"He was being very naughty under the piano with a woman at the same time he was singing": The epic story of the ‘stolen’ song that could be the next Stranger Things hit

Deep Purple's Child In Time has a long and complicated history – and now a whole new audience are hearing it for the first time

Kate Bush's Running Up That Hill and Metallica’s Master Of Puppets were both introduced to a new generation of fans after soundtracking pivotal scenes in the fourth season of sci-fi drama Stranger Things, and it's possible season five will do the same for Deep Purple.

The newly released trailer for what Netflix says is the final series of Stranger Things is dominated by a dramatic remix of Child In Time, a song so gargantuan that one wonders why it hasn't been used for this sort of thing before.

Released in June 1970 and featuring on Purple’s fourth album, In Rock, Child In Time was hard rock’s first truly epic song, beating Led Zeppelin’s equally heroic Stairway To Heaven to the punch by four months. There had been long songs before, including The Doors’ The End and Iron Butterfly‘s mammoth 17-minute In A Gadda Da Vida, but this was something else: a growing storm of organ, guitar and howling screams that erupted and died away, then erupted again before culminating in a thunderous climax.

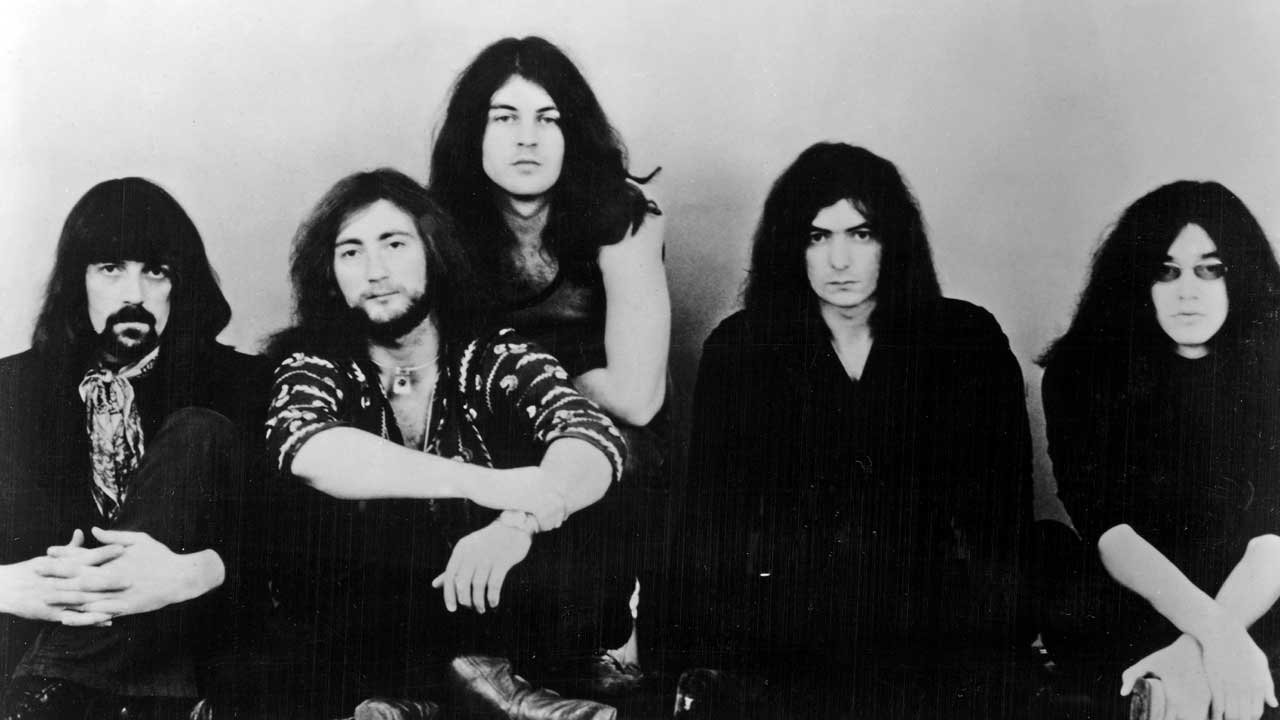

Deep Purple had already made three studio albums before In Rock with original singer Rod Evans and bassist Nick Simper, 1968’s Shades Of Deep Purple and The Book of Taliesyn, plus 1969’s Deep Purple. They’d even notched up a surprise US hit with their organ-driven cover of Joe South’s Hush. But guitarist Ritchie Blackmore, keyboard player Jon Lord and drummer Ian Paice felt that Purple were lacking direction, and that Evans and Simper were holding them back. Seeking replacements, they landed on vocalist Ian Gillan, then with pop band Episode Six, who suggested they also recruit Episode Six’s bassist and co-songwriter Roger Glover.

“It was a real eye opener,” Glover told Dutch TV show Top 2000 A Gogo of his new bandmates. “I’d never met musicians like that. They weren’t just good, they were brilliant.”

The new ‘Mk II’ line-up immediately began writing songs for the album that would become In Rock. Child In Time was the second thing they came up with, even if it was inspired by an existing instrumental number titled Bombay Calling by US psychedelic band It’s A Beautiful Day, who Purple had played with in America.

