Glenn Hughes has played with Deep Purple, Black Sabbath, Black Country Communion and more - but he should never have left his first band

Glenn Hughes has spent more than 50 years in rock - and he's ready to talk about it all

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

Thirty seconds into our conversation, Glenn Hughes starts fiddling with his earbuds. “Give me a second,” he says, with a California smile, a healthy tan offsetting his immaculate white teeth. “I’m still deaf from working with Jon Lord.”

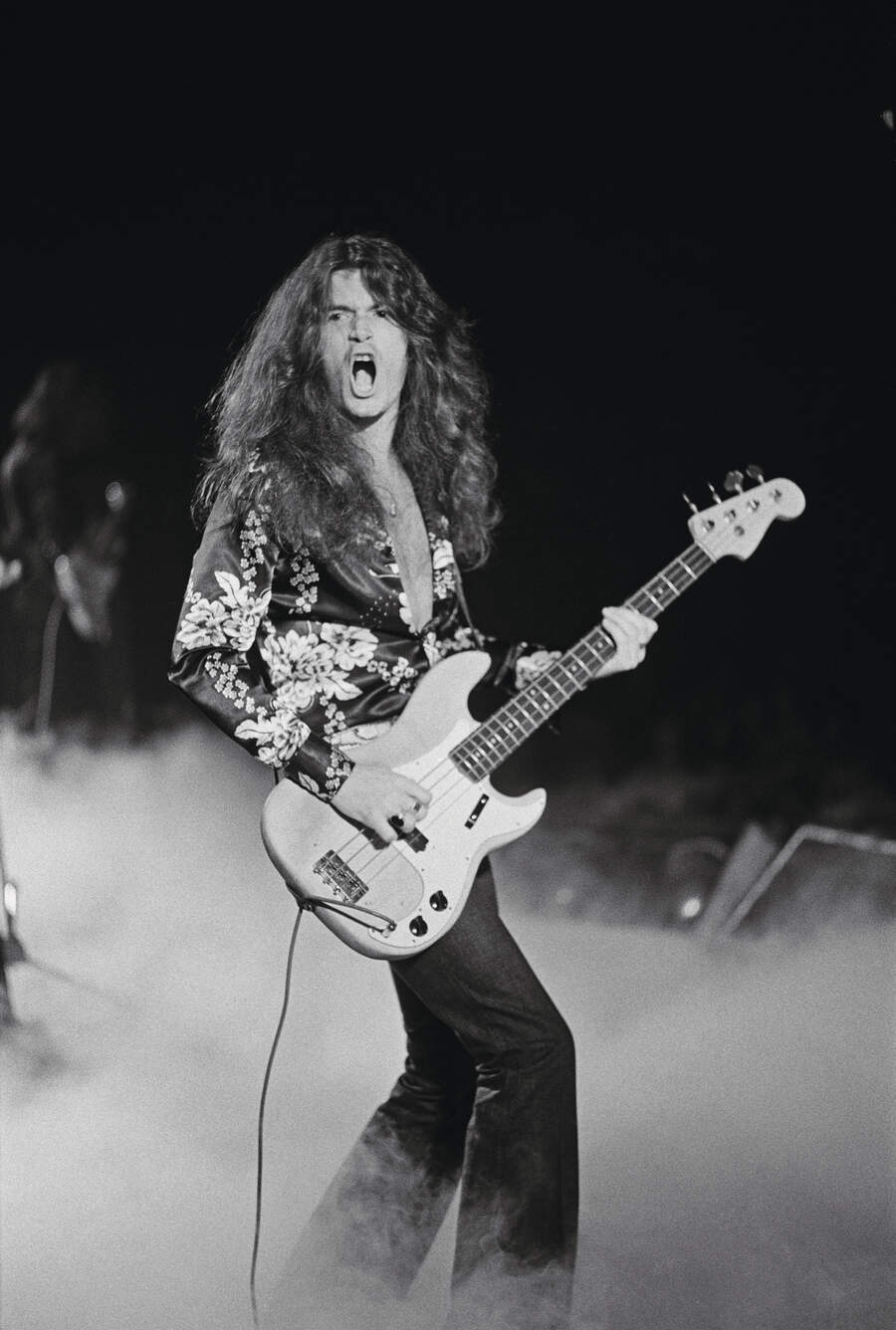

If battered eardrums is the only residual damage that Cannock, Staffordshire-born Hughes has to show from more than 55 years in rock’n’roll, he’s got off lightly. The bassist and singer was one of hard rock’s thrusting young bucks through the 70s, making a trio of great, if underrated albums with his original band, Trapeze, then another three as part of Deep Purple’s Mk III and IV line-ups.

