"I was never a show off!" - Tony Banks in The Prog Interview

Prog sat down with Genesis keyboard player Tony Banks upon the release of his classical album Five to discuss his shift into classical music and his career in general

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

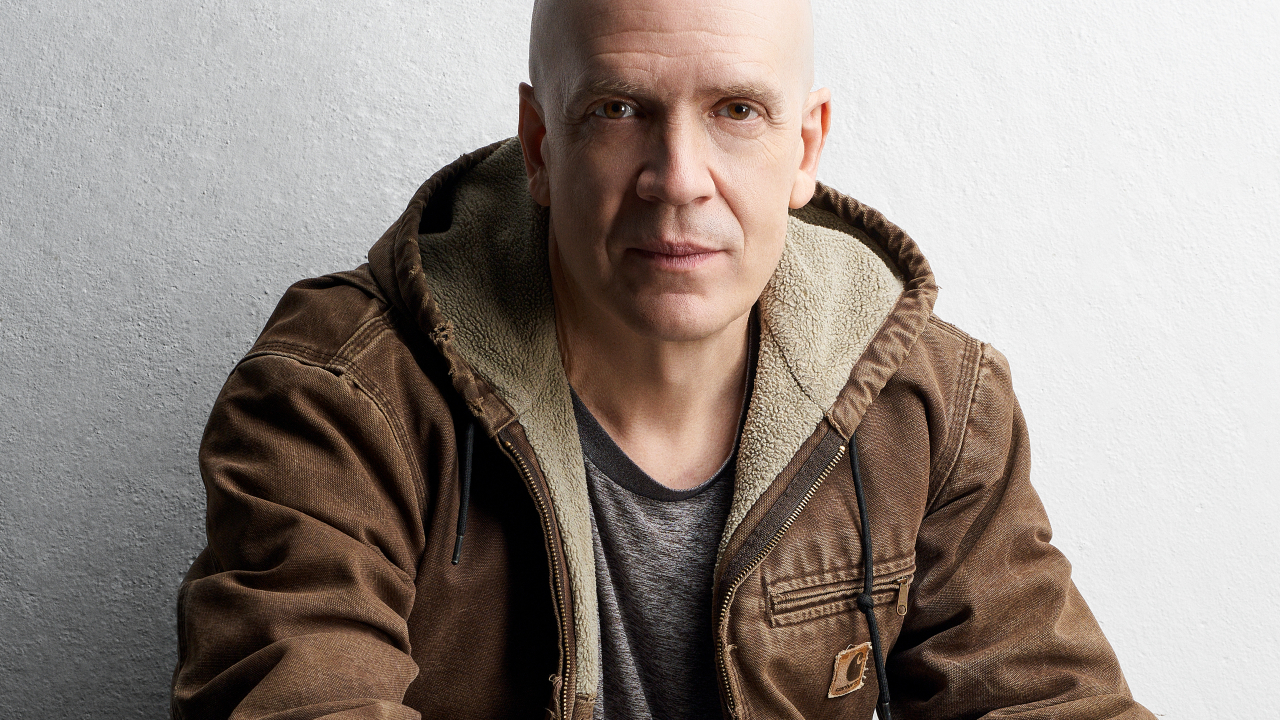

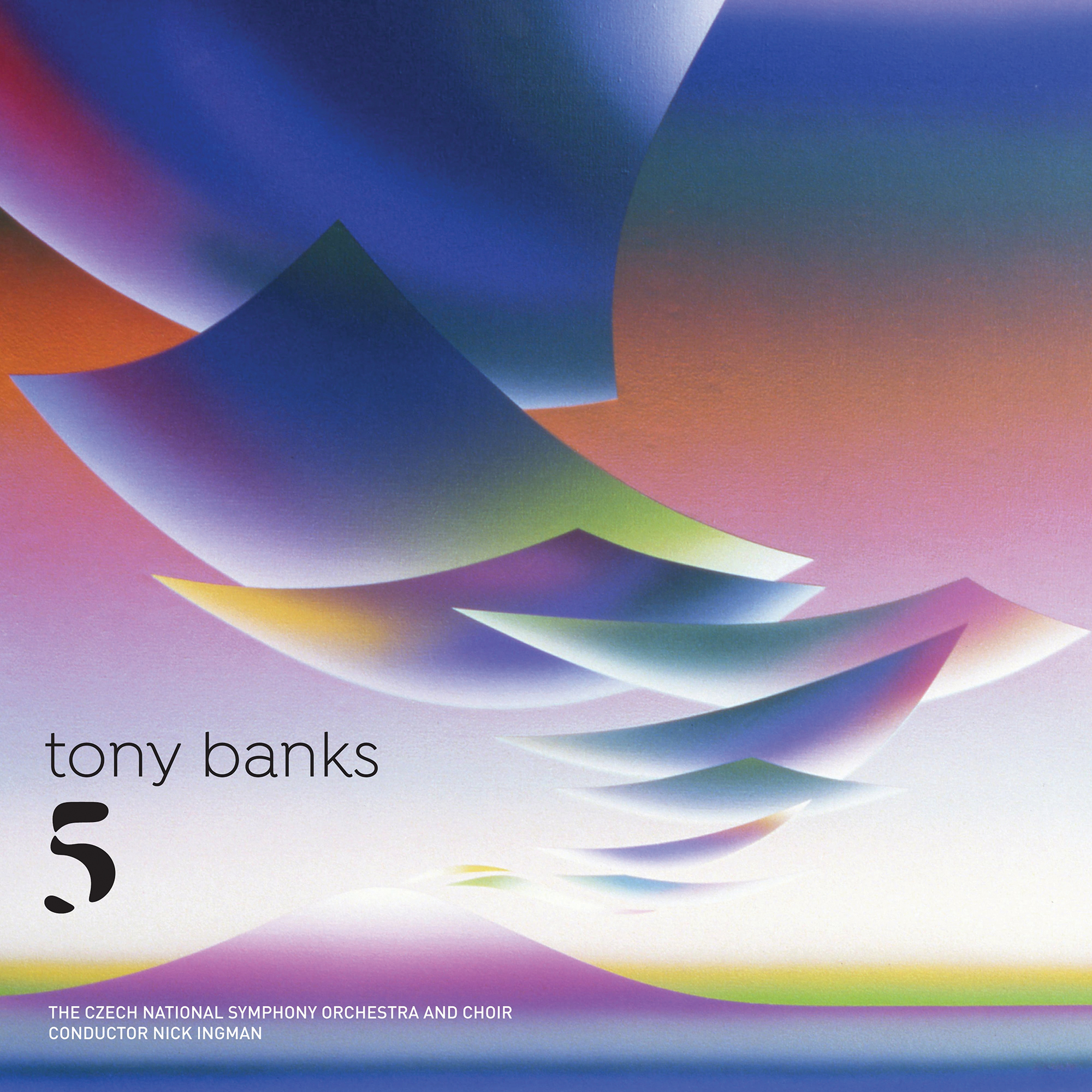

Tony Banks arrives at the swish, futuristic London members’ club carrying a free newspaper in one hand and dressed in black. He’s a youthful 67 (68 this month) and, belying any reputation for quintessentially English reserve, happily talks 19 to the dozen. He’s pleased, too, to lay eyes on a CD of his new orchestral album Five for the first time, though we spend a moment pining for the grander artwork of vinyl releases. Five – a set of (count ’em) five grandiose symphonic compositions – is both a long way from Genesis and yet, in its essence, a kindred swell of beauty and pathos.

Banks was, of course, key to (and keyboardist with) Genesis since their formation in 1967. From Charterhouse to revelation, from theatrical and experimental prog to a sharper focus and massive global success, from Supper’s Ready to Invisible Touch, he was always there, vital as a writer and player, the king of chords and key changes.

He may not have had the high profile of the band’s frontmen, but he’s been a sort of éminence grise, the power behind the throne. As Phil Collins has said, “Ever tried making Tony do something he doesn’t want to? Won’t happen.”

Article continues belowBanks reckons that by not being recognised in the street, being able to travel by Tube unbothered despite being a Rock’n’Roll Hall Of Famer, he has the best of both worlds.

While on his previous album, Six Pieces For Orchestra, he composed but didn’t play, he’s very much playing on this one.

“I am, but people shouldn’t get too excited,” he smiles. “The piano isn’t dominant, as such. My parts are a continuum, holding the thing together. But, you know, there’s no Firth Of Fifth here. That’s not the intention. It’s orchestral music.”

Prog finds out more…

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

When you were first discovering music, what were your first loves? Rock’n’roll or Ravel?

Well, the first thing I was ever aware of was show tunes, which my mother played at home – early Rodgers & Hammerstein stuff. And I heard a lot of hymns at school. Then my brother had a few records and I got into pop music. We both loved a version of Sixteen Tons by Frankie Laine. It’s not even the best-known version of that song, but I just played it to death, going: “This is fantastic!”

