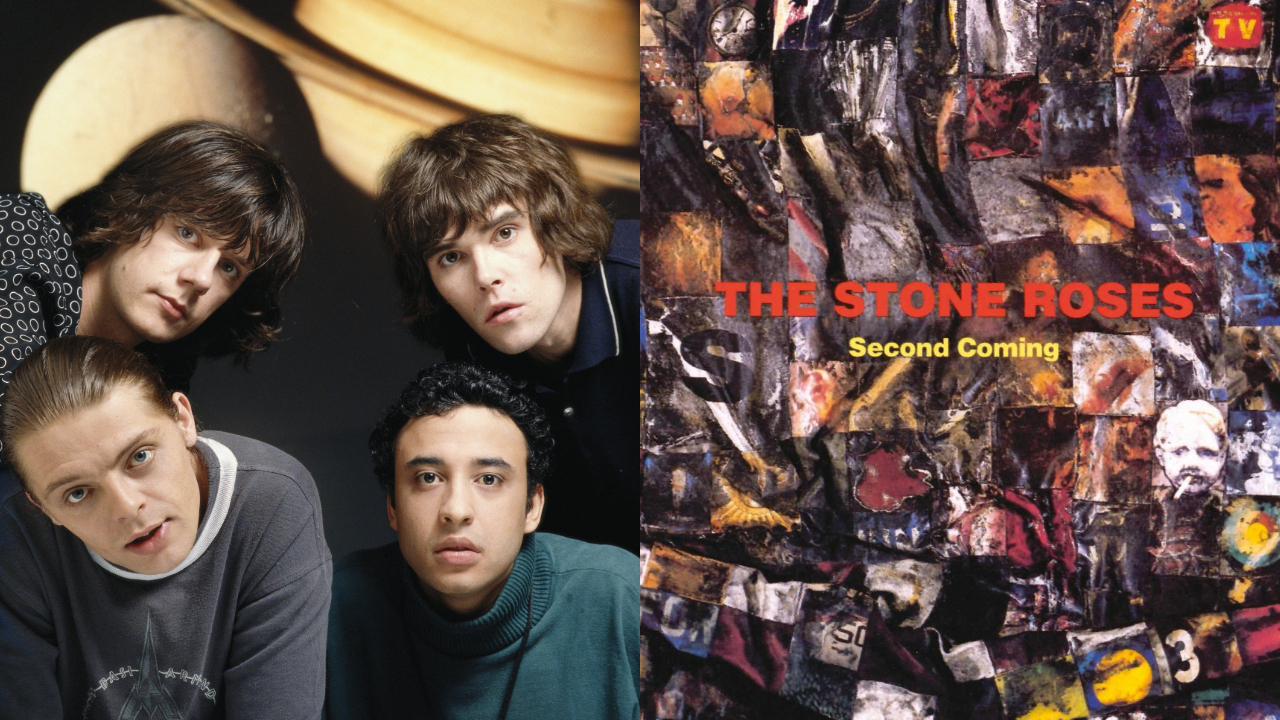

"The hype was so great that we were never going to be able to fulfil it." The "nightmare" birth of the Stones Roses' wildly-expensive and long-delayed second album Second Coming, by those who were there, and those who quit

After The Stones Roses set the British music scene alight with their stunning debut album, the expectation was that they would take over the world with album two. Things didn't quite go to plan

Three weeks into The Stone Roses' 1993 recording session at Rockfield Studios in Monmouth, Wales, the band's producer John Leckie placed a phone call to their American A&R man Gary Gersh to express some concern. Using the legendary studio where Queen recorded Bohemian Rhapsody, Rush recorded A Farewell To Kings, and more recently Sepultura had recorded Chaos A.D. was costing Geffen Records £800 a day, and Leckie felt duty-bound to tell Gersh that the Manchester band had recorded precisely nothing.

Gersh, the executive who had signed both Sonic Youth and Nirvana to Geffen, took the news in his stride,

"He said, 'No problem, just let them be creative, don’t worry about the budget'," Leckie said in a recent interview with MOJO magazine.

"The programmer hired to do loops for £400 a day was just sitting there. They had the best drummer in the world, and they wanted to use drum machines! It was a nightmare."

Leckie had actually begun work on the work on the follow-up to The Stones Roses' widely-acclaimed self-titled 1989 debut album on January 30, 1990. And while the quartet, vocalist Ian Brown, guitarist John Squire, bassist Gary ‘Mani’ Mounfield and drummer Alan 'Reni' Wren, had undeniably been creative in the intervening years - during their 1991 stay at Bluestone rehearsal studios in Pembrokeshire, Wales arty guitarist Squire had created an eight-foot “snow penis” - they just hadn't recorded much in the way of actual music. In fact, only two songs, July 1990 single One Love and its B-side Something's Burning, had been completed.

