop and rock correspondent of The Times of London (1985-2015) and columnist in Rolling Stone and Billboard magazines. Contributor to Q magazine, Kerrang!, Mojo, The Guardian, The Independent, The Telegraph, et al. Formerly drummer in TV Smith’s Explorers, London Zoo, Laughing Sam’s Dice and others. Currently singer, songwriter and guitarist with the David Sinclair Four (DS4). His sixth album as bandleader, Apropos Blues, is released 2 September 2022 on Critical Discs/Proper.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.