"Steve was living out this James Brown fantasy, only he'd taken it one step too far": Quarrels, cocaine, and the rise and fall of Humble Pie

In 1969 an exciting new supergroup was born - but the story of Humble Pie is one of frustration and crushing disappointment

It's 1972. Gathered in a suite in a plush Beverly Hills Hotel are lawyers, management, record company ‘suits’ and the four members of Humble Pie. While the contracts to be signed are being handed out in a clockwise direction, a plate upon which is piled a large mound of top-dollar cocaine is being passed the other way.

“All I can tell you,” says drummer Jerry Shirley, grimacing, “is that we were far more interested in the progress of the plate. That breaks every rule you’re taught as a youngster in the music business – do not sign high, always sign straight. So we only have ourselves to blame.”

If you thought the film Almost Famous, with its depiction of 70s music business excess, was more fiction than fact, then the Humble Pie story may just stop you in your tracks. Ironically, the movie’s musical consultant was Peter Frampton, who quit Humble Pie in 1971 at the height of their US fame, and made big headlines himself five years later.

But while Frampton became an icon of the time, Humble Pie have tended to be somewhat overlooked by the writers of rock’s history books. Only when singer Steve Marriott died in a 1991 house fire – started by his own cigarette – did the band’s name return to the front pages, and again last year with an all-star 10th-anniversary show. Even then, Marriott’s previous band the Small Faces was the name most often mentioned in the obituaries.

But the likes of the Quireboys, FM and Thunder have evoked echoes of the rambling, scrambling and often inspired Humble Pie sound. In the US – the Pie’s most successful market – Gov’t Mule have covered them, and Bonnie Raitt and Melissa Etheridge are devotees. And in a neat touch, Black Crowes singer Chris Robinson’s wife Kate Hudson played the female lead in Almost Famous.