“It was in 1969, and the group was rehearsing at the Community Centre, which is in the western part of London: either in Southall, or in Hanwell,” Gillan wrote on his website. “Jon Lord fiddled (or ‘improvised with a theme’, as they say in the profession) with a tune from the new It’s a Beautiful Day album. It was Bombay Calling.”

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Gillan’s lyrics were inspired by Cold War tensions between America, the UK and Western Europe on one side and the USSR and the communist Eastern Bloc on the other: “Sweet child in time/You’ll see the line/The line that’s drawn between good and bad.’”

“We were in the middle of the Cold War at that time,” Gillan told Top 2000 A Go Go. “Things were terrifying. A lot of songs were written along that base, but you never tried to be too literal with a song, you never tried to say, ‘It’s gonna blow me up and kill me.’ You try and be poetic if you can.”

The song itself represented a musical battle too, between Ritchie Blackmore and Jon Lord. “It was all about the instrumental side of the band,” said Glover. “Ritchie and Jon [both] wanted a solo. Ian Gillan describes the band as an instrumental band with vocal accompaniment.”

Gillan himself found himself in the middle of this tug-of-war. “They never used to listen to me about the key,” he said. “‘The key is too high…’ ‘Well sing higher…’ So in the end I just kept going up and up and up.”

Purple began playing the song live almost immediately, debuting it at a gig in Amsterdam in August 1969. Gillan’s full-blooded performance saw him shift from restrained singing to banshee scream. “I always thought of Child In Time not as a song but more like an Olympic event,” he of singing the track live. “It was so challenging.”

For all his issues with what was being asked of him, Gillan effortlessly nailed the song when the band recorded it during the In Rock sessions.

“Ian did a remarkable job, a brilliant job of his falsettos, where he went up in steps,” Ritchie Blackmore later said. “And he did about two takes in the studio. Mind you, he was being very naughty under the piano with a woman at the same time he was singing, so maybe he was inspired by that, I don’t know.”

According to Blackmore, the singer wasn’t completely happy with his performance. “He came in and heard it, and said, ‘I want to change it, I want to do better,’’ the guitarist said. “We said, ‘No, you’re done a brilliant job, let‘s put it out like that.’ And Jon and I made sure he didn’t change it. It was just wonderful how he did that.”

Another person who was impressed by his delivery was Tim Rice, lyricist partner of composer Andrew Lloyd Webber. Rice had been given an early acetate of Child In Time by Purple co-manager Tony Edwards and enlisted Gillan to perform as Jesus on the original album version of the pair’s new musical, Jesus Christ Superstar (Gillan turned down the offer to appear in the subsequent stage play, preferring to focus on Purple).

In Rock was released on June 5, 1970, It opened with the blazing Speed King, but it was Child In Time that was the true showstopper – 10 minutes of towering build and release. Any potential issues with It’s A Beautiful Day, the band whose song Purple had ‘borrowed’ for Child In Time, were headed off at the pass.

“When we saw It’s A Beautiful Day in London, we said, ‘I hope you don’t mind but we stole your idea,’” said Blackmore. “They said, ‘Yes we know.’ But they’d stolen one of our ideas, [a Purple song titled] Wring That Neck. So we shook hands and said, ‘We won’t sue you if you don’t sue us.’”

Child In Time was well established as a live favourite by this point, but it became lightning rod for the tensions between Gillan and Blackmore that would only intensify over subsequent months.

“It was just that much too high,” said Gillan. “If you had a cold or a strain, I’d say, ‘No Child In Time tonight guys, either I can’t sing it or it’s gonna put me out of work for two weeks.’ And then Ritchie would start playing it. And the next night he would do it again. And the next might. He got great pleasure from it.”

The animosity between the two men eventually contributed to Gillan handing in his notice following 1973’s Who Do We Think We Are album. He was soon followed out the door by Roger Glover, with the pair being replaced by David Coverdale and Glenn Hughes respectively. Child In Time was dropped from Purple shows, though Gillan himself recorded a jazzier version of the track with his post-Purple outfit the Ian Gillan Band (the latter’s 1976 debut album was even titled Child In Time).

After the Mk II line-up reunited in 1984, the song was reinstated into the live show, though it was played less and less frequently as the years went on. In 2002, Child In Time was retired for good from Deep Purple’s live shows, with Gillan acknowledging that he couldn’t deliver it with the power he once had.

“When I was young, it was effortless,” he said. “So we got to the point when I got to about 38 years old, and it just didn't sound right. So I thought, 'Better not to do it badly. Better not to do it.’ So it's been the same, and I never looked [back].”

But the elemental power of Child In Time remains undiluted. Metallica drummer and Purple uber-fan Lars Ulrich told Rolling Stone that it remains “their most iconic moment… I've heard it 92,000 times, and it never sounds anything less than great.” For Roger Glover, it showcased Purple at their most unfettered. “It’s powerful and crazy and loose,” the bassist said. “There’s a sense of freedom when you listen to it.”

Dave Everley has been writing about and occasionally humming along to music since the early 90s. During that time, he has been Deputy Editor on Kerrang! and Classic Rock, Associate Editor on Q magazine and staff writer/tea boy on Raw, not necessarily in that order. He has written for Metal Hammer, Louder, Prog, the Observer, Select, Mojo, the Evening Standard and the totally legendary Ultrakill. He is still waiting for Billy Gibbons to send him a bottle of hot sauce he was promised several years ago.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.