To be fair, for a significant part of this time, the band were subject to a legal injunction preventing them from recording new material, while their lawyers sought to extricate them from their contract with Silvertone Records, a case they eventually won in the summer of '91, before signing to Geffen, with a two million pound advance for the making of their second record. They then took the rest of the year off.

At the beginning of the summer of 1993, John Leckie oversaw sessions with the band at another studio, Square One, in Bury, a facility the band had been using one and off for six months. For the producer, the sessions were a waste of time.

“That period was a disaster,” he told MOJO in 2001. “Apart from the lack of air conditioning, by the time we got to the studio, it would be 10 or 11 o’clock at night. They were recording as a band by now, but it didn’t come to anything. There were always problems: power cuts, electrical things, people disappearing.

“Eventually I said, For fuck’s sake, let’s get up at 11 o’clock in the morning, or lunchtime. Let’s try and get here by four. They’d say, ‘Oh yeah, we’ll do that tomorrow, definitely: we’ll have an early night, get up at 12, have a good lunch'... And then it’d be three, four, five o’clock, and lan would come and say [blearily], ‘What’s happening?’ You can’t change people."

"It was hard to get the momentum kicked in for a while," Mani admitted to Vox magazine in 1995.

"And after such a whacking delay, we thought, Why rush it?" John Squire added. "We were going to be criticised anyway."

The latest news, features and interviews direct to your inbox, from the global home of alternative music.

When sessions switched to Rockfield, Leckie lasted three months before bailing out, utterly exasperated, with only fragments of songs completed. "Reni would go home for days," he told MOJO, "or John wouldn't come out of his room. Or they'd endlessly play the same thing over and over." Leckie's replacement, Paul Schroeder, would quit too, in February 1994. At which point Rockfield's in-house engineer, Simon Dawson, took over. And finally, finally, the group began to turn the corner.

"We wanted it to sound more live and real, and we tried throughout the making of the record to preserve as much of the band's live sound and feel as possible," Dawson told Sound On Sound in 1995. "You very quickly realise with these guys that they love playing and jamming."

Preceded by the excellent, driving, Led Zeppelin-esque single Love Spreads, Second Coming finally emerged in the UK on December 5, 1994. The album sold over 100,000 copies in its first week on sale, but only charted at number 4, being out-sold by The Beatles Live At The BBC, among others. Geffen, however, were bullish about its potential in America, where its release was set for January 16, 1995.

"This is a great English band," Geffen executive Tom Zutant, the man who signed Guns N' Roses to the label, told Vox. "They have the potential to put English rock and roll back on the map. If I was a UK journalist I would feel proud about a British band reclaiming the throne. It's been American music for years, and British music has been in the fucking toilet."

It's fair to say that The Stone Roses did not "reclaim the throne" in America with Second Coming. The album peaked at number 47 on the Billboard chart: it probably didn't help that Rolling Stone awarded the record just two stars, bemoaning its "tuneless retro-psychedelic grooves". Though it would go on to sell one million copies worldwide, boosted by brilliant singles Ten Storey Love Song and Begging You, this was significantly less than anyone had anticipated.

“The hype was so great that we were never going to be able to fulfil it,” Mani told MOJO. “Everyone wanted Electric Ladyland and Sgt Pepper rolled into one.”

The band, however, were confident that album three would be the one, with Ian Brown boldly telling Vox that the aim was to make "the best LP of all time" next time out.

The Stone Roses wouldn't make a third album.

A music writer since 1993, formerly Editor of Kerrang! and Planet Rock magazine (RIP), Paul Brannigan is a Contributing Editor to Louder. Having previously written books on Lemmy, Dave Grohl (the Sunday Times best-seller This Is A Call) and Metallica (Birth School Metallica Death, co-authored with Ian Winwood), his Eddie Van Halen biography (Eruption in the UK, Unchained in the US) emerged in 2021. He has written for Rolling Stone, Mojo and Q, hung out with Fugazi at Dischord House, flown on Ozzy Osbourne's private jet, played Angus Young's Gibson SG, and interviewed everyone from Aerosmith and Beastie Boys to Young Gods and ZZ Top. Born in the North of Ireland, Brannigan lives in North London and supports The Arsenal.