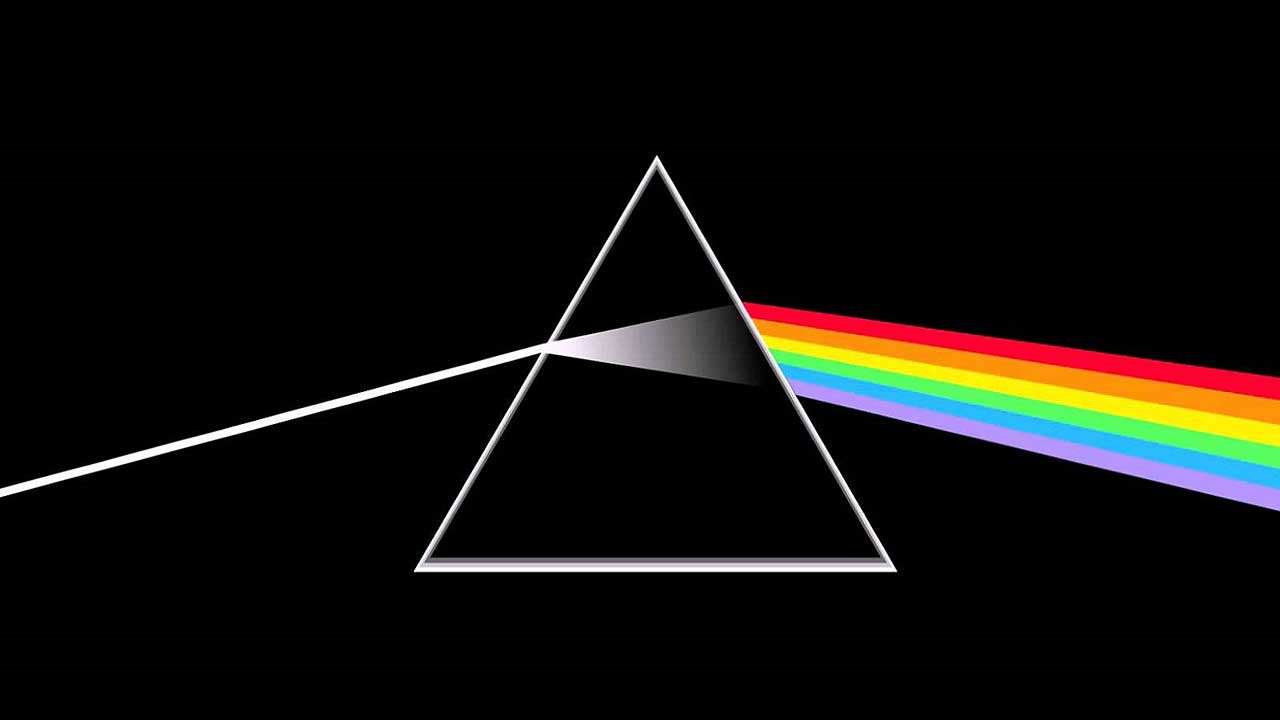

The Dark Side Of The Moon by Pink Floyd: the ultimate track-by-track guide

A look at the musical intricacies of Pink Floyd's masterpiece The Dark Side Of The Moon

Pink Floyd's The Dark Side Of The Moon is an unusual album in may respects, not least in that it's an avowedly uncommercial album with a huge commercial legacy. This wasn't Michael Jackson's Thriller, and album powered to enormous success off the back of multiple hit singles. Nor was it Fleetwood Mac's Rumours, an album of effervescent, deathless anthems that sound as fresh today as they did in the summer of 1977. It certainly wasn't a rock juggernaut like Bat Out Of Hell or Back In Black.

Nope. The Dark Side Of The Moon was, and is, weird. It's bold but introverted, tuneful but challenging, filled with clever twists and unexpected turns. It featured just two singles (Money and Us And Them), and while neither was a hit, both are undeniable classics.

Below we reveal the secrets of The Dark Side Of The Moon's 10 tracks.

Speak To Me

The creeping introduction of the pounding heartbeat was lifted from the band’s contribution to the Zabriskie Point soundtrack in 1970. Fading in from a deep, resonant heartbeat, it seems to suggest a baby’s first bleary impressions of the brash, cynical world.

Credited to Nick Mason, although written by Roger Waters, the title came from the album’s engineer Alan Parsons’ oft-repeated instruction from the studio control booth. It also featured a vari-speeded clock lifted from Time, a scream from The Great Gig In The Sky and spoken parts: “I’ve been mad for fucking years” from road manager Chris Adamson, and “I’ve always been mad” from Abbey Road doorman Gerry O'Driscoll. And then…

Breathe In The Air

The languorous chord progression of Breathe In The Air finally bursts out of a crescendo of screams and backwards sounds. Two of David Gilmour’s long-term fascinations are on here: the Leslie rotating speaker on the rhythm guitar, and the gently swooping pedal steel (although Roger Waters has claimed that this is an open-tuned Stratocaster played with a slide).

The song is about trying to be true to yourself, constructed during the Broadhurst Gardens sessions in London by Waters, Gilmour and Rick Wright. Gilmour’s vocals are double-tracked for fuller effect.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

On The Run

Emerging from one of the album’s many smooth cross-fades, On The Run is built largely with sounds from the EMS VCS3 synth. The ‘train’ sound is feedback from Gilmour, then a number of sound effects were added, along with the vox pops that Waters had recorded.

The ‘Travel Section’ is a VCS3-based assembly with footsteps added by Parsons, and words from Floyd roadie Roger The Hat. Gilmour, backed up by Parsons, says he first managed to get notes from the synth, which Waters then replaced; Waters says that it was he who first elicited meaningful sound from it.