Then I listened to Pick Of The Pops with Alan Freeman. It was 1961, I was 11 years old. I heard a chart where The Young Ones by Cliff Richard was No.1 and I loved everything – Acker Bilk’s Stranger On The Shore, Bobby Darin’s Multiplication, Elvis’ Rock-A-Hula Baby. I had no discrimination at all, thought it was all wonderful!

The first record I bought was The Wanderer by Dion. Of course, it’s an incredibly simple 12-bar blues, but done with a great sound, great effects. I was hooked from then on – a complete fanatic for music from about 11 to 17. But then I got more discriminatory as time went by, and found more and more things I didn’t like…

Ah, the passing of innocence!

Yes, but then that early era of the groups in England – Beatles, Kinks, Animals, Stones – was so exciting. From the background I had, it was never something that ever seemed a possibility. When we were at school we dreamed of being this thing. Because I could play by ear, I loved working out Beatles songs from the radio. I started to understand the structures, and the idea of writing our own songs emerged with Peter [Gabriel], one of my closest friends. We started trying weirder chords, seeing what worked.

Ten years later, by the mid‑70s, whereas I’d liked everything when younger, I disliked most things, felt I’d heard it all before. Once you’ve heard the pattern of The Wanderer a dozen times, it gets a little dull. So you start looking to do different things.

And once we were a group, we were quite competitive with the groups we’d come in with – Family, Pink Floyd, King Crimson. A lot of bands had guitarists who’d just go nuts for ages, and I’d think, “Yeah, I’ve heard that now.”

You’ve done orchestral albums called Seven, then Six, and now Five. Are you getting closer to achieving your exact aims?

The first one was a learning process. The second one was more involved. With this one, I decided to go about it slightly more like I used to do solo albums and some Genesis stuff, where you put down a framework first. I did the piano and a lot of orchestration at home, so the structure, the template, was there. The original piano part stays in. I could control the tempos while letting it breathe. On the other ones, some pieces came out like I’d intended, others not quite. This is closer to how I envisaged it.

The first seeds for the album were sewn in Cheltenham…

Yes, the opening piece of Five, now called Prelude To A Million Years – unpretentiously, of course – was started for the Cheltenham Music Festival in 2014. It was quite traumatic for me to hear the orchestra playing it. It worked, but there’s always compromises. So here, working with the experienced Nick Ingham, we made what I’d written make sense for the full orchestra. We recorded the parts separately, more like the mechanics of a band. So I’m happy – if I fail, it’s on my own terms.

Five does have that distinctive Banksean, melancholy feel…

Hmm… wistful, nostalgic, perhaps, rather than melancholy. I’ve always been a nostalgic person. Lyrics like Fading Lights for Genesis were all about looking back on life, how things could have been different. But the attitude is usually one of ‘it all worked out in the end’. There’s a shape to this album, with Prelude, then Reveille, an awakening, then Ebb And Flow moving forward to Autumn Sonata, towards the end of life, and finally Renaissance, my favourite, which is a kind of rebirth, both an end and a beginning. That one moves from moody to optimistic – it could have been worked into a prog piece, I suppose!

Didn’t you initially write some of it during the Genesis years?

Oh, I know that’s been said, but just the first minute or so was written when I was trying to get into film music, so… the late 90s. I was listening to an old tape, a mix of strange drone and sweet melody, and I thought, “I can go somewhere with this.”

Yes, if you wanted to, you could do it with drums and vocals and stuff, but… I just love the expansiveness of an orchestra. Not that I’ve ever felt particularly constrained, but in a pop song you’re almost obliged to repeat things: choruses, middle eights. And I’ve always been happiest just sort of… rambling on.

So this genre is more in tune with your natural proclivities?

In a way, yes. I mean, I love writing songs too. Poets used to love writing sonnets as well as epics, you know? I’m very proud of some of the songs I’ve been involved in. In the old days, when we did something like Supper’s Ready or The Musical Box, we’d go on and on, but if repeating a phrase, we’d do a totally different arrangement of it. Supper’s Ready is the prime example, where the final section is a reprise of an earlier part but done a lot better to really give you that… feel.

There was always method in the madness. Non-fans seem to think early Genesis waffled on randomly, but it was all about the carefully built structure.

