The mid-80s were tough times for bands with noisy guitars. Punk was long dead, while its American cousin, hardcore, was running out of gas, leaving poker-faced goths, fey indie types and cartoonish hair metallers to run riot.

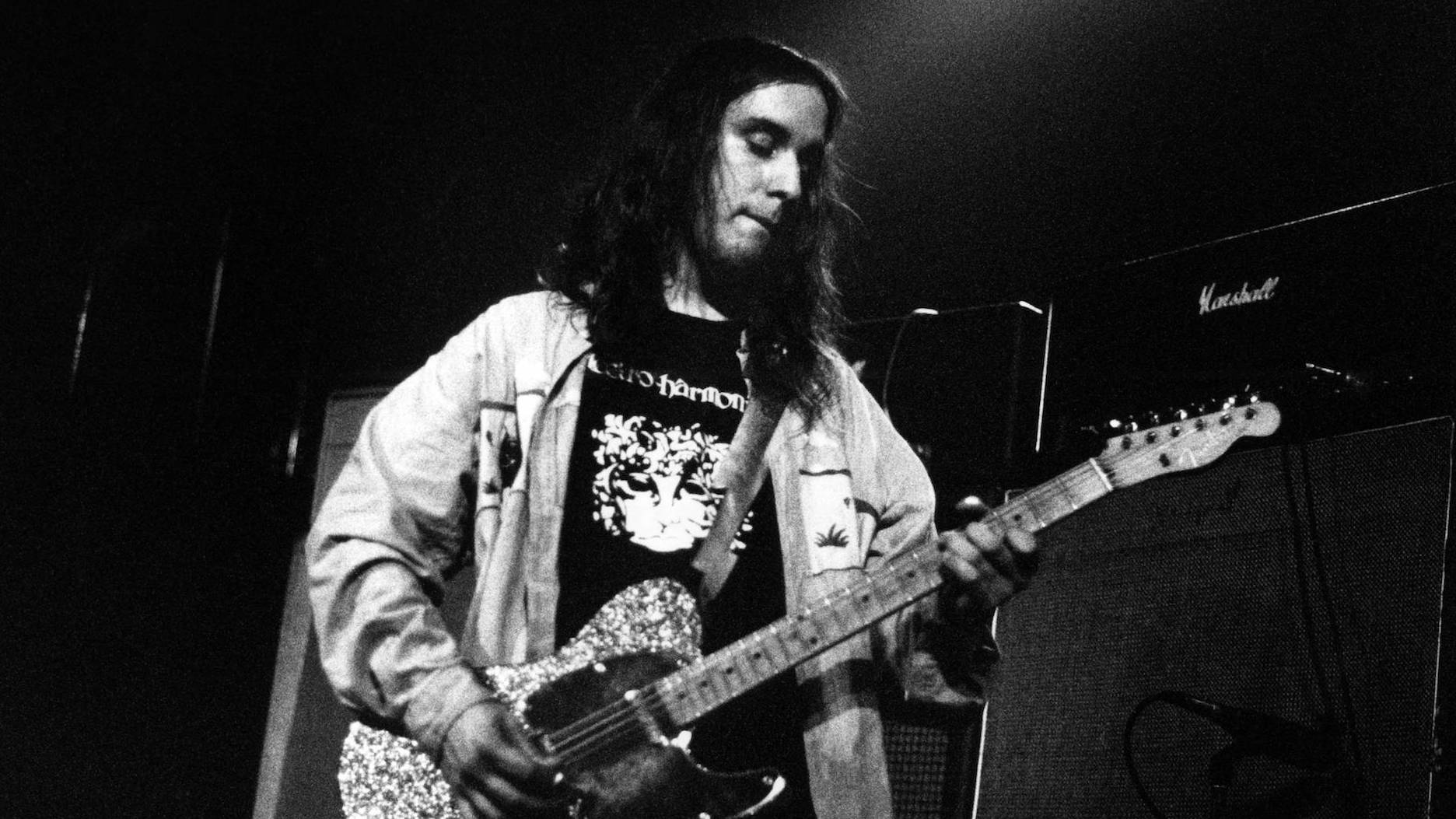

Into this void strode Dinosaur Jr., three suburban kids from Amherst, Massachusetts who invested the sounds of their heroes – Black Sabbath, Neil Young, the Stones, The Byrds – with the energy of Black Flag and Minor Threat, in the process reviving that most maligned of rock traditions: the guitar solo.