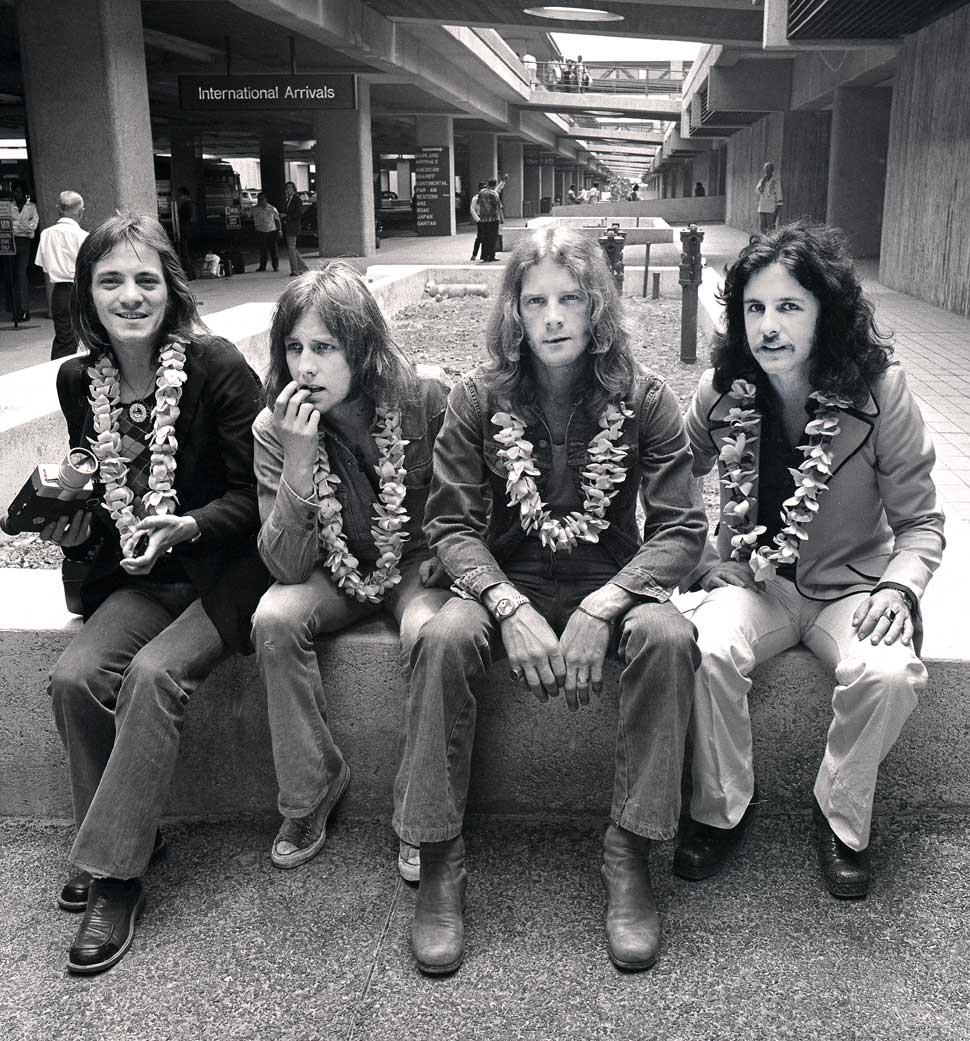

From the off, though, Humble Pie were to be a reluctant supergroup. Marriott and Frampton had stopped enjoying the teen adulation of their previous groups The Small Faces and The Herd respectively, and wanted above all to be considered serious musicians.

“We wanted to build it slowly,” drummer Jerry Shirley recalls. “And that was partly why the band’s name was chosen. It worked against us, because it took three or four years before we actually made the record everybody expected of us.”

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Frampton revelled in the freedom:“The first day we got together, in Jerry Shirley’s mother’s living room, I think, we were doing songs off [The Band’s] Music From Big Pink. We were just having a lot of fun playing. And I think both Steve and I realised that we could do anything we wanted, now we were starting all over again. It wasn’t that good for Humble Pie’s long-term direction, because we did everything – acoustic, country, you name it we did it, all the way up to full-on rock’n’roll."

The story of the band’s formation has been mis-told a thousand times. Rather than Marriott muscling in on Frampton’s band, it was the latter who wanted to be one of The Small Faces.

Frampton: “Glyn Johns called me up and said: ‘The Small Faces are going to go to France to do this record with [French rock star] Johnny Halliday. He’s always been a big fan and wants to do a couple of Ronnie Lane/Steve Marriott songs’.

“The way he put it was: ‘Johnny would like either Eric Clapton or Jimmy Page, but they’re busy. Can you come?. So we went to Paris and I joined The Small Faces for a week. Which was a dream come true.

“I flew back with Glyn and went to his house straight from the airport, as he wanted me to listen to a new band he’d just recorded. After hearing the first side of Led Zeppelin my jaw was on the floor. Then the phone rang, and it was Steve: ‘Look, man, I just left The Small Faces. Can I join your band?’.”

That band, Humble Pie, ended up on Immediate Records, where the combination of a creative band with songs coming out of their ears and a record company desperate for cash resulted in two albums that have since been released a dozen times.

“When you consider we were only in the studio between the months of April and July [1969] intermittently, a week here, a week there, it was a tremendous amount of input for a relatively short space of time,” Jerry Shirley says.

Singles didn’t figure in the equation initially, but Natural Born Bugie nevertheless went to No.1 in several European countries (No.4 in the UK). “Steve had a bad feeling about singles,” Shirley says, “because he associated them with screaming little divs, as opposed to serious music fans. Which is what he and the whole band were trying to appeal to – people who were into music.”

So off-the-cuff was Natural Born Bugie that it didn’t even get on to the band’s second album, Town And Country, which arrived in the record stores in December 1969, just six months after Pie’s debut, As Safe As Yesterday Is. Although those first two albums had been recorded by a band with no live experience together, Humble Pie were soon to get to know every inch of America’s freeways and turnpikes, thanks to their management.