It’s a funny old thing, isn’t it? I had to be really cajoled into doing a solo, the first time. I was eventually persuaded to do one on Stagnation on Trespass – it was quite a thing for me! I got this first phrase which worked, then pretty much played scales and arpeggios for the rest of it! Anyway, then I had a clue. And okay, it became a part of Genesis, but we always wanted a freedom, a fluidity. Some of the bands we were compared to – ELP, Yes at times – would have a solo just because Keith [Emerson] or Steve [Howe] was a good musician. We never did that. Probably because neither Steve [Hackett] nor I wanted to be out front.

I know there are long keyboard sections like on The Cinema Show, but they had a purpose. And on Supper’s Ready, things grow from lighter to heavier until you get to the real climax, with the ‘666’ section. Some of your readers may know that piece! You get this massive, dramatic C chord, then Peter starts singing over the top. Initially I didn’t want him spoiling my chords [laughs] but then I realised how good it was.

That’s how you work as a group sometimes – you’re fighting against each other but the combination of those impulses produces something special.

Was it more of a boon or a traffic jam that all your personnel were highly talented individuals?

No one was carried: everyone was involved. The combination all round was interesting. But in a way that’s why the five-piece had to become a four-piece, then a three-piece – just too many ideas in there. Three of us was okay, because we covered all the bases. And fortunately we had a fantastic drummer who could sing! It was a good unit, that. I loved all the periods of Genesis really.

I once asked you why people don’t often make music like Supper’s Ready any more, and you said people weren’t allowed to. Can you elaborate on what you meant by that?

In the late 70s, there was a reaction against groups like us, which in a way was fair enough. The other thing is these pieces never get played. Back in ’72 or ’73, on Capitol Radio, Stairway To Heaven was voted best song of all time and number two was… Supper’s Ready. Now Stairway To Heaven is on the radio all the time, but Supper’s Ready? It’s simply too long! People’s attention spans, especially now with Spotify and the rest, are three or four minutes tops.

The current pop formula works, sells billions, but it must be so boring to write. Half the fun of constructing a song, for me, is moving away from the theme and then coming back to it again in an exciting way. Masters like Holland-Dozier-Holland and Burt Bacharach could do that. Take it away, then bring it back better. I love that, in all forms of music.

One of your finest compositions that goes (comparatively) under the radar is Mad Man Moon from A Trick Of The Tail…

Some get less attention than others. Of course, we never played it live, so there’s that. It’s more, dare I say, a feminine track. Melancholy. I was very pleased when I wrote it, especially the verses. The noodling in the middle is quite fun, but if you listen carefully, it’s beyond my playing ability! As for the line ‘A muddy pitch in Newcastle’, I’ve had a few phrases that you really shouldn’t. ‘Bread bin’ in All In A Mouse’s Night. ‘Double glazing’ in Domino. You either like those lines sticking out or you don’t. Anyway, Genesis have always been a rather divisive band, at least our more extreme ends. And I’ve always been happy with that.

Across the band’s lifespan, you evolved from songs based on fables and Bible stories to lyrics addressing real relationships and the modern world. Is it fair to say we hear you all, for better or worse, growing up in public?

That’s absolutely true. I mean, we came out of Charterhouse public school incredibly repressed and naïve. Whatever the opposite of streetwise is, we were it. We didn’t have the courage to write ‘I love you baby’ at all. So we went towards Ovid and Greek myths, Narcissus and the rest, and used that. Up to A Trick Of The Tail, we – bar the odd song – stayed out of reality. Even on The Lamb Lies Down On Broadway, it was still dressed up as fantasy.

It wasn’t until confidence came and we were feeling more at home with life that I wrote a genuine ‘love gone wrong’ song, which was Many Too Many. At the same time, Mike [Rutherford] wrote Follow You Follow Me. There was less hiding behind myths and legends; we could move in a more straightforward direction.

And that new direction won you a whole new audience?

I’d say it doubled our audience! A lot of females had found us… fairly impenetrable. The Fountain Of Salmacis: what the hell was that all about? But we now pulled in people to like the other stuff as well. At our shows we’d do old and new. Although, at that last tour in 2007, we’d do long instrumentals like Duke’s Travels and half the audience would go for a loo break. Then the next song was Hold On My Heart, and the other half would go. I like it all; I’d have stayed put for all of it!

We’d have done more UK shows on that tour, but we had a funny idea of what our status was. A lot of the cognoscenti don’t like us – they never got over the fact that we survived 1977, and we were Public Enemy No.1 at that time. So we’ve always had a strange image here. But the way it went, we felt we could’ve done more and it would’ve been nice. But it wasn’t to be. And it probably was the last one.