The latter trilogy – 1974’s Burn and Stormbringer and 1975’s Come Taste The Band – rejuvenated Purple after the departure of vocalist Ian Gillan and bassist Roger Glover. Inspired by soul and R&B, Hughes brought a funk edge to a band not previously renowned for their funkiness, not to mention powerhouse vocals that dovetailed perfectly with fellow newbie, singer David Coverdale.

Not everyone was happy – not least Purple guitarist Ritchie Blackmore, who quit in disgust at the direction the band were taking (hotshot American guitarist Tommy Bolin replaced him for Come Taste The Band).

After Purple fell apart in 1976, Hughes embarked on a solo career. His debut album, 1977’s Play Me Out, was his answer to David Bowie’s Young Americans – a white English rock guy channelling the black American music he loved. But any promise he had was holed below the waterline by a heavy-duty drug addiction. From the late 70s to the early 90s, Hughes wasn’t so much a musician with a drug problem as a drug addict with a music problem.

“I didn’t plan on becoming a drug addict when I was five years old,” he says now. He’s been studying Buddhism for the past 15 years, and says everything he went through back then was pre-ordained: “I believed it was meant to happen in my storyline, in this particular lifetime.”

Fate or not, he finally cleaned up once and for all in 1997. Since then he’s released a string of great solo albums, some of them rocky, some of them funky, some of them both. He’s also been a member of a handful of bands, including the short-lived California Breed (alongside future Ozzy/Rolling Stones producer Andrew Watt), and, more notably, Black Country Communion, the blues-rock supergroup he formed with guitarist Joe Bonamassa, drummer Jason Bonham and keyboard player Derek Sherinian.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

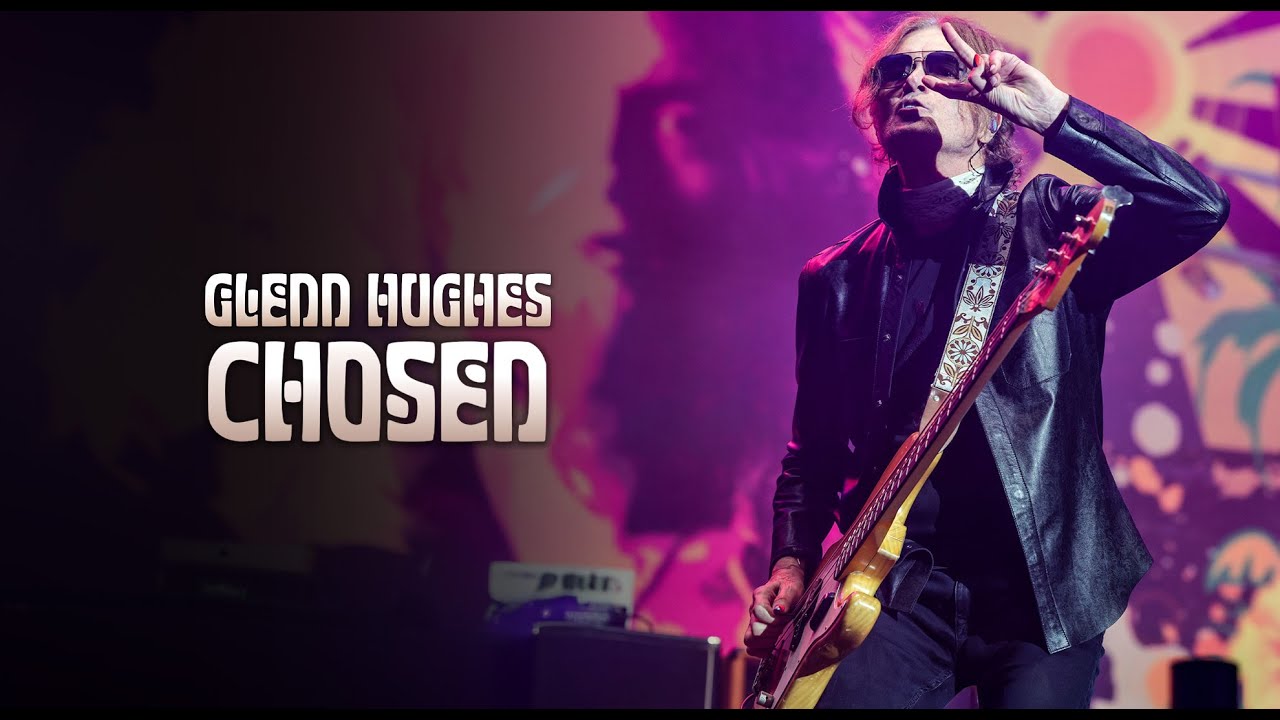

He’s here to talk about his new solo album, Chosen. It’s his first since 2015’s Resonate. And that’s not all.