“They’d done it before with Joe Cocker,” Shirley says. “Put the band out there, have them play for months, years, whatever, until they’re tighter than a duck’s ass, then capture that on vinyl and away you go.”

But the talent-packed Pie initially proved too eclectic for American rock audiences to digest. And although they would play an ‘unplugged’ opening set – way ahead of its time – it was clear they would have to cut the fiddly bits and concentrate on the down-the-line blues rock that ended the show.

“By our third record [Humble Pie],” Frampton explains, “our first album for A&M in 1970, Glyn Johns said: ‘I think you ought to look at your direction. If you pay attention to your strengths, we might have something. Steve’s the singer, Pete’s the lead guitarist, Greg’s the bass player and Jerry’s the drummer – how’s that?’

“We all sang a little bit, but we relinquished the singing to Steve. No one had a problem with this because it was such an honour to be in a band with someone who had a voice like that. I hate the term ‘legendary’, but there’s only one Steve, and we were all lucky to be in a band with him.”

In 1971 Humble Pie exploded into major stardom with not one but two best-sellers. Studio album Rock On progressed things in the right direction, with Marriott singing R&B over heavy riffs the others came up with. The tour to promote that record also resulted in Performance: Rockin’ The Fillmore, one of the hottest live albums of the period.

The live album was full of classic blues and soul songs rocked up and rolled out, Pie style. “Our philosophy,” Frampton recalls, “was that if you’re going to do someone else’s song, make it your own and add something to it – otherwise leave it alone.”

The best examples were Ray Charles’s I Don’t Need No Doctor and the New Orleans voodoo classic Walk On Gilded Splinters. Shirley and Frampton later came across the latter’s writer, Dr John, in New York at a record company function and were warmly embraced. Frampton: “He said: ‘I just love you guys. And you know why? Cos I was in jail when you did that song of mine. With the money I got from that I hired myself a much better lawyer and got out quick. You guys got me out of jail!‘.”

But just as major stardom was beginning for Humble Pie, Frampton broke out of what he saw as his own, creative, ‘prison’ to go solo. “At one point, my songs were okay for Humble Pie,” he says, “but now they weren’t, and that’s what made my mind up. Steve was an incredible teacher. I learnt so much from him. But it was almost a Mick and Keith love/hate thing between us. Leaving was a very difficult decision, but we thought …Fillmore was going to be our biggest record, and I figured that if I didn’t get out now I’d be sucked in and it would be harder.”

Marriott’s excessive drug intake was also causing problems between the two frontmen. Frampton was uneasy with such habits; though he confesses he himself “caught up later”. The split was at the time blamed on musical differences, the inference being that Frampton was somehow holding the band back from playing the heavy music that brought them most success. Frampton, however, says: “The feeling when I read that was, what bullshit. Pie were still successful. In fact the most successful record of all was the next one, ‘Smokin’’. I’m not on it, but it’s still my favourite because I was a fan of the band.”

The parting of the ways was a sticky one, but Jerry Shirley doesn’t think Marriott held a grudge: “Steve, being the ‘rough around the edges’ type of guy he was, thought Peter’s material could have been a bit tougher, but that was just personal opinion. What a lot of people don’t know is how highly he rated him as a guitar player. He felt that Peter had been wrongly promoted as a prettyace, and one of the main things he tried to achieve was to get him recognised as a truly great guitar player. So, no, I don’t think there was resentment.

“Steve put on a big show of bravado – ‘Oh well, Peter can go off and do his lightweight girl’s blouse stuff’ – but he didn’t really mean any of it. He was really hurt, and very scared about what was to come because he would have to be even more the frontman. But fortunately we found Clem [Dave Clempson, guitarist] fairly quickly, and it did enable us to maintain a tough rhythm and blues-type band, certainly for the first two years, so again that worked out okay.”