Really? So there’ll be no more Genesis gigs, ever?

I mean, poor Phil, he’s not going to be able to drum again. He can sing, but… we’ll see.

Have you been to any of his solo concerts?

Yes. They’re going pretty well, I think, after a slightly shaky start. I saw him at the Albert Hall before he had a fall and had to cancel a couple. It was okay: it wasn’t brilliant. Great musicians, effects and lights. He was singing fine, very warmly. It’s just… you wanted him to be leaping around doing the tambourine dance, y’know? Can’t do that any more, I’m afraid.

Have you seen Steve Hackett’s Genesis Revisited shows?

I haven’t, no. Haven’t seen him live for years actually. It’s great that they’re playing those songs though. There is an irony to it, in that Steve’s the one playing this stuff and he left the band! But I heard their version of Afterglow on the radio: that sounded good.

Genesis fans will never agree on the best album, or even the best era. Is that a help or a hindrance?

I remember when Abacab came out, we had about eight albums in the Top 100. People went back and discovered the earlier ones, which is great. But we don’t sell much these days. We never had that definitive album the way Floyd had The Dark Side Of The Moon or the Eagles had Hotel California. Again, we’re… divisive. We haven’t got that universality of somebody like Queen, who everybody likes to some degree. We were considered too fey to be street cred, so some like us, some don’t.

You played four nights at Wembley Stadium in 1987, though, which was a record back then. Was that a fun experience?

Very unusually for us and outdoor events, the weather was good. Those big shows aren’t the greatest musically, but they are a celebration. You get into the spirit with the audience. I remember coming off after the last show, thinking, “Oh well, there’s no way we’re ever going to be this big again! We’ve peaked.” That said, we sustained reasonably well with We Can’t Dance. It was an extraordinary time. We’d begun by playing noodly, obscure music with no image, not even changing to go onstage, and here we were. Sometimes I’d make myself look at it as an outsider, a spectator, and I enjoyed that.

I was never a natural performer, never a show-off, but I found a way of coping. If I did what I can do, which is play, I was always confident the others would make it work.

Is it fair to say you didn’t think the 2014 Together And Apart documentary worked?

We were disappointed with that. Mike and I saw it about a week before it came out, and it was… terrible. So we quickly got a new director and recut it, and it was better, but things were in there that shouldn’t have been. We’d done better documentaries in the past, like 2008’s Come Rain Or Shine, which shows the hilarious minutiae. But we didn’t feel good about this one.

With the solo careers, originally it only focused on Phil and Peter. Mike and I managed to get us in, but of course we didn’t get Steve in, which was a mistake. We did try. But overall the thing didn’t do its job. There were some witty things said, and it was nice to have us all in a room together again. And when everyone pointed out that I shouted the loudest to get my own way, I took it as a compliment – it suggests I’m more responsible for the music!

How did you feel about Genesis being analysed by serial killer turned music critic Patrick Bateman in the controversial novel American Psycho?

Well… it was strange, but interesting. That character’s not very likeable, to put it mildly, but he loves Genesis and contrasts our old and new music in detail. So it was oddly flattering, but in a backhanded way. Hey, getting mentioned at all is nice!

As the recipient of 2015’s Prog God award, you got more than mentioned…

Yes, fantastic! I was surprised. I’ve always stayed in the background to some extent, so am never quite sure if people are aware of how much I do. And with Peter presenting it, it gave us a chance to make jokes about each other. We have a good relationship. Obviously we don’t see each other like we used to, but when we do, we go back to that close friendship we had very quickly.

So what’s next for you? After Five, will you go forth to Four?

Oh, I do this because I love to, and because I can afford to on the back of what I’ve done in the past. It isn’t a commercial proposition, really. Maybe it’s an ego trip, which is fine. When my earlier solo albums did nothing, it was like beating myself up. But Six got to No.1 in the classical charts, and there’s interest from more than just loyal Genesis collectors. So that’s great. And once Five is out, I’ll no doubt feel cravings again…

This article originally appeared in issue 85 of Prog Magazine.

Chris Roberts has written about music, films, and art for innumerable outlets. His new book The Velvet Underground is out April 4. He has also published books on Lou Reed, Elton John, the Gothic arts, Talk Talk, Kate Moss, Scarlett Johansson, Abba, Tom Jones and others. Among his interviewees over the years have been David Bowie, Iggy Pop, Patti Smith, Debbie Harry, Bryan Ferry, Al Green, Tom Waits & Lou Reed. Born in North Wales, he lives in London.