“This may be the last Glenn Hughes solo album,” he says. “It was suggested that I needed to do one for the label, I owed them an album. So I thought: ‘Okay, if that’s the way it’s going to be’, and I wrapped my head around it. Solo albums, for me, are very personal. I like to make records when I have something to say. I don’t think about genres any more, I just think: ‘How is this going to sit with me?’”

Chosen sounds like anything but a contractual obligation. It’s as powerful and soulful as Resonate or 2005’s acclaimed Soul Mover, the latter his late-career tipping point. But if it does prove to be his solo swan song, it will cap a career that’s taken him to the highest highs and the lowest lows.

Your first instrument was the trombone. This could have been a very different conversation.

When I was twelve years old, the principal of my school was looking to put an orchestra together and somehow they chose me to play the trombone. So I started to learn how to play trombone and read music. It wasn’t what I wanted to do, but playing the trombone led to playing the piano and then to playing the guitar.

Why did you end up gravitating to bass?

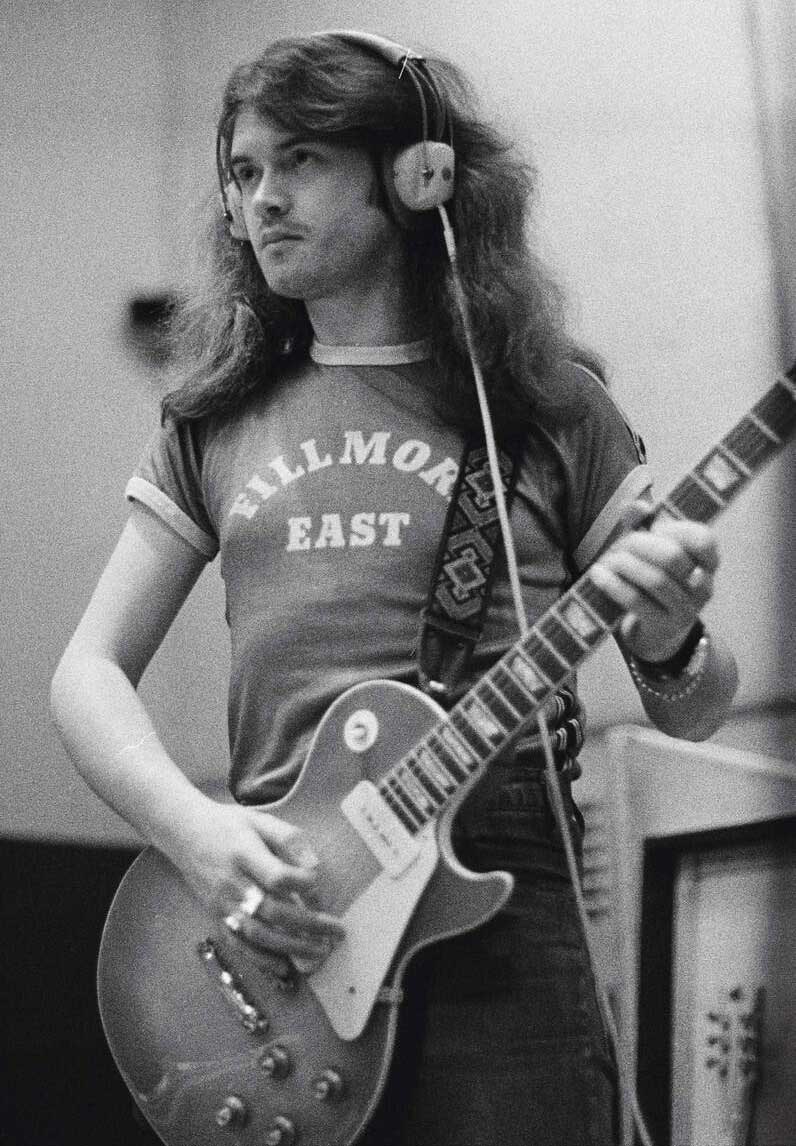

Well, at thirteen I was a guitarist. There was a kid three of four years older than me named Mel Galley, who also played guitar. I used to see him playing gigs in Cannock and he became my idol. I loved watching him play. I used to mimic everything he did, I tried to look like him. And he knew I was this budding little guitar player.