As Shirley explains, Dave ‘Clem’ Clempson of jazz rockers Colosseum, had rung for an audition – and was hired before he arrived: “Steve had pretended not to be Steve, I’m not sure why, and told him to call back. Meanwhile, he got someone to get Colosseum Live, played it, and found this solo he liked. When Clem called back, Steve asked him down to what he thought must be a audition. When he got there all the press was there. He’d already joined the band and didn’t even know it!” A bit of a risk? “Typical Steve.”

But Marriott’s world was falling apart at the seams. The one true love of his life, first wife Jenny, left him in the middle of Pie’s success. As a result there was a part of him that resented the band’s success because he saw that as the reason his marriage broke up.

“It wasn’t the success itself, but how he handled it,” Shirley reflects. “I believe Steve was never the same after he and Jenny broke up. He married again a couple of times, and I’m sure he loved the women he got with, but there was something very, very special about Steve and Jenny’s relationship. It permeated everything. And when he was writing songs, as a result they were the greatest he ever wrote – think about All Or Nothing and Afterglow.”

Marriott’s long, drawn-out marriage break-up started in the latter part of 72 and went on to the beginning of 74. “You can put that next to a map of our music and literally see the deterioration,” Shirley continues. “The band should have stopped and allowed them to have their own space for a while, allow him to clean up his act a bit and so on, but of course that never happened; it was always, ‘There’s another tour, there’s another album, blah blah…’.. He couldn’t cope.”

But along with the lows there were also the highs that helped to compensate, notably dates with Grand Funk Railroad that included Shea Stadium in New York and Hyde Park in London. At Shea Stadium, in front of 60,000 people, Pie blew Grand Funk away in front of their own, very partisan audience. Equal to that was seeing Marriott control an audience in a theatre to the point where he could have the band come down in volume, then throw the microphone away while singing and have those people at the back of the hall still hear every word.

Another time, they supported Alice Cooper in his own backyard of Pittsburgh baseball stadium, also in front of 60,000 people. “We were on the bill as special guests,” Shirley recalls, “and tore the place apart. We came off and were in the dressing room, minding our own business, when there was a knock on the door and in comes Alice. He leans against the wall very nonchalantly and says: ‘How the fuck do you expect me to follow that?’.”

The lows included a night in St Louis when Marriott took a couple of unidentified pills, followed them with a couple of downers, and eventually fell into the drum kit. “To be fair to him, considering he was ‘on 10’ all the time, he only did that on fewer than a handful of occasions,” says a still-loyal Shirley. “And even at his worst Steve was still better than most of his competition at their best.”

The combination of cocaine and drink was gradually taking the edge off the music, and Marriott handled it worse than the rest of the band. “He would go on five- or six-day benders where he wouldn’t even think of sleeping,” the drummer reveals. “He would proudly call himself ‘five-day Marriott’, when in actual fact he was dying inside. It was his way of handling what happened to his personal life.”

The crunch came with 1973’s Eat It, the album everyone thought would build on the No.6 US success of Smokin’ and propel Humble Pie into stadium rock’s superleague. But, bulked up with live and also substandard material, it flattered to deceive and was, Shirley believes, “the worst we ever made. We didn’t keep our eye on the ball. And no one stopped and said: ‘This album isn’t good enough. Go and do it again’. Then we might have stood a chance.”

The original band’s last two albums, Thunderbox (1974) and Street Rats (1975), were improvements in terms of sound quality, but again they reflected a poor choice of material. “The only song from Thunderbox that got lasting recognition was a cover of I Can’t Stand The Rain, which [original singer] Anne Peebles loved. I was very proud of that. But on stage it had become like a soul revue… Steve was living out this James Brown fantasy, only he’d taken it one step too far.”

A backing vocal trio, the Blackberries – Clydie King, Billie Barnum and Vanetta Fields – played to this, but it polarised fans. The quartet had started to quarrel internally. And when the time came to record the next album the record company put their foot down and insisted on an outside producer. Amazingly, the choice was one-time Immediate boss Andrew Oldham.