Time

Recorded during the first studio stint, on June 8, 1972. Parsons added the alarm clock sequence, which he had just recorded for a quadraphonic sound demo. The heartbeat is Mason’s bass drum. Gilmour’s guitar tone is biting and spiky, creating a marked contrast between the A section and the smoother B section.

The track ends with a smooth reprise into Breathe. So smooth, in fact, that you can easily fail to notice the sudden switch to E-minor, where the B section in Time usually ends on E-major.

The Great Gig In The Sky

Gerry O'Driscoll and Floyd engineer Peter Watts give their thoughts on dying. The music was mostly laid down on June 25, 1972. Then on January 21, 1973, 25-year-old session vocalist Clare Torry supplied three hours of improvised vocals, replacing Bible readings and a Malcolm Muggeridge speech that had featured in the live version.

Torry was working as a staff songwriter for EMI. She was not a particular fan of Pink Floyd, and had other plans for the evening, including, she later admitted, tickets to see Chuck Berry, so a session was scheduled for the following Sunday. “I think they thought: ‘Well maybe we should have a vocal on it and we’ll see how it goes.’ So I listened to it and I thought to myself: ‘What the hell do I do?’ I had no idea. Somewhere in the back of my mind it crossed quickly that perhaps I should pretend that I was an instrument. I don’t really think they had any more idea than I had, It was just an experiment.”

The results were a hugely emotive wail that elevated the track to new heights. Torry recorded three versions, and the final version was assembled from those takes. The band members were so reserved in their response that she left the studio under the impression that her vocals would never make the cut. She became aware they were used only when she saw the album at a local record shop and spotted her name in the credits.

Money

Waters came up with the unusual 7/8 bass line in the studio at Broadhurst Gardens, and later added the cash-register effects after recording coins and money thrown into his wife’s industrial food mixer. The basic track was done on June 7, 1972, recording tremolo guitar, bass, drums and aWurlitzer electric piano through a wah-wah pedal, all at various speeds.

Gilmour’s old friend Dick Parry plays sax, which Gilmour follows with three distinctly different guitar solos over a more standard 4/4 backing, thus creating perhaps the prime example of his ability to play screaming blues guitar. Released as a single in the US, it reached No.13, and at gigs people started screaming for ‘the hit’.

Us And Them

Richard Wright had recorded an earlier, instrumental version in 1970, which was submitted (but ultimately rejected) for Zabriskie Point. The Dark Side Of The Moon version was recorded on June 1, 1972, the band’s first day in the studio.

Gerry O'Driscoll, Mr and Mrs Pete Watts and Roger The Hat add spoken parts, the latter saying: “short, sharp, shock”. Wings guitarist Henry McCullogh memorably admits: “I don’t know, I was drunk at the time,” in response to the question: “Were you in the right to thump that person on New Year’s Eve?” The big star of the track is Dick Parry, whose sax solo is a lesson in subtle melodicism.

Any Colour You Like

This is the only track by Pink Floyd written by Gilmour, Mason and Wright without Waters. Yet again, the VCS3 is dominant, supported this time by Gilmour’s Univibe-enhanced guitar parts, one with more overdrive than the other and panned to opposite sides of the stereo spectrum.

The final title refers to Henry Ford’s Model T car claim: “You can have it any colour you like, so long as it’s black.” Gilmour claims to have lifted his guitar sound from Eric Clapton’s Leslie speaker sound on Cream’s Badge.

Brain Damage

The Lunatic Song, to give it its early title, was written by Waters about Syd Barrett and Cambridge. The opening lines were taken from a song Waters wrote for Meddle called – appropriately enough – The Dark Side Of The Moon but was never recorded.

The ‘grass’ is the square in between the River Cam and King’s College Chapel. Once again, Gilmour’s guitar is through a Leslie rotating speaker, over a backing of a VCS3, the recurring heartbeat and full band. Jerry Driscoll talks about being mad, Pete Watts laughs, Waters sings.

Eclipse

Another track with a Waters vocal (with Gilmour harmonising), which he wrote specifically to ‘end’ the album. Comprising his standard ‘list’ lyric formats, it is intended to leave listeners in an upbeat mood. Jerry Driscoll states: “There is no dark side of the moon. As a matter of fact, it’s all dark.” (His further observation that “The thing that makes it look alight is the sun” was not used.)

The heartbeat closes the album, just as it introduced it. The previous track, including Gilmour’s steady, even arpeggio playing, segues into Eclipse, but with the repeating chord progression (D, D/C, Bb, A) adding a mantra-like quality that perfectly complements the uplifting lyrics of this album closer. Notice how Gilmour’s double-tracked Leslie guitar doesn’t stick to the same chord shapes throughout, moving instead to higher inversions, so the guitar doesn’t get lost among Rick Wright’s huge, swirling organ chords.

As the last chord fades to reveal the heartbeat, which started the album, sit back and reflect – you’ve just listened to one of the finest albums in rock history. Now press ‘play’ again…

Hugh Fielder has been writing about music for 50 years. Actually 61 if you include the essay he wrote about the Rolling Stones in exchange for taking time off school to see them at the Ipswich Gaumont in 1964. He was news editor of Sounds magazine from 1975 to 1992 and editor of Tower Records Top magazine from 1992 to 2001. Since then he has been freelance. He has interviewed the great, the good and the not so good and written books about some of them. His favourite possession is a piece of columnar basalt he brought back from Iceland.

- Fraser LewryOnline Editor, Classic Rock