Mel joined a band called Finders Keepers, and about a year later their bass player left. And he said: “I know a young kid from my home town, maybe he could switch from guitar to bass.” Within twenty-four hours I was learning how to play bass, simply so I could play in a band with Mel.

You were already a huge fan of black American music at that point. What was it about it that resonated with you?

I didn’t choose it, it was meant to happen. When I was fifteen my girlfriend’s brother ran a discotheque in Walsall on the weekends. I’d go with them and fetch him coffees and Cokes. I ended up hearing all this great music - Tamla Motown, Stevie Wonder, Al Green, Marvin Gaye. All of this music was slowly but surely etched into who I was. Most of my schoolfriends were listening to The Beatles and the Stones and Dylan, but for me it was R&B. It was about the groove - the groove of James Brown. And the melodic vocals of someone like Stevie Wonder. Groove and melody is who I am.

You joined Trapeze when you were eighteen. What was it like in those early days?

It was incredible. The other guys were all older than me. Mel Galley was the next youngest, and even he was three years older. When I joined, there were five people in the band. I was the bass player that occasionally sang a few lines. But Mel and Dave [Holland, drummer] had a meeting with management behind my back, saying: “Glenn’s singing great. What if we could build a thing around him.”

They called me into the office and said: “How would you feel about fronting the band?” I went: “What?!” I had no idea this was happening, by the way. I was just finding my voice back then. And I felt bad that we had to let [original vocalist] Johnny Jones go. I still love that five-piece line-up. Trapeze is still the most important music I ever made.

Really? Why?

Because of my dear love for Mel and Dave, and working with those two people so closely in Cannock all those years ago. We were so in tune with each other as a trio, musically. Mel was getting into groove music along with me, Dave Holland was a really great drummer. Oh my god, that band was everything to me.

You were asked to join ELO at one point. What would that have sounded like?

This was around 1971. I was hanging out with [ELO co-founder] Roy Wood when his previous band The Move were breaking up. Roy was one of my close friends, and he obviously thought it might be something that could work. [ELO’s notorious manager] Don Arden came to see me: “Hey, you want to take a meeting with me?” He sat me in the back of his Rolls-Royce, smoking a cigar, and asked if I wanted to join ELO. I was too frightened to say no, so I said: [meekly] “Of course”. I really didn’t want to do it. My mum called Roy Wood up a week later and said: “Roy, he’s having a meltdown, he doesn’t want to join”. My mum had to tell Roy Wood I couldn’t join ELO.

What would ELO with Glenn Hughes have sounded like?

You had Roy and Jeff [Lynne], two insanely great writers and leaders of the band, and they wanted me to be a singer and a bassist.

What would that have been like?

I’m an R&B guy. I’m not sure it would have worked.

Instead you stayed with Trapeze. Should that band be better known than they are?

We were one song away from cracking it. Medusa [1970] was heavy, but here we come with [1972’s] You Are The Music… We’re Just The Band. Coast To Coast, Way Back To The Bone, What Is A Woman’s Role, You Are The Music… all these fantastic, groovy, crossover R&B songs. Oh my god, we were so close. I should never have left.

But you did. You replaced Ian Gillan in Deep Purple in 1973.

They’d been watching me for a year – they’d seen me with Trapeze at the Marquee in London, at the Whiskey A Go Go in Los Angeles, all these places. I was in Baltimore, Maryland with Trapeze the same week Purple were in New York where they were playing a show. Jon Lord flew me in, so I had a feeling something was going to happen.

I watched the show from the side of the stage, and the next day I was in a meeting with Jon, Ian Paice, Ritchie and their managers and attorney. And they said: “Would you like…”, and I thought they were going to ask me to be the lead singer. But they said: “We would like you to play bass guitar, because we’re going to ask Paul Rodgers to sing”. I thought: “Really? You just want me to play bass?” So I basically said no. I was very respectful: “It’s not what I really want to do”.

Why not?

Trapeze were established, and I was a lead singer. I didn’t want to do something that I didn’t think was appropriate. Deep Purple’s music was very classic, very square, white-boy rock. I wasn’t that way. I thought: “Is this really what I want?” I wasn’t interested in doing it to make money and I just didn’t know if I’d be happy in that scenario. I wasn’t just going to come in and sing ‘ooh’s and ‘aah’s.

Why did you change your mind?