“Steve knew that Andrew was somebody he was able to get his own way with. And Andrew, bless his heart, tried very hard to get some semblance of a decent record out of us. But we were getting on so badly at the time that we were recording our parts individually. Steve would come in, do his stuff and leave; we would come in, do our stuff and leave. It was just ridiculous. And it showed, because the record sunk.”

For old boy Peter Frampton, meanwhile, megastardom was just around the corner in the shape of his live album, Frampton Comes Alive.

After Humble Pie split in 1975, Marriott made a solo album that flopped, leaving him at a loose end. But the re-release of The Small Faces’ Itchycoo Park and its Top 10 chart success late that year saw his former band asked to perform on Top Of The Pops.

“They got back together for that one-off and they had a great amount of fun,” Shirley says. “But before they knew it big business was in the air. They were offered record deals, except that Steve was not contractually free to do it. That’s the point he gave up his rights [on Humble Pie] to move forward with The Small Faces. Unfortunately for Steve that was giving up quite a lot, and I don’t even know if at the time he knew what he was doing. He just wanted out.”

It was the latest of several financial disasters for Marriott. Immediate had gone bust in 1970, and for the next 25 years no royalties were paid to Marriott or any of his Small Faces/Pie colleagues for the recordings they’d made for the label.

Having fared badly in so many business deals and with The Small Faces reunion a brief affair, Marriott found it easier in his latter years to travel the country in a blues band, Packet Of Three, jamming a few 12-bars for beer money.

Shirley briefly joined the band in 1985-86, but failed to pull his colleague out of the rut. “I tried really hard to get him motivated, but he just wasn’t interested. Looking back I realise I shouldn’t have bothered, because he was happy. He just wanted to play Jimmy Reed tunes all night. And why not?”

Steve Parsons, alias singer Snips of the band Sharks, now works in the world of film and TV music and produced Marriott’s last album, 1989’s 30 Seconds To Midnight. He reveals: “I got to be very good friends with Steve in the years before he died, and I wouldn’t trade my experience for what he went through. All that Lear Jet, superstar, big old rock guy getting screwed by your managers, getting fucked up on drugs, et cetera. If you ask me if I’d rather have platinum records and that life or the one I’ve got, I’ll have the one I’ve got, thank you.”

A route out of the pub-rock circuit had opened for Marriott when a similarly aimless Peter Frampton re-entered his life at the beginning of the 90s.

“I’d got to a point in my career where there was not a lot of interest in me in America, England, anywhere,” Frampton says. “A record producer suggested I should get a band together, so I started auditioning. But I realised no one would fit, because I was looking for a Marriott. I called him up and asked if he thought we could write together. He said: ‘Fuck me, yeah. That would be good, wouldn’t it?’. So, to cut a long story short, just as America and her allies were gearing up for Desert Storm, we created our own storm.”

Frampton flew to England, where the two of them wrote one-and-a-half songs in their first session. “He was just as into it as I was, and decided he’d move to Santa Monica and give it a go. We’d agreed to do one album and a tour to promote it; we weren’t thinking any longer term than that. But Steve got cold feet…”

Drugs were still the sticking point, and Frampton felt his old frustrations welling again: “For me, work is fun but recreation is for weekends… It was very disappointing. I guess Steve didn’t like the fact that I was the guy that didn’t – you know, I didn’t even smoke any more. We had record companies and publishing companies after us, but he just decided that was it, he wasn’t going to be a part of it. I figured I’d give him time to cool off and we’d come back to it, but he went home about ten days later. And we all know what happened the very day he got home.”

Jerry Shirley was in Cleveland, Ohio, at a friend’s apartment when he took the call that delivered the news. “It was devastating,” he remembers. “I honestly thought it was a dream. But, looking back, it was something that could have happened dozens of times. Steve was notorious for going to bed with his ashtray, cigarette and book on the bus; everybody used to walk backwards and forwards to check on his bunk to make sure he’d not passed out. If you saw him nodding off you’d take the cigarette and put it out for him.