Released in September 1988 as the lead single from Bug, their third album, Freak Scene was where everything peaked. It was the definitive alt.rock anthem, a three-and-a-half-minute barrage of sound that opened the door for grunge while also finding room for not one but two face-melting guitar solos. But it also represented the nadir of the band’s internal tumult, signalling the end of this incarnation of Dinosaur Jr. just as they made their breakthrough.

Parent album Bug was recorded at Fort Apache North, the Boston studio run by engineers Paul Q Kolderie and Sean Slade, who would go on to work with the Pixies, Hole and many more. “Fort Apache was better than anywhere else we’d recorded,” Mascis remembers today. “It sounded better than the stuff we’d done before.”

But neither he nor Barlow remember the sessions fondly. “J was just so passionless in his whole approach to it,” Barlow recalls.

“Bug was a bad time,” Mascis adds. “The band was falling apart. It reminds me of when I got to interview Ozzy Osbourne and was asking him about Sabotage. He hated that record because it reminded him of being in the studio with all these lawyers and having a really bad time. So much so that he couldn’t listen to it any more. Bug was kind of a similar thing.”

- How Paranoid Made Black Sabbath Heavy Metal Superstars

- Nirvana: From Zeroes To Heroes

- My Bloody Valentine: 14 Very Metal Love Songs

- The story behind Pixies' Debaser

Compared to the more sprawling songs that made up the rest of the album, Freak Scene was more straightforward. Musically, its collision of melody and raw noise was partly indebted to Mascis’ beloved Black Sabbath. But Barlow was initially unsure about the song’s merits. “Don’t get me wrong, I love it,” he says. “But my first impression was: ‘Wow, J’s aiming real low with this one.’ I usually wasn’t critical of his songwriting, as I kind of worshipped his ability, but it was very simple compared to these instrumental epics that he was coming up with.” “It was poppier,” concedes Mascis. “It was probably about trying to deal with people or friends trying to communicate with me. It was kind of pointing out some weird relationship.” The album marked the apex of Mascis’ authoritarian approach in the studio. He insisted on scripting all the instrumental parts for each song, then telling Barlow and Murph (drums) how to play them. “Freak Scene was one of the first ones we did like that,” Barlow confirms. “He had the whole thing down: ‘These are the chords you’re gonna strum on bass.’ Whereas before, I was always given more wiggle room in terms of coming up with my own parts.”

Mascis admits that it all added to the fractious atmosphere: “I thought it was the easiest way to spend the least amount of time together.”

The song’s lyrics were entirely apposite. The tale of a love-hate relationship caught in irresolvable flux, it could’ve been about the band itself. ‘So fucked I can’t believe it,’ croaked Mascis. ‘If there’s a way I wish we’d see it/How could it work just can’t conceive it/Oh what a mess it’s just to leave it.’ Despite the internal strains, Freak Scene struck a chord with music fans looking for something different. Mainstream radio wouldn’t touch it, its success was fostered by word of mouth, a burgeoning underground fan base, and airplay on what few indie stations there were. It spent three months in the alternative rock chart.

Freak Scene heralded a perceptible cultural shift. Barlow had already noted the Dinosaur Jr. influence on British bands like My Bloody Valentine, while Nirvana took the band’s slacker aesthetic to the mainstream. The most overt example of its influence, according to Barlow, arrived in 1992. “Paul Kolderie and Sean Slade did Radiohead’s Creep after we’d done Bug,” says the bassist. “I remember hearing that and thinking they’ve picked up something from the Dinosaur Jr. session.”

Barlow was long gone by then. Just months after Bug’s release, Mascis and Murph told him the band had split. The next the bassist heard, they were touring Australia with his replacement. Barlow poured his scorn into his new project, Sebadoh. Songs like The Freed Pig were thinly veiled attacks on Mascis. Barlow has admitted to resorting to “small-minded” revenge tactics: “I sued J, wrote songs about him, shit-talked him any opportunity I got.”

After Mascis put Dinosaur Jr. on ice in 1997, the original trio eventually put aside past issues and re-formed in 2005 and performed Bug live in its entirety. “The whole act of playing the record over again on stage really redeemed it for me,” says Barlow. “I suddenly thought: ‘Fuck, it’s a great record! I get it! Now I know why people love it.’”