It was the idea of singing with Paul Rodgers. I thought: “I have this voice, there’s a possibility we can explore this”. I think it would have been great, the two of us, but obviously it didn’t happen. And after I joined, David [Coverdale] came in. And by the way, David and I worked brilliantly together. While we were writing the Burn album in Clearwell Castle we had two microphones set up. David and I would look at each other and go: [politely] “After you…”, “No, after you, I insist…” There was a lot of respect there. But they knew I had that voice.

What was Ritchie Blackmore really like?

When I joined the band in June 1973, Ritchie took me to Hamburg. We sat on a barstool in a bar for three or four days, and we had the most amazing time. He told me so much about himself, he had so much aspiration for what I was bringing into the band, he was giving me so much encouragement. One-on-one with Blackmore, it was fantastic. [Laughs] We only had one one-on-one moment, and that was it.

That aside, what was the most Ritchie Blackmore thing you saw Ritchie Blackmore do?

When we were going down really well at shows, he would refuse to do an encore. He would have to be forced to go back on stage, and even then he’d play behind his equipment. It was so ridiculous. You couldn’t make him do anything.

What did you learn from him?

What I did learn was the stuff that I didn’t agree with. He was an isolator. He had his own dressing room, his own car. It wasn’t a band, it was us and it was Ritchie. That’s been his thing for ever. It was uncomfortable for me. I missed the family aspect of all of us together. It was a strange situation.

Can you settle something for Deep Purple fans: which Purple album is the best: Burn, Stormbringer or Come Taste The Band?

Stormbringer.

Really?

Yes. We knew Ritchie was leaving the band. He’d brought in Stormbringer and Soldier Of Fortune and couple of others, but Jon, David and myself were left to write the album. Nobody said: “You can’t be funky”. And if you leave me in a room with Jon Lord and David Coverdale, that’s what you’re going to get. I was writing songs like You Can’t Do It Right (With The One You Love) and Hold On and Love Don’t Mean A Thing… A lot of Purple fans didn’t like the album cos it was too damn funky. But if you give me the opportunity, that’s what happens.

Have you still got those fantastic furry boots you had back then?

I don’t. I’ve moved house so many times since then. And my dad gave a lot of stuff away. Fans would come knocking on his door in Cannock and he’d give them my stuff.

Drugs entered the picture for you during your time in Purple. How did you step onto that path?

When anyone has success, there will be people around offering them stuff - jewellery, watches girls, drugs. When I joined Purple I was given all kinds of drugs, pills, things like that. I’d flush them down the toilet or just leave them in my pocket and not do anything with them.

After about six months in Purple, I started to go: “What is this stuff about, cocaine?” One night, I found something in my pocket. I was alone in my room, and I sniffed some of it. I went: “Oh, this is fun. This is making me happy”. Slowly but surely I started becoming addicted. I thought: “I’m young, isn’t everybody snorting cocaine off of strippers’ bums?”

Part of it for me was that maybe I wasn’t that happy. It was glamorous in Deep Purple, everything I ever wanted was there, yes, but I just wasn’t as happy as I should have been. With respect to David, I was a lead singer when I joined the band, and now I was basically known as the second singer. I loved singing with David, we sang brilliantly together, we had a great friendship and camaraderie, but all along I was thinking: “I shouldn’t have joined the band, because I really need to be singing”.

Deep Purple ended in 1976. Were you relieved?

I was relieved in a way. I was desperately in trouble, really not great. It gave me the opportunity to slow down and address how I was going to continue to live my life.

You and David Bowie had come into each other’s orbit by then. What was that period like?

David was living at my house in LA in March 1975 - he was in his Thin White Duke era. We were jamming, writing stuff, just the two of us. Even then, he said: “You should be thinking about what your next move is”. We talked about doing an album together.

David was in his whole soul/ R&B thing back then, which was my world completely. He’d recorded Young Americans, which was fantastic, so I decided I was going to make an album in that R&B mould. I started writing [Hughes’s 1977 debut solo album] Play Me Out with him in mind to do it with me. Unfortunately he wasn’t available to produce it.

Did you ever record anything with him?

No, I didn’t. He invited me to sing on Young Americans, but Blackmore advised me not to do it. He was quite angry that I even suggested it. So that didn’t happen.

What was the best lesson you learned from Bowie?

I’d watched every incarnation of his through the seventies. He always used to tell me: “You’ve got to keep changing, Glenn”. When he moved in, some of my clothes started disappearing – the bell-bottoms and boots vanished. He talked about cutting my hair. He was upset that I was still fascinated by Stevie Wonder. He turned me on to Nina Simone He kept telling me that you have to keep changing. I’ll never forget that.