“In a way,” Shirley continues, “I thought he was indestructible. Steve pushed it close to the edge, but because he’d survived so many close shaves I thought nothing could happen to him. There were several instances in his life with fire – he almost had a fixation for it. He claimed to have burned his school down as a young boy by putting a dog-end down a hole in the floorboards. It was a story he made up, and first told with The Small Faces. It made good print so he stuck with it. I only found out years later from his mother that it actually didn’t happen.”

There have been two attempts at getting Humble Pie back on the menu, one with Marriott and one without. The first, in 1979-81, resulted in two albums, On To Victory and Go For The Throat, while earlier this year saw the release of Back On Track which, as the review in Classic Rock put it, showed enough promise to suggest that “Pie Y2K could some day produce an outstanding rock album that would add to the legend”.

The Steve Marriott Memorial Concert at London’s Astoria in 2001 was the first time Peter Frampton and his successor in Humble Pie, Clem Clempson, had played together. And Frampton enjoyed being on stage with Shirley and bassist Greg Ridley again after three long decades.

“I don’t think I stopped smiling the whole night,” he says. “It was just like 30 years had disappeared. We missed Steve – obviously it wasn’t the same and never could be – but all the same it was great for us to get back together again. I think everybody got the same rush out of it, and if we ever get the chance to get back together again we still want to do some sort of tribute record to Steve.”

Should that project come off, names in the frame include Paul Rodgers, whose current Bad Company line-up includes sometime Pie guitarist Dave ‘Bucket’ Colwell, and Rod Stewart. But that’s in the future.

So how to sum up a band who got so close to, yet remained so far from, the highest musical echelon in those hazy days of sex, drugs and rock’n’roll? For Peter Frampton, Humble Pie were simply “the best band I was ever in!”.

Jerry Shirley believes that “the band had potential to be one of the true greats, but did not achieve anywhere close to what they could have done, other than on stage. We sold ourselves short, sadly. It would have been nice to have achieved the potential the band had, but we had a lot of fun along the way.”

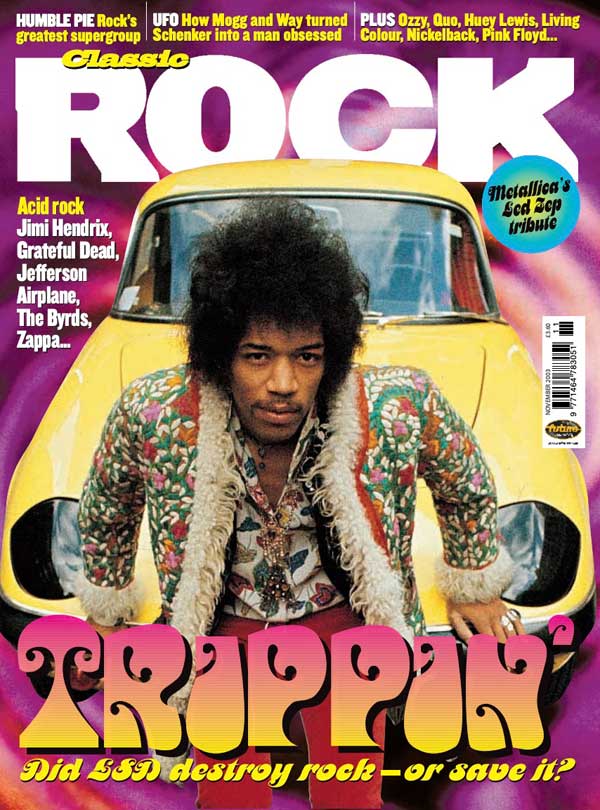

This feature originally appeared in Classic Rock issue 59 (November 2003)

Michael Heatley is the author or editor of over thirty biographies, including Bon Jovi: In Their Own Words, The Complete Deep Purple and Dave Grohl: Nothing to Lose. Since 1977 he has written more than a hundred music, sport and TV books.