Hughes never got a chance to put Bowie’s advice into action. The drug addiction that had taken hold during his time in Deep Purple had grabbed him in a death-lock embrace. Cocaine was his poison of choice, and by the early 80s he’d graduated to freebasing and smoking crack.

For anyone who wants to read those stories, his brutally honest 2011 autobiography lays them bare: holing up in his apartment like a vampire; ruining relationships; almost setting himself on fire with a chip pan after a five-day cocaine binge; the friends he almost lost to drugs and the ones he did lose; the heart attack he had just before he checked into the Betty Ford clinic… The 1980s Glenn Hughes, bearded and bloated, was a walking warning that the rock’n’roll junkie-pirate myth was anything but glamorous.

His dire physical and mental state was reflected by the paucity of his discography during that period: an 18-month collaboration with Canadian guitarist Pat Thrall under the name Hughes Thrall that produced one self-titled album (an overlooked gem of early-80s rock), a brief musical hook-up with Gary Moore on Moore’s 1985 album Run For Cover (the pair fell out halfway through over Hughes’s drug use) and an ill-fated stint singing in Black Sabbath (in fairness, 1986’s Hughes-fronted Seventh Star was supposed to be a Tony Iommi solo album).

He started to pull himself out of this death spiral in the early 90s, but it would take a few more years before he completely kicked drugs and alcohol.

“People ask me how I survived,” he says. “I honestly don’t know.”

Do you regret not making more music in the 80s?

I couldn’t have. I wasn’t capable of it. I wasn’t engaged with making music. Music was getting in the way of me getting high. Getting high was the main thing for me. I tried to stop but I couldn’t. I was in trouble.

The Hughes Thrall album you made with Pat Thrall is a great record, through.

I saw Pat Thrall playing with Pat Travers in 1981 and I thought: “Oh my god, this is the funkiest white guy I’ve ever heard”. So I approached him in the toilet and said: “Why don’t you think about coming to LA and staying with me and maybe we can write something”. We connected and formed Hughes Thrall. That was an eighteen-month period of my life.

But other than that… Gary Moore and I put something together in 1980, but I wasn’t up to doing it. I fell out with Gary halfway through the album we did make [Run For Cover] because of it. Then the album I made with Tony… These albums are okay, but they weren’t great. My getting high was stopping me from leading a life.” You were doing cocaine and crack, but never got hooked on heroin.

How did you manage to avoid that?

There was one incident that happened. It was Tommy’s [Bolin, MK IV Deep Purple guitarist] birthday, August 1, 1975. We were in Munich, in this nightclub. There was some white powder, and me and Tommy sniff it up, thinking it was cocaine, and it was heroin. Tommy got a nice buzz – I didn’t realise that he may have been on the heroin path already. I got violently ill. They took me to a hotel and put me in a sauna. I was very sick. It was horrifying. Thank god heroin was not right for me.

The electronic duo The KLF invited you to sing on their 1991 single America: What Time Is Love. You were credited as ‘The Voice Of Rock’. How important was that in terms of getting your career back on track?

Really important. We got a call from someone in the KLF’s camp - they were looking for me or Roger Daltrey to sing What Time Is Love. I went down to the studio to meet the two KLF guys, and within an hour I’d sung what you hear on the song. They loved it and they asked me to be in the video.

I owe them a lot. I don’t think they knew anything about my drug addiction in the studio. I never showed up high. But I figured: “Holy shit, this could be my pathway to a different career - something strange but wonderful. Maybe this is the opportunity for me to take a look at my addiction”. I very obviously knew that I had a problem. Everybody I knew was praying for me. People were so pissed off with me, but they were praying for me. I decided when I got home to see if I needed to go into the Betty Ford Centre.

Even so, it took you several more years to clean up.

I got sober on Christmas Day in 1991, but then I had four or five relapses. Every seven or eight months I’d go to Amsterdam and get high. Then in November of 1997 I got home and I found myself doing some ecstasy. I freaked out, I thought I was going to have a heart attack. I called an ambulance, I said: “Come and get me”. I thought I was going to die, and I did not want to die loaded.

You credit the ambulance driver who picked you up that day for saving your life by giving you some very stark home truths.

I’m in the ambulance and I say: “I’m not like all the others who sit back here”. And the driver comes back and says: “Shut the fuck up, you loser piece-of-shit drug-addict cocksucker or I’m gonna come back there and beat the shit outta you”. And thank God he said that. That’s when I realised I needed to make a change. I was desperate to get sober. I was desperate for a lifestyle change. I was desperate to come back to the UK and see my mum and dad clean and sober. I’ve been sober ever since.

What did making records when you were sober feel like?

Did you feel reinvigorated? Musically, I think I was there. Personally? I had some stuff going on. But meeting my wife, Gabi, in 2001 was pivotal for me. Having a strong relationship at home, having that great family environment, it enabled me to become a better person. She’s the most amazing person in the world. We’ve been together in many, many lifetimes. Gabi and I are so connected.

Which is the album where it truly felt like Glenn Hughes was back?

Soul Mover [2005]. I stopped listening to record companies, I stopped listening to people saying: “We need an AOR record from you, we need this kind of record from you”. I said: “No, I’m going to make an album I want to make”. Soul Mover was an album of complete Glenn-isms. For me, that was an archetypal Glenn album.

That record features drummer Chad Smith and guitarist John Frusciante from the Red Hot Chilli Peppers and Dave Navarro from Jane’s Addiction. Was it a surprise that a younger generation of musicians wanted to work with you?

It was great. There aren’t many people of my generation who can actually reach out and work with those types of people. More importantly, these people are my friends. I feel blessed.

Then there’s Black Country Communion. That seemed to kick things to another level for you.

Joe Bonamassa and I are very, very close. We were having a conversation last night about the difference he sees in me over the last fourteen years. I guess I’ve changed so much.

You and Joe are both headstrong people. Are there a lot of egos involved in Black Country Communion?

Call it ego if you want, but there’s so much love here now. We are playing better than ever before, we are selling a bunch of tickets. The world of BCC is so great right now. This is first string of shows we’ve done since 2011, and it looks like there’s going to be more. There’s so much love and life.

But it hasn’t always been like that. After the second Black Country Communion album there seemed to be tension between the two of you. It looked like the band was over.

In 2011, when we did that nine-week tour of Europe, we were all in different places; Joe had really careened off into his solo thing. But it’s meant to be what it’s meant to be. We’re all on the same page now. The friendship and communion and camaraderie is off the scale.

Was it an honour to inducted into the Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame with Deep Purple in 2016?

It was very much an honour to be inducted. David and I were sitting at that table with those other fellows [laughs].

There were issues with “those other fellows”. What was that all about?

There were. David called me six months prior, when we knew we were going to be inducted, and said: “I’m going to call Gillan about you and I doing something. Maybe you and I could get up and sing”. I said: “Good luck, mate”, knowing full well that was not going to happen.

I don’t know Gillan and Glover very well, but when we sat at that table there was no camaraderie, no eye contact, no nothing. It was very uncomfortable. But I said to myself: “Stay there, be kind, be respectful, do your thing, enjoy it”. I really do respect Mark II, and Roger Glover seems to be okay, but those guys don’t want to acknowledge David and I. They were just rude. It was just wrong. All David and I wanted to do was just be there and represent.

You’ve worked with some incredible guitarists over the years. Who is the best?

Oh god, that’s really difficult. I don’t want people to be upset with me because I don’t mention Ritchie or Tommy or Mel or Pat, but I have to say it’s a tie between Gary Moore and Joe Bonamassa. I’m talking about the fever it has given me working with them. Gary coming to my house at three in the morning and just blowing my mind - it’s incredible what a guitar player he was. And Joe Bonamassa is blowing my mind every night. Bonamassa is the greatest right now.

Given everything you’ve put your body through, how the hell have you managed to keep your voice?

I read people saying: “How does he still do it every night?” And I go: “I don’t know!” I don’t know how I do it, I just know I do it. There’s a spiritual dimension to it, but I just don’t think about the next note, I just allow myself to do it and be present.

So many people you’ve known and worked with have passed away. If you can have one last conversation with someone we’ve lost, who would it be?

I’d love to speak to my mum again. I was there when she passed, and I saw things in that room with my own eyes that confirmed to me that there is an afterlife. She’s with me all the time. My dad passed away on the day of the Hall Of Fame. I was an only child from a working-class family in Staffordshire, and they got me my first guitar. They stood by me through everything. I miss them very much.

Have you had the career you wanted? Do you wish you’d made more albums or been more successful?

The word ‘success’ troubles me. What is successful? I probably would have liked to have been a solo artist, but I got strung out. But every single thing has happened to me for a reason. I believe we live predestined lives. I believe my life was laid out for me before I was born. Every single thing was meant to happen. I’m still here.

No regrets at all?

I don’t regret anything. But I should never have left Trapeze. I should never have left that band.

But you’d have missed out on so much, good and bad, if you hadn’t.

I didn’t enjoy being in Deep Purple. It wasn’t great for me. Musically it was okay. Why do I still play those songs? Because people want to hear them. But my solo career is what makes me happy. This is the real Glenn.

Is Chosen really going to be your last solo album?

If I’ve got something else to say, then I’ll let you know, but I don’t know if I will have. I’m not going to retire, but making a solo album tears me up. They’re so personal, they just do a number on me. I can’t make plans. If I make plans, God goes: “No way, pal, we’re not going to do that”. If Chosen is the last album I make, it’s an epic way to finish. But then again you never know with me.

Chosen is out now.

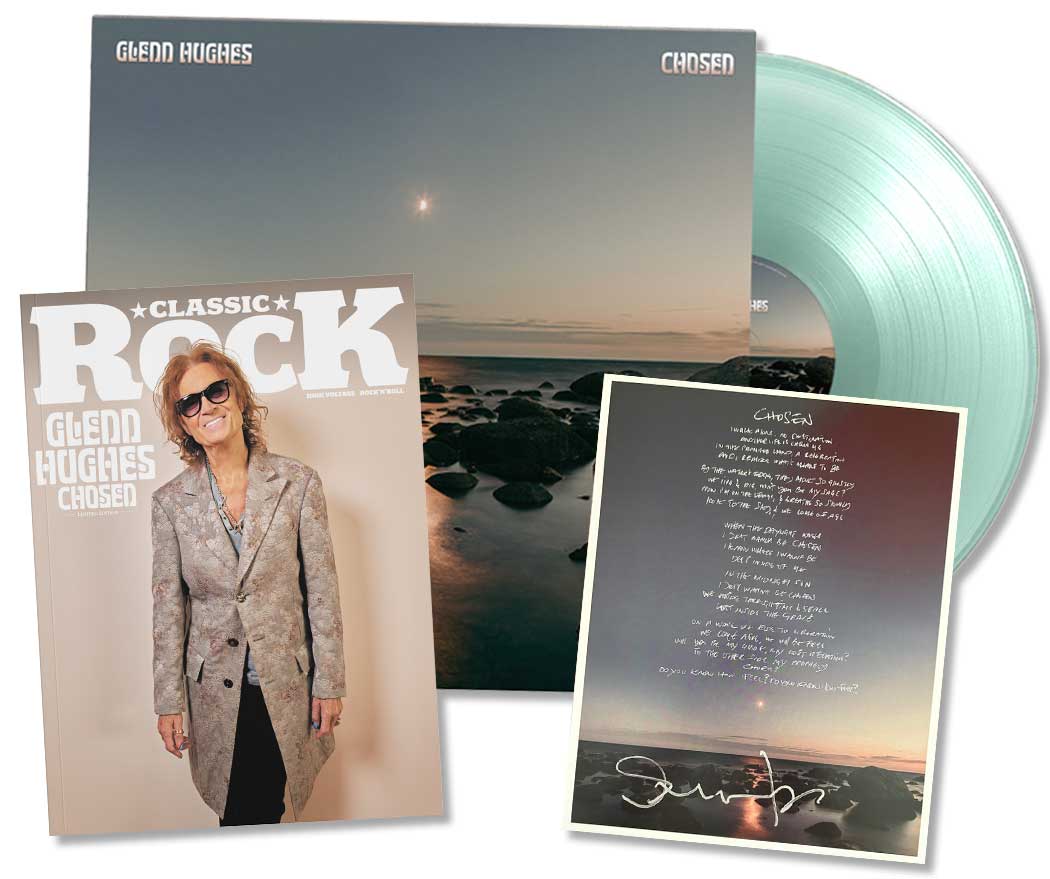

Glenn Hughes X Classic Rock Bundle Edition

Glenn Hughes’ latest solo album, Chosen, is out now via Frontier Records, and to celebrate we have a special edition of issue 344 of Classic Rock that features a limited-edition Glenn Hughes cover, a hand-signed lyric sheet, and an exclusive copy of the album on coke bottle clear vinyl.

Dave Everley has been writing about and occasionally humming along to music since the early 90s. During that time, he has been Deputy Editor on Kerrang! and Classic Rock, Associate Editor on Q magazine and staff writer/tea boy on Raw, not necessarily in that order. He has written for Metal Hammer, Louder, Prog, the Observer, Select, Mojo, the Evening Standard and the totally legendary Ultrakill. He is still waiting for Billy Gibbons to send him a bottle of hot sauce he was promised several years ago.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.